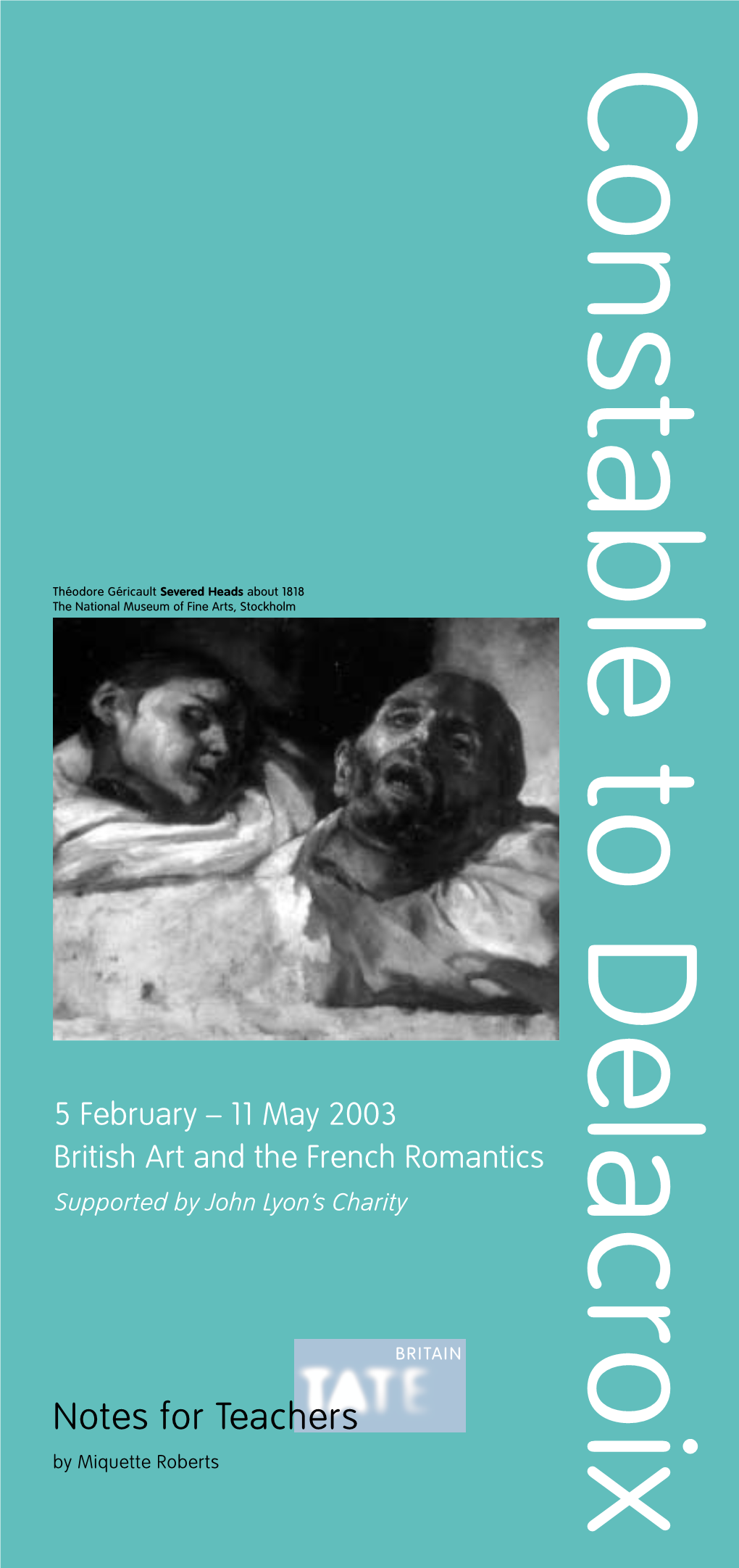

Constable to Delacroix Teachers' Pack: English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articled to John Varley

N E W S William Blake & His Followers Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, p. 184 PAGE 184 BLAKE AN I.D QlJARThRl.) WINTER 1982-83 NEWSLETTER WILLIAM BLAKE & HIS FOLLOWERS In conjunction with the exhibition William Blake and His Followers at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Morton D. Paley (Univ. of California, Berkeley) delivered a lecture, "How Far Did They Follow?" on 16 January BLAKE AT CORNELL 1983. Cornell University will host Blake: Ancient & Modern, a symposium 8-9 April 1983, exploring the ways in which the traditions and techniques of printmaking and painting JOHN LINNELL: A CENTENNIAL EXHIBITION affected Blake's poetry, art, and art theory. The sym- posium will also discuss Blake's late prints and the prints We have received the following news release from the of his followers, and examine the problems of teaching Yale Center for British Art: in college an interdisciplinary artist like William Blake. The first retrospective exhibition in America of the Panelists and speakers include M. H. Abrams, Esther work of John Linnell will open at the Yale Center for Dotson, Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, Peter Kahn, British Art on Wednesday, 26 January. Karl Kroeber, Reeve Parker, Albert Roe, Jon Stallworthy, John Linnell was born in London on 16 June 1792. He and Joseph Viscomi. died ninety years later, after a long and successful career The symposium is being held in conjunction with two ex- which spanned a century of unprecedented change in hibitions: The Prints of Blake and his Followers, Johnson Britain. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

