219-Page Antitrust Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senator Hee Says UHM's Strategic Plan Has Room for Improvement

Inside Features 2,7 Sports 3 Thursday Editorials 4, 5 February 23, 2006 Comics 6 Surf 8 VOL. 100 | ISSUE 105 Serving the students of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa since 1922 WWW.KALEO.ORG ‘Date Movie’ Use the right is a gross board for the waste of time right conditions Features | Page 2 Surf | Page 8 Senator Hee says UHM’s Strategic SoJ plays Campus Center Plan has room for improvement By Alana Folen many different and complex arrays Konan told the committee that Ka Leo Contributing Writer of units that we have under our the university is on schedule with campus,” Konan said. “We have the time line put forth by the criti- At a recent informational brief- a very complicated university. We cal financial audit report of UHM ing, Sen. Clayton Hee, chair of the have many units. We are serving given to the legislature in Dec. Committee on Higher Education, many different functions, and to 2005 by the state auditor. In the criticized the University of Hawai‘i me there’s a great value in trying past year, Konan said the budget at Manoa’s Strategic Plan, saying to bring some simplicity to that. level summary has been reconfig- it was too brief and “needs to be And this plan has served a really ured to show data at the unit level, beefed up.” useful function – when I go to quarterly financial reports have “When you review the plan, meetings people do quote from the been posted on the Web to enhance it’s very broad,” Hee told UHM plan and there are parts of the plan the transparency of operations, interim Chancellor Denise Konan that really help to guide and moti- and a Campus Planning Day was and UH system-wide Chief vate members of my community.” hosted in October with 250 cam- Financial Officer Howard Todo. -

Child Pornography in the “Send Nudes” Era 239

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 2 Article 6 2020 Reevaluating Maryland’s Child Pornography Laws in the “Send Nudes” Era Shannon Hayden Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hayden, Shannon (2020) "Reevaluating Maryland’s Child Pornography Laws in the “Send Nudes” Era," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REEVALUATING MARYLAND’S CHILD PORNOGRAPHY LAWS IN THE “SEND NUDES” ERA Shannon Hayden* I. INTRODUCTION In 2018, A24 Films released the film Eighth Grade.1 Critics and audiences alike immediately praised the film for its “painfully real” depiction of what it is like to grow up in the age of social media.2 The film follows protagonist Kayla, a bit of a “quiet outcast,”3 as she navigates her way through the last week of middle school, trying desperately to fit in.4 Kayla’s middle school experience is similar to that of many adolescents; she is socially awkward at school and riddled with anxiety, but at home she comes alive, where she self- produces videos for her YouTube channel.5 Like many of her real life counterparts, Kayla has a crush on the resident cool kid Aiden, a classmate of hers.6 In one memorable scene, Kayla’s middle school is having an active shooter drill.7 During the drill, Kayla hears from * J.D. -

Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans

1 “Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans Ralph J. Poole “It’s Greek to whom?” In 2007-2008, a significant accumulation of cinematic and other visual media took up a celebrated episode of Greek antiquity recounting in different genres and styles the rise of the Spartans against the Persians. Amongst them are the documentary The Last Stand of the 300 (2007, David Padrusch), the film 300 (2007, Zack Snyder), the video game 300: March to Glory (2007, Collision Studios), the short film United 300 (2007, Andy Signore), and the comedy Meet the Spartans (2008, Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer). Why is the legend of the 300 Spartans so attractive for contemporary American cinema? A possible, if surprising account for the interest in this ancient theme stems from an economic perspective. Written at the dawn of the worldwide financial crisis, the fight of the 300 Spartans has served as point of reference for the serious loss of confidence in the banking system, but also in national politics in general. William Streeter of the ABA Banking Journal succinctly wonders about what robs bankers’ precious resting hours: What a fragile thing confidence is. Events of the past six months have seen it coalesce and evaporate several times. […] This is what keeps central bankers awake at night. But then that is their primary reason for being, because the workings of economies and, indeed, governments, hinge upon trust and confidence. […] With any group, whether it be 300 Spartans holding off a million Persians at Thermopylae or a group of central bankers trying to keep a global financial community from bolting, trust is a matter of individual decisions. -

Scary Movie 5 (2013) Una Parodia a Tutto Campo Che Si Avvale Dell'efficace Ritmo Della Versione Italiana

