Searching for the Curriculum of Sriwijaya1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Record of Collected Proofs of the Efficacy of the Diamond Sutra: Jin’Gang Bore Jing Jiyan Ji 金剛般若 經集驗記 Composed by Meng Xianzhong 孟獻忠, Adjutant of Zizhou 梓州司馬

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): Jin’gang bore jing jiyan ji _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Collected Proofs of the Efficacy of the Diamond Sutra _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Collected Proofs of the Efficacy of the Diamond Sutra 297 A Record of Collected Proofs of the Efficacy of the Diamond Sutra: Jin’gang bore jing jiyan ji 金剛般若 經集驗記 Composed by Meng Xianzhong 孟獻忠, Adjutant of Zizhou 梓州司馬 Roll One (with Preface) Prajñāis the mother of the wisdom of all Buddhas and the quintessence of the consummate path. Being the wellspring of the Dharma ocean, it is in fact the actual secret storehouse of the Tathāgata. When words are spoken, the path is severed; when the mind functions, the abode is destroyed.1 Being beyond name and appearance, as well as the elements and fields of cognitive experience, it is said to cognize and yet not grasp. It is free from seeing, hearing, feeling, and knowing. When discriminative consciousness expresses it, it becomes more distant. Without practice, there is no benefit; one thus perfects its merit. Without abiding, there is no defilement; one thus attains its wisdom. For those who in- vestigate its wonders, [wherever] they practice are places of the [Buddhist] path; for those who comprehend its principles, their undertakings are Bud- dhist practice. It extends to the twelve classics2 and the eighty-four thousand teachings,3 and equals the competing brilliance of the sun, moon, and 1 These verses come from roll 54 of the Dazhidu lun 大智度論 (Sk. -

The Emergence of Essence-Function (Ti-Yong) 體用 Hermeneutics in the Sinification of Indic Buddhism: an Overview

The Emergence of Essence-Function (ti-yong) 體用 Hermeneutics in the Sinification of Indic Buddhism: An Overview A. Charles Muller (University of Tokyo) 국문요약 본질-작용(體用, Ch. ti-yong, J. tai-yū; 일본에서 불교학 이외의 연구에서 는 tai-yō) 패러다임은 기원전 5세기부터 근대 시기에 이르기까지 중국, 한국, 일본의 종교・철학적 문헌을 해석할 때에 가장 널리 사용된 해석학적 틀로 볼 수 있다. 먼저 중국에서는 유교, 도교, 불교에 적용되는 과정에서 풍부한 발전 을 이루었는데, 특히 인도 불교의 중국화 과정에서 폭넓게 적용되었다. 그리고 종종 理事(li-shi)와 유사한 형태로 화엄, 천태, 선과 같은 중국 토착 불교 학파 불교학리뷰 (Critical Review for Buddhist Studies) 19권 (2016. 6) 111p~152p 112 불교학리뷰 vol.19 들의 철학을 위한 토대를 형성하였다. 나아가 송대 신유학(新儒學)에서 ‘체용’ 의 용례는 특히 잇따라 나타나는 또 다른 유사형태인 理氣(li-qi)의 형식으로 변화하고 확장되었다. 불교와 신유학 모두 한국에 뿌리를 내리면서 한국 학자 들은 신유교와 불교 각각의 종교에 대한 해석뿐 아니라, 둘 사이에 있었던 대 화와 논쟁에도 체용 패러다임을 폭넓게 적용하였다. 본 논문은 동양과 서양 모 두의 불교학에서 거의 완전히 무시되었던 이 지극히 중요한 철학적 패러다임 에 관한 논의를 되살려 보고자 한다. 그리고 이것을 중국 불교 주석문헌들 초 기의 용례, ≷대승기신론≸속에 나타난 그 역할, 더불어 한국 불교, 특히 원효와 지눌의 저작에서 사용된 몇 가지 용례들을 조사함으로써 시도할 것이다. 주제어: 본질-작용(體用), 이사(理事), 이기(理氣), ≷대승기신론≸, 중국불교, 원효, 지눌 The Emergence of Essence-Function (ti-yong) 體用 Hermeneutics in the Sinification of Indic Buddhism … 113 I. Essence-function 體用: Introduction This examination of the place of the essence-function paradigm 體用 (Ch. ti-yong, K. che-yong, J. -

Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and Its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism Xican Li1 1 School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China Correspondence: Xican Li, School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, 510006, Guangzhou, China. Tel: 86-203-935-8076. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 21, 2015 Accepted: August 31, 2015 Online Published: September 2, 2015 doi:10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 Abstract Guangxiao Temple is located in Guangzhou (a coastal city in Southern China), and has a long history. The present study conducted an onsite investigation of Guangxiao’s precious Buddhist relics, and combined this with a textual analysis of Annals of Guangxiao Temple, to discuss its history and multi-roles in Asia-Pacific Buddhism. It is argued that Guangxiao’s 1,700-year history can be seen as a microcosm of Chinese Buddhist history. As the special geographical position, Guangxiao Temple often acted as a stopover point for Asian missionary monks in the past. It also played a central role in propagating various elements of Buddhism, including precepts school, Chan (Zen), esoteric (Shingon) Buddhism, and Pure Land. Particulary, Huineng, the sixth Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, made his first public Chan lecture and was tonsured in Guangxiao Temple; Esoteric Buddhist master Amoghavajra’s first teaching of esoteric Buddhism is thought to have been in Guangxiao Temple. -

How Chinese Buddhist Travelogues Changed Western Perception of Buddhism

The Historical Turn: How Chinese Buddhist Travelogues Changed Western Perception of Buddhism MAX DEEG Cardiff University [email protected] Keywords: Faxian, Xuanzang, Yijing, William Jones, Buddhist travelogues DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15239/hijbs.01.01.02 Abstract: Information about Buddhism was scarce and vague at best in the West until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The first Orientalists studying Indian sources had to rely on Hindu texts written in Sanskrit (e.g. Purāṇas) which portrayed the Buddha as an avatāra of the Hindu god Viṣṇu. The situation changed with the discovery of the Pāli texts from Śrī Laṅkā through scholars like George Turnour and the decipherment of the Aśokan inscriptions through James Prinsep by which the historical dimension of the religion became evident. The final confirmation of the historicity of the Buddha and the religion founded by him was taken, however, from the records of Chinese Buddhist travellers (Faxian, Xuanzang, Yijing) who had vis- ited the major sacred places of Buddhism in India and collected other information about the history of the religion. This paper will discuss the first Western translations of these travelogues and their reception in the scholarly discourse of the period and will suggest that the historical turn to which it led had a strong impact on the study and reception of Buddhism—in a way the start of Buddhist Studies as a discipline. Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 1.1 (2018): 43–75 43 44 MAX DEEG n the year of 1786, in his third ‘Anniversary Discourse’ -

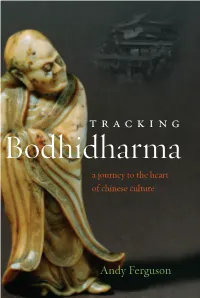

Tracking B Odhidharma

/.0. !.1.22 placing Zen Buddhism within the country’s political landscape, Ferguson presents the Praise for Zen’s Chinese Heritage religion as a counterpoint to other Buddhist sects, a catalyst for some of the most revolu- “ A monumental achievement. This will be central to the reference library B)"34"35%65 , known as the “First Ances- tionary moments in China’s history, and as of Zen students for our generation, and probably for some time after.” tor” of Zen (Chan) brought Zen Buddhism the ancient spiritual core of a country that is —R)9$%: A4:;$! Bodhidharma Tracking from South Asia to China around the year every day becoming more an emblem of the 722 CE, changing the country forever. His modern era. “An indispensable reference. Ferguson has given us an impeccable legendary life lies at the source of China and and very readable translation.”—J)3! D54") L))%4 East Asian’s cultural stream, underpinning the region’s history, legend, and folklore. “Clear and deep, Zen’s Chinese Heritage enriches our understanding Ferguson argues that Bodhidharma’s Zen of Buddhism and Zen.”—J)5! H5<4=5> was more than an important component of China’s cultural “essence,” and that his famous religious movement had immense Excerpt from political importance as well. In Tracking Tracking Bodhidharma Bodhidharma, the author uncovers Bodhi- t r a c k i n g dharma’s ancient trail, recreating it from The local Difang Zhi (historical physical and textual evidence. This nearly records) state that Bodhidharma forgotten path leads Ferguson through established True Victory Temple China’s ancient heart, exposing spiritual here in Tianchang. -

A Comparison of the Themes of the Journey to the West and the Pilgrim’S Progress

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 7, pp. 1243-1249, July 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.7.1243-1249 A Comparison of the Themes of The Journey to the West and The Pilgrim’s Progress Yan Liu English Department, Zhenjiang Watercraft College, No.130 Taohuawu Road, Zhenjiang 212003, China Wenjun Li English Department, Zhenjiang Watercraft College, No.130 Taohuawu Road, Zhenjiang 212003, China Abstract—The Journey to the West, which tells the journey of four Buddhist monks who have overcome many hardships for the purpose of arriving in the West and asking for the Buddhist Scriptures, is one of the “four classics” of China. The Pilgrim’s Progress tells the difficult journey of Christian from the "City of Destruction", his hometown to the "Celestial City". Despite of the sameness of the two stories, that is, the strong religious atmosphere, there are still obvious differences between them. This article tries to compare the themes of the Journey to the West and the Pilgrim’s Progress. At the beginning, we will discuss the themes of the two novels. Then we will compare the differences of the themes and will discover that both of them have revealed the religious belief of “learn virtue and unlearn vice” and criticized the current society. But the aims of the journeys and the attitudes to the new rising class of the authors are of remarkable differences. The purpose of this article is to help the readers appreciate the two stories better, and to have better understanding of the reasons of such differences. -

