The Grotesque in the Poetry of William Wordsworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIT 2 George Crabbe's the Village Book I

George Crabbe: The Village: UNIT 2 GEORGE CRABBE’S THE VILLAGE Book I BOOK I Structure 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction and Background 2.2 Explanation 2.3 Critical Responses 2.4 Suggested Readings 2.5 Check Your Progress : Possible Questions 2.0 OBJECTIVES This unit will help you understand: • The primary themes in Crabbe’s The Village • The eighteenth century tradition of topographical poetry • Scholarly perspectives and responses on The Village 2.1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND George Crabbe’s (1754 – 1832) ‘‘The Village’’, published in 1783, is a narrative poem, following on the footsteps of eighteenth century Augustan topographical poetry. The eighteenth century was replete with poetry which celebrated the rural English countryside as the epitome of pristine beauty. They amalgamated elements of the pastoral and georgics to picture the rural landscape and living as humanity’s ideal goal. Georgics chiefly described specifically named actual localities, but in the eighteenth century, along with describing the natural scenery they usually also gave information about specific rural subject matters giving genre sketches and brief histories of the resident people and their livelihood. The georgics get their name from Virgil’s classical Latin composition ‘‘Georgics’’ which presented agricultural themes and celebrates peaceful rural nature. With John Dryden’s translation of Virgil’s Georgics in 1697, meant for a quintessentially urban literate readership, the rural themes garnered a renewed attention in poetry all throughout the eighteenth century. Some famous instances of Augustan poetry which thematically work around and adapt the georgics are Alexander Pope’s ‘‘Windsor Forest’’ and Thomson’s ‘‘The Seasons’’. -

The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field

CHAPTER 11 The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field We touched on the grottesche as a mode of aggregating decorative fragments into structures which could display the artist’s mastery of design and imagi- native invention.1 The grottesche show the far-reaching transformation which had occurred in the conception and handling of ornament, with the exaltation of antiquity and the growth of ideas of artistic style, fed by a confluence of rhe- torical and Aristotelian thought.2 They exhibit a decorative style which spreads through painted façades, church and palace decoration, frames, furnishings, intermediary spaces and areas of ‘licence’ such as gardens.3 Such proliferation shows the flexibility of candelabra, peopled acanthus or arabesque ornament, which can be readily adapted to various shapes and registers; the grottesche also illustrate the kind of ornament which flourished under printing. With their lack of narrative, end or occasion, they can be used throughout a context, and so achieve a unifying decorative mode. In this ease of application lies a reason for their prolific success as the characteristic form of Renaissance ornament, and their centrality to later historicist readings of ornament as period style. This appears in their success in Neo-Renaissance style and nineteenth century 1 The extant drawings of antique ornament by Giuliano da Sangallo, Amico Aspertini, Jacopo Ripanda, Bambaia and the artists of the Codex Escurialensis are contemporary with—or reflect—the exploration of the Domus Aurea. On the influence of the Domus Aurea in the formation of the grottesche, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, Leiden: Brill, 1969); idem, “Ghirlandaio et l’antique”, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 39 (1962), 419– 55; idem, Le Logge di Raffaello: Maestro e bottega di fronte all’antica (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1977, 2nd ed. -

Susan Glickman. the Picturesque and the Sublime: a Poetics of the Canadian Landscape

Book Reviews Susan Glickman. The Picturesque and the Sublime: A Poetics of the Canadian Landscape. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1998. Pp. xi, 212. $50.00. “I came to the study of Canadian poetry late,” volunteers Susan Glickman in her preface to The Picturesque and the Sublime. “ A poet myself,” she ex- plains, “I wanted to know more about my antecedents, and perhaps because I never studied ‘Canlit’ formally, my reading remained a private pleasure— without obligation, and without preconceptions. It was random and idiosyn- cratic . .” (vii). Suggesting later that she is “not interested in constructing a master narrative,” Glickman describes her book as a collection of essays in literary history, not the unfolding of a thesis. Continuity is implied by the chronological order of the pieces, co- herence by the repetition of themes and variations, but the struc- ture of the book, and of the essays themselves, is ruminative rather than linear. Like the poets who roam through this work, I too wish to wander, ponder, and digress, according to the dictates of the landscape. (x) A promising but misleading catalogue from an author who asserts, at the same time, that her “mandate is twofold: to illuminate the contributions of European theories of the picturesque and the sublime to Canadian depictions of nature, and to explore the critical reception to poems informed by these aesthetics” (x). More narrowly, it is “the argument of this book that eigh- teenth-century aesthetic conventions still inform English Canadian poetry, particularly the poetry of landscape” (ix), which, she contends, articulates an understanding of the sublime that is “unique to this country; indeed, because of its profound contribution to the ideology of our fi rst writers, it is one of the formative ideas of Canadian culture” (59). -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