Scary Movie 5 (2013) Una parodia a tutto campo che si avvale dell'efficace ritmo della versione italiana. Un film di Malcolm D. Lee con Lindsay Lohan, Charlie Sheen, Terry Crews, Kate Walsh, Ashley Tisdale, Jerry O'Connell, Molly Shannon, Heather Locklear, Chris Elliott, Simon Rex. Genere Commedia durata 85 minuti. Produzione USA 2013. Uscita nelle sale: giovedì 18 aprile 2013 Tra rivisitazioni geniali e battute a doppio senso, nel quinto episodio della saga demenziale horror più amata i protagonisti del cinema sono nuovamente sostituiti dalla loro folle controfigura. Giancarlo Zappoli - www.mymovies.it Dopo che Charlie Sheen (che interpreta se stesso) è stato ucciso da un fantasma nella sua camera da letto in cui si stava dando da fare con Lindsay Lohan (anche lei nei propri succinti panni) i suoi tre figli vengono rapiti e ritrovati dopo qualche tempo in un'abitazione nel bosco. Sono affidati allo zio Dan e a sua moglie Jody ma ben presto appare chiaro che con loro è entrato nella casa anche uno spirito malvagio. Così sia il lavoro di Dan (che sta testando droghe sugli scimpanzé per sviluppare la loro intelligenza) che le aspirazioni di Jody di diventare l'etoile nel balletto in cui danza subiscono forti interferenze. Parodia. Il Dizionario della Lingua Italiana Sabatini Colletti a questa voce precisa: "Versione comica, caricaturale di un'opera letteraria, di una canzone, di un film". Dal lontano 2000 quando i Wayans, Jason Friedberg, Aaron Seltzer si divertirono a divertire il pubblico con sberleffi mirati ai film horror di successo dell'epoca, con cadenza regolare la parodia dei blockbuster non solo orrorifici ha i suoi appassionati fan. -

PDF of Credits

ALANA DA FONSECA EXECUTIVE MUSIC PRODUCER – SONGWRITER MOTION PICTURES EUROVISION (Music Producer, Vocal Arranger) David Dobkin, dir. Netflix THE ADDAMS FAMILY (Music Producer) Greg Tiernan, Conrad Vernon, dirs. MGM GOOD BOYS (Executive Music Producer) Gene Stupnitsky, dir. Universal Pictures PITCH PERFECT 3 (Executive Music Producer) Trish Sie, dir. Universal Pictures POMS (Executive Music Producer) Zara Hayes, dir. STX ISN’T IT ROMANTIC (Music Producer) Todd Strauss-Schulson, dir. Warner Bros. THE SECRET LIFE OF PETS (Producer “We Go Together”) Chris Renaud, dir. Universal Pictures PITCH PERFECT 2 (Arranger/Vocal Arranger) Elizabeth Banks, dir. Universal Pictures ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP (Executive Music Producer) Walt Becker, dir. Fox 2000 PITCH PERFECT (Additional Vocal Arranger) Jason Moore, dir. Universal Pictures HANNAH MONTANA: THE MOVIE (Producer “Let’s Do This”) Peter Chelsom dir. Walt Disney Studios 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 ALANA DA FONSECA EXECUTIVE MUSIC PRODUCER – SONGWRITER TELEVISION JULIE AND THE PHANTOMS (Vocal Arranger/Vocal Producer, Songwriter) Kenny Ortega, dir. Netflix TROLLS: THE BEAT GOES ON (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) Hannah Friedman, creator Netflix DWA UNNANOUNCED SHOW (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) DreamWorks Animation ALVINNN!!! AND THE CHIPMUNKS (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) Janice Karman, creator Nickelodeon LIVE SHOW TROLLS LIVE TOURING SHOW (Music Producer) SONGWRITER NAKED (Writer “Nobody But You”) Michael Tiddes, dir. Netflix STAR (TV) (Writer “Honeysuckle”) Lee Daniels, Tom Donaghy, creators Fox ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP (Writer “Home”) Walt Becker, dir. Fox 2000 POWER (TV) (Writer “Old Flame”) Courtney A. Kemp, creator Starz FIFTY SHADES OF GREY (Writer “Awakening”) Sam Taylor-Johnson, dir. -

