The Baroque Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

INNER CHAMBERS Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Couperin • Hotteterre • Lully • Marais • Montéclair Les Ordinaires Leela Breithaupt, Traverso Erica Rubis, Viola da gamba David Walker, Theorbo Inner Chambers Inner Chambers Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Introduction préluder sur la flûte traversière (‘The Art of Preluding on Jacques-Martin Hotteterre (1674–1763): Michel Pignolet de Montéclair the Flute’). In the manual, Hotteterre teaches his pupils L’Art de préluder sur la (1667–1737): Musical life at the court of Louis XIV was highly ritualised step by step how to improvise or write a prelude in various flûte traversière (1719) Brunetes anciènes et modernes (1725) and filled with dazzling formal public displays. However, keys, and ends with two preludes composed by the 1 Prelude in D major 4:20 $ Je sens naître en mon coeur 1:56 the Sun King also enjoyed music in his more private author. As one of the king’s employed chamber spheres. This debut album reveals the intimate sound musicians, Hotteterre was well respected both as a flautist François Couperin (1668–1733): Deuxième Concert – Suite (1720) 14:59 world that Louis XIV embraced in his inner chambers at and composer. the Palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau. The music The French Suite was a very popular musical form Premier Concert (1722) 11:03 % Prélude 1:41 reflects the court’s aesthetic preferences: lavish display of which was typically comprised of several dance 2 Prélude 2:18 ^ Allemande 1:49 ornaments and affluence paired with strict hierarchies, movements including Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, 3 Allemande 1:59 & Courante à l’italienne 1:18 love of allegory, and an affected nostalgia for pastoral life Gavotte, Gigue and Menuet, among others. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Park, Chungwon Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 04:28:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194278 CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Chungwon Park ___________________________ Copyright © Chungwon Park 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College The UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Chungwon Park entitled Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments in Basso Continuo Group and Obbligato Instrumental Forces for Performance of Selected Sacred Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Thomas Cockrell Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

4 Classical Music's Coarse Caress

The End of Early Music This page intentionally left blank The End of Early Music A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century Bruce Haynes 1 2007 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2007 by Bruce Haynes Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haynes, Bruce, 1942– The end of early music: a period performer’s history of music for the 21st century / Bruce Haynes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-518987-2 1. Performance practice (Music)—History. 2. Music—Interpretation (Phrasing, dynamics, etc.)—Philosophy and aesthetics. I. Title. ML457.H38 2007 781.4′309—dc22 2006023594 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper This book is dedicated to Erato, muse of lyric and love poetry, Euterpe, muse of music, and Joni M., Honored and Honorary Doctor of broken-hearted harmony, whom I humbly invite to be its patronesses We’re captive on the carousel of time, We can’t return, we can only look behind from where we came. -

Baroque Music 1600-1750 Definition

Baroque Music 1600-1750 Definition The word “Baroque” means “a misshaped pearl”. This term was initially used to describe the flamboyant, decorative lines and curves of architecture from the 17th to mid 18th centuries (1650s- 1700s) & eventually used to describe the music of this period as well. The Baroque period was an important time in the history of the world. This era witnessed new exploration of ideas and innovations in the arts, literature and philosophy, to name a few: Sir Isaac Newton discovered the laws of gravity Galileo Galilei laid down the foundation of astronomy Sir William Harvey discovered the circulation of blood Historical overview Throughout the Baroque period, composers continued to be employed by the church and wealthy ruling class. This system of employment was called the patronage system. As the patron paid the composer for each work and usually decided what kind of piece the composer should write, this limited the composer’s creative freedom. Monarchs (Royalty) had absolute power. The nobility owned land and were entertained by hunting and music. Peasants worked hard for their bread and butter and could relax after hours. Italy was the hub of new culture and led the way. This was an age of paradox/contrast Church vs. State Monarchy vs. Bourgeoisie Aristocracy vs. Affluent Middle Class Scientific Research vs. Superstition, Witchcraft Importance of humanity vs. Religious Persecution Music responded to this paradox Vocal vs. Instrumental Church Modes vs. Tonality (Major, minor) Sacred Music vs. Secular Music Polyphonic -

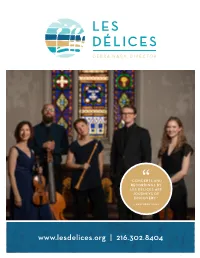

216.302.8404 “An Early Music Group with an Avant-Garde Appetite.” — the New York Times

