Status Quo Changing Boxers and the Media's Response Through Championing “White Hopes”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Author(s): DEREK H. ALDERMAN, JOSHUA INWOOD and JAMES A. TYNER Source: Southeastern Geographer , Vol. 58, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 227-249 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Southeastern Geographer This content downloaded from 152.33.50.165 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 18:12:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Race, Reputation, and the Politics of Black Villainy: The Fight of the Century DEREK H. ALDERMAN University of Tennessee JOSHUA INWOOD Pennsylvania State University JAMES A. TYNER Kent State University Foundational to Jim Crow era segregation and Fundacional a la segregación Jim Crow y a discrimination in the United States was a “ra- la discriminación en los EE.UU. -

Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, a Public Reaction Study

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study Full Citation: Randy Roberts, “Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study,” Nebraska History 57 (1976): 226-241 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1976 Jack_Johnson.pdf Date: 11/17/2010 Article Summary: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, played an important role in 20th century America, both as a sports figure and as a pawn in race relations. This article seeks to “correct” his popular image by presenting Omaha’s public response to his public and private life as reflected in the press. Cataloging Information: Names: Eldridge Cleaver, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louise, Adolph Hitler, Franklin D Roosevelt, Budd Schulberg, Jack Johnson, Stanley Ketchel, George Little, James Jeffries, Tex Rickard, John Lardner, William -

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis B r i a n D . B u n k 1- Department o f History University o f Massachusetts, Amherst The African-American press created images o f Harry Will: that were intended to restore the image o f the black boxer afterfack fohnson and to use these positive representations as effective tools in the fight against inequality. Newspapers high lighted Wills’s moral character in contrast to Johnsons questionable reputation. Articles, editorials, and cartoons presented Wills as a representative o f all Ameri cans regardless o f race and appealed to notions o f sportsmanship based on equal opportunity in support o f the fighter's efforts to gain a chance at the title. The representations also characterized Wills as a race man whose struggle against boxings color line was connected to the larger challengesfacing all African Ameri cans. The linking o f a sportsfigure to the broader cause o f civil rights would only intensify during the 1930s as figures such as Joe Louis became even more effec tive weapons in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. T h e author is grateful to Jennifer Fronc, John Higginson, and Christopher Rivers for their thoughtful comments on various drafts of this essay. He also wishes to thank Steven A. Riess, Lew Erenberg, and Jerry Gems who contribu:ed to a North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) conference panel where much of this material was first presented. Correspondence to [email protected]. I n W HAT WAS PROBABLY T H E M O ST IMPORTANT mixed race heavyweight bout since Jim Jeffries met Jack Johnson, Luis Firpo and Harry Wills fought on September 11, 1924, at Boyle s Thirty Acres in Jersey City, New Jersey. -

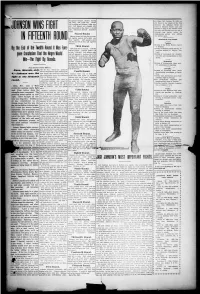

Fight in the Fifteenth

1 son appears stronger clinches forcing at Colma CaL October 16 1909 are Jeff back Jeff sends left Clinch still fresh in the minds of the ring 1 Jeff is smiling and Johnson looks wor- ¬ followers He defeated Burns on ried Jeff slipped into straight left points in fourteen rounds and put but was patted on the cheek a second Ketchel to selep in the twelfth round bell Anybodys later Clinchedat the His fight with Ketchelwas the last of- 1 round Johnsons ring battles before the Second Round championship contest with Jeffrie Johnson slings left into ribs another was agreed upon jab slightly marred Jeffs right eye They sparred Jeff assumes such SPORTS OF THE WEEK Johnson sent left to chin and uppercut with left Tuesday Opening of the Royal Henley regatta Third Round In England End of Twelfth Round It Was Fore- ¬ By the the Jeff sends left to stomach Clinches Opening of Brighton Beach Racing As- ¬ and they break Johnson dashes left sociation meeting at Empire City to nose Clinched Jack missed right track gone Conclusion That the Negro Would and left uppercuts Johnson tries with Opening of tournament for Connecti- ¬ a vicious right to head but Jim ducks cut state golf championship at New and clinches Jack is cautious in break- ¬ Haven WinThe Fight By Ronnds away Johnson sends two little rights to head Clinches Johnson tries with Wednesday an uppercut but Jim sent a light left Opening of international chess mast- ¬ to short ribs Just before the bell Jeff ers tournament at Hamburg light hand to head Even From Mondays Extra Edition sent left at end -

