In Eastern Partner Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Howard County Retirement Plans Meeting Materials

MEETING MATERIALS HOWARD COUNTY RETIREMENT PLANS April 29, 2021 Margaret Belmondo, CIMA®, Partner Will Forde, CFA, CAIA, Principal Francesca LoVerde, Senior Consulting Analyst BOSTON | ATLANTA | CHARLOTTE | CHICAGO | DETROIT | LAS VEGAS | PORTLAND | SAN FRANCISCO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page March Flash Report 3 Correlation & Stochastic Analysis 12 High Yield Search Book 19 2 MARCH FLASH REPORT NEPC, LLC 3 CALENDAR YEAR INDEX PERFORMANCE 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Mar YTD S&P 500 2.1% 16.0% 32.4% 13.7% 1.4% 12.0% 21.8% -4.4% 31.5% 18.4% 4.4% 6.2% Russell 1000 1.5% 16.4% 33.1% 13.2% 0.9% 12.1% 21.7% -4.8% 31.4% 21.0% 3.8% 5.9% Russell 2000 -4.2% 16.3% 38.8% 4.9% -4.4% 21.3% 14.6% -11.0% 25.5% 20.0% 1.0% 12.7% Russell 2500 -2.5% 17.9% 36.8% 7.1% -2.9% 17.6% 16.8% -10.0% 27.8% 20.0% 1.6% 10.9% MSCI EAFE -12.1% 17.3% 22.8% -4.9% -0.8% 1.0% 25.0% -13.8% 22.0% 7.8% 2.3% 3.5% MSCI EM -18.4% 18.2% -2.6% -2.2% -14.9% 11.2% 37.3% -14.6% 18.4% 18.3% -1.5% 2.3% MSCI ACWI -7.3% 16.1% 22.8% 4.2% -2.4% 7.9% 24.0% -9.4% 26.6% 16.3% 2.7% 4.6% Private Equity 9.5% 12.6% 22.3% 14.6% 10.4% 10.3% 21.0% 13.1% 17.2% 13.0%* - - BC TIPS 13.6% 7.0% -8.6% 3.6% -1.4% 4.7% 3.0% -1.3% 8.4% 11.0% -0.2% -1.5% BC Municipal 10.7% 6.8% -2.6% 9.1% 3.3% 0.2% 5.4% 1.3% 7.5% 5.2% 0.6% -0.4% BC Muni High Yield 9.2% 18.1% -5.5% 13.8% 1.8% 3.0% 9.7% 4.8% 10.7% 4.9% 1.1% 2.1% BC US Corporate HY 5.0% 15.8% 7.4% 2.5% -4.5% 17.1% 7.5% -2.1% 14.3% 7.1% 0.1% 0.8% BC US Agg Bond 7.8% 4.2% -2.0% 6.0% 0.5% 2.6% 3.5% 0.0% 8.7% 7.5% -1.2% -3.4% BC Global Agg 5.6% 4.3% -2.6% -

Services & Offerings

STAG DINING 2020 SERVICES & OFFERINGS Meal Kits - Pantry Provisions - Natural Wine - Gifting - Cocktail Kits & Classes - Event Space - Crenn Farm 1 LETTER FROM STAG 4 STAG DINING GROUP STAG OVERVIEW MEAL KITS & OFFERINGS 8 NATURAL WINES 10 COCKTAIL KITS & CLASSES 12 WINEMAKING PARTNERS 16 CRENN & STAG 18 OUR VENUE 22 CLIENTS 27 TEAM 28 CONTACT 32 STAG DINING GROUP 925 O'Farrell St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 944-2065 [email protected] www.stagdining.com DERBY COCKTAIL CO www.derbycocktail.co CERF CLUB www.cerfclub.com © 2020 Stag Dining Group Select Photography by David Dines, dines.co 2 3 WITH A DECADE OF EXPERIENCE IN HOSPITALITY, WE HAVE NEVER SEEN A CHALLENGE THAT FACES US QUITE LIKE THE ONE POSED BY COVID-19. With virtually every restaurant worker out of a job, and traditional supply chains for food, wine and spirits broken, we have been UPDATED OFFERINGS seeking opportunities to mend those bonds in pragmatic ways while continuing to serve our customers. Our revised offerings are an attempt to help our clients engage their stakeholders, employees MEAL KITS and clients in ways that are fitting for this time and address the social, racial, environmental and biological crises that we are PANTRY PROVISIONS facing collectively as a society. NATURAL WINE At Stag Dining Group we believe every plate and every glass GIFTING tells a unique story, and we make every effort to connect guests COCKTAIL KITS & CLASSES to each other, to the environment and to the thought leaders of CRENN FARM this industry in authentic ways. Since our inception, we have witnessed the power that transformative culinary experiences have CERF CLUB EVENT VENUE on our guests and the conversations that can be sparked at the table. -

