Thomas Berry: Reflections on His Life and Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Moment Is Now

173 Our Moment Is Now Ambassador Melanne Verveer and Kim Azzarelli In 1848, Charlotte Woodward was earning a pittance stitching gloves in her home in Waterloo, New York.1 Like other women of her era, the former schoolteacher, not yet twenty years old, had been denied prop- erty ownership rights, citizenship, and political representation. In some states, if a woman married, everything she owned or earned belonged to her husband. That July, Woodward was intrigued by an announcement she read in the newspaper about a meeting of women to be held in a chapel forty miles away, in the town of Seneca Falls. Looking for an opportunity to better her life and that of her family, she did what women have done throughout history and to this day: she joined a network. Woodward’s experience and those of others contextualize the movement for women’s rights and equal participation from a historical perspective, both in the Ambassador Melanne Verveer serves as the Co-Founder of Seneca Women and Executive Director of Georgetown University›s Institute for Women, Peace and Security. She is co-author with Kim Azzarelli of the new book Fast Forward: How Women Can Achieve Power and Purpose and a Founding Partner of Seneca Point Global. In 2009 President Obama appointed Melanne Verveer to be the first ever Ambassador- at-Large for Global Women’s Issues at the U.S. State Department. Ambassador Verveer has a B.A. and M.A. from Georgetown University. She is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and has served as the 2013 Humanitas Visiting Professor at Cambridge University. -

Reciu'rernents F°R ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV

THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC A written work submitted to the faculty of ^ ^ San Francisco State University - 7 ' In partial fulfillment of 7o l£ RecIu'rernents f°r ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV Master of Arts In English: Creative Writing By Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Miah Joseph Jeffra 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Violence Almanac by Miah Joseph Jeffra, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written creative work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Arts in English: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Professor of Creative Writing THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California 2018 The Violence Almanac addresses the relationships between natural phenomena, particularly in geology and biology, and the varied types of violence experienced in American society. Violence is at the core of the collection—how it is caused, how it effects the body and the body politic, and how it might be mitigated. Violence is also defined in myriad ways, from assault to insult to disease to oppression. Many issues of social justice are explored through this lens of violence, and ultimately the book suggests that all oppressive forces function similarly, and that to understand our nature is to understand our culture, and its predilection for oppression. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. ' Chair, Written Creative Work Committee Date ACKNO WLEDG EMENT Thank you to Lambda Literary, Ragdale and the Hub City Writers Project, for allowing me the space to write these stories. -

Biography of Thomas Berry

Biography of Thomas Berry Mary Evelyn Tucker Yale University (Prepared in 2009) To fully understand Thomas Berry's presentation of the New Story it is helpful to highlight some of the major intellectual influences on his life and thinking. In this way we can more fully appreciate the nature and significance of the New Story itself. In this intellectual biography we will first discuss Berry's studies of western history, Asian traditions, and indigenous religions. We will then describe the early and sustained influence of PierreTeilhard de Chardin on Berry's philosophy of evolutionary history. Finally, we will outline some of the major features of the New Story as Berry has described it. From human history to Earth history It is significant to see Berry's contributions initially as a cultural historian whose interests have spanned both Europe and Asia. He did his graduate studies in western history and spent several years living in Germany after the Second World War. In addition, he read extensively in the field of Asian religions and history. He lived in China the year before Mao came to power and published two books on Asian religions, which have been reissued from Columbia University Press (Buddhism and Religions of India). From this beginning as a cultural historian Berry has moved in the last twenty years to become a historian of Earth. Berry sees himself, then, not as a theologian but as a geologian. The movement from human history to cosmological history has been a necessary progression for Berry. He has witnessed in his own life time the emergence of a planetary civilization as cultures have come in contact around the globe, often for the first time. -

