Recruited by Referendum: Party Membership in the SNP and Scottish Greens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Conference 2017.Indd

SCOTTISH GREENS AUTUMN CONFERENCE 2017 CONFERENCE LEADING THE CHANGE 21-22 October 2017 Contents 3. Welcome to Edinburgh 24. Sunday timetable 4. Welcome to Conference 26. Running order: Sunday 5. Guest speakers 28. Sunday events listings 6. How Conference works 32. Exhibitor information 10. Running order: Saturday 36. Venue maps 12. Child protection 40. Get involved! 13. Saturday events listings 41. Conference song 22. Saturday timetable 42. Exhibitor information Welcome to Edinburgh! I am pleased to be able to welcome you to the beautiful City of Edinburgh for the Scottish Green Party Autumn Conference. It’s been a challenging and busy year: firstly the very successful Local Council Elections, and then the snap General Election to test us even further. A big thank you to everyone involved. And congratulations – we have made record gains across the country electing more councillors than ever before! It is wonderful to see that Green Party policies have resonated with so many people across Scotland. We now have an opportunity to effect real change at a local level and make a tangible difference to people’s lives. At our annual conference we are able to further develop and shape our policies and debate the important questions that form our Green Party message. On behalf of the Edinburgh Greens, welcome to the Edinburgh Conference. Evelyn Weston, Co-convenor Edinburgh Greens 3 Welcome to our 2017 Autumn Conference! Welcome! We had a lot to celebrate at last year’s conference, with our best Holyrood election in more than a decade. This year we’ve gone even further, with the best council election in our party’s history. -

Talking 'Fracking': a Consultation on Unconventional Oil And

Talking "Fracking": A Consultation on Unconventional Oil and Gas Analysis of Responses October 2017 BUSINESS AND ENERGY social research Talking ‘Fracking’: A consultation on unconventional oil and gas. Analysis of responses Dawn Griesbach, Jennifer Waterton and Alison Platts Griesbach & Associates October 2017 Table of contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction and background ........................................................................... 4 Policy context 4 The Talking ‘Fracking’ consultation 4 About the analysis 5 2. About the respondents and responses ........................................................... 7 How responses were received 7 Number of responses included in the analysis 9 About the respondents (substantive responses only) 10 Responses to individual questions 11 3. Overview of responses ................................................................................... 13 Views on fracking and an unconventional oil and gas industry 13 Pattern of views across consultation questions 14 4. Social, community and health impacts (Q1) ................................................. 15 Health and wellbeing 16 Jobs and the local economy 17 Traffic, noise and light pollution 18 Housing and property 18 Quality of life and local amenity 18 Community resilience and cohesion 19 5. Community benefit schemes (Q2) .................................................................. 20 Criticisms of and reservations about community -

Goldilocks and the Tiger

HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO Goldilocks and the Tiger: Conceptual Metaphors in British Parliamentary Debates on the British Exit from the European Union Marja Arpiainen Master’s Thesis English Philology Department of Languages University of Helsinki November 2018 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Marja Arpiainen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Goldilocks and the Tiger: Conceptual Metaphors in British Parliamentary Debates on the British Exit from the European Union Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Marraskuu 2018 92 s. + 5 liitettä (yht. 43 s.) Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielma keskittyy metaforien käyttöön Ison-Britannian parlamentissa maan EU-jäsenyydestä järjestetyn kansanäänestyksen kampanjoinnin aikana keväällä 2016. Tarkempana tutkimuskohteena on kampanjan molempien osapuolten, sekä EU-jäsenyyttä tukevan että eroa puoltavan, metaforinen kielenkäyttö. Sitä tarkastelemalla tutkimus pyrkii esittämään kampanjaryhmien mahdollisesti käyttämiä narratiiveja, jotka tukevat näiden ryhmien näkemyksiä Euroopan unionista sekä Ison-Britannian mahdollisesta erosta. Tavoitteena on myös pohtia yleisemmällä tasolla tämän tapauskohtaisen esimerkin kautta, kuinka vastakkaisia tavoitteita ajavat kampanjaryhmät hyödyntävät metaforia diskurssissaan. Tutkimus pohjaa Lakoffin ja Johnsonin vuonna -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

