Forest Management in Bang Est Management in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Research on Farm Adld Village Forestry

Collaborative Research on Farm aDLd Village Forestry Organizers: ForestryIFuelwood Research and Development (FIFRED) Project International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development The Forestry IFuelwood Research and Development (FI FRED) Project is designed to help scientists aLlLlress the neeLls of small-scale farmers in the L1e.eloping world for fuel wood and other tree products. Funded by the U.S. Agency !I)r Interna tional Development. the project provides a network through which scientists exchange research plans. methods. and resuits. Research and development activities center on the production and use of trees that meet the several household needs of small farmers. FIFRED is implemented by the Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Development. a private. non-profit U.S. organization working in agricultural development around th'~ worlLl. It was established in 1985 through the merging of the Agricultural Development Council. the International Agricultural Development Servile. and the Winrock International Livestock Research and Training Center. Winrock's mission is to reduce hunger and poverty in the world through sustainable agricultural and rural development. Winrock helps ~cople of developing areas to strengthen their agricultural research anLl extension systems. develop their human resources. institute appropriate food and agricultUi al policies. manage their renewahle resources. and improve their agricultural production systems. .. Collaborative Research on Farm and Village Forestry Report of a workshop held April 23-25, 1988 in Kathmandu, Nepal Editors: David A. Taylor and Charles B. Mehl Workshop co-sponsors: Forestry/Fuelwood Research and Development (FIFRED) Project International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development .. International Development Research Centre Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Nepal 1988 Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Development ... -

Indian Social Forest: Proportions and Groups

|| Volume 6 || Issue 1 || January 2021 || ISO 3297:2007 Certified ISSN (Online) 2456-3293 INDIAN SOCIAL FOREST: PROPORTIONS AND GROUPS Dr. Mohd Sadiq Ali Khan Principal, School Education, Sanskriti University, Mathura, India ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Abstract: The forests are a highly appreciated ecological commodity that, under proper governance, can be fruitful and beneficial. The biggest, more diverse and self-generating forests of all ecosystems. Forests affect diverse factors including the climate, flora, fauna and civilization directly and effectively. They serve as buffer states among habitats created by natural or human beings. Forests also helped the human race over the years. The growing population of humans and animals has, however, resulted in unconscious agricultural use of forestry. This has contributed to a dramatic reduction in forest wealth in India in the last few years. The forest logging proceeded unregulated until the mid-1970s, contributing to the detrimental consequences of deforestation. This included soil erosion, flickering storms, lack of water, timber and fodder, the disappearance of important flora and fauna and global warming. The Indian government Launched a social forest project in 1976 to eliminate the pressure on current forestry by plants in all vacancies and fallow lands. This project was introduced in 1976 by the National Commission on Agriculture. The goal of this paper is to gain insight into the significance and components of Indian social forestry. It also aims to define social forestry forms and advantages and to evaluate some research studies in order to encourage social forestry in India. Keywords: Forest, India, Environment, Social, Agriculture, government -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I INTRODUCTION vegetation. Owing to the overgrazing of cattle, community pastures are worsening. -

