Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manatee Springs State Park Three Day 'Springs Break' Real Florida

Manatee Springs State Park Three Day ‘Springs Break’ Real Florida Guide Note: Colored numbers correspond with numbers on the map and represent destinations for each day. Red = Day 1, Green = Day 2 and Blue = Day 3. Enjoy a three day ‘springs break’ sampling some of Florida’s crystal-clear watery gems sprinkled among the nine-county region known as the Nature Coast. You can make your base camp at Manatee Springs State Park’s full-service campground or the comfortable cabins at Fanning Springs State Park. Take your time sauntering from spring to spring, dip a paddle in the majestic Suwannee River, bike the scenic Nature Coast State Trail, and enjoy the natural wonders and wildlife of the region. Day 1 Manatee Springs State Park (1), with a full-facility campground surrounded by red oak woodlands, makes an excellent base camp for exploring the charms of the Nature Coast. The park’s first- magnitude spring produces an average of 100 million gallons of clear, cool water daily. In winter, West Indian manatees swim upriver to the warmer waters of the springs. Popular for snorkeling and scuba diving, the headwaters of the spring are also an inviting spot for swimming. Canoe and kayak rentals are available all year round on the spring run that forms a sparkling stream meandering through hardwood wetlands to the Suwannee River. Hiking and bicycling are available on eight miles of an inviting shady off-road trail system. Try your luck fishing from the park's boardwalk along the spring run and in the Suwannee River for largemouth bass, catfish and a variety of tasty pan-sized fish. -

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 House District

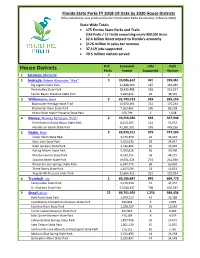

30, Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 House Districts This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 31,073,188 436 349,462 Big Lagoon State Park 10,336,536 145 110,254 Perdido Key State Park 17,191,206 241 198,276 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,545,446 50 40,932 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 26,651,285 416 362,492 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18,971,114 266 218,287 Blackwater River State Park 7,101,563 99 78,680 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578,608 51 65,525 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 41,626,278 583 469,477 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,558,966 106 83,636 Henderson Beach State Park 34,067,312 477 385,841 5 Drake, Brad 9 64,140,859 897 696,022 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 Deer Lake State Park 1,738,073 24 19,557 Eden Gardens State Park 3,235,182 45 36,128 Falling Waters State Park 5,510,029 77 58,866 Florida Caverns State Park 4,090,576 57 39,405 Grayton Beach State Park 17,072,108 239 186,686 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,911,495 97 78,277 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213,693 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 45,103,015 632 504,860 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 St. -

Renovations of Future County Offices Moving Along

CHIEFLAND Thursday, March 21, 2019 Proudly servingITIZEN Chiefland and Levy County for 69 years C2 sections, 22 pages Volume 70, Number 3 www.chieflandcitizen.com Chiefland, FL 32644 $.75 Chiefland resident Fire Chief: CPR devices will save lives SUZETTE COOK helps save lives, it also saves on injuries Reporter as well. “CPR causes a lot of injuries on wins millions the field,” he said. And even for trained Chiefland Fire Chief James Harris per- professionals under duress, Lall said on scratch-off formed CPR at the March 11 commission the device was made to be easy and will meeting to prove a point. continue to do compressions for one full hour on a battery and can be paused at Luis Bruno, 55, of “You have never heard me come up anytime for defibrillation. Chiefland, claimed a $5 here and ask to take money out of the - Harris felt so strongly about acquiring million top prize in the fire budget,” Harris said to the commis sion after demonstrating the efficiency an ARM for his department, he said, “I’ve $20 GOLD RUSH CLASSIC of an Automated Resuscitation Machine taken the time to look at this. This is ac- Scratch-Off game at Flor- tually another man that we don’t have.” ida Lottery Headquarters known as an ARM. The device costs $11,500. in Tallahassee. “This is the very first time,” he added. “I am asking permission for a lot of Bruno purchased his Harris, along with Michael Lall, vice money, I understand,” Harris said. “I winning ticket from president of AED Professionals medical think this is a piece of equipment we Murphy Express, located device company, acted out a scenario need to buy because of the manpower at 2126 North Young where a Harris started administering we have. -

