Breeze BJS 2017 Becomingin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Conference 2017.Indd

SCOTTISH GREENS AUTUMN CONFERENCE 2017 CONFERENCE LEADING THE CHANGE 21-22 October 2017 Contents 3. Welcome to Edinburgh 24. Sunday timetable 4. Welcome to Conference 26. Running order: Sunday 5. Guest speakers 28. Sunday events listings 6. How Conference works 32. Exhibitor information 10. Running order: Saturday 36. Venue maps 12. Child protection 40. Get involved! 13. Saturday events listings 41. Conference song 22. Saturday timetable 42. Exhibitor information Welcome to Edinburgh! I am pleased to be able to welcome you to the beautiful City of Edinburgh for the Scottish Green Party Autumn Conference. It’s been a challenging and busy year: firstly the very successful Local Council Elections, and then the snap General Election to test us even further. A big thank you to everyone involved. And congratulations – we have made record gains across the country electing more councillors than ever before! It is wonderful to see that Green Party policies have resonated with so many people across Scotland. We now have an opportunity to effect real change at a local level and make a tangible difference to people’s lives. At our annual conference we are able to further develop and shape our policies and debate the important questions that form our Green Party message. On behalf of the Edinburgh Greens, welcome to the Edinburgh Conference. Evelyn Weston, Co-convenor Edinburgh Greens 3 Welcome to our 2017 Autumn Conference! Welcome! We had a lot to celebrate at last year’s conference, with our best Holyrood election in more than a decade. This year we’ve gone even further, with the best council election in our party’s history. -

Talking 'Fracking': a Consultation on Unconventional Oil And

Talking "Fracking": A Consultation on Unconventional Oil and Gas Analysis of Responses October 2017 BUSINESS AND ENERGY social research Talking ‘Fracking’: A consultation on unconventional oil and gas. Analysis of responses Dawn Griesbach, Jennifer Waterton and Alison Platts Griesbach & Associates October 2017 Table of contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction and background ........................................................................... 4 Policy context 4 The Talking ‘Fracking’ consultation 4 About the analysis 5 2. About the respondents and responses ........................................................... 7 How responses were received 7 Number of responses included in the analysis 9 About the respondents (substantive responses only) 10 Responses to individual questions 11 3. Overview of responses ................................................................................... 13 Views on fracking and an unconventional oil and gas industry 13 Pattern of views across consultation questions 14 4. Social, community and health impacts (Q1) ................................................. 15 Health and wellbeing 16 Jobs and the local economy 17 Traffic, noise and light pollution 18 Housing and property 18 Quality of life and local amenity 18 Community resilience and cohesion 19 5. Community benefit schemes (Q2) .................................................................. 20 Criticisms of and reservations about community -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

Recruited by Referendum: Party Membership in the SNP and Scottish Greens

Recruited by Referendum: Party membership in the SNP and Scottish Greens Lynn Bennie, University of Aberdeen ([email protected]) James Mitchell, University of Edinburgh ([email protected]) Rob Johns, University of Essex ([email protected]) Work in progress – please do not cite Paper prepared for the 66th Annual International Conference of the Political Science Association, Brighton, UK, 21-23 March 2016 1 Introduction This paper has a number of objectives. First, it documents the dramatic rise in membership of the Scottish National Party (SNP) and Scottish Green Party (SGP) following the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. The pace and scale of these developments is exceptional in the context of international trends in party membership. Secondly, the paper examines possible explanations for these events, including the movement dynamics of pre and post referendum politics. In doing so, the paper outlines the objectives of a new ESRC- funded study of the SNP and Scottish Greens, exploring the changing nature of membership in these parties following the referendum.1 A key part of the study will be a survey of SNP and SGP members in the spring of 2016 and we are keen to hear views of academic colleagues on questionnaire design, especially those working on studies of other parties’ members. The paper concludes by considering some of the implications of the membership surges for the parties and their internal organisations. The decline of party membership Party membership across much of the Western world has been in decline for decades (Dalton 2004, 2014; Whiteley 2011; van Biezen et al. -

A Breakdown of Common Acronyms and Terms Used in the Scottish

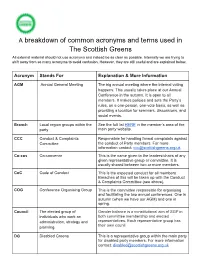

A breakdown of common acronyms and terms used in The Scottish Greens All external material should not use acronyms and instead be as clear as possible. Internally we are trying to shift away from so many acronyms to avoid confusion. However, they are still useful and are explained below. Acronym Stands For Explanation & More Information AGM Annual General Meeting The big annual meeting where the internal voting happens. This usually takes place at our Annual Conference in the autumn. It is open to all members. It makes policies and sets the Party’s rules, on a one-person, one-vote basis, as well as providing a location for seminars, discussions, and social events. Branch Local region groups within the See the full list HERE in the member’s area of the party main party website. CCC Conduct & Complaints Responsible for handling formal complaints against Committee the conduct of Party members. For more information contact: [email protected] Co-cos Co-convenor This is the name given to the leaders/chairs of any given representative group or committee. It is usually shared between two or more members. CoC Code of Conduct This is the expected conduct for all members. Breaches of this will be taken up with the Conduct & Complaints Committee (see above). COG Conference Organising Group This is the committee responsible for organising and facilitating the two annual conferences. One in autumn (when we have our AGM) and one in spring. Council The elected group of Gender balance is a constitutional aim of SGP in individuals who work on both committee membership and elected administration, strategy and representatives. -