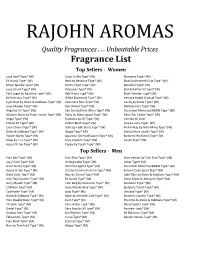

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Fragrance List 2016

FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 1 Fragrance List 2016 Family Owned & Operated FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 2 LUXURY TUBING ROLLON MEET YOUR OILS NEW BEST FRIENDS B0010 B0011 Starting at only $5.99/Dozen 1 FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 3 LatestLatest FragrancesFragrances PDCT# PRODUCT NAME 1 OZ 2 OZ 4 OZ 8 OZ 1 LB F1530 Always Red For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1557 Amor Amor For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1549 Amor Amor For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1543 Aramis Black For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1515 Ariana Grande Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1561 Bebe Glam Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1511 Black Axe For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1532 Bold For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1535 Born Original For Her Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1536 Born Original For Him Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1559 Br Wildbloom For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1548 Cabotine Fleur De Passion Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1544 Cabotine For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1542 Chrome Intense For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1513 D&G Exotic Leather Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1514 D&G Velvet Love Women Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1554 Decadence For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1527 Dior Sauvage For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1497 Fire & Ice For Men Type $4.95 $9.00 -

Initiative for a Competitive Brooklyn: Seizing Our Moment

Initiative For A Competitive Brooklyn: Seizing Our Moment Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation Initiative for a Ron Melichar, Director of District Marylin Gelber, Executive Patrick Condren, Management Competitive Brooklyn Management Services and Director, Independence Consultant, Travel/Transportation Committees and Teams Investment, NYC Department of Community Foundation & Economic Development Small Business Services Colvin Grannum, Director, Executive Committee Ellen Oettinger, Economic Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Action Team: Food Processing Development Specialist, Corporation Co-chairs: Co-chairs: Brooklyn Borough Hall Bill Grinker, Chairman, Seedco Adam Friedman, Executive Stanley Brezenoff, President and Dan Wiley, Congresswoman Edison Jackson, President, Director, New York Industrial CEO, Continuum Health Partners Nydia Velazquez’s Office, Medgar Evers College Retention Network Hon. Marty Markowitz, U.S. House of Representatives Stuart Leffler, Manager of Bill Solomon, Owner, Brooklyn Borough President Economic Development for Serengeti Consulting Strategy Board Brooklyn, ConEd Members: Hon. Jim Brennan, New York Jeanne Lutfy, President, Brooklyn Action Team: Health Services Kenneth Adams, President, State Assemblyman Academy of Music LDC Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce Co-chairs: Jonathan Bowles, Research Regina Peruggi, President, Norman Brodsky, President, Director, Center for an Stanley Brezenoff, President and Kingsborough Community CitiStorage Urban Future CEO, Continuum Health Partners College Maurice Coleman, Senior -

Creation Spirituality and Lutheranism Marilyn Jackson and Notes from a Presentation by Larry Rasmussen Augustana Heritage Gathering Rock Island, IL, June, 2010

Creation Spirituality and Lutheranism Marilyn Jackson And Notes from a Presentation by Larry Rasmussen Augustana Heritage Gathering Rock Island, IL, June, 2010 Part I: Presentation by Marilyn Jackson, PhD, Western Institute for Social Research, Berkeley, CA; Augustana BA, religion major graduate and MA graduate of Institute in Culture and Creation Spirituality, Holy Names College, Oakland, CA Introduction to Creation Spirituality as defined by Matthew Fox: As a young Catholic priest, in the 1960s, Matthew Fox was concerned about the flocking of his peers to Eastern Spirituality. He set out to discover what “Western Spirituality” had to offer. He developed Creation Spirituality, which includes any religion that holds earthly creation to be a dynamic, creative subject of our spiritual belief. Fox studied at graduate school in Paris , France, where Pere (Father) Chenu, named the "creation centered" vs. "fall/ redemption" spiritual traditions for him. He then developed an institute for the study of Western Spiritual traditions that took a few different forms in recent decades. Spirituality is a newer term for Lutherans than for Catholics. For many it means an inner experience but this inner work leads to a difference in one’s outer life as well. Mysticism is a similar word, often thought of as unrelated to every day life, though that is a narrow view, because as we change inside, it naturally changes what occurs in our outward lives. Matthew Fox expanded the definition for the terms of spirituality, mysticism and religious experience, to include art as meditation, seeing the activity of creation happening in creativity and artistic endeavor. He linked the concept of transformation and social justice. -