Nature Coast State Trail Management Plan

APPENDIX B State Designation National Recreation Trail (NRT) Designation THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Appendix B-1 Appendix B-2 Appendix B-3 Appendix B-4 .Appendix A Designated State Parks Long Key 05 Monroe 763.24 147.95 Lease--- Trustees 09121/61 Pari< Open-Fee Required / /' State Pari< - Lower Wekiva River 03 Lake 17,137.55 588.02 Lease Trustees 08119176 Preserve Open-No Fee Required Preserve Stale Park Seminole' Madlra Bickel Mound 04" Manatee ., 5.68 4.32 Lease Trustees 04116148 Special Feature Site (A) Open-No Fee Required State Archaeological Site' Mike Roess Gold Head 02 Clay 2,059.67 115.47 lease Trustees 02115136 Park Open-Fee Required Branch State Pari< '''' ~ . '.' .''' . Mound Key ': • ,." . 04 lee 168.86 Lease Trustees 11/02161 Special Feature Site (A) Open-No Fee Required An:haeologicat State Pari< L',_ .... , Nature Coast Trail 02 Dixie 469.71 Lease: Trustees 12118196 Trail Open-No Fee Required State Park Gilchrist levy " '" .. ' North,Peninsula State Park 03 Volusla 519.90 "- 2.36 Lease Trustees 05116184 Recreation Area Open-No Fee Requ1ied alene 02 . A1achua .. ·__ . 1,714. 17 26.99 Lease Trustees 06129/36 ·.,Park Open-Fee Required State Park Columbia Ochlockonee River · .. 01 Wakulla. .'-370.33 15.13 Lease Trustees 05114170, Pari< Open-Fee Required State Park OletaRiver ._.,05 ..... Dade ... 1,012.64. 20.20 Lease Trustees 06109160 Recreation Ar.ea Open-Fee Required State Park Orman House ..... - ~ .. --,- 01 .. Franklin.' _'. " 1.SO Lease Trustees 02/02/01 Undetennined Open-Fee Requir~ Oscar Scherer 04 , 'Sarasota 1,376.96 4.66 Lease Trustees 09/12/56 Park Open-Fee Required State Park - .: ~ ;" Paynes Creek 04 Hardee 396.20 Lease Trustees 09/19n4 Special Feature Site (H) Open-Fee Required H"lStoric State Park ."."'(" .-.,--. -

30, House Districts

30, Florida State Parks FY 2018-19 Data by 2020 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, February 2020) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.6 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $176 million in sales tax revenue • 37,119 jobs supported • 29.5 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 35,086,662 491 399,461 Big Lagoon State Park 13,388,360 187 146,049 Perdido Key State Park 18,435,488 258 215,257 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,262,814 46 38,155 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,793,752 319 262,150 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,070,491 211 175,244 Blackwater River State Park 7,562,462 106 85,258 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 160,799 2 1,648 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 49,456,096 692 567,948 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 8,154,105 114 91,652 Henderson Beach State Park 41,301,991 578 476,296 5 Drake, Brad 9 69,939,012 979 747,560 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 Deer Lake State Park 2,102,533 29 24,057 Eden Gardens State Park 3,186,404 45 35,924 Falling Waters State Park 5,760,818 81 59,390 Florida Caverns State Park 4,532,155 63 44,215 Grayton Beach State Park 19,551,524 274 212,050 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,347,774 89 69,063 Three Rivers State Park 1,617,039 23 15,653 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 23,664,415 331 252,764 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 60,186,687 842 684,779 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 St. -

