Building Beaches Branch, Toronto Public Library, 1910-1916 Barbara Myrvold, Local History Services Specialist, Toronto Public Library Revised September 26, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward City Charters in Canada

Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 34 Toronto v Ontario: Implications for Canadian Local Democracy Guest Editors: Alexandra Flynn & Mariana Article 8 Valverde 2021 Toward City Charters in Canada John Sewell Chartercitytoronto.ca Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp Part of the Law Commons Citation Information Sewell, John. "Toward City Charters in Canada." Journal of Law and Social Policy 34. (2021): 134-164. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol34/iss1/8 This Voices and Perspectives is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Sewell: Toward City Charters in Canada Toward City Charters in Canada JOHN SEWELL FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS, there has been discussion about how cities in Canada can gain more authority and the freedom, powers, and resources necessary to govern their own affairs. The problem goes back to the time of Confederation in 1867, when eighty per cent of Canadians lived in rural areas. Powerful provinces were needed to unite the large, sparsely populated countryside, to pool resources, and to provide good government. Toronto had already become a city in 1834 with a democratically elected government, but its 50,000 people were only around three per cent of Ontario’s 1.6 million. Confederation negotiations did not even consider the idea of conferring governmental power to Toronto or other municipalities, dividing it instead solely between the soon-to-be provinces and the new central government. -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Wychwood Park Wychwood Park Sits on a Height of Land That Was Once the Lake Iroquois Shore

Wychwood Park Wychwood Park sits on a height of land that was once the Lake Iroquois shore. The source for Taddle Creek lies to the north and provides the water for the pond found in the centre of the Park. Today, Taddle Creek continues under Davenport Road at the base of the escarpment and flows like an underground snake towards the Gooderham and Worts site and into Lake Ontario. Access to this little known natural area of Toronto is by two entrances one at the south, where a gate prevents though traffic, and the other entrance at the north end, off Tyrell Avenue, which provides the regular vehicular entrance and exit. A pedestrian entrance is found between 77 and 81 Alcina Avenue. Wychwood Park was founded by Marmaduke Matthews and Alexander Jardine in the third quarter of the 19th century. In 1874, Matthews, a land- scape painter, built the first house in the Park (6 Wychwood Park) which he named “Wychwood,” after Wychwood Forest near his home in England. The second home in Wychwood Park, “Braemore,” was built by Jardine a few years later (No. 22). When the Park was formally established in 1891, the deed provided building standards and restrictions on use. For instance, no commercial activities were permitted, there were to be no row houses, and houses must cost not less than $3,000. By 1905, other artists were moving to the Park. Among the early occupants were the artist George A. Reid (Uplands Cottage at No. 81) and the architect Eden Smith (No. 5). Smith designed both 5 and 81, as well as a number of others, all in variations of the Arts and Crafts style promoted by C.F.A. -

First Report 1967-1969

I FIRST REPORT 1967-1969 METROPOLITAN TORONTO LIBRARY BOARD FIRST REPORT, 1967-1969 of the Metropolitan Toronto Library Board THE BOARD Chairman: T. H. GOUDGE Members: JOHN M. BENNETT, M.A., Ph.D. CONTROLLER MARGARET CAMPBELL, Q.C. CARL W. CASKEY WALTER G. CASSELS, Q.C. C. DOUGLAS CUTHBERT HER WORSHIP, THE MAYOR OF EAST YORK, MISS TRUE DAVIDSON MRS. G. 0. MORGAN HARVEY L. MOTT Director: JOHN T. PARKHILL, M.A., B.L.S. Secretary- Treasurer: ANTHONY H. WINFIELD, CG.A. The Metropolitan Toronto Library Board was set up as a regional library board under the Public Libraries Act, 1966 and the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto Amendment Act, 1966. It is composed of one person appointed by each of the six area Members of the Board who resigned during the three-year period: municipalities; the chairman of the Metropolitan Council, or his representative; one person appointed KEELE S. GREGORY (1967) by the Metropolitan Toronto School Board; and one person appointed by the Metropolitan Separate CHARLES L. CACCIA, M.P. (1968) School Board. Members of the Board are appointed for a three-year term. R. C. STONE (1969) REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN A writer about books has stated that "those works are most valuable that set our thinking faculties in the fullest operation." Many such works are contained in the historic Central Collections which had been brought together over the years by the Toronto Public Library. Never before have so many people sought out the rich resources of these collections and it is a matter of some significance that this growing interest has increased during the first full year of their operation by the Metro Board. -

