Monitoring for Rats on the Uninhabited Island, St Helen's Winter 2016/17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in the Isles of Scilly

WALKING IN THE ISLES OF SCILLY 11 WALKS AND 4 BOAT TRIPS EXPLORING THE BEST OF THE ISLANDS by Paddy Dillon JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Paddy Dillon 2021 CONTENTS Fifth edition 2021 ISBN 978 1 78631 104 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................5 Location ..........................................................6 Fourth edition 2015 Geology ..........................................................6 Third edition 2009 Ancient history .....................................................7 Second edition 2006 Later history .......................................................9 First edition 2000 Recent history .....................................................10 Getting to the Isles of Scilly ..........................................11 Getting around the Isles of Scilly ......................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Latitude Press. Boat trips ........................................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Tourist information and accommodation ................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Maps of the Isles of Scilly ............................................17 The walks ........................................................18 Guided walks .....................................................19 Island flowers .....................................................20 © Crown copyright -

Isles of Scilly Marine Special Area of Conservation Management Scheme

ISLES OF SCILLY MARINE SPECIAL AREA OF CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT SCHEME Name: Isles of Scilly Complex Unitary Authority/County: Isles of Scilly SAC status: Designated on 1 April 2005 Grid reference: SV883111 SAC EU code: UK0013694 Area (ha): 26850.95 Printed: February 2010 Cover photos by Tim Allsop & Angie Gall Isles of Scilly Management Scheme 1 Photos by Tim Allsop Isles of Scilly Management Scheme 2 Contents SECTION NUMBER PAGE 1. Introduction 5 1.1 The Isles of Scilly Special Area of Conservation 5 1.2 Special Areas of Conservation 5 1.3 The Management Scheme 6 1.4 Background to the Habitats Directive and the Habitats Regulations 6 1.4.1 The Habitats Directive 6 1.4.2 The Habitats Regulations: Regulatory and Policy Framework 6 2. Aims and Objectives 8 2.1 Overall Aim 8 2.2 Objectives of the Management Scheme 8 3. Stakeholders of the Isles of Scilly Marine SAC 9 3.1 Relevant and Competent authorities 9 3.2 Non statutory Stakeholders and User groups 10 4. Relationships between existing designations 11 4.1 Area of Outstanding National Beauty (AONB) 11 4.2 Special Protected Area (SPA) 12 4.3 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) 12 4.4 Designation Relationship Summary 13 5. Reasons for Designation 15 5.1 Qualifying Features 15 5.1.1 Qualifying habitats 15 5.1.2 Qualifying species 15 5.2 Detailed description of Features of Interest, and Sub-features 15 5.3 SAC Biotopes (Biological Communities associated with substrata types) 17 6. Isles of Scilly Marine SAC Conservation Objectives 20 6.1 Introduction 20 6.2 Conservation Objectives for the Isles of Scilly Marine SAC 20 6.2.1 The Conservation Objectives 21 6.3 Favourable Condition 22 6.3.1 Monitoring for Favourable Condition 22 6.3.2 The Favourable Condition Table 22 7. -

Breeding Seabirds on the Isles of Scilly Vickie Heaney, Leigh Lock, Paul St Pierre and Andy Brown

BB August 2008 22/7/08 12:26 Page 418 Important Bird Areas: Breeding seabirds on the Isles of Scilly Vickie Heaney, Leigh Lock, Paul St Pierre and Andy Brown Razorbills Alca torda Ren Hathway ABSTRACT The Isles of Scilly are long famous for attracting rare migrant birds, and much-visited in spring and autumn by those in search of them, but it is much less widely appreciated that the islands also support an outstanding and internationally important assemblage of breeding seabirds.We document the present status and distribution of seabirds on the islands, set populations in their regional, national and international contexts, and review recent and historical changes in numbers. In the light of some alarming population trends, we discuss the possible roles of persecution, disturbance, predation, habitat change, waste and fisheries management, climate change and pollution in bringing about these changes. Finally, we identify a range of actions that we believe will do much to improve the fortunes of the seabirds breeding in the archipelago. 418 © British Birds 101 • August 2008 • 418–438 BB August 2008 22/7/08 12:26 Page 419 Breeding seabirds on the Isles of Scilly he Isles of Scilly are situated some 45 km seabird interest, it is not surprising that many of to the west of the southwest tip of the the older county avifaunas refer to the presence TBritish mainland. Five inhabited islands of seabirds in some numbers. However, few of and at least 300 smaller, uninhabited islands, the references are quantitative and information islets and rocks cover a total area of 16 km2. -