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W. Newhall III William H. Draper III Interview Conducted and Edited by Mauree Jane Perry October, 2005 All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the National Venture Capital Association. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the National Venture Capital Association. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the National Venture Capital Association, 1655 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 850, Arlington, Virginia 22209, or faxed to: 703-524-3940. All requests should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Copyright © 2009 by the National Venture Capital Association www.nvca.org This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 2% of US GDP and was responsible for 10.4 million American jobs and 2.3 trillion in sales. -

The Handbook of Financing Growth

ffirs.qxd 2/15/05 12:30 PM Page iii The Handbook of Financing Growth Strategies and Capital Structure KENNETH H. MARKS LARRY E. ROBBINS GONZALO FERNÁNDEZ JOHN P. FUNKHOUSER John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 2/15/05 12:30 PM Page b ffirs.qxd 2/15/05 12:30 PM Page a Additional Praise For The Handbook of Financing Growth “The authors have compiled a practical guide addressing capital formation of emerging growth and middle-market companies. This handbook is a valuable resource for bankers, accountants, lawyers, and other advisers serving entrepreneurs.” Alfred R. Berkeley Former President, Nasdaq Stock Market “Not sleeping nights worrying about where the capital needed to finance your ambitious growth opportunities is going to come from? Well, here is your answer. This is an outstanding guide to the essential planning, analy- sis, and execution to get the job done successfully. Marks et al. have cre- ated a valuable addition to the literature by laying out the process and providing practical real-world examples. This book is destined to find its way onto the shelves of many businesspeople and should be a valuable ad- dition for students and faculty within the curricula of MBA programs. Read it! It just might save your company’s life.” Dr. William K. Harper President, Arthur D. Little School of Management (Retired) Director, Harper Brush Works and TxF Products “Full of good, realistic, practical advice on the art of raising money and on the unusual people who inhabit the American financial landscape. It is also full of information, gives appropriate warnings, and arises from a strong ethical sense. -

How to Catch a Unicorn

How to Catch a Unicorn An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation Author: Jean Paul Simon Editor: Marc Bogdanowicz 2016 EUR 27822 EN How to Catch a Unicorn An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s in-house science service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policy-making process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. JRC Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC100719 EUR 27822 EN ISBN 978-92-79-57601-0 (PDF) ISSN 1831-9424 (online) doi:10.2791/893975 (online) © European Union, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. All images © European Union 2016 How to cite: Jean Paul Simon (2016) ‘How to catch a unicorn. An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation’. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. JRC Technical Report. EUR 27822 EN. doi:10.2791/893975 Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................. 2 Abstract ............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary .......................................................................................... -

Download the Full Report

SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 1 SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 2 Editor: Javier Santiso, PhD Associate Professor, ESADE Business School Vice President, ESADEgeo - Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 3 Index Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Direct investing by sovereign wealth funds in 2014: The worst of times, the best of times 11 I Geographic Analysis 21 Sovereign wealth funds in Spain and Latin America: Spain's consolidation as an investment destination 23 Sovereign wealth funds from Muslim countries: Driving the Halal industry and Islamic finance 37 Different twins and a distant cousin: Sovereign wealth funds in Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea 51 II Sector Analysis 65 Sovereign wealth funds and the geopolitics of agriculture 67 Sovereign Venture Funds 79 The kings of the king of sports: Sovereign wealth funds and football 95 Financing of the digital ecosystem: The “disruptive” role of SWFs…Reconsidered 109 Sovereign wealth funds and heritage assets: An investor’s perspective 121 ANNEX. ESADEgeo Sovereign Wealth Funds Ranking 2015 133 Sovereign wealth funds 2015 Index 3 SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 4 SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 5 Preface SovereignWealthFunds15:Maquetación 1 20/10/15 17:57 Página 6 1. Preface The pattern of world economic growth during 2015 has undergone In both 2014 and 2015 developed and emerging countries' a significant change relative to previous years. While the developed sovereign wealth funds have continued to feature prominently in economies succeeded in shaking off their lethargy and improving significant strategic transactions worldwide. -