The Roots and Consequences of Euroskepticism: an Evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Political Science Publications Department of Political Science 4-2012 The roots and consequences of Euroskepticism: an evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party John B. Sutcliffe University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/poliscipub Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Sutcliffe, John B.. (2012). The roots and consequences of Euroskepticism: an evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party. Geopolitics, history and international relations, 4 (1), 107-127. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/poliscipub/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations Volume 4(1), 2012, pp. 107–127, ISSN 1948-9145 THE ROOTS AND CONSEQUENCES OF EUROSKEPTICISM: AN EVALUATION OF THE UNITED KINGDOM INDEPENDENCE PARTY JOHN B. SUTCLIFFE [email protected] University of Windsor ABSTRACT. This article examines the causes and consequences of Euroskepticism through a study of the United Kingdom Independence Party. Based on an analysis of UKIP’s election campaigns, policies and performance, the article examines the roots of UKIP and its, potential, consequences for the British political system. The article argues that UKIP provides an example of Euroskepticism as the “politics of oppo- sition.” The party remains at the fringes of the political system and its leadership is prepared to use misrepresentation and populist rhetoric in an attempt to secure sup- port. -

Brexit: Initial Reflections

Brexit: initial reflections ANAND MENON AND JOHN-PAUL SALTER* At around four-thirty on the morning of 24 June 2016, the media began to announce that the British people had voted to leave the European Union. As the final results came in, it emerged that the pro-Brexit campaign had garnered 51.9 per cent of the votes cast and prevailed by a margin of 1,269,501 votes. For the first time in its history, a member state had voted to quit the EU. The outcome of the referendum reflected the confluence of several long- term and more contingent factors. In part, it represented the culmination of a longstanding tension in British politics between, on the one hand, London’s relative effectiveness in shaping European integration to match its own prefer- ences and, on the other, political diffidence when it came to trumpeting such success. This paradox, in turn, resulted from longstanding intraparty divisions over Britain’s relationship with the EU, which have hamstrung such attempts as there have been to make a positive case for British EU membership. The media found it more worthwhile to pour a stream of anti-EU invective into the resulting vacuum rather than critically engage with the issue, let alone highlight the benefits of membership. Consequently, public opinion remained lukewarm at best, treated to a diet of more or less combative and Eurosceptic political rhetoric, much of which disguised a far different reality. The result was also a consequence of the referendum campaign itself. The strategy pursued by Prime Minister David Cameron—of adopting a critical stance towards the EU, promising a referendum, and ultimately campaigning for continued membership—failed. -

Electoral Revolutions : a Comparative Study of Rapid Changes in Voter Turnout

ELECTORAL REVOLUTIONS : A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF RAPID CHANGES IN VOTER TURNOUT by ALBERTO LIOY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Alberto Lioy Title: Electoral Revolutions: A Comparative Study of Rapid Changes in Voter Turnout This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Political Science by: Craig Kauffman Chairperson and Advisor Craig Parsons Core Member Erin Beck Core Member Aaron Gullickson Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School. Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2020. ii © 2020 Alberto Lioy iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Alberto Lioy Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science September 2020 Title: Electoral Revolutions: A Comparative Study of Rapid Changes in Voter Turnout In the political science scholarship on democratic elections, aggregate voter turnout is assumed to be stable, and depends upon an acquired habit across the electorate. Large turnout variations in a short period of time are therefore usually attributed to negligible contextual factors. This work establishes that such variations are more frequent than commonly thought and creates a novel theoretical framework and methodological approach for systematically studying rapid changes in voter turnout across Western Europe and Latin America. I attribute dramatic changes in voters’ participation, labeled electoral revolutions, to transformations in the party system competition and institutional credibility happening inside the national political context. -

Information Guide Euroscepticism

Information Guide Euroscepticism A guide to information sources on Euroscepticism, with hyperlinks to further sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 Brief Historical Overview................................................................................. 2 Euro Crisis 2008 ............................................................................................ 3 European Elections 2014 ................................................................................ 5 Euroscepticism in Europe ................................................................................ 8 Eurosceptic organisations ......................................................................... 10 Eurosceptic thinktanks ............................................................................. 10 Transnational Eurosceptic parties and political groups .................................. 11 Eurocritical media ................................................................................... 12 EU Reaction ................................................................................................. 13 Information sources in the ESO database ........................................................ 14 Further information sources on the internet ..................................................... 14 Copyright © 2016 Cardiff EDC. All rights reserved. 1 Cardiff EDC is part of the University Library -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