A Review of the Ornithological Interest of Sssis in England

Natural England Research Report NERR015 A review of the ornithological interest of SSSIs in England www.naturalengland.org.uk Natural England Research Report NERR015 A review of the ornithological interest of SSSIs in England Allan Drewitt, Tristan Evans and Phil Grice Natural England Published on 31 July 2008 The views in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Natural England. You may reproduce as many individual copies of this report as you like, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with Natural England, 1 East Parade, Sheffield, S1 2ET ISSN 1754-1956 © Copyright Natural England 2008 Project details This report results from research commissioned by Natural England. A summary of the findings covered by this report, as well as Natural England's views on this research, can be found within Natural England Research Information Note RIN015 – A review of bird SSSIs in England. Project manager Allan Drewitt - Ornithological Specialist Natural England Northminster House Peterborough PE1 1UA [email protected] Contractor Natural England 1 East Parade Sheffield S1 2ET Tel: 0114 241 8920 Fax: 0114 241 8921 Acknowledgments This report could not have been produced without the data collected by the many thousands of dedicated volunteer ornithologists who contribute information annually to schemes such as the Wetland Bird Survey and to their county bird recorders. We are extremely grateful to these volunteers and to the organisations responsible for collating and reporting bird population data, including the British Trust for Ornithology, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the Joint Nature Conservancy Council seabird team, the Rare Breeding Birds Panel and the Game and Wildlife Conservancy Trust. -

Ecological Assessment

ENNOR FARM ISLES OF SCILLY ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT January 2021 8128.002 Version 5.0 Document Title Ennor Farm Ecological Assessment Prepared for CampbellReith Prepared by TEP Ltd Document Ref 8128.002 Author Gemma Hassall Date October 2020 Checked Lee Greenhough Approved Lee Greenhough Amendment History Check / Modified Version Date Approved Reason(s) issue Status by by Minor update to reflect design freeze and Final for client 2.0 01/12/2020 RAR LG additional appendix approval Inclusion of CampbellReith Drainage 3.0 16/12/2020 LG RAR Strategy plan (ref 13394-CRH-XX-XX-DR-C- Final 5050-P2 Drainage Strategy) January CampbellReith update of proposed layout 4.0 - - For submission 2021 plan Amendment to reflect additional tree removal Final for 5.0 11/01/2021 RAR LG and replacement required to accommodate Planning Issue visibility splay; phase 1 map correction Ennor Farm St. Mary’s, Isles of Scilly Ecological Assessment Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 2 Site Description ....................................................................................................... 2 2.0 METHODS............................................................................................................... 4 Desktop Study ......................................................................................................... 4 Habitat -

BIC-1960.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 Obituary—Lt.-Col. B. H. Ryves ... ... ... ... 6 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 7 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 9 Arrival and Departure Tables ... ... ... ... 42 The Isles of Scilly ... ... ... ... ... 47 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Scilly ... 55 The Breeding Habits of the Corn-Bunting ... ... 57 Supplementary Notes on the Breeding Habits of the Corn- Bunting ... ... ... ... ... ... 77 Our Society and the Protection of Birds Act ... ... 86 Wildfowl Counts in Cornwall ... ... ... ... 87 Melancoose Reservoir, Newquay ... ... ... ... 88 Bird Notes from the Bishop Rock Lighthouse ... ... 89 Survey of Whinchat and Stonechat ... ... ... 95 Forest Types and Common Forest Birds in West Cornwall ... 97 The Macmillan Library ... ... ... ... ... 104 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 106 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 107 List of Members ... ... ... ... ... 108 Committees for 1960 and 1961 ... ... ... ... 122 Index 123 THIRTIETH REPORT OF The Cornwall Bird-Watching and Preservation Society 1960 Edited by J. E. BECKERLEGGE & G. ALLSOP (kindly assisted by H. M. QUICK, R. H. BLAIR & A. G. PARSONS) The Society Membership now exceeds seven hundred; during the year, forty have joined the Society, but losses by death and resigna tion were fourteen. On February 6th a meeting was held at the Museum in Truro, at which a talk on " Bird recognition in the field," by Mr. Parsons, was followed by a discussion. The twenty-ninth Annual General Meeting was held in Truro on April 23rd under the chairmanship of Dr. Blair. At this meeting Sir Edward Bolitho, Dr. Blair, Mr. Martyn, Col. Ryves, the Rev. J. E. Beckerlegge and Dr. Allsop were re-elected as President, Chair man, Treasurer and Secretaries, respectively. -

