Alfred Jarry: a Pataphysical Life by Alastair Brotchie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture's Ephemeral Practices

____________________ A PATAPHYSICAL READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE ______183 A “PATAPHYSICAL” READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE Mary Vaughan Johnson Virginia Tech The Maison de Verre (1928-32) is a glass-block the general…(It) is the science of imaginary house designed and built by Pierre Chareau solutions...”3 According to Roger Shattuck, in (1883-1950) in collaboration with the Dutch his introduction to Jarry’s Exploits & Opinions architect Bernard Bijvoët and craftsman Louis of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, “(i)f Dalbet for the Dalsace family at 31, rue St. mathematics is the dream of science, ubiquity Guillaume in Paris, France. A ‘pataphysical the dream of mortality, and poetry the dream reading of the Maison de Verre, undoubtedly of speech, ‘pataphysics fuses them into the one of the most powerful modern icons common sense of Dr. Faustroll, who lives all representing modernism’s alliance with dreams as one.” In the chapter dedicated to technology, is intended as an alternative C.V. Boys, Jarry, for instance, with empirical history that will yield new meanings of precision, describes Dr. Faustroll’s bed as modernity. Modernity in architecture is all too being 12 meters long, shaped like an often associated with the constitution of an elongated sieve that is in fact not a bed, but a epoch, a style developed around the turn of boat designed to float on water according to the 20th century in Europe albeit intimately tied Boys’ principles of physics.4 The image of a to its original meaning related to an attitude boat that is also a bed, at the same time, towards the passage of time.1 To be truly brings to mind the poem by Robert Louis modern is to be in the present. -

Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts Paintings, Drawings, Calligrammes

! 44a Charlotte Road, London, EC2A 3PD Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts paintings, drawings, calligrammes 4 November - 16 December 2016 ____________________ Private View: 3 November 6.30 - 8.30 pm Calligramme XXIII (‘fossil’),1961 (?), Black, gold and red paint on paper, 52 x 63.5cm, © Themerson Estate, courtesy of l’étrangère. " It seemed to me that the interrelation between these two sides: order in nature on the one side, and the human condition on the other, was the undefinable drama to be grasped, dealt with and communicated by me. - Franciszka Themerson, Bi-abstract Pictures, 1957 l’étrangère is delighted to present a solo exhibition of paintings, drawings and calligrammes by Franciszka Themerson - a seminal figure in the Polish pre-war avant-garde. She developed her unique pictorial language during the shifting years of pre- and post-war Europe, having settled in Britain in 1943. Together with her husband, writer, poet and filmmaker, Stefan Themerson, she was involved with experimental film and avant-garde publishing. Her personal domain, however, focused on painting, drawing, theatre sets and costume design. This exhibition brings together Franciszka’s three paintings completed in 1972 and a selection of drawings, dated from 1955 to 1986, which demonstrate the breadth of her work. ! The paintings: Piétons Apocalypse, A Person I Know and Coil Totem, act as anchors in the exhibition, while the drawings demonstrate the variety of motifs recurring throughout her work. The act of drawing and the key role of the line remain a constant throughout her practice. The images are characterised by a fluidity of line, rhythmic composition and the humorous depiction of everyday life. -