The Johnson-Jeffries Fight and Censorship of Black Supremacy

THE JOHNSON-JEFFRIES FIGHT 100 YEARS THENCE: THE JOHNSON-JEFFRIES FIGHT AND CENSORSHIP OF BLACK SUPREMACY Barak Y. Orbach* In April 2010, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in United States v. Stevens, in which the Court struck down a federal law that banned the depiction of conduct that was illegal in any state. Exactly one hundred years earlier, without any federal law, censorship of conduct illegal under state law and socially con- demned mushroomed in most towns and cities across the country. In the summer of 1910, states and municipalities adopted bans on prizefight films in order to censor black supremacy in controver- sial sport that was illegal in most states. It was one of the worst waves of movie censorship in American history, but it has been largely ignored and forgotten. On the Fourth of July, 1910, the uncompromising black heavy- weight champion, Jack Johnson, knocked out the “great white * Associate Professor of Law, The University of Arizona. www.orbach.org. This Article greatly benefited from the comments and criticism of Jean Braucher, Grace Campbell, Jack Chin, Paul Finkelman, Deb Gray, Sivan Korn, Anne Nelson, Carol Rose, and Frances Sjoberg. Judy Parker, Pam DeLong, and Carol Ward assisted in processing archive documents. The outstanding research support and friendship of Maureen Garmon made the writing of this Article possible. Additional materials are available at www.orbach.org/1910. 270 2010] The Johnson-Jeffries Fight 271 hope,” Jim Jeffries, in what was dubbed by the press and promoters as “the fight of the century.” Jeffries, a former heavyweight cham- pion himself, returned to the ring after a five-year retirement to try to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. -

“Jack” Johnson

June 21, 2016 The U.S. Commission On Civil Rights Statement Requesting The Posthumous Pardon Of John Arthur “Jack” Johnson 70 years ago this month, John Arthur “Jack” Johnson died in a car accident on June 10, 1946.1 Mr. Johnson, the son of former slaves, rose to become boxing’s Heavyweight Champion of the World in 1908 and was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954. An outspoken and controversial figure in his day, Mr. Johnson was initially denied the opportunity to fight for the heavyweight title because the championship was closed to African-Americans. He was a fierce critic of Jim Crow laws and the prevailing enforced customs of racial segregation. After he gained the title, white Americans began a search for a white boxer who could defeat Mr. Johnson, an effort dubbed the search for “the great white hope.” Jim Jefferies, an undefeated former champion, agreed to come out of retirement to fight Mr. Johnson as a result of this search. Mr. Johnson’s victory in that fight sparked riots across the country; white mobs attacked and murdered African-Americans. Racial resentment against Mr. Johnson was heightened by his relationships with white women. On October 18, 1912, he was arrested on a charge that his relationship with a white woman, Lucille Cameron, violated the Mann Act, which prohibited interstate and foreign transportation of women and girls “for immoral 1 Biographical information is taken from Congressional findings in a resolution calling for Mr. Johnson’s pardon, passed as part of the Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub.L. -

Debra Deberry Clerk of Superior Court Dekalb County

Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County (March 31, 1878 – June 10, 1946) First African-American World Heavyweight Boxing Champion John Arthur “Jack” Johnson was born in Galveston, Texas, in 1878, the first son of Henry and Tina Johnson, two former slaves who worked as a janitor and dishwasher to support their nine children. His father, Henry, also served as a civilian teamster of the Union’s 38th Colored Infantry, and was a role model for his son. In spite of his father’s small frame, Jack Johnson grew to be an intimidating 6’2”, earning the nickname, “The Galveston Giant.” After completing only a few years of school, Johnson dropped out and began working on boats and sculleries in Galveston. At the age of 16, he traveled to New York and Boston before returning home to fight in his first unofficial bout. After winning a local fight and taking home a prize of $1.50, Johnson began seeking bigger opponents. His boxing skills were sharpened when he met Walter Lewis who taught Johnson to use his size and strength to strike his opponents. Although he fought in a series of fights, earning his a reputation amongst black fighters, Johnson had his eyes set on a bigger prize, Heavy Weight Champion. The current Heavy Weight Champion title was held by white boxer, Jim Jeffries, but Jeffries, like other white boxers, refused to fight Johnson. But Jack Johnson, being a spirited and talented fighter, caught the attention of Tommy Burns, a white fighter who succeeded Jeffries in his retirement as Heavy Weight Champion. -