“CONCERTS AND RECORDINGS“ BY LES DÉLICES ARE JOURNEYS OF DISCOVERY.” — NEW YORK TIMES www.lesdelices.org | 216.302.8404 “AN EARLY MUSIC GROUP WITH AN AVANT-GARDE APPETITE.” — THE NEW YORK TIMES “FOR SHEER STYLE AND TECHNIQUE, LES DÉLICES REMAINS ONE OF THE FINEST BAROQUE ENSEMBLES AROUND TODAY.” — FANFARE “THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES ARE FIRST CLASS MUSICIANS, THE ENSEMBLE Les Délices (pronounced Lay day-lease) explores the dramatic potential PLAYING IS IRREPROACHABLE, AND THE and emotional resonance of long-forgotten music. Founded by QUALITY OF THE PIECES IS THE VERY baroque oboist Debra Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established a FINEST.” reputation for their unique programs that are “thematically concise, — EARLY MUSIC AMERICA MAGAZINE richly expressive, and featuring composers few people have heard of ” (NYTimes). The group’s debut CD was named one of the "Top “DARING PROGRAMMING, PRESENTED Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009" (NPR's Harmonia), and their BOTH WITH CONVICTION AND MASTERY.” performances have been called "a beguiling experience" (Cleveland — CLEVELANDCLASSICAL.COM Plain Dealer), "astonishing" (ClevelandClassical.com), and "first class" (Early Music America Magazine). Since their sold-out New “THE CENTURIES ROLL AWAY WHEN York debut at the Frick Collection, highlights of Les Délices’ touring THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES BRING activites include Music Before 1800, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner THIS LONG-EXISTING MUSIC TO Museum, San Francisco Early Music Society, the Yale Collection of COMMUNICATIVE AND SPARKLING LIFE.” Musical Instruments, and Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Les — CLASSICAL SOURCE (UK) Délices also presents its own annual four-concert series in Cleveland art galleries and at Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights, OH, where the group is Artist in Residence. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

Martha Jane Gilreath Submi Tted As an Honors Paper in the Iartment Of

A STTJDY IN SEV CENT1 CHESTRATIO>T by Martha Jane Gilreath SubMi tted as an Honors Paper in the iartment of Jiusic Voman's College of the University of Xorth Carolina Greensboro 1959 Approved hv *tu£*l Direfctor Examining Committee AC! ' IKTS Tt would be difficult to mention all those who have in some way helped me with this thesis. To mention only a few, the following have mv sincere crratitude: Dr. Franklyn D. Parker and members of the Honors -fork Com- mittee for allowing me to pursue this study; Dr. May ". Sh, Dr. Amy Charles, Miss Dorothy Davis, Mr. Frank Starbuck, Dr. Robert Morris, and Mr, Robert Watson for reading and correcting the manuscript; the librarians at Woman's College and the Music Library of the University of North Carolina through whom I have obtained many valuable scores; Miss Joan Moser for continual kindness and help in my work at the Library of the University of North Carolina; mv family for its interest in and financial support of my project; and above all, my adviser, Miss Elizabeth Cowlinr, for her invaluable assistance and extraordinary talent for inspiring one to higher scholastic achievenent. TAm.E OF COKTB 1 1 Chapter I THfcl 51 NTURY — A BACKGROUND 3 Chapter II FIRST RUB OR( 13 Zhapter III TT*rn: fTIONS IN I] 'ION BY COMPOSERS OF THE EARLY SEVE TORY 17 Introduction of nasso Continuo 17 thods of Orchestration 18 Duplication of Instruments 24 Pro.gramatic I'ses of Scoring .25 id Alternation between Instruments. .30 Introduction of Various Instrumental devices 32 Dynamic Contrasts 32 Rowing Methods 33 Pizzicato -