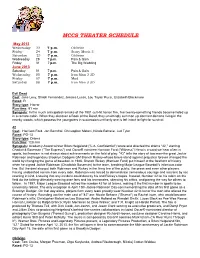

Mccs Theater Schedule

MCCS THEATER SCHEDULE May 2013 Wednesday 22 7 p.m. Oblivion Friday 24 7 p.m. Scary Movie 5 Saturday 25 7 p.m. Oblivion Wednesday 29 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Friday 31 7 p.m. The Big Wedding June 2013 Saturday 01 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Wednesday 05 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Friday 07 7 p.m. Mud Saturday 08 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Evil Dead Cast: Jane Levy, Shiloh Fernandez, Jessica Lucas, Lou Taylor Pucci, Elizabeth Blackmore Rated: R Story type: Horror Run time: 91 min Synopsis: In the much anticipated remake of the 1981 cult-hit horror film, five twenty-something friends become holed up in a remote cabin. When they discover a Book of the Dead, they unwittingly summon up dormant demons living in the nearby woods, which possess the youngsters in succession until only one is left intact to fight for survival. 42 Cast: Harrison Ford, Jon Bernthal, Christopher Meloni, Nicole Beharie, Jud Tylor Rated: PG-13 Story type: Drama Run time: 128 min Synopsis: Academy Award winner Brian Helgeland ("L.A. Confidential") wrote and directed the drama "42," starring Chadwick Boseman ("The Express") and OscarR nominee Harrison Ford ("Witness").Hero is a word we hear often in sports, but heroism is not always about achievements on the field of play. "42" tells the story of two men-the great Jackie Robinson and legendary Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey-whose brave stand against prejudice forever changed the world by changing the game of baseball. In 1946, Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford) put himself at the forefront of history when he signed Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) to the team, breaking Major League Baseball's infamous color line. -

Newsletter 02/16 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 02/16 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 354 - Februar 2016 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 02/16 (Nr. 354) Februar 2016 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Kennen Sie den Mann auf dem Titel- bild? Nein? Aber bestimmt kennen Sie ein paar seiner Filme. Denn Christian Duguay hat schon einige handfeste Action-Filme inszeniert, wie beispiels- Eine kurze Information an alle Cinera- Zu guter Letzt möchten wir gerne noch weise THE ART OF WAR, ma-Fans, die ungeduldig auf die noch Ihren Blick auf die nächste Seite len- HYDROTOXIN oder SCREAMERS. fehlenden beiden Titel CINERAMA’S ken. Denn dort spricht unsere Kolum- Vor zwei Wochen hatten wir Gelegen- RUSSIAN ADVENTURE und THE nistin Anna wieder einmal mit Holly- heit, uns mit dem gebürtigen Kanadier BEST OF CINERAMA warten. Flicker wood. Ihre Kolumne steht dabei dieses in Stuttgart zu unterhalten. Denn ge- Alley wird diese beiden DVD/BD- Mal ganz im Zeichen des Valentinstags. nau dort stellte der renommiere Regis- Releases nicht vor Herbst veröffentli- Wir haben uns jedenfalls beim Lesen seur seinen neuesten Film, den packen- chen. Hauptgrund dafür ist die schöne des Textes großartig amüsiert. Und den Abenteuerfilm SEBASTIAN UND Tatsache, dass man bei RUSSIAN jetzt Sie dran! DIE FEUERRETTER, dem begeisterten ADVENTURE unverhofft auf die Publikum persönlich vor. Natürlich hat- Originalnegative gestoßen ist und sich Ihr Laser Hotline Team ten wir wieder unsere Kamera vor Ort Experte David Strohmaier der besseren und haben das alles für Sie in Bild und Qualität wegen für eine komplette Ton festgehalten. -

Broadcast Live on Pop and Hosted by Tyra Banks

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES WINNERS FOR THE 42nd ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Broadcast Live on Pop and Hosted by Tyra Banks Betty White Honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award Burbank, CA – April 26, 2015 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) tonight announced the winners of the 42nd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards in a sold-out gala for over 1,200 attendees held at Stage 16 of the historic Warner Bros. Studios Lot in Burbank, CA. The awards presentation was broadcast live on Pop at 8 p.m. EDT/5 p.m. PDT. “What an eclectic mix of the magnificent bounty that is Daytime Television,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “So many stars lighting up the red carpet at the iconic Warner Bros. Studio Lot in addition to the indefatigable, unparalleled Betty White as our Lifetime Achievement Award honoree. This is a terrific showcase of the power of Daytime Television that will be remembered for years to come!” Tonight’s telecast was hosted by Tyra Banks and included an over-flowing lineup of television talent including Regis Philbin, Steve Harvey, Marie Osmond, Craig Ferguson, Deidre Hall, Nancy O’Dell, Shemar Moore and Alex Trebek. Also presenting are cast members from the four daytime soaps, including Daniel Goddard, Justin Hartley and Melissa Claire Egan of “The Young and The Restless,” Kirsten Storms and Ryan Paevey of “General Hospital,” Christopher Sean, Freddie Smith and Guy Wilson of “Days of Our Lives” and Jacob Young, Karla Mosley and Linsey Godfrey of “The Bold and the Beautiful.” In addition, there were special appearances by Mario Lopez, Tom Bergeron, Leeza Gibbons, Chrissy Teigen, Alan Thicke, Kevin Frazier, Vicki Lawrence, Eileen 1 Davidson and Julie Chen, Sara Gilbert, Sharon Osbourne, Aisha Tyler and Sheryl Underwood, all of “The Talk.” The 42nd Annual Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast during the 2014 calendar year. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

