Anish Kapoor Non-Object (Plane)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017-18 Annual Report St St Inveso Mundus (2015), AES+F, at Anand Warehouse, Mattancheri 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 Contents

Annual Report 2017-18 Annual Report st st Inveso Mundus (2015), AES+F, at Anand Warehouse, Mattancheri 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 Contents 06 Introduction 08 Kochi Biennale Foundation 10 Board of Trustees 12 Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018 Curator 14 Kochi Biennale Foundation Programmes 22 Fundraiser Auction 24 CSR Support and Kochi Biennale Foundation 24 Meeting of The Board of Trustees 24 Constitution of Internal Complaints Committee 26 Audit & Accountability 48 Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016 Sponsors, Patrons & Supporters Front Cover: Parayi Petta Panthirukulam (2016), PK Sadanandan, at Aspinwall House, Fort Kochi 4 5 Introduction On behalf of the trustees of the Kochi replicated across India. Kochi Biennale The respected Indian artist Anita Dube Biennale Foundation, I’m pleased to Foundation is honoured by the trust was announced as curator for the 2018 present the annual report of the activities placed in us by the government of Kerala. edition of the Biennale. She has begun her of the organisation for the year 2017-18. research for the fourth iteration. Anita is This contains a summary of our activities We are an organisation founded by expected to travel to around 30 countries this year, as well as the audited balance artists, led by artists, and curated by outside of India for research and discussion sheet for the financial year. artists. Without support from the artists towards her exhibition. Given the nature community in India and outside, the of her art practice and her capacities as a I feel that the Kochi-Muziris Biennale Biennale would be impossible. They critical thinker in the art-world, I have no has raised the bar for public cultural have been with the Foundation from doubt that she will put together a strong and programmes in India. -

0F5401520b5aa0736889b067d9

The Location of Culture ‘The work being done in my field, African and African-American Studies, is unimaginably richer because of Homi Bhabha’s stunning contribution to literary, historical, and cultural studies. The breadth and depth of his analysis, and the razor precision of his writing, push us all to be better, more innovative scholars, and I thank him for it.’ Henry Louis Gates, JR ‘The Location of Culture has been extraordinarily fertile for work in a variety of fields: literature, geography, architecture, politics among them. Homi Bhabha is at once radical and subtle in his method of argument and his insights have been fundamental to the flourishing of post-colonial studies.’ Gillian Beer, University of Cambridge ‘The Location of Culture is an exuberantly intelligent voyage of dis- covery and disorientation. Supple, subtle, and unafraid, its power lies in its remarkable openness to all that is challenging and unsettling in the contemporary world.’ Stephen Greenblatt, Harvard University ‘Bhabha is that rare thing, a reader of enormous subtlety and wit, a theorist of uncommon power. His work is a landmark in the exchange between ages, genres and cultures; the colonial, post-colonial, mod- ernist and postmodern.’ Edward Said ‘Homi Bhabha is one of that small group occupying the front ranks of literary and cultural theoretical thought. Any serious discussion of post-colonial/postmodern scholarship is inconceivable without refer- encing Mr Bhabha.’ Toni Morrison '\ L £ ~ () ~~ ct:o S Qrn r- • m • () ~ CI) ( m V ..q S 5 \ Routledge Classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have, by popular consent, become established as classics in their field. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

Engineering the Art of Anish Kapoor

ENGINEERING THE ART OF ANISH KAPOOR ESSAY BY CHRISTOPHER HORNZEE‐ JONES (Published with permission by the Solomon Guggenheim Museum New York) Design and engineering firm Aerotrope’s work on Anish Kapoor’s Deutsche Guggenheim commission is the latest in a series of close collaborations with the artist that began almost ten years ago. Over this period, we have contributed our technical expertise to the realization of his increasingly ambitious artworks in both public spaces and galleries, working with a diversity of materials from steel and wax to water and air, each of which has presented specific possibilities and challenges. I have been drawn to working with artists due to my long‐standing passion for creativity that spans the arts, design, engineering, and science. In our work outside of the art world, our role is often to evolve new designs and technology in the fields of renewable energy and experimental low‐energy vehicles. We see our work with artists as an integrated and enriching part of our practice, not as an interesting sideline to “real” work. The process of critically reexamining our received assumptions of what is possible and then formulating bold new expressions of vision is as vital to making compelling artworks as it is to adapting our society to the challenges of climate change and the limits of global resources. During each project with Kapoor, we may go through periods of relatively independent parallel work, which are linked by sessions of closely interactive review. Our objective, especially during the initial phase of realizing a new work, is to keep the creative options as open as possible rather than to let premature decision making, often driven by technical or production concerns, constrain or deflect Kapoor’s artistic judgments. -