The Grotesque in El Greco

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME © Författare: Lena Beckman Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Höstterminen 2019 Handledare: Johan Eriksson ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala Universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Lena Beckman Titel och Undertitel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Engelsk titel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Handledare Johan Eriksson Ventileringstermin: Hösttermin (år) Vårtermin (år) Sommartermin (år) 2019 2019 Content: This study attempts to investigate the grotesque in four paintings of the artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos or El Greco as he is most commonly called. The concept of the grotesque originated from the finding of Domus Aurea in the 1480s. These grottoes had once been part of Nero’s palace, and the images and paintings that were found on its walls were to result in a break with the formal and naturalistic ideals of the Quattrocento and the mid-renaissance. By the end of the Cinquecento, artists were working in the mannerist style that had developed from these new ideas of innovativeness, where excess and artificiality were praised, and artists like El Greco worked from the standpoint of creating art that were more perfect than perfect. The grotesque became an end to reach this goal. While Mannerism is a style, the grotesque is rather an effect of the ‘fantastic’.By searching for common denominators from earlier and contemporary studies of the grotesque, and by investigating the grotesque origin and its development through history, I have summarized the grotesque concept into three categories: between form, beyond language and beside the sublime. -

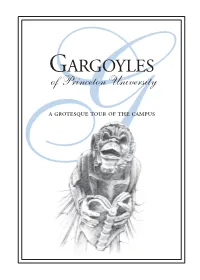

Gargoyles of Princeton University Ga Grotesque Tour of the Campus

GARGOYLES of Princeton University Ga grotesque tour of the campus 1 2 Here we were taught by men and Gothic towers democracy and faith and righteousness and love of unseen things that do not die. H. E. Mierow ’14 or centuries scholars have asked why gargoyles inhabit their most solemn churches and institutions. Fantastic explanations have come downF from the Middle Ages. Some art historians believe that gargoyles were meant to depict evil spirits over which the Christian church had triumphed. One theory suggests that these devils were frozen in stone as they fled the church. Supposedly, Christ set these spirits to work as useful examples to men instead of sending them straight to damnation. Others say they kept evil spirits away. Psychologists suggest that gargoyles represent the fears and superstitions of medieval men. As life became more secure, the gargoyles became more comical and whimsical. This little book introduces you to some men, women, and beasts you may have passed a hundred times on the campus but never noticed. It invites you to visit some old favorites. A pair of binoculars will bring you face-to-face with second- and third- story personalities. Why does Princeton have gargoyles and grotesques? Here is one excuse: … If the most fanciful and wildest sculptures were placed on the Gothic cathedrals, should they be out of place on the walls of a secular educational establishment? (“Princeton’s Gargoyles,” New York Sun, May 13, 1927) Note: Taking some technical license, the creatures and carvings described in this publication are referred to as “gargoyles” and “grotesques.” Typically, gargoyles are defined as such only when they also serve to convey water away from a building. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe “Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by Edgar Allan Poe • Tamerlane and Other Poems (poetry) 1827 • Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (poetry) 1829 • Poems (poetry) 1831 • The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, North America: Comprising the Details of a Mutiny, Famine, and Shipwreck, During a Voyage to the South Seas; Resulting in Various Extraordinary Adventures and Discoveries in the Eighty-fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude (novel) 1838 • Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (short stories) 1840 • The Raven, and Other Poems (poetry) 1845 • Tales by Edgar A. Poe (short stories) 1845 • Eureka: A Prose Poem (poetry) 1848 • The Literati: Some Honest Opinions about Authorial Merits and Demerits, with Occasional Words of Personality (criticism) 1850 Major Themes The most prominent features of Edgar Allan Poe's poetry are a pervasive tone of melancholy, a longing for lost love and beauty, and a preoccupation with death, particularly the deaths of beautiful women. Most of Poe's works, both poetry and prose, feature a first-person narrator, often ascribed by critics as Poe himself. Numerous scholars, both contemporary and modern, have suggested that the experiences of Poe's life provide the basis for much of his poetry, particularly the early death of his mother, a trauma that was repeated in the later deaths of two mother- surrogates to whom the poet was devoted. Poe's status as an outsider and an outcast--he was orphaned at an early age; taken in but never adopted by the Allans; raised as a gentleman but penniless after his estrangement from his foster father; removed from the university and expelled from West Point--is believed to account for the extreme loneliness, even despair, that runs through most of his poetry. -

Modern American Grotesque

Modern American Grotesque Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 1 7/31/2009 11:14:21 AM Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 2 7/31/2009 11:14:26 AM Modern American Grotesque LITERATURE AND PHOTOGRAPHY James Goodwin THEOHI O S T A T EUNIVER S I T YPRE ss / C O L U MB us Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 3 7/31/2009 11:14:27 AM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goodwin, James, 1945– Modern American grotesque : Literature and photography / James Goodwin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-1108-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10 : 0-8142-1108-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-9205-1 (cd-rom) 1. American fiction—20th century—Histroy and criticism. 2. Grotesque in lit- erature. 3. Grotesque in art. 4. Photography—United States—20th century. I. Title. PS374.G78G66 2009 813.009'1—dc22 2009004573 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1108-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9205-1) Cover design by Dan O’Dair Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe Typeset in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 4 7/31/2009 11:14:28 AM For my children Christopher and Kathleen, who already possess a fine sense of irony and for whom I wish in time stoic wisdom as well Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 5 7/31/2009 -