Greens Oppose Environment of Catholic Schools in Scotland

Fr Colin ACN reacts to Pro-life activists MacInnes unanimous ISIS stand up in reports from genocide Edinburgh and quake in recognition by Glasgow. Ecuador. Page 7 MPs. Page 3 Pages 4-5 No 5669 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday April 29 2016 | £1 Greens oppose environment of Catholic schools in Scotland I Controversial stance omitted from 2016 Scottish Green Party manifesto but still remains party policy By Ian Dunn and Daniel Harkins what the thinking behind that policy is. last year, the group said that ‘our posi- Catholic education in Scotland out of education in Scotland. It doesn’t seem to be about tolerating tion stated in [a] 2013 report has not their manifesto for the 2016 elections. “I am very supportive of state-funded THE Scottish Green Party has other people’s wishes, or allowing changed from the belief that sectarian- Mr McGrath suggested the hostile Catholic schools,” Ms Sturgeon told the admitted that it remains intent on parental choices, but instead imposing ism would not be eradicated by closing response the party received in 2007 to SCO last year. “They perform ending state-funded Catholic edu- a one size fits all system contrary to all schools.’ its education policy may have moti- very well.” cation in Scotland. developments in education all over Another Green candidate, David vated members to leave it out of their Ms Davidson has also told the SCO Despite the policy being left out of the world.” Officer, who is on the Scottish Green manifesto this time. -

Minutes, 29Th Council, European Green Party

29th Council, European Green Party 23-25 November 2018, Berlin, Germany Venue Telekom Hauptstadrepräsentanz Französische Strasse 31a-c Adopted Minutes Friday, 23 November 2018 Welcome Words 13:00 – 13:30 Speakers: • Monica Frassoni: Co-chair of the EGP • Antje Kapek: Co-chair of the Green Group in the Berlin state parliament • Annalena Baerbock: Co-chair of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Germany Monica Frassoni welcomes the participants to the 29th EGP Council in Berlin. She starts by informing the participants that the two Turkish Greens co-leaders, Eylem Tuncaelli and Naci Sönmez, had their passports confiscated by the Turkish authorities and were not allowed to travel to Berlin. She then salutes the newly elected Green party leaders. She states that this Council officially starts the Greens common European electoral campaign, and that for the first time Greens can be game changers in shaping Europe’s future. She claims that the recent successes of the “Green wave”, which includes electoral and civil rights victories, stem from the fact that Greens have a European character and are seen as an alternative to both status quo mainstream parties and nationalist forces. Monica Frassoni calls for the Greens to transform the Green wave into more votes and garner support for their policies even across party lines, in a moment when the fight against climate change is visibly lagging behind. She also argues that Europe is not a doomed project and stresses the role that Greens have in this battle as the most cohesive pro-European parties. Monica Frassoni warns that Green policies for an ecological transition must be perceived as rooted in solidarity and equity, if they are to be widely supported. -

Friday 20 March

Green Party Spring Conference, 20-22 March 2020 Hilton Metropole Brighton Friday 20 March Time Room Session/Event 11.00-18.00 Registration desk open 12.00-13.15 Workshop: A1 SOC Workshop: B1 Food and Agriculture Voting Paper Workshop: A3 DRC – A2 PDC Meeting: Land Use Policy Working Group Meeting: Climate Emergency Policy Working Group 13.30-14.00 Main Hall (Oxford suite) WELCOME TO CONFERENCE and CO-LEADER SPEECH 14.15-15.30 Main Hall (Oxford suite) Panel: Rising to the challenge: can capitalism be green? Fringe: Introduction to plenaries for first timers Workshop: A5 GPRC – A4 Transition Team Workshop: A6 Climate Emergency Policy Working Group Training: Election agents – how to make your role simple Meeting: Food and Agriculture Policy Working Group Meeting: LGBTIQA+ Greens 15.45-18.30 Main Hall (Oxford suite) 15.45-15.55 GREENS OF COLOUR SPEECH followed by 15.55-18.30 OPENING PLENARY - Section A (SOC and other Reports); Emergency Motion 18.45-20.00 Main Hall (Oxford suite) Fringe: The Big Surveillance Capitalism Scandal Fringe: Before we tax meat - exactly what is a healthy diet? Fringe: What happened in Bristol West 2019 Training: Moving from climate emergency to climate action planning in your Council and community Workshop: D3 Diversity of media representation (18.45-19.20) D4 Diversity in Target Seats (19.20-20.00) Meeting: Migration, Refugees and Asylum Policy Working Group Meeting: Green Party Women Evening Wagner Hall £5 veggie and vegan curries made just for us by the Real Junk Food Catering (see map) Project. 18.00-21.00, Bar open until 22.30 1 Green Party Spring Conference, 20-22 March 2020 Hilton Metropole Brighton Evening Wagner Hall 20.00-22.00 Big Green Quiz night, £3 per team member. -