Site Improvement Plan Isles of Scilly Complex

Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 Sites (IPENS) Planning for the Future Site Improvement Plan Isles of Scilly Complex Site Improvement Plans (SIPs) have been developed for each Natura 2000 site in England as part of the Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 sites (IPENS). Natura 2000 sites is the combined term for sites designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protected Areas (SPA). This work has been financially supported by LIFE, a financial instrument of the European Community. The plan provides a high level overview of the issues (both current and predicted) affecting the condition of the Natura 2000 features on the site(s) and outlines the priority measures required to improve the condition of the features. It does not cover issues where remedial actions are already in place or ongoing management activities which are required for maintenance. The SIP consists of three parts: a Summary table, which sets out the priority Issues and Measures; a detailed Actions table, which sets out who needs to do what, when and how much it is estimated to cost; and a set of tables containing contextual information and links. Once this current programme ends, it is anticipated that Natural England and others, working with landowners and managers, will all play a role in delivering the priority measures to improve the condition of the features on these sites. The SIPs are based on Natural England's current evidence and knowledge. The SIPs are not legal documents, they are live documents that will be updated to reflect changes in our evidence/knowledge and as actions get underway. -

The Development of Onshore Wind Turbines

Renewable Energy Planning Guidance Note 3 The development of onshore wind turbines Current Document Status Version V4 Status Approved Date 17/12/13 Approving body PPAP Responsible Officer NDH Date approved 25/11/11 Version History Date Version Author/Editor Comments 25/11/11 V1 PR PPAP adopted version 17/07/12 V2 EIW Revisions 04/06/13 V3 NDH Revision relating to Historic Environment 03/02/14 V4 NDH Revisions relating to Noise; Proximity to roads/railways; fees; requirements to consult prior to submission of application and bird guidance. 0 V3 June 2013 The Development of Onshore Wind Turbines in Cornwall This guidance document has been prepared to assist all parties involved in the renewable energy development process. It is intended that the guidance document will be adopted by the Council as a “Supplementary Planning Document” following the adoption of the Council’s Core Strategy proposed after 2013. Until then the status of this document is that it has been approved by Members of the Council’s Planning Policy Advisory Panel and while it will not attract the full weight of an SPD document will attract some weight in decisions reached on planning applications. Introduction This guidance note aims to provide planning advice in respect of onshore wind. The Government has set targets to increase electricity and/or heat generation from renewable sources. Cornwall Council is keen to promote the generation of electricity and/or heat from renewable sources in Cornwall in order to contribute towards a more sustainable future. This guidance note is part of a series of planning guidance notes for Renewable Energy prepared by Cornwall Council. -

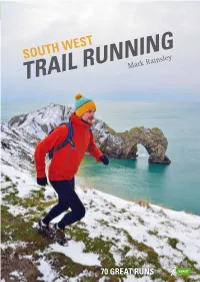

Trail Running

SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST TRAIL RUNNING Mark Rainsley 70 routes for the off-road runner: these tried and tested TRAIL RUNNING paths and tracks cover the south-west of England, including the Isles of Scilly. Trail running is a great way to explore the South West and to immerse TRAIL yourself in its incredible landscapes. This guide is intended to inspire runners of all abilities to develop the skills and confidence to seek out new trails in their local areas as well as further afield. They are all great runs; selected for their runnability, landscape and scenery. The selection is deliberately diverse and is chosen to highlight the R incredible range of trail running adventures that the South West can UNNING offer. The runs are graded to help progressive development of the skills and confidence needed to tackle more challenging routes. TRAIL RUNNING FOR EVERYONE CLOSE TO TOWN & FAR AFIELD. Mark Rainsley ISBN 9781906095673 9 781906 095673 Front cover – Durdle Door Back cover – Porthcothan Bay www.pesdapress.com 70 GREAT RUNS h g old ou essex r W 65 wood W 64 g Downs the- Stow-on- Salisbury Swindon Rin North Marlbo 59 encester 63 The Bournemouth r 62 Plain 67 Ci Cotswolds 58 Salisbury ne 53 d 61 r r 52 Cheltenham 70 Distance Ascent Route Route Distance Ascent Route Route Poole Chase 51 Page Page WILTSHIRE 57 Cranbo 55 Forum (km) (m) No. Name Chippenham (km) (m) No. Name arminster 56 Blandfo 50 W 69 5.5 100 56 The Wardour Castles 265 13 425 48 Durdle Door 231 60 49 68 7 150 70 Cleeve Hill 325 48 13 425 51 St Alban’s Head 243 54 chester -