Anthropoetics XX, No. 2 Spring 2015

Anthropoetics XX, 2 Anthropoetics XX, no. 2 Spring 2015 Peter Goldman - Originary Iconoclasm: The Logic of Sparagmos Adam Katz - An Introduction to Disciplinarity Benjamin Matthews - Victimary Thinking, Celebrity and the CCTV Building Robert Rois - Shared Guilt for the Ambush at Roncevaux Samuel Sackeroff - The Ends of Deferral Matthew Schneider - Oscar Wilde on Learning Outcomes Assessment Kieran Stewart - Origins of the Sacred: A Conversation between Eric Gans and Mircea Eliade Benchmarks Download Issue PDF Subscribe to Anthropoetics by email Anthropoetics Home Anthropoetics Journal Anthropoetics on Twitter Subscribe to Anthropoetics RSS Home Return to Anthropoetics home page Eric Gans / [email protected] Last updated: 11/24/47310 12:58:33 index.htm[5/5/2015 3:09:12 AM] Goldman - Originary Iconoclasm Anthropoetics 20, no. 2 (Spring 2015) Originary Iconoclasm: The Logic of Sparagmos Peter Goldman Department of English Westminster College Salt Lake City, Utah 84105 www.westminstercollege.edu [email protected] The prohibition of "graven images" in the Jewish scriptures seems to have no precedent in the ancient world. Surrounded by polytheistic religions populated with a multitude of religious images, the ancient Hebrews somehow divined that the one true God could not be figured, and that images were antithetical to his worship. It's true, of course, and significant, that every known culture has taboos regarding representations qua representations, often but not exclusively iconic figures.(1) But only the Hebrews derived a prohibition on images from the recognition that God is both singular and essentially spiritual, hence resistant to material representation.(2) In the ancient world, images were connected to the divine, either as the privileged route to god's presence, both dangerous and desirable; or as forbidden temptations to idolatry, the worship of "false gods," however defined. -

Ubu Roi Short FINAL

media contact: erica lewis-finein brightbutterfly[at]hotmail.com CUTTING BALL THEATER CONTINUES 15TH SEASON WITH “UBU ROI” January 24-February 23, 2014 In a new translation by Rob Melrose SAN FRANCISCO (December 16, 2013) – Cutting Ball Theater continues its 15th season with Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI in a new translation by Rob Melrose. Russian director Yury Urnov (Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company) helms this irreverent take on world leaders. Featuring David Sinaiko, Ponder Goddard, Marilet Martinez, Bill Boynton, Nathaniel Justiniano, and Andrew Quick, UBU ROI plays January 24 through February 23 (Press opening: January 30) at the Cutting Ball Theater in residence at EXIT on Taylor (277 Taylor Street) in San Francisco. For tickets ($10-50) and more information, the public may visit cuttingball.com or call 415-525-1205. When Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI premiered in Paris on December 10, 1896, the audience broke into a riot at the utterance of its first word. Jarry’s parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth defies theatrical tradition through its disregard for audience expectations, replacing Shakespeare’s tragic hero with a greedy, sadistic ogre who becomes the King of Poland by force and through the debasement of his people. Set in a modern luxury kitchen, this re-visioned UBU ROI features a wealthy American couple who play out their fantasies of wealth and power to excess as they take on the roles of Mother and Father Ubu. Cutting Ball’s version of UBU ROI may bring to mind the fall from grace of many a contemporary political leader corrupted by power, from Elliot Spitzer to Dominique Strauss-Kahn. -

Alfred Jarry's Semantics : a Web of Disambiguation, Mirrors, Energy, Machines, and Potential Collisions

Alfred Jarry's Semantics : a web of disambiguation, mirrors, energy, machines, and potential collisions Linda Klieger Stillman [email protected] Abstract—This paper was given at www2016, Montreal, In order to unpack the links and the leaps that connect Jarry’s Canada, April 2016 iconoclasm and semioclasm, at the time when typewriters were becoming more widely used, to our era of bits and bytes Keywords—web; disambiguation; pataphysics; energy; of information traveling from similar keyboards in a digital machines age, Jarry’s definition of ’Pataphysics is ground zero. Defined by Jarry most rigorously and painstakingly in Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, neo scientific novel, [2] he begins his definition of ’Pataphysics by specifying that “An epiphenomenon is that which is superinduced upon a phenomenon…” and he continues with the ground-breaking assertion that it “is the science of that which is superinduced upon metaphysics, whether within or beyond the latter’s limitations, extending as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics. Ex: an epiphenomenon being often accidental, pataphysics will be, above all, the science of the particular, despite the common opinion that the only science is that of the general. Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain IMAGINATION WWW’P the universe supplementary to this one; or, less ambitiously, will describe a universe which can be—and perhaps should be—envisaged in the place of the traditional one, since the Alfred Jarry, in his -

Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014

Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014 Izdaja | Published by Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA Ljubljana 2014 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 141.7(082) 7.036(082) MODERNISM revisited / edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller. - Ljubljana : Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU = Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA, 2014. - (Filozofski vestnik, ISSN 0353-4510 ; 2014, 2) ISBN 978-961-254-743-1 1. Erjavec, Aleš, 1951- 276483072 Contents Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Volume XXXV | Number 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Editorial 13 Sascha Bru The Genealogy-Complex. History Beyond the Avant-Garde Myth of Originality 29 Eva Forgács Modernism's Lost Future 47 Jožef Muhovič Modernism as the Mobilization and Critical Period of Secular Metaphysics. The Case of Fine/Plastic Art 67 Krzysztof Ziarek The Avant-Garde and the End of Art 83 Tyrus Miller The Historical Project of “Modernism”: Manfredo Tafuri’s Metahistory of the Avant-Garde 103 Miško Šuvaković Theories of Modernism. Politics of Time and Space 121 Ian McLean Modernism Without Borders 141 Peng Feng Modernism in China: Too Early and Too Late 157 Aleš Erjavec Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge 175 Patrick Flores Speculations on the “International” Via the Philippine 193 Kimmo Sarje The Rational Modernism of Sigurd Fosterus. A Nordic Interpretation 219 Ernest Ženko Ingmar Bergman’s Persona as a Modernist Example of Media Determinism 239 Rainer Winter The Politics of Aesthetics in the Work of Michelangelo Antonioni: An Analysis Following Jacques Rancière 255 Ernst van Alphen On the Possibility and Impossibility of Modernist Cinema: Péter Forgács’ Own Death 271 Terry Smith Rethinking Modernism and Modernity 321 Notes on Contributors 325 Abstracts Kazalo Filozofski vestnik Ponovno obiskani modernizem Letnik XXXV | Številka 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Uvodnik 13 Sascha Bru Genealoški kompleks. -

ABBAYE Livres

GEOFFROY J.-R. et BEQUET Y. S.VV Commissaires-Priseurs Habilités ROYAN, 6, Rue R. Poincaré, (17207 ) Tél: 05.46.38.69.35 -Fax: 05.46.39.28.05 E-mail : [email protected] SAINTES , 38 Bld Guillet-Maillet (Bureau annexe) Tél: 05.46.93.39.14 E-mail : [email protected] ,N° d’agrément 2002-204 VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES Jeudi 7 Décembre à 11h15 (Lots 1 à125) Jeudi 7 Décembre à 14h15 (Lots 125à fin) Abbaye aux Dames 17100 Saintes LIVRES et AUTOGRAPHES Expositions : Mercredi 6 Décembre de 14h à 19h et Jeudi 7 Décembre de 9h à 11h Expert Christine CHATON – 3, rue Gautier – 17100 Saintes Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés (C.N.E.S.) Tél : 06.08.92.27.75 / Fax : 09.81.70.96.13 / [email protected] : LISTE Vente du matin (11h15) 1 1. ALMANACHS & ÉTRENNES. XVIIIe - XIXe s. Réunion d’une trentaine de volumes 250 350 dont : - Le Meilleur Livre ou Les meilleures Etrennes que l’on puisse donner et recevoir. Paris, Prault, 1745. Cart. papier gaufré avec motifs doré. Etat moyen. - Calendrier de la Cour. (1764). In-32, reliure maroquin brun. - Les Spectacles de Paris ou Calendrier … des Théâtres (1770). - Étrennes Intéressantes (1780, An VI, An VIII, 1816), avec étuis. - Étrennes Nouvelles, commodes et utiles, imprimées par ordre de son Eminence Monseigneur le Cardinal de La Rochefoucauld… à l’usage de son diocèse. Rouen, Seyer, 1783. In-16, reliure veau brun (usagée). - Almanach des Muses (1783). In-12, broché. Pas de page de titre. - Calendrier du Limousin (Barbou, 1787). -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I am using the terms ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Michel de Certeau’s sense, in that ‘space is a practiced place’ (Certeau 1988: 117), and where, as Lefebvre puts it, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’ (Lefebvre 1991: 26). Evelyn O’Malley has drawn my attention to the anthropocentric dangers of this theorisation, a problematic that I have not been able to deal with fully in this volume, although in Chapters 4 and 6 I begin to suggest a collaboration between human and non- human in the making of space. 2. I am extending the use of the term ‘ extra- daily’, which is more commonly associated with its use by theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe the per- former’s bodily behaviours, which are moved ‘away from daily techniques, creating a tension, a difference in potential, through which energy passes’ and ‘which appear to be based on the reality with which everyone is familiar, but which follow a logic which is not immediately recognisable’ (Barba and Savarese 1991: 18). 3. Architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton distinguishes between the ‘sceno- graphic’, which he considers ‘essentially representational’, and the ‘architec- tonic’ as the interpretation of the constructed form, in its relationship to place, referring ‘not only to the technical means of supporting the building, but also to the mythic reality of this structural achievement’ (Frampton 2007 [1987]: 375). He argues that postmodern architecture emphasises the scenographic over the architectonic and calls for new attention to the latter. However, in contemporary theatre production, this distinction does not always reflect the work of scenographers, so might prove reductive in this context. -