A Prophetic Voice: Thomas Berry

A PROPHETIC VOICE: THOMAS BERRY By Marjorie Hope and James Young Introduction Whenever Thomas Berry looks out over the Hudson River from his home at the Riverdale Center for Religious Research, he experiences anew “the gorgeousness of the natural world.” The Earth brings forth a display of beauty in such unending profusion, a display so overwhelming to human consciousness, he says, that “we might very well speak of it as being dreamed into existence.” But this Passionist priest and cultural historian—who calls himself a geologian—also reflects on the disastrous damage humans have wrought on the Earth. What is happening today is unprecedented, it is not just another change, he says. We are changing the very structure of the planet. We are even extinguishing many of the major life systems that have emerged in the 65 million years of this, the Cenozoic era—an era that has witnessed a spectrum of wonders, including the development of flowers, birds, and insects, the spreading of grasses and forests across the land, and the emergence of humans. The Earth is changing, and we ourselves, integral aspects of the Earth, are being changed, he says. Religion must now function within this context, at this order of magnitude. But Western religion has been assuming little or no responsibility for the state or fate of the planet. Theology has become dysfunctional. As a member of a Roman Catholic order, Berry directs much of his criticism at the tradition he knows best, Christianity. But his intention is to address people of any belief, and his searching mind and wide acquaintance with Chinese, Indian, Southeast Asian, Native American, and other cultures ‐ indeed, the entire pageant of cultural history ‐ make him catholic in the, non‐ sectarian sense of the term. -

Contemplation and Cosmology Readings and Films

Fall 2019 Contemplation and Cosmology Readings and Films Homework for Week 2 Readings in preparation for Week 2 2-1 “The Lens Through Which We See” by Joe Mitchell 2-2 “The Meadow Across the Creek” by Thomas Berry, from The Great Work: Our Way into the Future, Chapter 2 Internet viewing 1. Watch: “The New Story” with Brian Swimme, located on YouTube at Brian Swimme Video Series: “Swimme 1: The New Story” (6:48) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRykk_0ovI0 Extra Credit (if you have the interest and time) Journey of the Universe (the text book we are using for Med 3) has a website with additional information. https://www.journeyoftheuniverse.org/ Big History Project – The Big History Project was started by Bill Gates and David Christian to enable the global teaching of the subject of Big History, which is described as “the attempt to understand, in a unified way, the history of Cosmos, Earth, Life and Humanity.” https://school.bighistoryproject.com/bhplive For background on Thomas Berry, explore his website www.thomasberry.org. There you can find many essays and videos of his lectures. Homework for Week 3 Readings in preparation for Week 3 3-1 “The New Story” by Thomas Berry 3-2 “Turning Point: A Science of Living Systems” by Fritjof Capra Internet viewing 1. Watch “The History of Our World in 18 Minutes” a TED talk by David Christian (17:40) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqc9zX04DXs 2. Watch “Ecology: A New Story” by Brian Swimme, lecture at Seattle University, available on YouTube (73:28) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qeX8Tzt8ur0 Homework for Week 4 Readings in preparation for Week 4 4-1 “How to Build a Universe” by Bill Bryson, from A Short History of Nearly Everything, Chapter 1 1“The Epic of Evolution” by Brian Swimme 4-2 “The Contemplative and the Cosmos” by Beatrice Bruteau, from God’s Ecstasy: The Creation of a Self- Creating World, Chapter 1 Internet viewing 1. -