Avvlelllli 1Sll!I0v0t Plltr~Wlltlj Mvtltl-Vtse Trllill

}lpplication Por: Transportation Alternatives Projects Funding FY 2021 AVvleLLllI !sLl!I0v0t TrllILL Pvtlltse !! (AVvleLLllI 1sLl!I0v0t Plltr~Wlltlj MvtLtL-vtse TrllILL) Joint{y Su6mitted(By: Nassau County Board of Commissioners & City Commission of Fernandina Beach Su6mitted <To: North Florida Transportation Planning Orginization August 1, 2014 :Nassau County qrowth :Management <Department Contents: 1. Application Form For Transportation Alternatives Projects 2. Exhibits(Tabs): Exhibit A - Application Text Response to Questions 2.A - 2.E Exhibit B - Application Text Response to Questions 3 .A - 3 .E Exhibit C - Map Series AIT-II Exhibit D - Map 8 of Map Series RMP2030 Exhibit E - NFTPO(aka. FCMPO) Regional Greenways and Trail Plan(2006) excerpts; pages 16, 17, 28-30 Exhibit F - Florida Greenways and Trails System Plan(FGTS) Land Trail Opportunity and Priority Network excerpts Exhibit G - Florida Greenways & Trails Foundation, Inc., 'Close the Gap' excerpts Exhibit H - East Coast Greenway Florida Route Map Exhibit I - ROW Maps/Plats Compact Disk Exhibit J - Letters of Support Exhibit K - City of Fernandina Beach Resolution 2014-58 Exhibit L - Nassau County Board of Commissioners Meeting Minutes and Agenda Packet Exhibit M - Cost Estimates .... ::-.· __ . ... - ..=---=--:--- -_:- FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION District 2 APPLICATION FOR TRANSPORTATION November 2012 ALTERNATIVES PROJECTS Page rot 4 Oate: AUGUST 1, 2014 Project Title: AMELIA ISLAND TRAIL PHASE II {AMELIA ISLAND PARKWAY MULTI-USE TRAIL) Project Sponsor (name of city, county, state, federal agency, or MPO): NASSAU COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS AND THE CITY COMMISSION OF FERNANDINA BEACH (JOINT APPLICANTS) Contact TACO E. POPE. AICP Title SENIOR PLANNER Agency NASSAU COUNTY BOCC Address 96161 NAssAu PLACE, vuLEE, FL 32097 Phone (904) 491-7328 Email [email protected] Priority (relative to other applications submitted by the Project Sponsor) _F1_R_ST_PR_1_o_R1_TY_____ _ Name of Applicant (If other than contact person) _sA_M_E _________________ 1. -

Meeting Notice

The Original Florida TOURISM TASK FORCE MEETING NOTICE There will be a meeting of the Original Florida Tourism Task Force on April 20, 2017. The meeting will be held at the Monticello-Jefferson County Chamber of Commerce, 420 W. Washington Street, Monticello, FL, beginning at 10:00 a.m. (Location Map on Back) r:\original florida\task force meetings\agendas\2017\ofttf agenda 4-20-17.docx 1 r:\original florida\task force meetings\agendas\2017\ofttf agenda 4-20-17.docx 2 The Original Florida TOURISM TASK FORCE Meeting Agenda Monticello-Jefferson County Chamber of Commerce 420 West Washington Street, Monticello, FL April 20, 2017 Jefferson County 10:00 a.m. PAGE NO. I. Call to Order, Introductions II. Approval of the Agenda 3 III. Approval of the March 16, 2017 Meeting Minutes 5 IV. Old Business A. Committee Reports 1. Finance Committee a. Monthly Financial Report Review and Approval, February 28, 2017 11 2. Marketing Committee a. Status Report B. Fiscal Year 2016-17 Regional Rural Development Grant 1. Contract Status 2. Draft Scope of Work 25 a. Website Enhancements and Digital Advertising Campaign i. Request for Proposals 31 b. Springs and Bicycle Microsite Updates c. Blogs d. Photography i. Draft Photographic Services Contract e. Domestic Travel Shows i. Bike New York Expo ii. Midwest Mountaineering Spring Expo 39 iii. Hershey RV Show iv. Tampa Boat Show 40 f. Print and Digital Advertising Campaigns 41 g. eNewsletters 45 h. Brochure Printing and Distribution i. Scholarships 61 i. Southeast Tourism Society Marketing College, May 14-19, 2017, Additional Scholarship Request 63 ii. -