2007 Newsletter

Spring 2007 Collecting China Interdisciplinary symposium expands dialog on Chinese art objects The Newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History 1 Contents Spring 2007 Editor in Chief and Photo Editor: From the Chair From the Chair | 3 Undergraduate Student Linda Pellecchia News | 15 Titles Editor: David M. Stone No doubt, you’ve noticed that the Art History newsletter has changed its Art History Club | 15 Art Director: Don Shenkle look and now has a name, Insight. The department, launched more than Undergraduate Awards | 15 Editorial Coordinator: forty years ago, has fl ourished and Insight allows us to spread the news Connee McKinney of our extraordinary record of accomplishments. Some news builds on Secretarial Assistance: Eileen Larson, traditional strengths. Other items refl ect exciting new directions. Our Deb Morris, Tina Trimble focus on American art will expand next year with the arrival of a new Graduate Student News | 16 “Collecting ‘China’” — Insight is produced by the Department colleague in the history of African American art and another in the 19th An International Gem | 4 Graduate Awards | 16 of Art History as a service to alumni and 20th-century art of the United States. Our curriculum has, on the Graduate Student News | 16 and friends of the Department. We are other hand, expanded globally beyond America and Europe. We now Graduate Degrees Granted | 17 always pleased to receive your opin- teach the arts and architecture of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Art News from Alumni | 18 ions and ideas. Please contact Eileen History undergraduate and graduate students have garnered prestigious Larson, Old College 318, University of grants and awards. -

John Constable (1776-1837)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN John Constable (1776-1837) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

The Romantic Sensibility: the Sublime

The Romantic sensibility: the Sublime The sublime is a feeling associated with the strong emotion we feel in front of intense natural phenomena (storms, hurricanes, waterfalls). It generates fear but also attraction. Origin: the term has Latin origins and refers to any literary or artistic form that expresses noble, elevated feelings. Distinction between the beautiful and the sublime: first made by Addison and then by Burke (A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful). The beautiful refers to the qualities of the object (the work of art) and is related to the classical ideas of harmony and perfection, while the sublime is the sensation felt by the perceiver. Different effects of the sublime: minor effects: admiration, respect; major effects: terror, fear. • What causes the sublime: fear of pain, vastness of the ocean, obscurity, powerful sources, the infinite, the unfinished, magnificence and colour (sad, dark colours). The sublime is caused either by what is great and immeasurable or by natural phenomena which underline the frailty of man. • Influence on late 18th century literature: this feeling is central in the works of Romantic poets and Gothic novelists, and is linked to a passion for extreme sensations. • Influence on painting: painters like Turner and Constable wanted to express the sublime in visual art. They were landscape painters and, although in different ways, they emphasized the strength of natural elements and studied the effects of different weather conditions on the landscape. For some aspects, they influenced the French impressionists. Romanticism in English painting • Nature and rural life were key-elements of English Romanticism and they were well represented in landscape painting. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Explore the Painting John Constable Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831

Explore the painting John Constable Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831 Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831 John Constable (1776 – 1837) Photograph © Tate, London 2013 Purchased with assistance from the Heritage Lottery Fund, The Manton Foundation, the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation) and Tate Members. When this painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy, Constable quoted nine lines from The Four Seasons: Summer (1727) by Scottish poet James Thompson to expand on its meaning. As from the face of heaven the scatter’d clouds Tumultous rove, th’interminable sky Sublimer swells, and o’er the world expands A purer azure. Through the lightened air A higher lustre and a clearer calm Diffusive tremble; while, as if in sign Of danger past, a glittering robe of joy, Set off abundant by the yellow ray, Invests the fields, and nature smiles reviv’d James Thompson, The Seasons: Summer (1727) www.museumwales.ac.uk 1 The poem tells the mythical tale of young lovers Celadon and Amelia. As they walk through the woods in a thunderstorm, the tragic Amelia is struck by lightning, and dies in her lover’s arms. The poem has a religious message: it is an exploration of God’s power, and man’s inability to control his own fate. It is also a poem of hope and redemption. The rainbow appears as a ‘sign of danger past’. The subject has clear resonances with Constable’s own personal grief. His wife Maria died of tuberculosis in 1828, after just twelve years of marriage. It is likely that the poem had special significance for the young couple. -