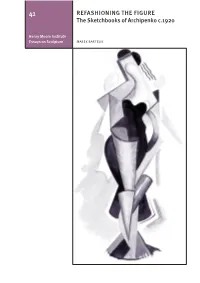

REFASHIONING the FIGURE the Sketchbooks of Archipenko C.1920

41 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920 Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture MAREK BARTELIK 2 3 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.19201 MAREK BARTELIK Anyone who cannot come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate…but with his other hand he can note down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different (and more) things than the others: after all, he is dead in his own lifetime, he is the real survivor.2 Franz Kafka, Diaries, entry on 19 October 1921 The quest for paradigms in modern art has taken many diverse paths, although historians have underplayed this variety in their search for continuity of experience. Since artists in their studios produce paradigms which are then superseded, the non-linear and heterogeneous development of their work comes to define both the timeless and the changing aspects of their art. At the same time, artists’ experience outside of their workplace significantly affects the way art is made and disseminated. The fate of artworks is bound to the condition of displacement, or, sometimes misplacement, as artists move from place to place, pledging allegiance to the old tradition of the wandering artist. What happened to the drawings and watercolours from the three sketchbooks by the Ukrainian-born artist Alexander Archipenko presented by the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a poignant example of such a fate. Executed and presented in several exhibitions before the artist moved from Germany to the United States in the early 1920s, then purchased by a private collector in 1925, these works are now being shown to the public for the first time in this particular grouping. -

EC V17N2 093.Pdf

ARTf CULOS RE SENA POEMS BY MANUEL ALVAREZ ORTEGA, BETWEEN MODERNISM AND THE METAPHYSICAL TRADITION FRANCISCO Ruiz SORIANO Poems (2000) by Manuel Alvarez Ortega is a selection of writ- ings edited by Margarita Prieto in Antelia Publishers. The poems were translated into English by Louis Bourne and appeared, for the first time in the International Journal of Poetry, Issue number 2, Spring, 1982. The six poems belong to the book Gesta also published in 1982. Manuel Alvarez Ortega, born in Cordoba in 1923, is one of the most important poets of the post-war Spanish generation. He founded and edited the literary review Aglae in 1949, a progres- sive and liberal journal that was open to poetry with avant-garde tendencies. In this review he publicized the latest French poets whom he also translated into Spanish. His much accomplished translations of Modern French poetry also give him great impor- tance on the literary scene. These include not only the antholo- gies Poesia simbolista francesa (1975), and his recently published book Veinte poetas franceses del siglo XX (2001), but also his work on individual poets such as Andre Breton, Lautreamont, Jules Laforgue, Alfred Jarry, Apollinaire, Paul Eluard, Victor Segalen, Patrice de la Tour du Pin among others. The poetry of Alvarez Ortega falls within the Modern Europe- an movements. For instance he was inspired from outside sources that lead him to re-work worn-out topics with the vision of a Spanish writer who had suffered the consequences of the Civil War and Franco's dictatorship, inner exile and oppression. While other poets returned to a poetry with Neoclassical patterns or a - 93 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA poetry of social protest, which meant the establishment of the tutelage of Antonio Machado or Juan Ramon Jimenez, represent- ing a stultifying imitation of fashionable models, Alvarez Ortega was revitalizing the entire Spanish literary scene with his poetry of imagination and vivid metaphor. -