Exhilarating! Or the Local Lakes and Ponds Attractions, Events Or Activities

www.vnnf.org • 877.955.2199 • 352.955.2199 • 877.955.2199 • www.vnnf.org Park, Lafayette Blue Springs State Park and Fanning Springs Springs Fanning and Park State Springs Blue Lafayette Park, Heritage Paddling Trail System. Apalachee Bay is one one is Bay Apalachee System. Trail Paddling Heritage coast for shipment to textile mills in England as well as New New as well as England in mills textile to shipment for coast Beautiful cabins at Stephen Foster, Suwannee River State State River Suwannee Foster, Stephen at cabins Beautiful ecological diversity on the Apalachee Bay Maritime Maritime Bay Apalachee the on diversity ecological and attractions you’ll love to explore. to love you’ll attractions and authentic Cracker farm at the Forest Capital Museum in Perry Perry in Museum Capital Forest the at farm Cracker authentic was used to carry cotton from the plantation belt to the the to belt plantation the from cotton carry to used was and cabins alternate every ten river miles down the trail. trail. the down miles river ten every alternate cabins and Be transported back in time, discovering history and and history discovering time, in back transported Be • Florida Heritage Highway (U.S. Highway 441). Highway (U.S. Highway Heritage Florida Museums and Towns — For a sense of life gone by, visit the the visit by, gone life of sense a For — Towns and Museums • Marks. From the early 1900s, this historic railroad corridor corridor railroad historic this 1900s, early the From Marks. map of the region and a listing of springs, state parks, events events parks, state springs, of listing a and region the of map Places to Stay — River camps with sleeping platforms platforms sleeping with camps River — Stay to Places • (U.S. -

House Districts (This Compilation Was Produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019)

Florida State Parks FY 2017-18 Data by 2019 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.4 billion direct economic impact • $158 million in sales tax revenue • 33,587 jobs supported • Over 28 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Hill, Walter Bryan “Mike” 0 2 Andre, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 28,135,146 393 338,807 Big Lagoon State Park 12,155,746 170 141,517 Perdido Key State Park 12,739,427 178 157,126 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,239,973 45 40,164 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,545,992 315 275,195 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,301,348 214 188,630 Blackwater River State Park 6,361,036 89 75,848 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 883,608 12 10,717 4 Ponder, Mel 2 46,877,022 657 564,936 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,896,093 111 88,633 Henderson Beach State Park 38,980,929 546 476,303 5 Drake, Brad 9 75,811,647 1062 881,589 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 Deer Lake State Park 1,654,544 23 19,939 Eden Gardens State Park 3,298,681 46 39,601 Falling Waters State Park 5,761,074 81 67,225 Florida Caverns State Park 12,217,659 171 135,677 Grayton Beach State Park 20,250,255 284 236,181 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 4,745,495 66 57,194 Three Rivers State Park 3,465,975 49 39,482 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 21,639,586 303 254,586 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 76,186,412 1,067 926,162 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 St. -

Newsletter 1

Market Edge October 2010 A WORD FROM THE EXECUTIVE EDITOR...SANDY HUFF After 9/11 I had a terrible time selling a astated economy of ours is really taking At the FOWA conference in travel story outside the US. Americans a toll.” Punta Gorda, I made a side trip to visit a simply cancelled their overseas trips, famous plant nursery. The owners told and stayed home. I switched to article He ofersed one suggestion: me that their ‘tropical’ plants were surpris- subjects inside North America. There was ingly cold hardy. That article went to plenty to say, and lots of editors eager for “I still get my writing assignments with Florida Gardening. A copy went to the close-to-home subjects. the old fashioned query letter. I was told CVB folks who hosted our conference. Now the recession has hit many by an editor yesterday, he was looking It wasn’t hook and bullet, but still good of those markets too. It’s a domino efect for very compelling stories or something advertising for Punta Gorda. – Americans are hunkering down, hoard- linked to a manufacturer that uses his A rose garden in Sarasota, gator hunt- ing their disposable income or helping magazine for articles.” ing in Immokalee, photo ops at the St. out of work family members. That means Bernie Keefer, a past president Augustine Alligator farm, a bird colony I fewer trips, boats, rods and reels, and of FOWA and a proliic writer, taught discovered right here in Safety Harbor – other outdoor toys. outdoor writing classes here in Pinellas all grist for the writing mill. -

