No Problem with No Consent Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Peter Q3 2020.Pdf

The Jersey Boys’ lastSee Page 16 march Autumn2020 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Featured What’s new in St Peter? Very little - things have gone Welcomereally quiet it seems, so far as my in-box is concerned anyway. Although ARTICLES the Island has moved to Level 1 of the Safe Exit Framework and many businesses are returning to some kind of normal, the same cannot be said of the various associations within the Parish, as you will see from 6 Helping Wings hope to fly again the rather short contributions from a few of the groups who were able to send me something. Hopefully this will change in the not too distant future, when social distancing returns to normal. There will be a lot of 8 Please don’t feed the Seagulls catching up to do and, I am sure, much news to share in Les Clefs. Closed shops So in this autumn edition, a pretty full 44 pages, there are some 10 offerings from the past which I hope will provide some interesting reading and visual delight. With no Battle of Flowers parades this year, 12 Cash for Trash – Money back on Bottles? there’s a look back at the 28 exhibits the Parish has entered since 1986. Former Constable Mac Pollard shares his knowledge and experiences about St Peter’s Barracks and ‘The Jersey Boys’, and we learn how the 16 The Jersey Boys last march retail sector in the Parish has changed over the years with an article by Neville Renouf on closed shops – no, not the kind reserved for union members only! We also learn a little about the ‘green menace’ in St 20 Hey Mr Bass Man Aubin’s Bay and how to refer to and pronounce it in Jersey French, and after several complaints have been received at the Parish Hall, some 22 Floating through time information on what we should be doing about seagulls. -

States of Jersey Statistics Unit

States of Jersey Statistics Unit Jersey in Figures 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents……………………………………………. i Foreword……………………………………………………… ii An Introduction to Jersey………………...…………………. iii Key Indicators……………………………………...………… v Chapter 1 Size and Land Cover of Jersey ………….………………… 1 2 National Accounts…………………...…………….………... 2 3 Financial Services…………………………………….……... 9 4 Tourism……………………………………………………….. 13 5 Agriculture and Fisheries………………………….………... 16 6 Employment………..………………………………………… 19 7 Prices and Earnings………………………………….……... 25 8 States of Jersey Income and Expenditure..………………. 30 9 Tax Receipts…………………………………………….…… 34 10 Impôts………………………………………………………… 38 11 Population…………………………………………….……… 40 12 Households…………………………………………….…….. 45 13 Housing…………………………………………………….…. 47 14 Education…………………………………………………….. 51 15 Culture and Heritage….……………………………….……. 53 16 Health…………………………………………………….…… 56 17 Crime…………………………………………………….……. 59 18 Jersey Fire Service………………………………………….. 62 19 Jersey Ambulance Service…………………………………. 64 20 Jersey Coastguard…………………………………………... 66 21 Social Security………………………………………….……. 68 22 Overseas Aid……………………………………...…….…… 70 23 Sea and Air Transport…………………………………....…. 71 24 Vehicle Transport……………………………………………. 74 25 Energy and Environment..………………………………...... 78 26 Water…………………………………………………………. 82 27 Waste Management……………………………………….... 86 28 Climate……………………………………………………….. 92 29 Better Life Index…………………………………………….. 94 Key Contacts………………………………………………… 96 Other Useful Websites……………………………………… 98 Reports Published by States of Jersey Statistics -

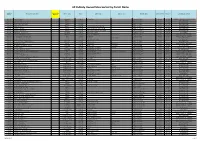

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name Sorted by Proposed for Then Sorted by Site Name Site Use Class Tenure Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Vingtaine Name Address Parish Postcode Controlling Department Parish Disposal Grouville 2 La Croix Crescent Residential Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DA COMMUNITY & CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS Grouville B22 Gorey Village Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EB INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B37 La Hougue Bie - La Rocque Highway Freehold Vingtaine de la Rue Grouville JE3 9UR INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B70 Rue a Don - Mont Gabard Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 6ET INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B71 Rue des Pres Highway Freehold La Croix - Rue de la Ville es Renauds Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DJ INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C109 Rue de la Parade Highway Freehold La Croix Catelain - Princes Tower Road Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE3 9UP INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C111 Rue du Puits Mahaut Highway Freehold Grande Route des Sablons - Rue du Pont Vingtaine de la Rocque Grouville JE3 9BU INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville Field G724 Le Pre de la Reine Agricultural Freehold La Route de Longueville Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE2 7SA ENVIRONMENT Grouville Fields G34 and G37 Queen`s Valley Agricultural Freehold La Route de la Hougue Bie Queen`s Valley Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EW HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES Grouville Fort William Beach Kiosk Sites 1 & 2 Land Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DY JERSEY PROPERTY HOLDINGS -