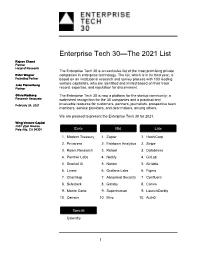

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List Rajeev Chand Partner Head of Research The Enterprise Tech 30 is an exclusive list of the most promising private Peter Wagner companies in enterprise technology. The list, which is in its third year, is Founding Partner based on an institutional research and survey process with 103 leading venture capitalists, who are identified and invited based on their track Jake Flomenberg Partner record, expertise, and reputation for discernment. Olivia Rodberg The Enterprise Tech 30 is now a platform for the startup community: a Research Associate watershed recognition for the 30 companies and a practical and February 24, 2021 invaluable resource for customers, partners, journalists, prospective team members, service providers, and deal makers, among others. We are pleased to present the Enterprise Tech 30 for 2021. Wing Venture Capital 480 Lytton Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94301 Early Mid Late 1. Modern Treasury 1. Zapier 1. HashiCorp 2. Privacera 2. Fishtown Analytics 2. Stripe 3. Roam Research 3. Retool 3. Databricks 4. Panther Labs 4. Netlify 4. GitLab 5. Snorkel AI 5. Notion 5. Airtable 6. Linear 6. Grafana Labs 6. Figma 7. ChartHop 7. Abnormal Security 7. Confluent 8. Substack 8. Gatsby 8. Canva 9. Monte Carlo 9. Superhuman 9. LaunchDarkly 10. Census 10. Miro 10. Auth0 Special Calendly 1 2021 The Curious Case of Calendly This year’s Enterprise Tech 30 has 31 companies rather than 30 due to the “curious case” of Calendly. Calendly, a meeting scheduling company, was categorized as Early-Stage when the ET30 voting process started on January 11 as the company had raised $550,000. -

Portfolio Management Revolution Technology Trending Paper Silicon Valley, CA Q4 2014

The Portfolio Management Revolution Technology Trending Paper Silicon Valley, CA Q4 2014 The Portfolio Management Revolution Over the past few years, a new crop of online wealth man- agement startups has come on the scene, threatening to disrupt a profitable business line once the sole province of banks and private advisors. Betterment, for example, in four years has On the back end, technology startups such grown to over 50,000 customers and man- as Addepar, MyVest, and Kensho are serving ages more than $1B in assets. Such consum- wealth managers and private bankers by pro- er-facing services, known as robo-advisors, viding platforms that increase efficiency, feed also include Wealthfront, SigFig, Personal intelligence on market moving global trends, Capital, FutureAdvisor, and several others. and otherwise bring portfolio management into the 21st century. The emerging class of portfolio analytics Venture capital (VC) has pumped $800M into startups represent the new face of wealth man- the space over the last two years, recognizing agement, and their popularity attests to this. the runaway popularity of the new services and Many of the consumer-facing startups are aimed the vast potential for profitability. Investment is at the younger picking up speed. In generations, which the second quarter have high expecta- As wealth is transferred of 2014 alone, tions and, in many from the boomer investment in per- cases, are ignored sonal finance ser- by traditional pri- generation to generations vices was $261M, vate wealth man- according to CB agers and banks X and Y, it will represent Insights. who doubt the a $41T opportunity. -

Financial Services Deals for July 2018

Financial Services Deals for July 2018 Company Name Description Deal Synopsis Ajax Health Provider of operational and financial support to the The company received $124.97 million of development capital emerging medical device companies. The company from Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Aisling Capital, Iconiq Capital, operates healthcare companies that address significant HealthQuest Capital, Polaris Partners, WTI and other unmet needs by developing emerging medical device undisclosed investors on July 19, 2018. technologies and focuses on improving lives and bringing speed, simplicity and cost efficiency to healthcare. Applied Data Finance Developer of consumer financial platform intended for The company raised $145 million of development capital from lending money. The company's platform provides MAI Capital Management, Park Cities Asset Management, underestimated under-banked consumer loans and credit Victory Park Capital (Illinois), and other undisclosed investors on facilities to non-prime borrowers through assessment of July 25, 2018. This new capital will accelerate the company's credit risk using technology and advanced data science continued growth to reach individuals in need of and machine learning enabling consumers credit and loan straightforward, affordable loans. facilities as per their requirement and capability to payback. FinTech Acquisition II Operator of a blank check company. The company's The company (NASDAQ: FNTE) was acquired by International formation was facilitated for the purpose of effecting a Money Express, via its financial sponsor Stella Point Capital, merger, capital stock exchange, asset acquisition, stock through a reverse merger, resulting in the combined entity purchase, reorganization or the similar business trading on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange on July 26, 2018. combination. -

Report Authors

State of the Markets Inside views on the health and productivity of the innovation economy Second Quarter 2018 State of the Markets: Second Quarter 2018 4 Macro Snapshot: Long-Lived Bull Market 7 IPO Conditions: Value in the Face of Volatility 12 Late Stage: Another Round of Mega-Rounds 17 Global Perspective: Tension Over Tech 22 Special Report: Prepared for a Downturn? State of the Markets 2 State of the Markets: Second Quarter 2018 The Good Times Roll, Even as Risks Rise The bull market powers on, and money continues to flow into the innovation economy. At the same time, we are seeing a reemergence of volatility and a bevy of new risks — including tighter monetary policy and the specter of a trade war — but it’s still status quo for now in the capital markets. Despite market turbulence, the first quarter of 2018 ushered in several high-profile IPOs, and consumer- and enterprise businesses are finding success as public entities. Furthermore, companies reluctant to go down the IPO route found alternative paths. After years of successful fundraising, the world remains awash in capital, and sovereign wealth funds appear poised for even greater contributions. All of these factors are expected to provide further tailwinds for the tech sector. This remains an exciting time for tech around the globe, with some caveats. Innovation companies thrive on open markets, and rich valuations could be undermined by strained geopolitics, wavering consumer confidence and a releveling of investors’ portfolio mix as interest rates rise. While the good times roll, economic cycles don’t last forever, and the trends don’t always point upward. -