Preliminary Ecological Appraisal & Primary Bat Roost Assessment Of

Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust Trenoweth, St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly, TR21 0NS Tel: 01720 422153 [email protected] www.ios-wildlifetrust.org.uk PRELIMINARY ECOLOGICAL APPRAISAL & PRIMARY BAT ROOST ASSESSMENT OF: BANK COTTAGE SOUTH’ARD BRYHER ISLES OF SCILLY TR23 0PR Client: Ms Mary Loweth Our reference: BS10-2018 Report Date: 13th November 2018 Author: Darren Hart BSc (Hons) Report peer reviewed: Darren Mason BSc (Hons) Report Authorised: Sarah Mason 21.11.18 REPORT ISSUED IN ELECTRONIC FORMAT ONLY Registered Charity no 1097807. Patron: His Royal highness The Prince of Wales Page 1 of 26 This page is intentionally blank Page 2 of 26 Contents Non-Technical Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.0. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Survey and reporting ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 The application site ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Details of proposed works ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The Status of Seabirds Breeding in the Isles of Scilly 2015/16

The status of seabirds breeding in the Isles of Scilly 2015/16 Vickie Heaney & Paul St Pierre April 2017 (amended April 2020)* RSPB Cornwall Office No 2, The Old Smelting House, Chyandour Coombe, Penzance, TR18 3LP [email protected] [email protected] The status of seabirds breeding in the Isles of Scilly 2015/16 Contents Page no Summary 1 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Objectives 4 2 2015/16 Isles of Scilly seabirds survey 5 2.1 Background 5 2.2 Methods 5 2.3 Results 5 3 Seabird diversity: An overview of seabirds breeding in Scilly 6 3.1 Most abundant and most widespread seabird species 6 3.2 Important breeding seabird populations 7 3.3 Changes in the seabird breeding community 7 3.4 Changes in the seabird interest features of the SSSIs 10 4 Species accounts 13 4.1 Northern fulmar 14 4.2 Manx shearwater 16 4.3 European storm petrel 18 4.4 Great cormorant 19 4.5 European shag 21 4.6 Lesser black-backed gull 23 4.7 Herring gull 25 4.8 Great black-backed gull 27 4.9 Black legged kittiwake 29 4.10 Common tern 31 4.11 Common guillemot 33 4.12 Razorbill 35 4.13 Atlantic puffin 37 5 Site accounts 39 5.1 The status of seabirds in the Isles of Scilly SPA 39 5.2 The status of seabirds in the Isles of Scilly seabird SSSIs 39 6 Discussion 41 6.1 Recent changes in seabird distribution and numbers in Scilly 41 6.1.1 The condition of the Isles of Scilly SPA 41 6.1.2 The condition of the seabird SSSIs in the Isles of Scilly 41 6.2 Factors driving change in seabird numbers in Scilly 42 6.2.1 Mammalian predators 45 6.2.2 Climate change and food availability -

Seabird Monitoring & Research Project Isles of Scilly 2016

Seabird Monitoring & Research Project Isles of Scilly 2016 GPS marking Manx shearwater burrows on St Agnes. Photo: Ed Marshall Vickie Heaney Isles of Scilly Seabird Recovery Project Officer [email protected] Summary of Results Monitoring of seabird numbers and productivity on St Agnes and Gugh • Manx shearwater o breeding population increased from 22 pairs in 2013 (pre- rat eradication) to 73 pairs in 2016 (post rat eradication) o New areas colonised around Kittern Hill and Castella Down o 32 ‘star-gazing’ chicks recorded (4 St. Agnes, 28 Gugh) • Storm petrel o recorded breeding successfully on St. Agnes & Gugh for second year o 6 storm petrel nest boxes installed in dry stone walling on St. Agnes • Only 5 pairs of kittiwakes built nests on St Agnes, no chicks hatched • Lesser black-backed gull o colony on Gugh stable at 400 pairs since 2013 o productivity on Gugh 0.51 – 0.60 chicks per pair • Two broods of ringed plover chicks observed on St. Agnes Community involvement on St Agnes and Gugh • Ten St. Agnes residents have been involved in playback surveys • 12 community members participated in shearwater ‘chick check walks’ Population monitoring work on Annet and outer islands • Islands missed in the 2015 SPA count due to bad weather o Puffin, White, Shipman, Illiswilgig, Castle Bryher and Men-a-vaur surveyed o Cormorant population count significantly increased on White Island • Annual count of breeding seabirds on Annet, numbers generally stable • Sample beach on Annet surveyed for breeding storm petrel Productivity monitoring work across the archipelago • Herring gull: Samson 0.43 chicks per pair (chpp) (n=53) & Hugh Town 1.22 chpp (n=9) • Kittiwake: Turk’s Head 5 pairs nested, no chicks fledged • Fulmar: Menawethan 0.22 chpp (n=45) & Daymark 0.19 chpp (n=57) • Common tern: Annet and Merrick Island 0.41 chpp (n=14) • Shags on Samson: 0.30 chpp (n=27) • Manx shearwater: Peninnis (n=7) & St Helen’s (n=42), little sign of burrow activity later in season Bryher, St.