Town Crier the Official Parish of St Helier Magazine

TheSt Helier TOWN CRIER THE OFFICIAL PARISH OF ST HELIER MAGAZINE Image courtesy of the Jersey Evening Post JDC Waterfront update • States of Jersey Police: Licensing Support Team Conway Street redevelopment • Haute Vallée Year 11 Media Group View on St Helier • Parish Notice Board • Dates for your Diary • St Helier Gazette Delivered by Jersey Post to 19,000 homes and businesses every month. Designed and printed in Jersey by MailMate Publishing working in partnership with the Parish of St Helier. ESTABLISHED 1909 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Jersey Bachin Jersey Bowl Jersey Milk Can Available in Silver, Silver-plated and Copper in various sizes all suitable for engraving which can be done within 48 hours 3 King Street, St Helier, Jersey. JE2 4WF Tel: 01534 722536 www.pearcejewellers.co.uk FREEFRRREEE Tablet!TTaabablet! Get a FREE 7” Samsung Galaxy TabTab 3 and a FREE phone frfromom as little as £21 per month. Ask in storstoree for details or visit www.sure.comwww FREE RRP £199 While stocks last on selected phones, only on a 24 month contract. For full terms and conditionsconditions see www.sure.comwww.sure.com Welcome to the November issue of the Town Crier. From Jersey Eisteddfod also gets underway this month, giving early this month the Roll of Honour is once again on islanders of all ages the opportunity to perform on various display at the screen at Charing Cross, from Monday stages especially in the Jersey Opera House. Town 11th November at 11am, reminding us that we are traders will be particularly focused this month on half-way through the Royal British Legion's enhancing their appeal to shoppers in the run- Poppy Appeal which culminates with up to Christmas; several groups are now Remembrance Sunday and Armistice Day. -

Domestic Abuse Strategy for 2019-2022

DOMESTIC ABUSE STRATEGY 2019-2022 JERSEY SAFEGUARDING PARTNERSHIP BOARD DOMESTIC ABUSE STRATEGY 2019-2022 Page 1 of 17 DOMESTIC ABUSE STRATEGY 2019-2022 Advice and Support Domestic Abuse Contact Jersey Refuge Service 768368 Jersey Domestic Abuse Support 880505 Jersey Victim Support 440496 ADAPT (Domestic Abuse Perpetrators Programme) 07797924055 441916 Jersey Action Against Rape 482800 Family Mediation Jersey 638898 Sanctuary Trust – Men’s Shelter 743732 Dewberry House – S.A.R.C. 888222 Health Brook Centre 507981 Jersey Talking Therapies 444550 MIND Jersey 0800 7359404 Children / Young People Childline 0800 1111 NSPCC 760800 Barnardo’s 510546 Jersey Youth Service 280500 Youth Enquiry Service (YES) 280530 Andium Homes 500700 Page 2 of 17 DOMESTIC ABUSE STRATEGY 2019-2022 Customer and Local Services 445505 Crime Crimestoppers 0800 555111 States of Jersey Police Service 612612 Law Citizens Advice Bureau 0800 7350249 724942 Legal Aid Service 8001066 Emergencies Accident & Emergency Department 442000 Samaritans 7909090 Safeguarding Partnership Board Website https://safeguarding.je/ Page 3 of 17 DOMESTIC ABUSE STRATEGY 2019-2022 Forward It is estimated that one in four women and one in six men will experience domestic abuse at some point in their lifetime. Similarly, the impact of such abuse upon the lives of the children living in such environments cannot be underestimated. Reports of domestic abuse are increasing in Jersey and we must ensure that victims and their families are able to access the services they need, when they need them and at the earliest opportunity. We must provide coordinated services for the perpetrators of abuse to help stop the cycle of violence and we must help young people to understand what a healthy relationship is and to fully explain what is meant by controlling behaviour, violence, abuse and consent. -

