Management of Cutaneous Hemangiomas in Pediatric Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No. 203 July 2004 Table of Contents 1. Serious skin disorders caused by pharmaceuticals ···················3 2. Effects of electromagnetic waves from antitheft devices, etc. on medical devices ······································7 3. Important Safety Information ··························································· 13 .1. Monoethanolamine Oleate ······························································· 13 .2. Clarithromycin ··················································································16 .3. Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil Potassium ·············································· 22 .4. Melphalan (injectable dosage form) ················································· 25 4. Revision of PRECAUTIONS (No. 157) Milnacipran Hydrochloride (and 6 others) ···················································30 This Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information (PMDSI) is issued based on safety information collected by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. It is intended to facilitate safer use of pharmaceuticals and medical devices by healthcare providers. PMDSI is available on the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website (http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/index.html) and on the MHLW website (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/, Japanese only). Published by Translated by Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Office of Safety, Ministry -

Pruritus: Scratching the Surface

Pruritus: Scratching the surface Iris Ale, MD Director Allergy Unit, University Hospital Professor of Dermatology Republic University, Uruguay Member of the ICDRG ITCH • defined as an “unpleasant sensation of the skin leading to the desire to scratch” -- Samuel Hafenreffer (1660) • The definition offered by the German physician Samuel Hafenreffer in 1660 has yet to be improved upon. • However, it turns out that itch is, indeed, inseparable from the desire to scratch. Savin JA. How should we define itching? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Pt 1):268-9. Pruritus • “Scratching is one of nature’s sweetest gratifications, and the one nearest to hand….” -- Michel de Montaigne (1553) “…..But repentance follows too annoyingly close at its heels.” The Essays of Montaigne Itch has been ranked, by scientific and artistic observers alike, among the most distressing physical sensations one can experience: In Dante’s Inferno, falsifiers were punished by “the burning rage / of fierce itching that nothing could relieve” Pruritus and body defence • Pruritus fulfils an essential part of the innate defence mechanism of the body. • Next to pain, itch may serve as an alarm system to remove possibly damaging or harming substances from the skin. • Itch, and the accompanying scratch reflex, evolved in order to protect us from such dangers as malaria, yellow fever, and dengue, transmitted by mosquitoes, typhus-bearing lice, plague-bearing fleas • However, chronic itch lost this function. Chronic Pruritus • Chronic pruritus is a common and distressing symptom, that is associated with a variety of skin conditions and systemic diseases • It usually has a dramatic impact on the quality of life of the affected individuals Chronic Pruritus • Despite being the major symptom associated with skin disease, our understanding of the pathogenesis of most types of itch is limited, and current therapies are often inadequate. -

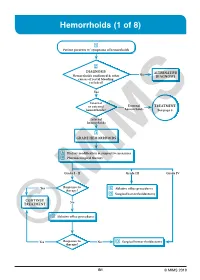

Hemorrhoids (1 of 8)

Hemorrhoids (1 of 8) 1 Patient presents w/ symptoms of hemorrhoids 2 DIAGNOSIS No ALTERNATIVE Hemorrhoids confi rmed & other DIAGNOSIS causes of rectal bleeding excluded? Yes Internal or external External TREATMENT hemorrhoids? hemorrhoids See page 3 Internal hemorrhoids 3 GRADE HEMORRHOIDS A Dietary modifi cation & supportive measures B Pharmacological therapy Grade I - II Grade III Grade IV Yes Response to C Ablative offi ce procedures therapy? D Surgical hemorrhoidectomy CONTINUE No TREATMENT C Ablative offi ce procedures Yes Response to No D Surgical hemorrhoidectomy ©therapy? MIMS B1 © MIMS 2019 Hemorrhoids (2 of 8) 1 SYMPTOMS ATTRIBUTED TO HEMORRHOIDS • Rectal bleeding - Most common presenting symptom - Bright red blood which may drip or squirt into the toilet bowl or scanty amounts may be seen on toilet tissue • Discomfort due to rectal protrusion or lump • Anal pain • HEMORRHOIDS Anal itching 2 DIAGNOSIS Medical History • Assess nature, duration & severity of symptoms - Ask about bleeding, its amount & frequency - Ask about presence of prolapsing tissue, its timing & reproducibility • Elicit possible risk factors for development of hemorrhoidal symptoms - Low-fi ber diets cause small-caliber stools, resulting in straining during defecation & engorgement of hemorrhoids - Prolonged sitting on a toilet which may cause a problem in the venous return in the perianal area - Pregnancy - Advanced age • Th e signs & symptoms of hemorrhoids are not specifi c to the disease, so care must be taken to avoid missing other causes of pathology • Obtain -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Diagnosis and Treatment of Varicose Veins in the Legs