The Diamond Sutra

THE DIAMOND SUTRA THE DIAMOND SUTRA 1 Diamond Sutra The full Sanskrit title of this text is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (The Vajra Prajna Paramita Sutra). The Buddha said this Sutra may be known as “The Diamond that Cuts through Illusion.” Like many Buddhist sūtras, The Diamond Sūtra begins with the famous phrase, "Thus have I heard." The Buddha finished his daily walk with the monks to gather offerings of food and sits down to rest. The monk Subhūti comes forth and asks the Buddha a question. What follows is a dialogue regarding the nature of perception. The Buddha often uses paradoxical phrases such as, "What is called the highest teaching is not the highest teaching". The Buddha is generally thought to be helping Subhūti unlearn his preconceived, limited notions of the nature of reality and enlightenment. The Diamond Sūtra is a short and well-known Mahāyāna sūtra from the Prajñāpāramitā, or "Perfection of Wisdom" genre, and it emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment. A list of vivid metaphors for impermanence appears in a popular four-line verse at the end of the sūtra: All conditioned phenomena Are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, or shadows; Like drops of dew, or flashes of lightning; Thusly should they be contemplated. A copy of the Chinese version of The Diamond Sūtra, found among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century and dating back to May 11, THE DIAMOND SUTRA 868 C.E. is considered the earliest complete survival of a woodblock printing folio. This discovered text was made over 500 years before the Gutenberg 2 printing press in 1450 C.E. -

The Neglected Pilgrim: How Faxian's Record Was Used (And Was Not Used) in Buddhist Studies

The Neglected Pilgrim: How Faxian’s Record Was Used (and Was Not Used) in Buddhist Studies MAX DEEG Cardiff University [email protected] Keywords: Faxian, Foguo ji, Buddhist Studies, Research History DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15239/hijbs.02.01.02 Abstract: This paper focuses on the role of Faxian’s Foguo ji, Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms (a.k.a Gaoseng Faxian zhuan) in the forma- tion of Buddhist Studies as a discipline in the nineteenth and twenti- eth centuries. It will contextualize the text in the emulating historicist approach of the time which, I would claim and hope to show, led to a certain marginalization of the Record due to the typical ideological parameters inherent in the positivist and historicist interpretation of sources, such as the idea of authenticity and reliability through authorship and through the information given in the source. In this context, Faxian’s Record had the disadvantage of being relatively short, restricted in terms of geographical range, and being linked to an author about whom not much was known. As a consequence, Faxian’s Record was and is mostly used in a complementary way to either corroborate pieces of information from other sources—mainly from Xuanzang’s Da Tang Xiyu ji which had become the main authority—hence establishing it as the earliest text of its ‘genre’ a his- torical terminus ad quem, or it has to fill gaps of information in those other sources (e.g. the report on Siṃhala/Śrī Laṅkā). 16 Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 2.1 (2019): 16–44 HOW FAXIAN’S RECORD WAS USED (AND WAS NOT USED) 17 espite the attention Faxian (337–422) and his record, the 法顯 Foguo ji (or Gaoseng Faxian zhuan ) has D 佛國記 高僧法顯傳 experienced in a little bit more than two decades by the publication of five translations into Western languages (English, German, Italian, French, Spanish), the author and his text are, without any doubt, not as well-known as the two Chinese Buddhist travellers of the Tang period, Xuanzang (602–664) and Yijing (635–713), and 玄奘 義淨 their works. -

A Pure Mind in a Clean Body

A PURE MIND Bodily Care in the Buddhist Monasteries of Ancient India and China Bodily Care in the Buddhist Monasteries of Ancient India and Buddhist monasteries, in both Ancient India and China, have played a crucial social role, for religious as well as for lay people. They rightfully attract the attention of many scholars, discussing historical backgrounds, institutional networks, or influential masters. Still, some aspects of monastic IN life have not yet received the attention they deserve. This book therefore A aims to study some of the most essential, but often overlooked, issues of CL Buddhist life: namely, practices and objects of bodily care. For monastic EAN authors, bodily care primarily involves bathing, washing, cleaning, shaving and trimming the nails, activities of everyday life that are performed by lay BO people and monastics alike. In this sense, they are all highly recognizable A PURE MIND D and, while structuring monastic life, equally provide a potential bridge Y between two worlds that are constantly interacting with each other: IN A CLEAN BODY monastic people and their lay followers. Bodily practices might be viewed as relatively simple and elementary, Bodily Care but it is exactly through their triviality that they give us a clear insight in the Buddhist Monasteries into the structure and development of Buddhist monasteries. Over time, of Ancient India and China Buddhist monks and nuns have, through their painstaking effort into regulating bodily care, defined the identity of the Buddhist samgha, overtly displaying it to the laity. Ann Heirman & Mathieu Torck Ann Heirman, Ph.D. (1998) in Oriental Languages and Cultures, is Professor of Chinese Language and Culture at Ghent University, Belgium. -