Police Annual Report 2018

jersey. police.uk States of Jersey POLICE ANNUAL REPORT 2018 PHOTO CREDIT: Government of Jersey - Holly Smith Prepared by Jersey Police Annual Report 2018 Jersey Police Annual Report 2018 FOREWORD FOREWORD Article 20 of the States of Jersey Police (Jersey) Law 2012 It is with great pride and privilege that I, as acting Deputy makes it a duty of the Police Authority to provide a review of Chief Officer, provide the foreword for this year’s States the way the objectives of the Annual Policing Plan for 2018 of Jersey Police Annual Report. have been addressed by the States of Jersey Police (SOJP). 2018 was a year of many ‘firsts’ for SOJP. The first being our two-year Policing The 2018 Plan was the first to be written as a two-year plan, and I am pleased to Plan which runs across both 2018 and 2019. Our four priorities remain focussed note that over 21 objectives have been completed and that the remaining 11 are on protecting and preventing our most vulnerable from harm, strengthening on target for completion later this year. engagement within our communities with stronger partnership working to provide better outcomes, and a commitment to better your police service by investing in our As an Island with its own government and legislation, Jersey has a unique and people, technology and culture. distinct policing environment. The SOJP must be largely self-sufficient in developing and maintaining public services that in larger jurisdictions would be a collaborative During the first part of the year we undertook a critical review of how we organised process provided through a local, regional and national level police service and operated as a force. -

States of Jersey Police Annual Reports 2005-2010

STATES OF JERSEY POLICE ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2005 CONTENTS Page Number Chief Officer’s Introduction 3 Explanatory Notes 4 Key Performance Outcomes 5 Recorded Crime 6 Detection Rates 8 Road Safety 9 Public Confidence 12 Corporate Standards 16 Crime in Jersey 2005 18 Acquisitive Crime 21 Offences against the Person 22 Drugs 25 Financial Crime 26 Managing Change 27 Partnership with the Honorary Police 37 Glossary of Terms 38 Page 2 CHIEF OFFICER’S INTRODUCTION Thank you for reading the States of Jersey Police Annual Performance Report for 2005. Crime levels in Jersey continue to remain low compared with elsewhere and, in 2005, crime fell further compared with 2004 and the three-year average. This is to a large extent due to the exceptional efforts of the men and women of the Force and the strong support we receive from the public. In addition to normal operations in 2005 the force policed a number of major events. The most significant was the visit of Her Majesty the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh to attend the 60th Anniversary celebrations of the Liberation. The visit posed major operational challenges, including crowd control, transport and not least of all the significant security arrangements now required for events of this nature. The operation involved the full mobilisation of both the States and Honorary Police, and it is to the credit of all concerned that fewer than 20 officers from the U.K. were needed to supplement operations on the day. While this report describes low and falling levels of crime we should not become complacent. -

States of Jersey Police: Annual Report 2018

jersey. police.uk States of Jersey POLICE ANNUAL REPORT 2018 PHOTO CREDIT: Government of Jersey - Holly Smith R.64/2019 Prepared by Jersey Police Annual Report 2018 Jersey Police Annual Report 2018 FOREWORD FOREWORD Article 20 of the States of Jersey Police (Jersey) Law 2012 It is with great pride and privilege that I, as acting Deputy makes it a duty of the Police Authority to provide a review of Chief Officer, provide the foreword for this year’s States the way the objectives of the Annual Policing Plan for 2018 of Jersey Police Annual Report. have been addressed by the States of Jersey Police (SOJP). 2018 was a year of many ‘firsts’ for SOJP. The first being our two-year Policing The 2018 Plan was the first to be written as a two-year plan, and I am pleased to Plan which runs across both 2018 and 2019. Our four priorities remain focussed note that over 21 objectives have been completed and that the remaining 11 are on protecting and preventing our most vulnerable from harm, strengthening on target for completion later this year. engagement within our communities with stronger partnership working to provide better outcomes, and a commitment to better your police service by investing in our As an Island with its own government and legislation, Jersey has a unique and people, technology and culture. distinct policing environment. The SOJP must be largely self-sufficient in developing and maintaining public services that in larger jurisdictions would be a collaborative During the first part of the year we undertook a critical review of how we organised process provided through a local, regional and national level police service and operated as a force. -