Diagnosis and treatment of varicose veins in the legs KCE reports 164C Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg Centre fédéral d’expertise des soins de santé 2011 The Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre Introduction: The Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) is an organization of public interest, created on the 24th of December 2002 under the supervision of the Minister of Public Health and Social Affairs. KCE is in charge of conducting studies that support the political decision making on health care and health insurance. Executive Board Actual Members: Pierre Gillet (President), Dirk Cuypers (Vice-president), Jo De Cock (Vice-president), Frank Van Massenhove (Vice-president), Maggie De Block, Jean-Pierre Baeyens, Ri de Ridder, Olivier De Stexhe, Johan Pauwels, Daniel Devos, Jean-Noël Godin, Xavier De Cuyper, Paul Palstermans, Xavier Brenez, Rita Thys, Marc Moens, Marco Schetgen, Patrick Verertbruggen, Michel Foulon, Myriam Hubinon, Michael Callens, Bernard Lange, Jean-Claude Praet. Substitute Members: Rita Cuypers, Christiaan De Coster, Benoît Collin, Lambert Stamatakis, Karel Vermeyen, Katrien Kesteloot, Bart Ooghe, Frederic Lernoux, Leo Neels, Greet Musch, Geert Messiaen, Anne Remacle, Roland Lemeye, Annick Poncé, Pierre Smiets, Jan Bertels, Celien Van Moerkerke, Yolande Husden, Ludo Meyers, Olivier Thonon, François Perl. Government commissioner: Yves Roger Management Chief Executive Officer: Raf Mertens Assistant Chief Executive Officer: Jean-Pierre Closon Information Federaal Kenniscentrum -

Basic Skin Care and Topical Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis

REVIEWS Basic Skin Care and Topical Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis: Essential Approaches and Beyond Sala-Cunill A1*, Lazaro M2*, Herráez L3, Quiñones MD4, Moro-Moro M5, Sanchez I6, On behalf of the Skin Allergy Committee of Spanish Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (SEAIC) 1Allergy Section, Internal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain 2Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Alergoasma, Salamanca, Spain 3Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain 4Allergy Section, Hospital Monte Naranco, Oviedo, Spain 5Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain 6Clínica Dermatología y Alergia, Badajoz, Spain *Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018; Vol. 28(6): 379-391 doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0293 Abstract Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a recurrent and chronic skin disease characterized by dysfunction of the epithelial barrier, skin inflammation, and immune dysregulation, with changes in the skin microbiota and colonization by Staphylococcus aureus being common. For this reason, the therapeutic approach to AD is complex and should be directed at restoring skin barrier function, reducing dehydration, maintaining acidic pH, and avoiding superinfection and exposure to possible allergens. There is no curative treatment for AD. However, a series of measures are recommended to alleviate the disease and enable patients to improve their quality of life. These include adequate skin hydration and restoration of the skin barrier with the use of emollients, antibacterial measures, specific approaches to reduce pruritus and scratching, wet wrap applications, avoidance of typical AD triggers, and topical anti-inflammatory drugs. Anti-inflammatory treatment is generally recommended during acute flares or, more recently, for preventive management. -

Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization

No. 31874 Multilateral Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organ ization (with final act, annexes and protocol). Concluded at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994 Authentic texts: English, French and Spanish. Registered by the Director-General of the World Trade Organization, acting on behalf of the Parties, on 1 June 1995. Multilat ral Accord de Marrakech instituant l©Organisation mondiale du commerce (avec acte final, annexes et protocole). Conclu Marrakech le 15 avril 1994 Textes authentiques : anglais, français et espagnol. Enregistré par le Directeur général de l'Organisation mondiale du com merce, agissant au nom des Parties, le 1er juin 1995. Vol. 1867, 1-31874 4_________United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités 1995 Table of contents Table des matières Indice [Volume 1867] FINAL ACT EMBODYING THE RESULTS OF THE URUGUAY ROUND OF MULTILATERAL TRADE NEGOTIATIONS ACTE FINAL REPRENANT LES RESULTATS DES NEGOCIATIONS COMMERCIALES MULTILATERALES DU CYCLE D©URUGUAY ACTA FINAL EN QUE SE INCORPOR N LOS RESULTADOS DE LA RONDA URUGUAY DE NEGOCIACIONES COMERCIALES MULTILATERALES SIGNATURES - SIGNATURES - FIRMAS MINISTERIAL DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS AND UNDERSTANDING DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS ET MEMORANDUM D©ACCORD MINISTERIELS DECISIONES, DECLARACIONES Y ENTEND MIENTO MINISTERIALES MARRAKESH AGREEMENT ESTABLISHING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION ACCORD DE MARRAKECH INSTITUANT L©ORGANISATION MONDIALE DU COMMERCE ACUERDO DE MARRAKECH POR EL QUE SE ESTABLECE LA ORGANIZACI N MUND1AL DEL COMERCIO ANNEX 1 ANNEXE 1 ANEXO 1 ANNEX -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