All at Sea: Romanticism in Géricault's Raft of the Medusa

All at Sea: Romanticism in Géricault's Raft of the Medusa Galven Keng Yue Lee All at sea. We – receptacles, tentacles Of ingestion and Assemblage. A mass of ever-dying, ever-living Vapid waves. All at sea. ~ Galven Keng Yue Lee Plate 1: Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1819, oil on canvas, 491 x 716 cm. Source: Musée du Louvre, Paris. Fair use is claimed for not-for-profit educational & scholarship purposes. Abstract Théodore Géricault’s painting, Raft of the Medusa, has long been regarded as a quintessentially Romantic painting. Yet it was unprecedented when it was exhibited at the 1819 Salon by its raw and direct appeal to the viewer’s 1 The ANU Undergraduate Research Journal emotions, and represented an early stage in French Romantic painting. In this paper, I argue that the painting was an original, logical outcome of the social and political turbulence that plagued French society in the early nineteenth century and which also impinged itself on the personal circumstances of Géricault’s life. It is through this general malaise and sense of crisis that the painting can not only be seen as an authentic product of its time, but also one that reflected the distinctly personal nature of the Romantic painting, through the intense personal involvement and identification of Géricault with its creation and subsequent legacy. Romanticism in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa is a stunning piece that strikes the viewer with its intense, emotional representations of hope and hopelessness. The pointless suffering of the denizens of the raft eradicate any pretensions to heroic achievement or tragic sacrifice; only the surging waves of the ocean respond without sympathy to their cries for salvation from a suffering which has only brought them to the pits of unheroic despair—drawing us within the vacant expression of the older man in the left foreground clutching onto the limp body of a younger male, possibly his son. -

The Raft of the Medusa the Story of a Painting, the Painting of a Story

The Raft of the Medusa The story of a painting, the painting of a story Scheme of Work Suitable for KS4 pupils Written and Designed by David Herbert Drama and Education Consultant [email protected] [Image of The Raft of the Medusa available at <www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/raft-medusa>] [For copyright reasons some visual images included in the original Resource Pack have been omitted here.] Contents Introduction..................................................................................p.3 Aims of the Scheme.....................................................................p.4 Tasks............................................................................................p.4 • The word “trapped” • Outline of story • Stages of Degeneration • Props • Lyrics to the song • News report Evaluation....................................................................................p.8 The Written Portfolio....................................................................p.9 Sources......................................................................................p.10 • The Raft of the Medusa story • Stages of Degeneration Portfolio Worksheets..................................................................p.13 • Drama Coursework – Stages of Degeneration • Storyboarding • Trapped evaluation Skills to allow students to explore in more depth.......................p.17 Reading List...............................................................................p.18 2 Introduction This scheme of work has been written and designed -

Wreck: Gericault and the Body in Pieces

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2019 Being human: The figure in art Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa Mark Ledbury 12 / 13 June 2019 Lecture summary: This lecture examines one of the great works of nineteenth-century Art, Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, 200 years after the painting was first seen. It explores Gericault’s fascination with bodies, but also the political and cultural impact of a painting in its time and beyond. The wreck of the Medusa through incompetence and fear , the subsequent appalling suffering of the occupants of the Raft, caused scandal in the France of the recently restored Monarchy , and Gericault used both his fascination with human and animal bodies and his training in neo-classical studios to very powerful effect in a painting of enormous scale, ambition and effort. Slide list: 1. Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, (Oil on canvas, 1817-19, 4,91 m. x 7,16 m, Paris: Louvre) 2. Horace Vernet, Portrait of Géricault, (Oil on Canvas, 1822 or 3, New York, Metropolitan Museum) 3. J-A-D Ingres, Grande Odalisque (1812-18, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 4. A-L Girodet, Pygmalion (1818-19, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 5. Achille Etna Michallon, The Death of Roland (oil on canvas, 1818, Paris: Louvre) 6. Géricault, Horse Studies,(Graphite on Paper, c.1812-14, Getty Museum, Los Angeles) 7. Géricault, Charging Chasseur, or An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging 1812, Oil on Canvas, Paris, Louvre 8. Géricault, Wounded Cuirassier leaving the Battle (1814, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 9. -

The Colour of Words

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Yurss Lasanta, Paula; Font, Carme, dir. The colour of words : crafting links between romantic poets and painters. 2014. 42 pag. (836 Grau en Estudis d’Anglès i Espanyol) This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/123374 under the terms of the license Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Grau en Estudis Anglesos i d'Espanyol TFG ‐ Treball de Fi de Grau The Colour of Words: Crafting Links between Romantic Poets and Painters PAULA YURSS LASANTA SUPERVISOR: CARME FONT PAZ 6TH OF JUNE 2014 John Constable, Sketch for ‘Hadleigh Castle’, 1829 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Wordsworth and Constable: Essential Passions in Nature .................................................. 4 Chapter 2: Byron and Tuner: Beyond the Romantic Turbulence .......................................................... 11 Chapter 3: William Blake against Himself ........................................................................................... 17 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................... 26 Appendix ............................................................................................................................. 30 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 38