References – for All Case Studies and Overview

Changing Ownership and Management of State Forest Plantations. References References – for all case studies and overview ABARE (2001). Australian Commodity Statistics 2001. Canberra. ACF (1988). The wood and the trees revisited. ACF responds to the forest industries. ACF, Hawthorn, Victoria. Acuiti Legal (2002). Tax concessions reintroduced for plantation forestry industry. www.ptaa.com.au/acuiti.html Accessed 30/04/2002. AFFA (Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry – Australia) (2002). Industry Development and Adjustment. Australia’s Unique Forests. www.affa.gov.au/ Accessed 31/07/2002 Afforestation Proprietary Limited. 1926. Timber wealth, something for all: a large return for a small investment. Afforestation Proprietary Ltd, Melbourne. 22p. Aldwell, P.H.B. 1984. Some social and economic implications of large-scale forestry in Waiapu County. Forest Research Institute, New Zealand Forest Service, Rotorua. 39p. Alexander, F. Brittle, S., Ha, A.G. Leeson, T. and Riley,C. (2000). Landcare and farm forestry: providing a basis for better resource management on Australian farms. ABARE report to the Natural Heritage Trust, Canberra. Anderson, J. (1997). Minister removes export controls on wood sourced from plantations in Western Australia. Media Release Department for Primary Industries and Energy, 22nd September 1997. Anderson, R.S. and W. Huber. 1988. The Hour of the Fox: Tropical Forests, The World Bank and Indigenous People in Central India. New Delhi: Vistaar/Sage. Anon. (2001). Gunns adds North Forest to its trees. The Australian March 20th 2001. Anon. 1996. NZ government rushes to sell forests. Green Left Weekly. URL: www.greenleft.org.au/back/1996/245/245p18.htm Accessed 28/11/2002 Anon. 1998. Job cuts decimate New Zealand forestry industry. -

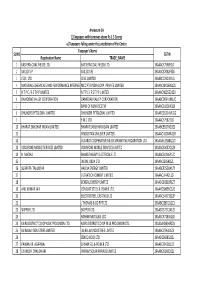

List of the Selected Students Under AICTE-Pragati Scholarship Scheme (Diploma) 2020-21

List of the Selected Students under AICTE-Pragati Scholarship Scheme (Diploma) 2020-21 S.No. Institute_State/ UT Application_ID Applicant_Name Institution_Name AISHE_Code Institute_Address 1 ANDAMAN AND AN202021011795780 POOJA BISWAS Dr.B.R. Ambedkar C-6528 Pahargaon, Junglighat Post office Pin 744103, South NICOBAR Institute of Technology Andaman District, Port Blair. (Id: C-6528) 2 ANDAMAN AND AN202021011566460 J DIVYA RANI Dr.B.R. Ambedkar C-6528 Pahargaon, Junglighat Post office Pin 744103, South NICOBAR Institute of Technology Andaman District, Port Blair. (Id: C-6528) 3 ANDAMAN AND AN202021011113799 P SAVITHRI Dr.B.R. Ambedkar C-6528 Pahargaon, Junglighat Post office Pin 744103, South NICOBAR Institute of Technology Andaman District, Port Blair. (Id: C-6528) 4 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021012111782 ANNURU NEEHARIKA SRI PADMAVATHI S-644 NEAR SV DAIRY FORM, SV UNIVERSITY ROAD, TIRUPATI WOMENS POLYTECHNIC 5 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021012009522 KUSUMURU SUMITRA GOVERNMENT S-15368 GOVERNMENT POLYTECHNIC, M.R.NAGAR, POLYTECHNIC PARVATHIPURAM ,VIZIANAGARAM DISTRICT, ANDHRA PARVATHIPURAM PRADESH- 535 522 6 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021012109572 KOMMU SUSMITHA SRI PADMAVATHI S-644 NEAR SV DAIRY FORM, SV UNIVERSITY ROAD, TIRUPATI WOMENS POLYTECHNIC 7 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021012110923 LAFFREY VARSHA SRI PADMAVATHI S-644 NEAR SV DAIRY FORM, SV UNIVERSITY ROAD, TIRUPATI REBECCA WOMENS POLYTECHNIC 8 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021011488570 MALIREDDY NIRMALA Prasanthi Polytechnic S-15804 PUDIMADAKA ROAD, ATCHUTAPURAM 9 ANDHRA PRADESH AP202021011641515 SIVALANKA BHAGYA -