Updated June 07, 2021 Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Three categories of bulk drug substances: • Category 1: Bulk Drug Substances Under Evaluation • Category 2: Bulk Drug Substances that Raise Significant Safety Risks • Category 3: Bulk Drug Substances Nominated Without Adequate Support Updates to Categories of Substances Nominated for the 503B Bulk Drug Substances List1 • Add the following entry to category 2 due to serious safety concerns of mutagenicity, cytotoxicity, and possible carcinogenicity when quinacrine hydrochloride is used for intrauterine administration for non- surgical female sterilization: 2,3 o Quinacrine Hydrochloride for intrauterine administration • Revision to category 1 for clarity: o Modify the entry for “Quinacrine Hydrochloride” to “Quinacrine Hydrochloride (except for intrauterine administration).” • Revision to category 1 to correct a substance name error: o Correct the error in the substance name “DHEA (dehydroepiandosterone)” to “DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone).” 1 For the purposes of the substance names in the categories, hydrated forms of the substance are included in the scope of the substance name. 2 Quinacrine HCl was previously reviewed in 2016 as part of FDA’s consideration of this bulk drug substance for inclusion on the 503A Bulks List. As part of this review, the Division of Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Products (DBRUP), now the Division of Urology, Obstetrics and Gynecology (DUOG), evaluated the nomination of quinacrine for intrauterine administration for non-surgical female sterilization and recommended that quinacrine should not be included on the 503A Bulks List for this use. This recommendation was based on the lack of information on efficacy comparable to other available methods of female sterilization and serious safety concerns of mutagenicity, cytotoxicity and possible carcinogenicity in use of quinacrine for this indication and route of administration. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen Et Al

US008821928B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 2, 2014 (54) CONTROLLED RELEASE 5,869,097 A 2/1999 Wong et al. PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR 6,103,261 A 8, 2000 Chasin et al. 2003.01.18641 A1 6/2003 Maloney et al. PROLONGED EFFECT 2003/O133976 A1* 7/2003 Pather et al. .................. 424/466 2004/O151772 A1 8/2004 Andersen et al. (75) Inventors: Pernille Hoyrup Hemmingsen, 2005.0053655 A1 3/2005 Yang et al. Bagsvaerd (DK); Anders Vagno 2005/O158382 A1* 7/2005 Cruz et al. .................... 424/468 2006, O1939 12 A1 8, 2006 KetSela et al. Pedersen, Virum (DK); Daniel 2007/OOO3617 A1 1/2007 Fischer et al. Bar-Shalom, Kokkedal (DK) 2007,0004797 A1 1/2007 Weyers et al. (73) Assignee: Egalet Ltd., London (GB) 2007. O190142 A1 8, 2007 Breitenbach et al. (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 1052 days. DE 202006O14131 1, 2007 EP O435,726 8, 1991 (21) Appl. No.: 12/602.953 (Continued) (22) PCT Filed: Jun. 4, 2008 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/056910 Krogel etal (Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 15, 1998, pp. 474-481).* Notification of Transmittal of the International Search Report and the S371 (c)(1), Written Opinion of the International Searching Authority issued Jul. (2), (4) Date: Jun. 7, 2010 8, 2008 in International Application No. PCT/DK2008/000016. International Preliminary Reporton Patentability issued Jul. -

Vein Medication Experts

Vein Medication Experts Purchase vein care medications directly from an FDA 503B Outsourcing Facility Olympia Compounding Pharmacy is a registered and inspected FDA Outsourcing Facility in Orlando, FL. Because of the extremely high standards required to operate as an FDA facility, there are only fifty FDA compounders in the United States at this time. All compounded items from Olympia Pharmacy are compounded under the new cGMP guidelines to insure the safest, highest quality compounded medications available. For more information, or to open an account please contact: Dan Powell Director of Business Development for Olympia Pharmacy Direct: 407-383-7644 Email: [email protected] Olympia Pharmacy | FDA Outsourcing Facility | 6700 Conroy Rd, Orlando FL 32835| Ph: 407-673-2222 |olympiapharmacy.com Polidocanol / STS Price List - Physicians Prescription Fax: 407-673-1234 Shipping: [ ] UPS Ground [ ] UPS 2nd Day [ ] UPS next business day Physician/Practice Name: ______________________________________________________________________ Ship to Address: ___________________________________________________ Phone: ____________________ City/State/Zip: ________________________________________________ Fax: ____________________ Physician License: ________________________________ Drug Concentration Volume Price Order Qty Polidocanol 1.25%, 1.5% 5ml $28 Polidocanol 3% 5ml $33 Polidocanol 5% 5ml $40 Polidocanol 10% 5ml $50 Glycerin 72%/ Lidocaine 1%/ with Epinephrine 1:100,000 N/A 5ml $24 Glycerin 72% Plain N/A 5ml $28 Nifedipine Ointment 0.3%/ N/A 30g