Here in the United Online Premieres Too

Image : Self- portrait by Chila Kumari Singh Burman Welcome back to the festival, which this Dive deep into our Extra-Ordinary Lives strand with amazing dramas and year has evolved into a hybrid festival. documentaries from across South Asia. Including the must-see Ahimsa: Gandhi, You can watch it in cinemas in London, The Power of The Powerless, a documentary on the incredible global impact of Birmingham, and Manchester, or on Gandhi’s non-violence ideas; Abhijaan, an inspiring biopic exploring the life of your own sofa at home, via our digital the late and great Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee; Black comedy Ashes On a site www.LoveLIFFatHome.com, that Road Trip; and Tiger Award winner at Rotterdam Pebbles. Look out for selected is accessible anywhere in the United online premieres too. Kingdom. Our talks and certain events We also introduce a new strand dedicated to ecology-related films, calledSave CARY RAJINDER SAWHNEY are also accessible worldwide. The Planet, with some stirring features about lives affected by deforestation and rising sea levels, and how people are meeting the challenge. A big personal thanks to all our audiences who stayed with the festival last We are expecting a host of special guests as usual and do check out our brilliant year and helped make it one of the few success stories in the film industry. This online In Conversations with Indian talent in June - where we will be joined year’s festival is dedicated to you with love. by Bollywood Director Karan Johar, and rapidly rising talented actors Shruti Highlights of this year’s festival include our inspiring Opening Night Gala Haasan and Janhvi Kapoor, as well as featuring some very informative online WOMB about one woman gender activist who incredibly walks the entire Q&As on all our films. -

Anish Kapoor

ANISH KAPOOR Opening: Saturday, November 26th 2016, 6pm Open from Monday to Sunday, 10am-6pm. November 26, 2016 - March 26, 2017 ARTE CONTINUA is pleased to present A negative space for Kapoor does Anish Kapoor’s first solo exhibition not yield an absolute void. In in Cuba. Anish Kapoor is one of the fact, the artist states1: “The most significant artists of our void does not really exist because times. His work is distinguished by we are constantly filling it with its boundless capacity to reinvent our expectations and fears. artistic language, in its monumental My sculptures that are called dimension as in its more intimate one. empty objects therefore contain Likewise, from November 26, 2016, a possibility. They stimulate a to March 26, 2017, ARTE CONTINUA philosophical thought but are not will engage the public into a survey the answer to anything. They simply of suggestive polarities capable present a condition; you have to of affecting the way we perceive do the rest”. Kapoor’s research things. casts its fundaments in non-forms and auto-generated objects, man In May 2015, Anish Kapoor took and self-awareness, the mind and part in the XII Havana Biennial. In the experience of things, and the collaboration with Galleria Continua, universality of time and space. he submitted Wounds and absent objects, a site-specific installation The present exhibition project for the cinema-theater Payret. This was designed specifically for ARTE past November, at the exhibition CONTINUA Havana’s spaces. Its Follia Continua! 25 años de Galleria pace is set by five sculptures Continua, a collaboration between that investigate the relationship Galleria Continua and Centro de between fullness and the void. -

The Roles and Responsibilities of Museums in Civil Society

CIMAM 2017 Annual Conference Proceedings The Roles and Responsibilities of Museums in Civil Society CIMAM 2017 Annual Conference Proceedings Singapore 10–12 November 2017 1 CIMAM 2017 Annual Conference Proceedings Day 1 3 Day 3 56 Friday 10 November Sunday 12 November National Gallery Singapore National Gallery Singapore Art And The City: From Local To Transnational? What Do Museums Collect, And How? Keynote 1 4 Keynote 3 57 Nikos Papastergiadis Donna De Salvo Director, Research Unit in Public Cultures, Deputy Director for International Initiatives and Professor, School of Culture and and Senior Curator, Whitney Museum of Communication, University of Melbourne, American Art, New York, USA Melbourne, Australia Perspective 7 69 Perspective 1 13 Adriano Pedrosa Ute Meta Bauer Artistic Director, São Paulo Museum of Art, Founding Director, NTU Centre for São Paulo, Brazil Contemporary Art Singapore, Singapore Perspective 8 75 Perspective 2 18 Tiffany Chung Chen Chieh-Jen Artist, Vietnam/USA Artist, Taiwan Perspective 9 81 Perspective 3 24 Suhanya Raffel Andrea Cusumano Executive Director, M+, Hong Kong Deputy Mayor for Culture of Palermo, Italy Speakers Biographies 86 Day 2 27 Colophon 90 Saturday 11 November National Gallery Singapore Re-Learning Southeast Asia Keynote 2 28 Patrick D. Flores Professor of Art Studies, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines Perspective 4 40 Ade Darmawan Artist, Curator and Director, ruangrupa, Jakarta, Indonesia Perspective 5 45 Gridthiya Gaweewong Artistic Director, Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, Thailand Perspective 6 50 Post-Museum Jennifer Teo & Woon Tien Wei Artists, Singapore Note: Click on any of the items above to jump to the corresponding page. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