Social Forestry: a Tool for Improving Livelihood of Rural People

A SEMINAR PAPER ON SOCIAL FORESTRY: A TOOL FOR IMPROVING LIVELIHOOD OF RURAL PEOPLE Course Title: Seminar Course Code: AFE 598 Summer’18 SUBMITTED TO: Course Instructors Major Professor 1. Dr. Md. Mizanur Rahman Dr. Md. Abiar Rahman Professor, BSMRAU Professor, BSMRAU 2. Dr. A. K. M. Aminul Islam Dept. of Agroforestry & Environment Professor, BSMRAU 3. Dr. Md. Rafiqul Islam Professor, BSMRAU 4. Dr. Dinesh Chandra Shaha Assistant Professor, BSMRAU SUBMITTED BY: Zannatul Ferdaous Bony MS Student Reg. No.: 13-05-2992 Department of Agroforestry & Environment BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIBUR RAHMAN AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY SALNA, GAZIPUR 1706 1 | P a g e Social Forestry- A Tool for Improving Livelihood of Rural People1 Zannatul Ferdaous Bony2 Abstract In many countries around the world, people living in rural areas have lower incomes and are generally less prosperous than their urban counterparts. Because of this, governments often attempt to promote rural development through the development of natural resources such as forests. Policies in developed countries tend to focus on increasing income and employment, whereas in developing countries rural development often has to meet more basic needs. However, when broader social and environmental considerations are taken into account, forests are considerably more important for rural communities. The utilization of forest resources could generate significant revenues for governments that could be used for rural development. A number of developing countries have implemented forest polices that aim to help rural communities. Examples include: Betagi and Pomra Community Forestry Project in Bangladesh; Joint Forest Management in India; Master Plan for Forestry Sector in Nepal; Promotion of Social Forestry and Rain Water Conservation Technology in Pakistan etc. -

Application No Rank

Application No Rank Candidate Name DOB Category Gender Email Mobile Address CHATRIWALI DHANI,MAHESHWARA ROAD IMUCET1422876 9509 RAJKUMAR MEENA 12-Jul-97 ST Male [email protected] 9950227724 DAUSA,DIST - DAUSA,Dausa-303303,Rajasthan VPO - KODYAI,TEH - BONLI,DIST - SAWAI IMUCET1418796 9503 OMPRAKASH MEENA 01-Aug-97 ST Male [email protected] 8696182466 MADHOPUR,Sawai Madhopur-322030,Rajasthan GANESH PUR,RAHMANPUR,CHINHAT IMUCET1413647 9501 MANISH KUMAR 20-Jul-97 SC Male [email protected] 7897989249 LUCKNOW,Lucknow-226028,Uttar Pradesh C-10 AKASHVANI COLONY,SECTOR-8 IMUCET1414405 9493 ANIVEH KUMAR 04-Jan-98 ST Male [email protected] 7408050958 OBRA,SONEBHADRA,Sonbhadra-231219,Uttar Pradesh VILL- POWER GANJ,GANESH RICE MILL PO- ANAITH,PS- IMUCET1422429 9483 ABHYMANU KUMAR 10-Aug-96 SC Male [email protected] 8521670288 * ARA NAWADA,Bhojpur-802301,Bihar 171,PURWA DIN DAYAL,ROORKEE,Rorkee- IMUCET1420839 9467 SACHIN 07-Apr-98 SC Male [email protected] 8439150233 247667,Uttarakhand V.P.O. UPPER LAMBA GAON,TEH. JAISINGHPUR,DISTT. IMUCET1416967 9447 SHUBHAM SONI 04-Nov-96 SC Male [email protected] 9736872264 KANGRA H.P.,Kangra-176096,Himachal Pradesh 007/75-B,EDENWALA CHAWL,J B MARG ELPHINSTONE IMUCET1408099 9448 DASHANKIT DATTATRAY LONDHE 04-Jan-97 SC Male [email protected] 8097948424 ROAD,Mumbai City-400025,Maharashtra E-L 3, SICHAI VIBHAG,,GOMTI BAIRAJ COLONY,BALOO IMUCET1420036 9453 SAURABH KUMAR 31-Dec-96 SC Male [email protected] 8115783483 ADDA,Lucknow-226001,Uttar Pradesh AT-KALYANPUR,PO-KALYANPUR,PS-BIDUPUR,DIST- -