1 Response on Behalf of the Scottish Green Party General Comments The

Response on behalf of the Scottish Green Party General comments The Scottish Green Party (SGP) welcomes the publication of this draft energy strategy. We welcome, in particular, the whole system approach, reference to other policy areas, and consideration of current practice, and short, medium and longer term targets. We are pleased to take this opportunity to respond to this consultation, and are glad other organisations and individuals can also participate. The SGP would welcome similar discussions in other parts of the UK, and indeed, internationally. We very strongly welcome the Scottish Government’s commitment to honouring international agreements regarding climate change. We believe that Scotland, along with other industrialised nations, must take the lead in acting urgently to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate change. So we support a key aim of this draft strategy consultation: to work out how to decarbonise the energy sector, while providing for the nation’s needs. We welcome the draft strategy’s discussion of the whole energy system, and its inclusion both of matters which are both devolved to Holyrood and of those reserved to Westminster. We would hope for constructive cooperation between the two governments on these matters, and that any differences in priorities or strategies across administrations will not hamper the implementation of the bold and ambitious final strategy which we hope will arise from this consultation. Chapter 3: Energy supply Q1 What are your views on the priorities for the Scottish Government set out in Chapter 3 regarding energy supply? In answering please consider whether actions are both necessary and sufficient for delivering our vision Regarding the specific five priorities (section 66 of draft strategy) The SGP would want to see much higher prominence given to demand reduction, when discussing energy sources. -

Our Election Manifesto 2021 Our Common Future

Our election manifesto 2021 Our common future About us We are a political party called the Scottish Green Party. A political party is a group of people who share the same ideas about how a country should work. We think we are the best political party to run the Scottish government. Our manifesto tells you our plans for how we would make Scotland a better and fairer place for everyone. We call this Our Common Future. We hope you like our plans and vote for us in the election on Thursday 6 May 2021. 2 What is happening now The weather around the world is changing. It is called climate change. Because of climate change we have: • More floods • Heatwaves • Animals dying out 3 Climate change is caused by pollution. Pollution mostly comes from burning things like coal, gas and oil. We burn coal, gas and oil to: • Make electricity • Heat our homes • Drive cars 4 WeW need to stop polluting the world. If we don’t, the climate will get worse aand life will get harder for lots of ppeople. In Scotland the government does not have the powers it needs to: Help stop climate change • Build a fairer and greener society • for everyone Green means doing things in a way that does not harm the climate. 5 Here are our ideas about what we would do to change this. Infrastructure Infrastructure are some of the things we need to make the country work. Things like roads, railways, electricity and gas supplies. We will make sure the way we run our infrastructure also looks after our climate. -

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Edited by Chris Kostov Logos Verlag Berlin λογος Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de . Book cover art: c Adobe Stock: Silvio c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH 2020 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-3-8325-5192-6 The electronic version of this book is freely available under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence, thanks to the support of Schiller University, Madrid. Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH Georg-Knorr-Str. 4, Gebäude 10 D-12681 Berlin - Germany Tel.: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 92 https://www.logos-verlag.com Contents Editor's introduction7 Authors' Bios 11 1 The EU's MLG system as a catalyst for separatism: A case study on the Albanian and Hungarian minority groups 15 YILMAZ KAPLAN 2 A rolling stone gathers no moss: Evolution and current trends of Basque nationalism 39 ONINTZA ODRIOZOLA,IKER IRAOLA AND JULEN ZABALO 3 Separatism in Catalonia: Legal, political, and linguistic aspects 73 CHRIS KOSTOV,FERNANDO DE VICENTE DE LA CASA AND MARÍA DOLORES ROMERO LESMES 4 Faroese nationalism: To be and not to be a sovereign state, that is the question 105 HANS ANDRIAS SØLVARÁ 5 Divided Belgium: Flemish nationalism and the rise of pro-separatist politics 133 CATHERINE XHARDEZ 6 Nunatta Qitornai: A party analysis of the rhetoric and future of Greenlandic separatism 157 ELLEN A. -

Environmental Policy and Politics

This is a repository copy of Teachers’ Topic Guides : Environmental Policy and Politics. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/96287/ Version: Published Version Other: Tobin, Paul Alexander orcid.org/0000-0002-3024-8213 and Bomberg, Elizabeth (2015) Teachers’ Topic Guides : Environmental Policy and Politics. UNSPECIFIED. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ PSA Teachers’ Topic Guides Topic: environmental policy and politics - Professor Elizabeth Bomberg and Dr Paul Tobin Image: Steve CC BY-NC-ND A guide for politics teachers in sixth form colleges and schools 1 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND POLITICS (2015) By Professor Elizabeth Bomberg, Professor of Environmental Politics, University of Edinburgh; Dr Paul Tobin, Leverhulme Fellow in Environmental Politics, University of York Elizabeth is a keen teacher and researcher in the broad area of environmental politics and policy. Her geographic emphasis is on the UK, European Union and the US, and her thematic focus is on climate change, energy politics, activism, and multi-level governance.