BW Confidential Will Be Taking a Break for the Summer

www.bwconfidential.com The inside view on the international beauty industry July 10-August 27, 2014 #96 CONFIDENTIAL CONFIDENTIAL CONFIDENTIAL Comment Inside The buzz 2 Retail on fire News roundup obile shopping strategies are likely to get a little Netwatch 6 Mmore serious now that Amazon has launched its own smartphone. The e-commerce giant’s Fire Beauty blogger review Phone is described as more of a shopping tool than a communication device, as it can recognize thousands Interview 7 of products and enable users to immediately buy them Givaudan fragrance division from Amazon’s website. The phone’s dedicated button president Michael Carlos for making a purchase means that shoppers have more opportunities to shop and shop more easily and Insight 9 can compare prices and buy an item that costs less India on Amazon. This is likely to send shivers down the spine of most competing retailers, but could be a major opportunity for brands to sell more if they agree to Show review cooperate with Amazon. World Perfumery Congress 12 Amazon practically invented e-commerce, transforming (and in some cases MakeUp in Paris 14 destroying) a string of industries from book selling to electronics retail in the process. Its new phone could very well usher in another new chapter in retailing. Store visit 16 It’s unlikely that beauty will remain untouched by the online retailer’s ever- ArtDeco, Paris growing influence for long. Industry players may have to decide sooner than they thought whether they can beat Amazon with their own strategies or whether they will end up having to join them. -

Wood-Working Draft

(To be published in the forthcoming issue of the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy & Environmental Law Review) Atmospheric Trust Litigation: Securing a Constitutional Right to a Stable Climate System* Mary Christina Wood† It is a privilege to be here in Boulder, which is a place I think of as a hub of climate action, with its young climate warriors, its renewable energy visionaries, and its dedicated league of citizens determined to create a safe future. And it is a supreme honor to give the lecture named after the two legal giants who have so shaped Indian law, natural resources law, and public lands law with their brilliant vision and dedication to justice. My honor is magnified by the immense gratitude I have towards Professor Charles Wilkinson, who has been an invaluable mentor and guiding light throughout my entire teaching career. He is the person who, in an unparalleled way, steps back from the law as it appears in the moment and contextualizes it in history, recognizing and identifying its organizing force through the ages. He is the one who captures the essence of legal principles and their driving rationale and inspires us all to reach towards the law no matter how daunting the challenge we face. It was largely his scholarship that led me into the heart of the public trust doctrine many years ago. I. This evening I will describe a litigation campaign and strategy that draws upon this public trust principle to confront the climate emergency. Let us begin with a simple recognition that we are the living beneficiaries of a public trust—a priceless trust. -

Head, Heart, Hands

PRESIDENT’S ESSAY head, heart, hands Dr. Stephen R. Briggs The purpose of Berry HE HEADLINES ARE BERRYRELENTLESS: undertaking all manner of work necessary to differences. This practical learning occurs in “College costs too much,” “How sustain the institution, from growing crops, the residence halls, on the playing fields, in TLiberal Arts Colleges Are Failing tending livestock and preparing food to work settings, with work teams, with study America,” “The Campus Tsunami,” “The constructing the buildings in which they groups, and in the classroom. Learning how future of online vs. residential education,” lived, worked and studied. Martha intended to improve Berry as a campus community and “Come the Revolution.” to break the cycle of poverty in the hill provides a practical and principled lesson in Two articles landed on my desk recently. country of Northwest Georgia by investing in how to improve any community. One was titled “The End of the University as educated and morally sound families who Berry is also part of an extended commu- We Know It.” Its central claim was that with would become the foundation for strong nity, the commu nity of Rome and Floyd major universities providing access to free rural communities. County. Berry’s health and continued prosperity online lectures, half of America’s universities Martha sought out deserving and talented are contingent on the well-being of this larger will be closed in 50 years and “ten years boys and girls who had “sparkle in their neighborhood. Thus, Berry has a vested interest from now Harvard will enroll ten million eyes,” but her goal was not simply or in improving the community in which it students.” The logic is that “the Internet is a primarily to advance their eventual success resides by promoting economic development, great destroyer of any traditional business and prosperity.