Lessons Learned from Community Forestry in Asia and Their Relevance for Redd+ Forest Carbon, Markets and Communities (Fcmc) Program

LESSONS LEARNED FROM COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN ASIA AND THEIR RELEVANCE FOR REDD+ FOREST CARBON, MARKETS AND COMMUNITIES (FCMC) PROGRAM FEBRUARY 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by FCMC. This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development by Tetra Tech, through a Task Order under the Prosperity, Livelihoods, and Conserving Ecosystems (PLACE) Indefinite Quantity Contract Core Task Order (USAID Contract No. EPP-I-00-06-00008-00, Order Number AID-OAA-TO-11-00022). This report was prepared by: Tetra Tech 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, Vermont 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 Email: [email protected] www.tetratechintdev.com Forest Carbon, Markets and Communities Program (FCMC) 1611 North Kent Street, Suite 805 Arlington, VA 22209 Tel: (703) 592-6388 Scott Hajost, Chief of Party Email: [email protected] Ian Deshmukh, Senior Technical Advisor/Manager Email: [email protected] Olaf Zerbock, USAID Contracting Officer’s Representative Email: [email protected] For more information regarding this study, contact: Paula J. Williams, FCMC Social and Environmental Soundness Task Lead Email: [email protected] This report is one of four reports on “Lessons Learned from Community Forestry and Their Relevance for REDD+.” The series comprises three regional reviews on this topic, prepared for Latin America (by Janis Alcorn), Africa (by Tom Blomley) and Asia (by Robert Fisher). The global synthesis of the three regional reviews was prepared by Roy Hagen. Paula J. Williams has managed and served as the overall editor for the three regional reviews and a global synthesis. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

Guidelines on Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry

178 178 FAO FORESTRY PAPER Guidelines on urban and Guidelines on urban and peri-urban forestry peri-urban forestry Although cities occupy only 2 percent of the planet’s surface, their inhabitants use 75 percent of its natural resources; by 2050, 70 percent of the global population will live in cities and towns. Sustainable urban development is crucial, therefore, for ensuring the quality of life of the world’s people. Forests and trees in cities, if properly managed, can make Guidelines on urban and peri-urban forestry important contributions to the planning, design and management of sustainable, resilient urban landscapes. They can help make cities more pleasant, attractive and healthy places in which to live, as well as safer, wealthier and more diverse. A few years ago, FAO initiated a collaborative process to develop voluntary guidelines aimed at optimizing the contributions of forests and trees to sustainable urban development. Scientists, practitioners and public administrators from cities worldwide were brought together to discuss the elements and key challenges of urban forestry, and a smaller team of experts was assembled to distil this vast knowledge. This document is the ultimate result of that process. Intended for a global audience comprising urban decision-makers, civil servants, policy advisors and other stakeholders, it will assist in the development of urban and peri-urban forests that help meet the present and future needs of cities for forest products and ecosystem services. These guidelines will also help increase community awareness of the contributions that forests and trees can make to improving quality of life, and of their essential role in global sustainability. -

Forty Years of Community-Based Forestry

176 176 FAO FORESTRY PAPER Forty years of Forty years of community-based forestry community-based forestry Forty years of community-based forestry – A review its extent and effectiveness A review of its extent and effectiveness A review of its extent and effectiveness Since the 1970s and 1980s, community-based forestry has grown in popularity, based on the concept that local communities, when granted sufcient property rights over local forest commons, can organize autonomously and develop local institutions to regulate the use of natural resources and manage them sustainably. Over time, various forms of community-based forestry have evolved in different countries, but all have at their heart the notion of some level of participation by smallholders and community groups in planning and implementation. This publication is FAO’s rst comprehensive look at the impact of community-based forestry since previous reviews in 1991 and 2001. It considers both collaborative regimes (forestry practised on land with formal communal tenure requiring collective action) and smallholder forestry (on land that is generally privately owned). The publication examines the extent of community-based forestry globally and regionally and assesses its effectiveness in delivering on key biophysical and socioeconomic outcomes, i.e. moving towards sustainable forest management and improving local livelihoods. The report is targeted at policy-makers, practitioners, researchers, communities and civil society. ISSN 0258-6150 ISBN 978-92-5-109095-4 ISSN 0258-6150 FAO FORESTRY -