2016 Edition TABLE of CONTENTS PARTICIPATINGVISIT NATURAL COUNTIES NORTH FLORIDA

BikingGUIDE POWERED BY 2016 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS PARTICIPATINGVISIT NATURAL COUNTIES NORTH FLORIDA 1 Table of Contents 3 Introduction 5 Bell Loop 6 Bowlegs Mainline Loop 7 Cedar Key 8 Cross City Mainline Loop 9 Florida's Big Bend Coastal Tour 11 Florida's Ichetucknee-O'leno State Trail 12 Florida's Nature Coast State Trail 13 Florida's Ochlockonee Bay Bike Trail 14 Four Freedoms Trail 15 Four Springs Loop 16 Gainesville to Lake Butler 17 Grand North Florida Tour 19 Gainesville-Hawthorne State Trail 20 Jasper to White Springs 21 Lake City - Lakes Loop 22 Madison County 100-Mile Loop 23 Mayo Loop 24 Mayo to R.O. Ranch 25 Monticello Century Loop 26 Moticello 60-Mile Loop SPONSORS OF VNNF 27 Palatka - Lake Butler State Trail 28 Perry to Econfina State Park 29 Santa Fe Lake Loop 30 Starke - Lake Butler Loop 31 Steinhatchee to Perry 32 Tallahassee - St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail 33 Trenton Loop 34 Woodpecker Loop Funding provided by the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity. 1 2 FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT VNNF.ORG/BIKE-GUIDE FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT VNNF.ORG/BIKE-GUIDE 23 The two multi-day routes are not segmented by day. Rather, given significant differences in the INTRODUCTION abilities of riders, it is left up to them to determine how many miles can be ridden in a day and to plan overnight stays accordingly. The routes are available through the Visit Natural North Florida website. Please visit us at www.vnnf.org/bikeguide. The website provides maps, elevations, cue sheets and descriptions. -

Florida Bike Touring and State Trail Public Camping Options

Florida Bike Touring and State Trail Public Camping Options Helpful links to plan a bike tour in Florida: • Bike Florida (check out current and past routes for their annual trips). • East Coast Greenway, Florida Section. Part of the route covers the St. Johns River to Sea Loop (check on link for route maps). • Adventure Cycling Association – Florida Connector. This group also features information about the U.S. Bicycle Route System. There are more than 45,000 miles of adventure cycling routes. • Suwannee Bicycle Association: They provide a link to road cycling routes in the upper Suwannee River region. A good place to camp near White Springs is at Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State Park. • Florida Bicycle Association: They keep up a statewide touring calendar and they also link to bicycle clubs around the state. • Rails-to-Trails Conservancy: Their comprehensive TraillLink site covers multi-use paved bike trail information in Florida. • Florida Department of Transportation Bike Route Viewer: This interactive map shows all the state roads (and a lot of local roads) along with variables of interest to bicyclists, such as whether there is a bike lane or paved shoulder; the speed limit of the road, and the daily traffic. This will let you “roll yer own” bike route based on the criteria of most concern to you. It also includes the State paved trails, State Parks, US Bike Routes, and Adventure Cycling routes. If you zoom in far enough, it will drop you into StreetView so you can actually see the area you are interested in visiting. • Florida Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities (FDOT): This page has information about bicycling on-road in Florida, and includes contacts for each FDOT District Bike/Ped Coordinators and other organizations that support bike touring in Florida.