COVID-19 Emergency Response

STAFF REPORT 14. INFORMATION ONLY COVID-19 Emergency Response Date: April 27, 2020 To: Toronto Public Library Board From: City Librarian SUMMARY The purpose of this report to update the Toronto Public Library Board on Toronto Public Library’s (TPL’s) operations, services and responses to the COVID-19 public health emergency, and its integration with City of Toronto’s Incident Management System. TPL’s pandemic plan has been developed in accordance with the best practices of emergency management and business continuity, and in alignment with the City of Toronto planning, including the Toronto Public Health Plan for a Pandemic, and the City of Toronto Pandemic Integrated Corporate Response Plan. TPL’ s Pandemic Response Plan and the emergency response structure are provided in Attachments 1, 2 and 3. FINANCIAL IMPACT The emergency shut down of branches at the end of day on March 13 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic will significantly impact TPL’s operating and capital budgets in a number of ways. Immediately following the shutdown, there were additional operating cost pressures, including the loss revenues from fines, printing and facility rentals. Some operating budget reliefs being experienced include savings in guard services, utilities, staff printing and office supplies. All staff continue to be paid. There are also additional costs being incurred related to setting up a remote workforce. Overall, for the first month of the shutdown, TPL estimates that there is a net operating budget pressure of nearly $1 million. As the shutdown continues, it is expected that lost revenues will continue, and additional savings will be realized for the operating budget, and this will be monitored and reported to the Board and City. -

Renaming to the Toronto Zoo Road

Councillor Paul Ainslie Constituency Office, Toronto City Hall Toronto City Council Scarborough Civic Centre 100 Queen Street West Scarborough East - Ward 43 150 Borough Drive Suite C52 Scarborough, Ontario M1P 4N7 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Chair, Government Management Committee Tel: 416-396-7222 Tel: 416-392-4008 Fax: 416-392-4006 Website: www.paulainslie.com Email: [email protected] Date: October 27, 2016 To: Chair, Councillor Chin Lee and Scarborough Community Council Members Re: Meadowvale Road Renaming between Highway 401 and Old Finch Road Avenue Recommendation: 1. Scarborough Community Council request the Director, Engineering Support Services & Construction Services and the Technical Services Division begin the process to review options for the renaming of Meadowvale Road between Highway 401 and Old Finch Avenue including those of a "honourary" nature. 2. Staff to report back to the February 2017 meeting The Toronto Zoo is the largest zoo in Canada attracting thousands of visitors annually becoming a landmark location in our City. Home to over 5,000 animals it is situated in a beautiful natural habitat in one of Canada's largest urban parks. Opening its doors on August 15, 1974 the Toronto Zoo has been able to adapt throughout the years developing a vision to "educate visitors on current conservation issues and help preserve the incredible biodiversity on the planet", through their work with endangered species, plans for a wildlife health centre and through their Research & Veterinary Programs. I believe it would be appropriate to introduce a honourary street name for the section of Meadowvale Road between Highway 401 and Old Finch Avenue to recognize the only public entrance to the Toronto Zoo. -

Update on Metrolinx Transit Expansion Projects –

June 8th, 2021 Sent via E-mail Derrick Toigo Executive Director, Transit Expansion Division Toronto City Hall 24th fl. E., 100 Queen St. W. Toronto, ON M5H 2N2 Dear Derrick, Thank you for your ongoing support and close collaboration in advancing Metrolinx transit expansion projects across the City of Toronto. The purpose of this letter is to respond to your letter dated May 13, 2021 which transmitted City Council’s decisions of April 7th and 8th, 2021, where Toronto City Council adopted the recommendations in agenda item MM31.12: Ontario Line - Getting Transit Right: Federal Environmental Assessment and Hybrid Option Review – moved by Councillor Paula Fletcher, seconded by Councilor Joe Cressy with amendments, we provide the following information. Request for Federal Environmental Assessment In response to the request made by Save Jimmie Simpson! and the Lakeshore East Community Advisory Committee in March 2021 to conduct an environmental assessment of the above- ground section of Ontario Line (the “Project”) through Riverside and Leslieville, on April 16, 2021, the Honourable Jonathan Wilkinson, Federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change (the “Minister”), announced the Project does not warrant designation under the Impact Assessment Act. The Minister’s response is available at the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada website, Reference Number 81350. In making his decision, the Minister considered the potential for the Project to cause adverse effects within federal jurisdiction, adverse direct or incidental effects, public concern related to these effects, as well as adverse impacts on the Aboriginal and Treaty rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada. The Minister also considered the analysis of the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. -

Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto

The City of Toronto Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto May 2019 The City of Toronto Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. ii 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Housing Prices and Costs – Fundamental Factors ...................................................................... 2 3.0 Market Context ........................................................................................................................... 8 4.0 The Conceptual Inclusionary Zoning Policy .............................................................................. 12 5.0 Approach to Assessing Impacts ................................................................................................ 14 6.0 Analysis ..................................................................................................................................... 21 7.0 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................... 34 Disclaimer: The conclusions contained in this report have been prepared based on both primary and secondary data sources. NBLC makes every effort to ensure the data is correct but cannot guarantee -