Road Notez David Paige (Free) Sept

--------------- Calendar • On the Road --------------- Jay-Z is set to follow up his successful sum- Datsik w/Funtcase, Protohype ($20-$30) Nov. 8 Egyptian Room Indianapolis mer mega-tour with Justin Timberlake with David Bromberg Quintet ($35) Oct. 11 The Ark Ann Arbor some headlining dates of his own in support Road Notez David Paige (free) Sept. 20 CS3 Fort Wayne of his newest opus Magna Carta Holy Grail. Debby Boone ($30) Oct. 20 Niswonger Performing Arts Center Van Wert, OH Unless you’re willing to travel a great dis- CHRIS HUPE Deer Tick Oct. 11 Majestic Theatre Detroit tance, you’ll have to wait until the new year Deer Tick Oct. 12 Otto’s Dekalb, IL to witness the Magna Carter World Tour, as The Delta Saints ($5) Sept. 27 Dupont Bar & Grill Fort Wayne Deltron 3030 w/Itch Oct. 19 House of Blues Chicago it doesn’t venture into this area until January 2014. Cleveland gets first crack at H.O.V.A. Dennis Miller ($40-$47) Oct. 3 Sound Board Detroit January 8, followed by Chicago and Detroit January 9 and 10, respectively. The Devil Wears Prada w/The Ghost Inside, Volumes, Texas in July Nov. 2 Royal Oak Music Theatre Royal Oak, MI On the same day Mr. Carter made his tour announcement, Kanye West announced his The Devil Wears Prada w/The Ghost Inside, Volumes, Texas in July Nov. 3 Bogart’s Cincinnati The Devil Wears Prada w/The Ghost Inside, Volumes, Texas in July Nov. 5 House of Blues Cleveland Yeezus Tour, with stops in 23 cities. -

The Brown Bomber Battles Hitler's Favorite Fighter

GreatMomentsinSports_v14_toprint 04/02/12 The Brown Bomber Battles Hitler’s Favorite Fighter Heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali was famous for loudly proclaiming, “I am the greatest.” Yet even Ali would probably agree that there was one fighter who was at least his equal, if not even greater. That man was known as the Brown Bomber—world heavyweight champion Joe Louis. 1 GreatMomentsinSports_v14_toprint 04/02/12 2 RUTH ROUFF Joe Louis was not exactly a natural at boxing. As a teenager in Detroit in 1932, he was knocked down seven times in his first amateur fight. But his family was very poor, and he dreamed of making enough money to lift them all out of poverty. So he kept training and soon started winning. Noticing his raw power, two fight managers took him to see a veteran trainer, Jack Blackburn. Although Blackburn was himself black, he preferred to work with white fighters. There were two reasons for this. One was that in the 1930s it was much easier for whites to get a shot at title fights. This was partly a white reaction to black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, the title-holder from 1908–1915. At a time when blacks were supposed to “know their place,” Johnson went out of his way to anger whites. He humiliated his opponents. He loved to show off his money by spending it on flashy clothes, fast cars, and the late-night bar scene. Worst of all, he paraded around with white women on his arm. Some might say that Johnson was simply being himself. That was certainly true. -