Indian March from Forestry and Agrobased Traditional Knowledge to Industry Based Pharma Industry

Asian J. of Bio Sci. (2006) Vol. 1 No. 2 : 70-73 70 Indian march from forestry and agrobased traditional knowledge to industry based pharma industry Lokendra Singh* and Preeti Vats Department of Botany, Meerut College, Meerut - 250 004 (U.P.) India (Accepted : March, 2006) Agroforestry was born as a branch of forestry in 1960 at FRI, Dehradun to optimize production and economic returns per unit area in lieu of sustainable development besides meeting the social, cultural, religious, spiritual needs of human beings and maintain ecological equilibrium of the biome. Along with social forestry, farm forestry, organic farming and herbal gardens, agroforestry is also the answer to the good and technique based raw materials to the Pharma industry and alternative therapies such as Ayurvedic, Unani, Sidha, Homeopathy and Tibetan traditional system to meet the needs of domestic medicinal markets and as an export earner. Key words: Traditional knowledge, Agroforestry, Medicinal wealth, Pharma industry. INTRODUCTION main thrust on “Biodiversity conservation (BDC) and Joint Forest S megabiodiversity centre of the world, India is a hotspot Management (JFM)” aimed at benefiting both the local people as for a variety of forests having 8 distinct floristic regions and well as country at large. Along with Social Forestry, Urban 16A main natural formations with several subtypes (Aren, 2002). Forestry, Farm Forestry was launched in the late 1970 with the Despite a forest policy which dates back to 1894, rising human main focus on planting trees by government on village lands and and cattle population, deforestation, forest fires, denudation, uncultivated lands (BISR, 1986; Chaturvedi, 1979; FAO, 1988; shifting cultivation, commercial exploitation of flora and biopiracy, Bhattcharya, 1990; Tiwari, 1991; Saxena, 1996) to improve the placed forests under constant pressure, necessitating biological productivity and economic return of the same piece of comprehensive and holistic forest policy with priorities of efficient land. -

Into Forestry?

Forest Policy and Environment Programme: Grey Literature Putting ‘social’ into forestry? November 2005 Mary Hobley Jack Westoby’s challenge to the forestry world that ‘forestry is not about trees, it is about people. And it is about trees only insofar as trees can serve the needs of people’ (Westoby, 1967 cited in Leslie, 1987: ix) was first answered by social forestry. Its appearance on the international stage was as a response to the so-called poor-man’s fuelwood energy crisis, the supposed eco-disasters of the 1970s and most importantly the growing realisation that industrial forestry was failing to deliver the claimed socio-economic benefits. All of this was to have profound consequences on the future shape of the forest sector. The history of these changes is an important part of understanding why and how social forestry evolved. The post-war period from the mid 1940s to the late 1960s was a period of increasing prosperity, rapid industrialisation and full employment within the core countries of the Western world. Modernisation theories permeated all sectors, including forestry. Westoby in a seminal paper of 1962 advanced the argument that industrial forestry would stimulate development in underdeveloped countries (Westoby, 1962). He held that forest-based industries had strong forward and backward linkages with the rest of the economy because they furnished a wide range of goods and services and used mainly local inputs. The demand for forest products was forecast to rise rapidly following the rapid industrialisation of all economies. These arguments provided the basis for forest policy development in both developed and less developed countries.