Allusion As a Cinematic Device

I’VE SEEN THIS ALL BEFORE: ALLUSION AS A CINEMATIC DEVICE by BRYCE EMANUEL THOMPSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Bryce Thompson for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2019 Title: I’ve Seen this All Before: Allusion as a Cinematic Device Approved: _______________________________________ Daniel Gómez Steinhart Scholarship concerning allusion as a cinematic device is practically non- existent, however, the prevalence of the device within the medium is quite abundant. In light of this, this study seeks to understand allusion on its own terms, exploring its adaptation to cinema. Through a survey of the effective qualities of allusion, a taxonomy of allusionary types, film theory, and allusion’s application in independent cinema, it is apparent that allusion excels within the cinematic form and demonstrates the great versatility and maximalist nature of the discipline. With the groundwork laid out by this study, hopefully further scholarship will develop on the topic of allusion in order to properly understand such a pervasive and complex tool. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis committee of Professor Daniel Steinhart, Professor Casey Shoop, and Professor Allison McGuffie for their continued support, mentorship, and patience. I would also like to thank Professor Louise Bishop who has been immensely helpful in my time at university and in my research. I have only the most overwhelming gratitude towards these gracious teachers who were willing to guide me through this strenuous but rewarding process, as I explore the maddening and inexact world of allusion. -

At 625 First & Oxford

First Nations Studies agreement signed 4 Movember: Month of mighty Mos 5 The threat of international terrorism 6 Falcons receive OCAA honours 22 Volume 47 Issue No. 11 November 3, 2014 theinterrobang.ca At 625 First & Oxford Name this Building CONTEST OCT 1 - NOV 30 Win ONE year FREE rent enter at adamasgroup.ca SPORTS&LEISURE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR OPINION [email protected] NEWS 2 INTERACTIVE Volume 47 Issue No. 11 November 3, 2014 theinterrobang.ca LI#FESTFSUYLInterrobangES @apurvpatre @nachiket_k @nachiket_k SPORTS&LEISURE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR OPINION [email protected] Share your pictures on Instragram using #FSUInterrobang† ‡ for a chance to win FREE LUNCH at the or NEWS! †TERMS & CONDITIONS: Submit your original photos on Instagram with the designated #FSUInterrobang hashtag to have a chance to be printed in next week’s issue. By including the hashtag, you agree that we may print your photo and that your photo does NOT contain: (a) copyrighted works (other than owned by you); (b) contain vulgar, pornographic, obscene or indecent behaviour or images; (c) defame or libel any third party; (d) been licensed; or (e) contain any watermarks or other notices, whether digital or otherwise obstructing the Photo Entry. Photo entries that do not comply with these Terms & Conditions or that otherwise contain prohibited or inappropriate content as determined by Interrobang Staff, in its sole discretion, will not be shared. ‡FREE LUNCH: Contest only open to full-time Fanshawe College students. Offer consists of a $10 gift card, given out monthly, that can only be redeemed at Oasis or The Out Back Shack during business hours at Fanshawe College in London, Ontario. -

Virtual Prostitution: New Technologies and the World's Oldest Profession David Cardiff

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 18 | Number 4 Article 6 1-1-1996 Virtual Prostitution: New Technologies and the World's Oldest Profession David Cardiff Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation David Cardiff, Virtual Prostitution: New Technologies and the World's Oldest Profession, 18 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 869 (1996). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol18/iss4/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Virtual Prostitution: New Technologies and the World's Oldest Profession by DAVID CARDIFF* Table of Contents I. Outline of the New Technologies .......................................... 874 II. A Brief History of the Laws Relating to Pornography ....... 877 A . Pornography in G eneral ................................................... 877 B . D ial-a-Porn C ases .............................................................. 882 C. Pornography as Prostitution Cases .................................. 887 III. Arguments For and Against Aggressive Porn R egulation ...............................................................................