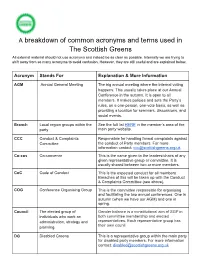

A Breakdown of Common Acronyms and Terms Used in the Scottish

A breakdown of common acronyms and terms used in The Scottish Greens All external material should not use acronyms and instead be as clear as possible. Internally we are trying to shift away from so many acronyms to avoid confusion. However, they are still useful and are explained below. Acronym Stands For Explanation & More Information AGM Annual General Meeting The big annual meeting where the internal voting happens. This usually takes place at our Annual Conference in the autumn. It is open to all members. It makes policies and sets the Party’s rules, on a one-person, one-vote basis, as well as providing a location for seminars, discussions, and social events. Branch Local region groups within the See the full list HERE in the member’s area of the party main party website. CCC Conduct & Complaints Responsible for handling formal complaints against Committee the conduct of Party members. For more information contact: [email protected] Co-cos Co-convenor This is the name given to the leaders/chairs of any given representative group or committee. It is usually shared between two or more members. CoC Code of Conduct This is the expected conduct for all members. Breaches of this will be taken up with the Conduct & Complaints Committee (see above). COG Conference Organising Group This is the committee responsible for organising and facilitating the two annual conferences. One in autumn (when we have our AGM) and one in spring. Council The elected group of Gender balance is a constitutional aim of SGP in individuals who work on both committee membership and elected administration, strategy and representatives. -

The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 the Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001

8 Philip Lynch The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 Philip Lynch As Conservatives reflected on the 1997 general election, they could agree that the issue of Britain’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a significant factor in their defeat. But they disagreed over how and why ‘Europe’ had contributed to the party’s demise. Euro-sceptics blamed John Major’s European policy. For Euro-sceptics, Major had accepted develop- ments in the European Union that ran counter to the Thatcherite defence of the nation state and promotion of the free market by signing the Maastricht Treaty. This opened a schism in the Conservative Party that Major exacer- bated by paying insufficient attention to the growth of Euro-sceptic sentiment. Membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) prolonged recession and undermined the party’s reputation for economic competence. Finally, Euro-sceptics argued that Major’s unwillingness to rule out British entry into the single currency for at least the next Parliament left the party unable to capitalise on the Euro-scepticism that prevailed in the electorate. Pro-Europeans and Major loyalists saw things differently. They believed that Major had acted in the national interest at Maastricht by signing a Treaty that allowed Britain to influence the development of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) without being bound to join it. Pro-Europeans noted that Thatcher had agreed to an equivalent, if not greater, loss of sovereignty by signing the Single European Act. They believed that much of the party could and should have united around Major’s ‘wait and see’ policy on EMU entry. -

Greens Oppose Environment of Catholic Schools in Scotland

Fr Colin ACN reacts to Pro-life activists MacInnes unanimous ISIS stand up in reports from genocide Edinburgh and quake in recognition by Glasgow. Ecuador. Page 7 MPs. Page 3 Pages 4-5 No 5669 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday April 29 2016 | £1 Greens oppose environment of Catholic schools in Scotland I Controversial stance omitted from 2016 Scottish Green Party manifesto but still remains party policy By Ian Dunn and Daniel Harkins what the thinking behind that policy is. last year, the group said that ‘our posi- Catholic education in Scotland out of education in Scotland. It doesn’t seem to be about tolerating tion stated in [a] 2013 report has not their manifesto for the 2016 elections. “I am very supportive of state-funded THE Scottish Green Party has other people’s wishes, or allowing changed from the belief that sectarian- Mr McGrath suggested the hostile Catholic schools,” Ms Sturgeon told the admitted that it remains intent on parental choices, but instead imposing ism would not be eradicated by closing response the party received in 2007 to SCO last year. “They perform ending state-funded Catholic edu- a one size fits all system contrary to all schools.’ its education policy may have moti- very well.” cation in Scotland. developments in education all over Another Green candidate, David vated members to leave it out of their Ms Davidson has also told the SCO Despite the policy being left out of the world.” Officer, who is on the Scottish Green manifesto this time.