Q2 2018 Venture Capital Deals and Exits 3 July 2018

DOWNLOAD THE DATA PACK Q2 2018 VENTURE CAPITAL DEALS AND EXITS 3 JULY 2018 Fig. 1: Global Quarterly Venture Capital Deals*, Fig. 3: Number of Venture Capital Deals in Q2 2018 by Q1 2013 - Q2 2018 Fig. 2: Venture Capital Deals* in Q2 2018 by Region Investment Stage 4,500 80 100% Angel/Seed 7% 5% 1% 3% 4,000 2% 70 Aggregate Deal Value ($bn) 90% 1% 6% 3% Series A/Round 1 Other 1% 3% 3,500 60 80% 4% Series B/Round 2 3,000 50 70% 31% Israel 6% 2,500 54% 36% Series C/Round 3 60% 40 India 2,000 Series D/Round 4 and 50% No. of Deals 30 1,500 17% Later Greater China Growth 40% 16% 1,000 20 8% Capital/Expansion Proportion of Total Europe PIPE 500 10 30% 0 0 20% 37% North America Grant 31% Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 10% Venture Debt 30% 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 0% Add-on & Other No. of Deals Aggregate Deal Value ($bn) No. of Deals Aggregate Deal Value Source: Preqin Source: Preqin Source: Preqin Fig. 5: Average Value of Venture Capital Deals by Investment Fig. 4: Venture Capital Deals* in Q2 2018 by Industry Stage, 2016 - H1 2018 Fig. 6: Number of US Venture Capital Deals* in Q2 2018 by State 40% 37% 140 35% 120 115 117 104 30% 2016 100 California 25% 24% 23% 80 80 2017 20% 34% New York 36% 14% 15% 60 49 15% 13% 13% 41 Q1-Q2 12% Massachusetts 40 32 29 32 29 2018 Proportion Proportion of Total 9% 26 2828 28 10% 8% 16 22 5% 5% Average Deal Size ($mn) 20 1211 5% 4% 4% 4% Washington 2% 1% 3%2% 2% 2 2 2 0% 0 Illinois 4% Other Round 3 Round 1 Round 2 Series C/ Series Series A/ Series B/ Series 4% Internet Other IT Other Other Services Business Food & Related Telecoms 13% Angel/Seed Industrials Healthcare Agriculture Software & 9% Consumer Expansion Venture Debt Venture 4 and Later Discretionary Series D/Round Series Growth Capital/ No. -

The State of Growth Equity for Minority Business: a River of Capital Flowing Past Our Communities

The State of Growth Equity for Minority Business | 1 The State of Growth Equity for Minority Business: A river of capital flowing past our communities Marlene Orozco and Eutiquio “Tiq” Chapa The State of Growth Equity for Minority Business | 2 The NAIC (www.naicpe.com) was formed in 1971 as About this White Paper the American Association of MESBICs (AAMESBIC), Inc., under President Richard M. Nixon’s Black Capital- ism program, which sought to ease access to capital The National Association of Investment for diverse business. During the 1980s, AAMESBIC Companies, Inc. (NAIC) commissioned this report lobbied successfully for legislation that would allow alongside the report by Lawrence C. Manson, Jr., diverse firms to repurchase the preferred stock from “Access to Capital: Accelerating Growth of Diverse- the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) while and Women-Owned Businesses,” as part of a grant raising funds that were not SBA regulated. AAMESBIC from the Minority Business Development Agency firms began approaching pension funds and other (MBDA), an agency within the United States Depart- institutional investors to raise larger pools of capital. ment of Commerce. The grant seeks to facilitate the aggregation and deployment of $1 billion in growth In the next decade, the organization changed its name equity capital to ethnically Diverse- and Women- to the National Association of Investment Companies, Owned Business Enterprises (DWBEs). Inc. as most members had turned from reliance on the SBA to become independent, institutional private equi- ty firms. Today, the NAIC has a membership of more In this report, Marlene Orozco, Chief Executive Officer than 80 diverse private equity and hedge fund firms of Stratified Insights, LLC, a premier research managing more than $165 billion in assets.