Satirical Imagery of the Grotesque Body of Louis XIV Pushing The

Satirical Imagery ofthe Grotesque Body ofLouis XIV Pushing the Corporeal Limits ofFrance Brittany Nicole Heinrich Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal F ebruary 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts at Mc Gill University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Masters of Arts. © Brittany Nicole Heinrich (2006) Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24868-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24868-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Joseph Cottle and West-Country Romanticism Richard Cronin ______

From The Coleridge Bulletin The Journal of the Friends of Coleridge New Series 28 (NS) Winter 2006 © 2006 Contributor all rights reserved http://www.friendsofcoleridge.com/Coleridge-Bulletin.htm Joseph Cottle and West-Country Romanticism Richard Cronin ____________________________________________________________________________________________ N OCTOBER, 1799, Coleridge travelled from Bristol with his publisher, I Joseph Cottle, to meet Wordsworth at Sockburn-on-Tees. The three men embarked on a tour of Wordsworth’s beloved Lake Country, but on October 30, at Greta Bridge, Cottle left the party and travelled south. ‘It was a tactful departure’, notes Mary Moorman, ‘Wordsworth and Coleridge wanted to be by themselves’.1 That leave-taking has a symbolic value: it marks the birth of the Lake School of Romantic poetry, and yet Joseph Cottle, the man so brusquely dismissed by Moorman, staked a claim to have originated that school himself, and not in the Lake District but some 250 miles to the South, in Bristol: Many might think it no small honour (without the slightest tincture of vanity) to have been the friend, in early life, of such men as Southey, Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Lamb: to have encouraged them in their first productions, and to have published, as it respects each of them, his first Volume of Poems. Typically, this is not quite accurate,2 but it was, as Cottle rightly insisted, ‘a distinction that might never occur again to a Provincial bookseller.’3 It seemed to Cottle an ‘extraordinary circumstance that Mr. Coleridge in his “Biographia Literaria” should have passed over in silence, all distinct reference to Bristol, the cradle of his literature, and for many years his favourite abode.’4 He was moved to publish his Early Recollections to correct Coleridge’s omission, to celebrate a period in the life of his city when ‘so many men of genius were there congregated, as to justify the designation, ‘The Augustan Age of Bristol,”5 and, with pardonable egotism, to remind the reading public of his own status as the provincial west-country Maecenas. -

Architectural Terminology

Architectural Terminology Compiled by By Trail End State Historic Site Superintendent Cynde Georgen; for The Western Alliance of Historic Structures & Properties, 1998 So what is a quoin anyway … other than a great word to have in your head when playing Scrabble®? Or how about a rincleau? A belvedere? A radiating voussoir? If these questions leave you scratching your head in wonder and confusion, you’re not alone! Few people outside the confines of an architect’s office have a working knowledge of architectural terminology. For you, however, that’s about to change! After studying the following glossary, you’ll be able to amaze your friends as you walk through the streets of your town pointing out lancets, porticos, corbels and campaniles. NOTE: The definitions of some terms use words which themselves require definition. Such words are italicized in the definition. Photograph, balustrade, undated (By the Author) Acanthus Leaf - Motif in classical architecture found on Corinthian columns Aedicule - A pedimented entablature with columns used to frame a window or niche Arcade - Series of round arches supported by columns or posts Architrave - The lowest part of a classical entablature running from column to column Ashlar - Squared building stone laid in parallel courses Astragal - Molding with a semicircular profile Astylar - Facade without columns or pilasters Balconet - False balcony outside a window Baluster - The post supporting a handrail Balustrade - Railing at a stairway, porch or roof Architectural Terminology - 1 - www.trailend.org -

Coleridge's Imperfect Circles

Coleridge’s Imperfect Circles Patrick Biggs A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2012 2 Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Note on Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 The Eolian Harp 16 This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison 37 Frost at Midnight 60 Conclusion 83 Bibliography 91 3 Abstract This thesis takes as its starting point Coleridge’s assertion that “[t]he common end of all . Poems is . to make those events which in real or imagined History move in a strait [sic] Line, assume to our Understandings a circular motion” (CL 4: 545). Coleridge’s so-called “Conversation” poems seem to conform most conspicuously to this aesthetic theory, structured as they are to return to their starting points at their conclusions. The assumption, however, that this comforting circular structure is commensurate with the sense of these poems can be questioned, for the conclusions of the “Conversation” poems are rarely, if ever, reassuring. The formal circularity of these poems is frequently achieved more by persuasive rhetoric than by any cohesion of elements. The circular structure encourages the reader’s expectations of unity and synthesis, but ultimately these expectations are disappointed, and instead the reader is surprised by an ending more troubling than the rhetoric of return and reassurance would suggest. Taking three “Conversation” poems as case studies (“The Eolian Harp,” “This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison,” and “Frost at Midnight”), this thesis attempts to explicate those tensions which exist in the “Conversation” poems between form and effect, between structure and sense.