December 1982

TORONTO FIELD NATURALIST Number 352, December 1982 Br-id~ing the years ••• Sec page 2 TFN 352 This Month's Cover "The Old Mill Bridge", sketched in the field by Mary Cumming In May 1840 a British army officer visited William Gamble's flourmill at the site of the present Old Mill and wrote this interesting description of the Humber Valley where the Old Mill Bridge now stands : "This mi 11 is on the right bank of the Humber about three mi 1es from the 1ake in a small circular valley bounded partly by abrupt banks and partly by rounded ;1 knolls . At the upper end the highlands approach one another forming a narrow i gorge clothed with heavy masses of the original forest. The basin of the gorge ! is completely filled by the river, which issues from it in a narrow stream flow j ing over a stony channel; but below the mill the water becomes deep and quiet i and deviates into two branches to form a small wooded island. "Close to the water's edge is a large mill surrounded by a number of small cottages over the chimneys of which rose the masts of flour barges; and on the bank above, in the midst of green lawn bounded by the forest is a neat white frame mansion commanding a fine view of this pretty spot. 11 The circular valley referred to is presumably the former Marsh 8, now part of King's Mill Park immediately downstream from Bloor Street, which was then used for pasture and cornfields. -

King Street East Properties (Leader Lane to Church Street) Date: June 14, 2012

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act – King Street East Properties (Leader Lane to Church Street) Date: June 14, 2012 Toronto Preservation Board To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Urban Design, City Planning Division Wards: Toronto Centre-Rosedale – Ward 28 Reference P:\2012\Cluster B\PLN\HPS\TEYCC\September 11 2012\teHPS34 Number: SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council state its intention to designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act the properties identified in Recommendation No. 2. The properties are located on the south side of King Street East between Leader Lane and Church Street and contain a series of commercial and institutional buildings dating from the mid-19th to the early 20th century. The City has received an application for a zoning by-law amendment for the redevelopment of this block. Following research and evaluation, staff have determined that the King Street East properties meet Ontario Regulation 9/06, the provincial criteria prescribed for municipal designation under the Ontario Heritage Act. The designation of the properties would enable City Council to regulate alterations to the sites, enforce heritage property standards and maintenance, and refuse demolition. RECOMMENDATIONS City Planning Division recommend that: 1. City Council include the following properties on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties: a. 71 King Street East (with a convenience address of 73 King Street East) b. 75 King Street East (with a convenience address of 77 King Street East) c. 79 King Street East (with a convenience address of 81 King Street East) Staff report for action – King Street East Properties – Intention to Designate 1 d. -

Learn. Discover Tomorrow’S Technology Today

Make. Play. Learn. Discover Tomorrow’s Technology Today Digital PROGRAMS & EVENTS AT YOUR LIBRARY Innovation Hubs SEPTEMBER – DECEMBER 2018 Spaces to learn and explore the latest tech Pop-Up Learning Labs Mobile technology kits come to you Back to School After school activities for kids and teens. Page 3. Indigenous Celebrations Natasha Kanapé Fontaine, Wab Kinew, Thomas King. Page 21. Our Fragile Planet Talks on biodiversity and conservation and DIY workshops to affect change locally. Page 46. tpl.ca/innovate What’s New in our collections ADULT NON FICTION Minimize Injury, The Chemical Mind Time Creative Quest How to Retire Maximize Story of Olive Oil Michael Chaskalson Questlove Overseas Performance Richard Blatchly Kathleen Peddicord Tommy John TEEN GRAPHIC NON FICTION Rise of the Einstein March: Book Three Marco Polo Tetris Dungeon Master Corinne Maier John Lewis Marco Tabilio Box Brown David Kushner CHILDREN’S NON FICTION Bat Citizens Yoga Frog Weird but True! The Brilliant Deep Rodent Rascals Rob Laidlaw Nora Carpenter Canada Kate Messner Roxie Munro National Geographic Kids Visit torontopubliclibrary.ca for more new books, music and movies. Reserve online and pick them up at any branch. On the Cover: The Idea Garden at Toronto Reference Library. IN THIS ISSUE 2 About Our Programs 3 After School Published by Toronto Public Library 789 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario M4W 2G8 6 Author Talks & Lectures 416-393-7000 • torontopubliclibrary.ca 11 Book Clubs & Writers Groups 14 Career & Job Search Help Toronto Public Library Board 15 Computer & Library Training The Toronto Public Library Board meets monthly at 6 pm, September through 18 Culture, Arts & Entertainment June, at the Toronto Reference Library, 789 Yonge Street, Toronto. -

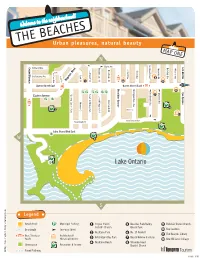

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club .