History and Religion Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche Und Vorarbeiten

History and Religion Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten Herausgegeben von Jörg Rüpke und Christoph Uehlinger Band 68 History and Religion Narrating a Religious Past Edited by Bernd-Christian Otto, Susanne Rau and Jörg Rüpke with the support of Andrés Quero-Sánchez ISBN 978-3-11-044454-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044595-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-043725-6 ISSN 0939-2580 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ∞ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents Historyand Religion 1 Section I Origins and developments Introduction 21 Johannes Bronkhorst The historiography of Brahmanism 27 Jörg Rüpke Construing ‘religion’ by doinghistoriography: The historicisation of religion in the Roman Republic 45 Anders Klostergaard Petersen The use of historiography in Paul: Acase-study of the instrumentalisation of the past in the context of Late Second Temple Judaism 63 Ingvild Sælid Gilhus Flirty fishing and poisonous serpents: Epiphanius of Salamis inside his Medical chestagainstheresies 93 Sylvie Hureau Reading sutras in biographies of Chinese Buddhist monks 109 Chase F. Robinson Historyand -

A History of Buddhist Ritual

CHAPTER NINETEEN A HISTORY OF BUDDHIST RITUAL Todd Lewis AQ: woof of Buddhism is not a separate compartment of belief and practice, but a system of symbols, daily life? psychological attitudes, and ritual behavior forming the warp against which the woof of daily life is woven. Manning Nash (1965: 104) Practices of the monks are so various and have increased so much that all of them cannot be recorded. Faxian, Chinese pilgrim in India, 400 CE (Beal 1970: 1, xxx) INTRODUCTION any early scholars held that “true Buddhists” follow a rational, atheistic belief system, Mand that they focus almost exclusively on meditation, solely intent on nirvana realization; and that “popular” practices – especially rituals – represent a deformation of the Dharma (Buddha’s teaching), an unfortunate concession to the masses. It is now clear that this is an absurd projection in the Western historical imagination, an assessment uninformed by textual evidence and anthropological studies. Since householder traditions and non-virtuosi practices have not been central concerns in most research since the inception of modern Buddhist studies (Schopen 1991a), many texts concerned with nonelite belief and practices written in canonical languages, and especially ritual manuals, still remain largely unexplored. So, too, have anthropologists working in vernacular languages neglected the indigenous guidebooks that are in the hands of modern Buddhist monks and priests, the true “working texts” of living Buddhism. As a result, a proper documentary history of Buddhist ritual traditions, either in antiquity or today, simply cannot satisfactorily be written as of yet. To compose an overview of Buddhist ritual, one must rely on what little ritual literature has been translated, accounts by a few Chinese pilgrims who visited India from the fifth to seventh centuries, and then on the accounts about modern Buddhists in missionary and anthropological publications. -

Many Biographies – Multiple Individualities: the Identities of the Chinese Buddhist Monk Xuanzang

Max Deeg Many biographies – multiple individualities: the identities of the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang 1 Introduction What is usually called the school of Buddhist Illusionism or Idealism (or, as others prefer to call it, Phenomenology),1 Yogācāra (Chin. Yujia-xing 瑜伽行) or Vijñānavāda (Weishi-zong 唯識宗), argues that all phenomena experienced as real are just projections of the mind (Skt. citta, Chin. xin 心) or consciousness (Skt. vijñāna, Chin. shi 識) and have no ultimate and intrinsic reality (Skt. asvab- hāva, Chin. wu(zi)xing 無(自)性).2 In this chapter, I will extend and apply this very simplified description of Yogācāra to the question of (religious) individuality and individualisation. The argument I will offer is that processes of individualisation, those ascribed to individuals and groups as well as those described by others in biographical (or auto-biographical) narratives, are always (and only) imagined (Skt. prajñaptimātra, Chin. weijiashe 唯仮設) and are not, thus, historically and/ or ontologically real or ‘true’. I assume that the individual under discussion, the Chinese monk and East Asian Yogācāra master par excellence Xuanzang 玄奘 (600/602–664), would fully agree with such a statement. In this paper I focus on two things: first, on the ways in which individualis- ation is projected – or, according to my chosen terminology, ‘functionalised’ – in the historical sources in the form of narratives about one specific individual; and second, on how this form of individualisation is dependent on specific social and cultural contexts,