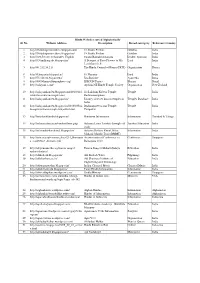

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Wired 2016.10.10.Indd

11 Ways to Make Your Office Complex Less Soul-Suckingly Awful October 10, 2016 | by Sam Lubell BRITISH DESIGNER THOMAS Heatherwick recently unveiled plans for Vessel—a beehive-shaped artwork, comprised of 154 interconnected flights of stairs, at the center of the 17-million square foot Hudson Yards development in New York City. The steel-framed piece, which widens as it ris- es, will lift visitors 150-feet into the air, offering a unique vantage of the place. Heatherwick says he designed it to differentiate what promises to be a bold, yet familiar, glassy contemporary office complex. “In recent decades we have had more and more global similarity. An office building in the arctic circle is not likely to be very different from an office in a tropical context. There are some great new buildings here, but they feel similar when you build them similarly and fill them with familiar con- tents,” Heatherwick says. Hudson Yards isn’t the only sleek corporate complex confronting the problem of same-ness. Archi- tects, artists, planners, and landscape architects around the world are creating increasingly weird and original focal points to set these environments apart. These include large-scale public art pieces, parks, and astonishing architectural elements. If corpo- rations are people, shouldn’t their lives be a little more interesting? 01: Amazon Biodomes Amazon’s new campus in downtown Seattle consists of three, 36-story glass towers that don’t look too different from other corporate buildings. But the complex is focused around something much more unique: three steel-framed and glass-clad “biospheres,” filled with plants and trees that are nicknamed “Bezos’ Balls,” for Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

A Lasting Engagement: the Jane and Kito De Boer Collection

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK - MUMBAI | 17 DECEMBE R 2019 | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A Lasting Engagement: The Jane and Kito de Boer Collection MORE THAN 150 WORKS OF MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY INDIAN ART AT AUCTION PREVIEWS IN INDIA: 9-12 JANUARY IN MUMBAI 31 JANUARY – 1 FEBRUARY IN NEW DELHI PREVIEW IN NEW YORK: 13-17 MARCH AT CHRISTIE’S ROCKEFELLER CENTER AUCTIONS IN NEW YORK: 18 MARCH IN NEW YORK – LIVE AUCTION 13-20 MARCH – ONLINE AUCTION New York/Mumbai: During New York’s annual Asian Art Week in March 2020, Christie’s announces an additional single-owner auction, A Lasting Engagement: The Jane and Kito de Boer Collection, offering more than 150 works of Indian art from the prestigious collection of Jane and Kito de Boer. This is the largest and most important single owner sale of South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art that Christie’s has had the pleasure to announce in this field in the last few years. A live auction, which will take place on 18 March, will be accompanied by an online sale, offering additional works from the collection between 13-20 March. A strong selection of highlights will be on view at Christie’s India representative office during Mumbai Gallery Weekend, taking place from 9 to 12 January, and then exhibited at a preview at the Oberoi Hotel in New Delhi on 31 January and 1 February, coinciding with the India Art Fair. Speaking about their collection, Jane and Kito de Boer noted, “We purchased our first paintings on impulse. These were an emotional response, reflecting our excitement at the vibrancy and energy of India’s culture. -

Gktoday May (1-31) 1

Page 1 of 117 GKTODAY MAY (1-31) 1. Who is the author of the “Politics of Jugaad: The Coalition Handbook”? (Marks: 0) Saba Naqvi Madhu Trehan Shereen Bhan Patricia Mukhim The “Politics of Jugaad: The Coalition Handbook” has been authored by journalist Saba Naqvi. In it, the author examined the possibility of a coalition government after 2019 Lok Sabha polls. It traces the history of political alliances in the country taking into account their performance on economic and and social policies, among others. The book also makes a study of the Congress' "tryst with dynasty" with Priyanka Gandhi Vadra taking a plunge into active politics for the party helmed by her brother Rahul Gandhi. 2. The Belt and Road Forum (BRF - 2019) was recently held in which of the following Chinese cities? (Marks: 0) Tianjin Shanghai Beijing Hangzhou In China, the 2nd edition of Belt and Road Forum (BRF - 2019) was officially held in Beijing with theme “Belt and Road Cooperation: Shaping a Brighter Shared Future”. In it, 37 heads-of-state and 159 countries had participated along with United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and International Monetary Chief (IMF) Christine Lagarde. The BRF is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The aim of BRI is to reinvent the ancient Silk Road to connect Asia to Europe and Africa through massive investments in maritime, road and rail projects. The initiative offers to bring much-needed modern infrastructure to developing countries, but critics say it mainly favours Chinese companies while saddling nations with debt and causing environmental damage.