Douglas Kahn

This essay is based on a talk given at the symposium, "Static and Interference : The Cultural Politics of Alternative Music", at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 24 April 1988 . First publication - Art & Text -Sydney) A Better Parasite Douglas Kahn In English there are two general meanings for the word parasite : biological parasites and social parasites . The French have a third : static . In a symposium named Static and Interference, in other words, there's something unspoken lurking in the title, a bug in the metaphors . Static, interference -- these words connote transgression ; the parasite is a helpful reminder that transgression is fueld by sucking . Lately, however, transgression has become genteel, a parasite that grooms its host . Abrasion exists but it won't wear away your teeth ; movement exists but it grows static . There's a better parasite to be had and a fat place for it to leech : the avant-garde . Although it isn't predominantly music this parasite promises rehabilitation if not rejuvenation for alternative music by working toward new arts of sound in general . Alternative music just has to learn how to exploit better .1 The favored transgressive elements within alternative music - noise, pastische and quotation, sampled and recorded sound - contain within them impulses for other arts of sound . The demise of blatant noi=se, the impasse in the use of recorded sound, and the currency of nostalgic pastiche, indicate the pervasive inability to usher these elements past the problematic of music . They rely on some sen=se of extra-musicality, a sign of worldly sound and of the incorporation of the world . -

Mise En Page 1

BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. EDITIONSORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHESET MANUSCRITSDU XX E SIÈCLE MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 - SOTHEBY’S PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 Experts de la vente DOMINIQUE COURVOISIER Expert de la Bibliothèque nationale de France Membre du Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en œuvres d’art 5, rue de Miromesnil 75008 Paris Tél./Fax. + 33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 [email protected] ANNE HEILBRONN SOTHEBY’S 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré 75008 Paris Tél. +33 (0)1 53 05 53 18 Fax. +33 (0)1 53 05 52 23 [email protected] Tous nos remerciements à Monsieur Jean-Paul Goujon pour l’aide précieuse apportée à la rédaction des notices des manuscrits et des autographes MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 À 14H30 VENTE À PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHES ET MANUSCRITS DU XXE SIÈCLE Vente dirigée par Cyrille Cohen et Alexandre Giquello Agréments du Conseil des Ventes Volontaires de Meubles aux Enchères Publiques n° 2001-002 et n° 2002-389 EXPOSITION Vendredi 3 et samedi 4 octobre de 10h à 18h Lundi 6 octobre de 10h à 20h sothebys.com/bidnow 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré - 75008 Paris tél. 33 (0)1 53 05 53 05 www.sothebys.com SPÉCIALISTES RESPONSABLES DE LA VENTE Pour toute information complémentaire concernant les lots de cette vente, veuillez contacter les experts listés ci-dessous. RÉFÉRENCE DE LA VENTE ENCHÈRES TÉLÉPHONIQUES PF1453 “Médaillon” & ORDRES D’ACHAT +33 (0)1 53 05 53 48 Fax +33 (0)1 53 05 52 93/94 EXPERTS DE LA VENTE [email protected] Dominique Courvoisier Les demandes d’enchères +33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 téléphoniques doivent nous [email protected] parvenir 24 heures avant la vente.