Jack Johnson: Victim Or Villain

ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, SUNDEE KATHERINE. Jack Johnson: Victim or Villain. (Under the direction of Dr. Linda McMurry, Dr. Pamela Tyler, and Dr. Walter Jackson.) Jack Johnson reigned as the first African-American heavyweight champion of the world from 1908 until 1915. Unfortunately, unlike future African-American athletes such as Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson, Jack Johnson infuriated Americans of all ages, classes, races, and sexes with his arrogant attitude; his expensive and usually imported automobiles, champagne, and cigars; his designer clothes and jewelry; his frequent trips to Europe, usually in the company of at least one beautiful white woman; his inclination to gamble and race sports cars; and his many well-publicized nights of dancing and playing jazz on his prized seven foot bass fiddle. However, his worst offenses, during his reign as heavyweight champion, were his two marriages to and numerous affairs with white women. The purpose of the research has been to place Jack Johnson within the context of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century culture, economics, law, politics, race, and sex. The influences of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century American commercialization, immigration, industrialization, and urbanization on perceptions of femininity, masculinity, sexuality, and violence are investigated; and the implications of Jack Johnson’s defiance of racial and sexual constraints on the African- American community are interpreted. Jack Johnson: Victim or Villain by Sundee Katherine Williams A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts HISTORY Raleigh 2000 APPROVED BY: Dr. -

Botanical Roots LAST CHANCE! Don’T Miss This Final Concert of the Concert Series 2013 Botanical Roots Series!

--------------- Calendar • On the Road --------------- Korn have announced a few dates to pre- Burning the Day, A Fall To Break, Conquest, Two Ton Avil, Low Twelve, Idiom and more Sept. 21 Deluxe at Old National Centre Indianapolis cede the release of their new album, The Indigenous Oct. 18 Slippery Noodle Inn Indianapolis Paradigm Shift. A couple of dates are in the Road Notez Indy Jazz Fest feat. Allen Toussaint, Ramsey Lewis, Funk + Soul, Diane Schuur, region, with the band visiting Detroit Octo- Mark Sheldon, Ravi Coltrane, Jeff Coffin and more Sept. 12-21 Various locations Indianapolis ber 1 and Chicago the following night. The CHRIS HUPE Inter Arma w/Woe Sept. 15 Brass Rail Fort Wayne Paradigm Shift features the return of guitar- J-Roddy Walston & the Business Sept. 6 Deluxe at Old National Centre Indianapolis ist Brian “Head” Welch into the Korn machine, and, if the title of the record indicates Jack Johnson w/Bahamas ($69.50) Sept. 29 E.J. Thomas Hall Akron, OH Jack Johnson Oct. 5 Murat Theatre Indianapolis anything, the band will heading in a new direction with its music. That’s usually not a Jack Johnson Oct. 6 Chicago Theatre Chicago good thing, but you never know. The Paradigm Shift hits store shelves October 8. Asking Jamey Johnson Oct. 10 Canopy Club Urbana, IL Alexandria and Love and Death open the shows. Jason Aldean w/Jake Owen, Thomas Rhett Sept. 1 Klipsch Music Center Noblesville Keith Urban has announced the final leg of his Light the Fuse tour, with most dates tak- Jeff Dunham Nov. -

Trump Pardons Late Boxer Jack Johnson by JILL COLVIN Cades Ago with Biogra- Fight” If He Really Started Tered the Same Ring

Page 6, The Daily Review, Morgan City, La., Friday, May 25, 2018 Trump pardons late boxer Jack Johnson By JILL COLVIN cades ago with biogra- fight” if he really started tered the same ring. He nation’s history and during the Civil War. Associated Press phies, dramas and docu- working out. then beat a series of marks a milestone that President George W. WASHINGTON — mentaries, was convicted Lewis said Johnson had “great white hopes,” cul- the American people can Bush pardoned Charles President Donald Trump in 1913 by an all-white been an inspiration to him minating in 1910 with and should be proud of.” Winters, an American vol- on Thursday granted a jury for violating the personally, while Stallone the undefeated former Johnson’s imprison- unteer in the Arab-Israeli rare posthumous pardon Mann Act for traveling said Johnson had served champion, James J. ment forced him into the War convicted of violating to boxing’s first black with his white girlfriend. as the basis of the charac- Jeffries. shadows of bigotry and the U.S. Neutrality Acts heavyweight champion, That law made it illegal ter Apollo Creed in his McCain previously told prejudice, and continues in 1949. clearing Jack Johnson’s to transport women “Rocky” films. The Associated Press to stand as a stain on our Haywood had wanted name more than 100 across state lines for “im- “This has been a long that Johnson “was a box- national honor,” McCain Barack Obama, the na- years after what many moral” purposes.” time coming,” he said. ing legend and pioneer has said.