22 St Saviour Q1 2014.Pdf

StSaviour-Spring2014-9-1 copy_Governance style ideas 14/03/2014 14:53 Page 1 SPRING2014 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 22 In this p 3 Out and about Meet the p issue 5 Peter Mourant re-elected Parishioner p 12 Astronomy Club p 16 Police feature Tony p 18 Clubs and associations Runacres p 21 La Clioche Cratchie p 9 p 24 Recycling StSaviour-Spring2014-9-1 copy_Governance style ideas 14/03/2014 14:53 Page 2 SPRING MENU OFFER Enjoy our fantastic spring menus and sample some of the islands freshest and tastiest dishes at a very special price 2 courses £13.50 3 courses £16.50 ENJOY OUR GREAT VALUE SPRING WINES Matra Hill Chilean, Concha Y Toro white, red & rose Sauvignon Blanc or Melot Only £10.80 Only £13.80 To view menus and other special offers www.taste2day.com Offers available at any of the pubs bars & eateries listed below StSaviour-Spring2014-9-1 copy_Governance style ideas 14/03/2014 14:54 Page 3 Spring2014 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 Out and About in the Parish Housing update Honorary Police update Major housing As we go to press it is announced that there are to be some changes within our development in Parish Honorary Police. Centenier Richard Langlois is not seeking re-election the Parish is well when his term culminates shortly and we shall also be losing our most on schedule. experienced training officer and Centenier, Louise Noel, who was a former The large Police Constable in the Cheshire Constabulary on the Mainland. Louise is construction resigning still having two years left to serve of her three year term of office. -

States of Jersey Police Force Law 2012 Arrangement

States of Jersey Police Force Law 2012 Arrangement STATES OF JERSEY POLICE FORCE LAW 2012 Arrangement Article Interpretation 3 1 Interpretation ................................................................................................... 3 States of Jersey Police Force 4 2 States of Jersey Police Force........................................................................... 4 Minister’s functions 4 3 Functions of Minister ...................................................................................... 4 Jersey Police Authority 5 4 Jersey Police Authority ................................................................................... 5 5 Membership of the Police Authority............................................................... 5 6 Meetings of the Police Authority .................................................................... 6 7 Power of Minister to direct the Police Authority ............................................ 7 Terms and conditions of appointment of police officers 7 8 Chief Officer and Deputy Chief Officer ......................................................... 7 9 Appointment of Chief Officer and Deputy Chief Officer ............................... 8 10 Appointments of other police officers ............................................................ 8 11 Terms and conditions of appointment of other police officers ....................... 9 12 Association of police officers ......................................................................... 9 13 General Orders ............................................................................................. -

Public Elections (Jersey) Law 2002

PUBLIC ELECTIONS (JERSEY) LAW 2002 General information for candidates for election and for proposers and seconders of candidates for election as Senator, Connétable or Deputy. 1. Qualification and disqualification for election to office are set out in: a. the States of Jersey Law 2005 – for election as Senator or Deputy, or b. the Connétables (Jersey) Law 2008 – for election as Connétable. 2. Nomination Document and Political Party Declaration must be completed by a candidate for election to the office of Senator, Connétable or Deputy. 3. Declaration of convictions must be made by all candidates for election to the office of Connétable (under the Connétables (Jersey) Law 2008), Senator or Deputy (under the States of Jersey Law 2005). 4. Office of Connétable - candidates for election should be aware that the Royal Court may refuse to swear a person to office if not satisfied that he or she is a fit and proper person to hold that office. Candidates may be asked to complete a basic criminal records check. 5. Candidate in one election only - the Public Elections (Jersey) Law 2002 provides that where 2 or more elections for one or more Senators, Deputies or Connétables are held on the same day, a person cannot be admitted as a candidate in more than one of those elections. Accordingly if a person is admitted as a candidate in an election and is subsequently admitted as a candidate in another of those elections then the earlier admission as a candidate shall lapse. 6. Electoral districts for each election are as follows: a. The Island of Jersey for the office of Senator b. -

States of Jersey Annual Report and Accounts 2020

States of Jersey 2020 Annual Report and Accounts Our purpose Our purpose as the Government of Jersey is to serve and represent the best interests of the Island and its citizens. In order to do this, we must: • Provide strong, fair and trusted leadership for the island and its people • Deliver positive, sustainable economic, social and environmental outcomes for Jersey • Ensure effective, efficient and sustainable management and use of public funds • Ensure the provision of modern and highly-valued services for the public. Scope of the Annual Report and Accounts While most matters within the Annual Report and Accounts are the responsibility of the Government of Jersey, this publication also covers the wider States of Jersey Group, including Non-Ministerial Departments and States-Owned Enterprises. As a result, there are references to both the Government of Jersey and, where appropriate, to the States of Jersey throughout this document. More detail on the specific accountabilities of the different parts of the public sector is contained within the accountability section of this report. Performance Report Accountability Report Primary Statements Notes to the Accounts Contents Performance Report 6 Chief Minister’s Foreword 7 Chief Executive’s Report 10 Section 1 – Introduction and Overview 13 Improving Performance Reporting in 2021 14 The Performance Implications of Covid-19 16 Section 2 - 2020 Performance Highlights 26 Strategic Priority – Put Children First 28 Strategic Priority – Health and Wellbeing 31 Strategic Priority – A sustainable,