CDS 4 6 17 with Wendy Week 1.Pages

Amherst Early Music Festival 2017 Central Program Classes Week I Music of England and Spain: Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque Welcome to our exciting Central Program class offerings! Grab a highlighter and take a deep breath! This catalogue includes classes for Week I for students registering for the Central Program. Here’s how to register for classes: 1. Read the catalogue carefully. Classes are listed by period of the day, then by instrument. Pay particular attention to the Classes of General Interest! 2. Select three choices for each period. Occasionally we need to cancel or shift classes, and that’s when your alternate choices are vital to us. By making three choices now, you help make the class sorting process move much more quickly than if we have to call you for your choices.* 3. To fill out a class choice form go to http://www.amherstearlymusic.org/Festival_Classes_combinedform or request a paper form by emailing [email protected]. Fill out the evaluation, giving us as much information about your skills and desires as you can. If filling out a paper form, indicate your 1st, 2nd, and 3rd class choices for each period by copying the class’s sorting codes [in square brackets after the class’s title] onto the Class Choice Form. If you are filling out the form online, you will choose classes by title in the drop- down menu. 4. If you are also attending Week II, please fill out a separate form for Week II classes, using the separate Week II Class Descriptions. If sending paper forms, mail them to us at Amherst Early Music, 35 Webster Street, Nathaniel Allen House, West Newton MA 02465. -

George Frideric Handel's University of Notre Dame Chorale & Festival

UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC PRESENTS George Frideric Handel’s MESSIAH University of Notre Dame Chorale & Festival Baroque Orchestra Alexander Blachly, Director Claire Maxa, Katie Surine, Maya Jain - soprano soloists Gabriela Solis, Gianna Van Heel – alto soloists Carlos Carenas - tenor soloist Nathan Kistler, Edward Vogel - bass soloists 8:00 p.m., Friday, December 2, 2016 8:00 p.m., Saturday, December 3, 2016 Leighton Concert Hall Marie P. DeBartolo Center for the Performing Arts - 2 - Sinfony [Overture] Comfort Ye (Isaiah 40: 1-3); Ev’ry Valley Shall Be Exalted (Isaiah 40: 4) (tenor recitative and aria – Carlos Cardenas) And the Glory of the Lord (Isaiah 51: 5) (chorus) Thus Saith the Lord (Haggai 2: 6-7; Malachi 3: 1) (baritone recitative – Nathan Kistler) But Who May Abide (Malachi 3: 2) (baritone aria – Edward Vogel) And he Shall Purify (Malachi 3: 3) (chorus) Behold, a Virgin Shall Conceive (Isaiah 7: 14); O Thou That Tellest Good Tidings (Isaiah 40: 9; 40: 1) (alto recitative and aria with chorus – Gabriela Solis) For Unto Us a Child is Born (Isaiah 9: 6) (chorus) Pifa [Pastoral Symphony] (strings and continuo) There Were Shepherds (Luke 2: 8); And, Lo, the Angel (Luke 2: 9); And the Angel Said (Luke 2: 10-11); And Suddenly (Luke 2: 13) (soprano recitatives – Claire Maxa) Glory to God (Luke 2: 14) (chorus) Rejoice Greatly (Zechariah 9:9-10) (soprano aria – Katie Surine) Then Shall the Eyes of the Blind (Isaiah 35: 5-6); He Shall Feed his Flock (Isaiah 40: 11; Matthew 11: 28-29) (alto recitative and alto/soprano -

ACMP Workshop Final

2017 Worldwide Chamber Music Workshop Guide Chamber music study and performance opportunities for adult amateur musicians www.acmp.net ACMP – ASSOCIATED CHAMBER MUSIC PLAYERS 2017 North American Rebecca Rodman International Kristina Höschlova Board of Directors Outreach Council Anacortes, WA Ambassadors CZECH REPUBLIC Council Janet White Janet White Larry Schiff Patsy Hulse Chair, ACMP Chair New York, NY Floryse Bel Bennett NEW ZEALAND San Diego, C San Diego, CA Chair Peggy Skemer SWITZERLAND Ronald Ling Anthony James Vine Patricia K. Addis Princeton, NJ SINGAPORE Vice Chair, ACMP Iowa City, IA Marcel Arditi New York, NY Peter Tacy SWITZERLAND Michel Mayoud Edwin K. Annavedder Mystic, CT FRANCE Christiana Carr Carlsbad, CA Christian Badetz Treasurer, ACMP Ivy A. Turner RUSSIA Tommaso Napoli Moraga, CA Edward J. Bridge Cambridge, MA ITALY Louisville, KY Keith Bowen Peter Hildebrandt George C. Valley ENGLAND Akira Okamoto Chair, ACMP Foundation Christina D. Carrière Los Angeles, CA JAPAN Johns Creek, GA Montréal, QC Stephan Brandel Joan E. Vazakas CHINA Bettina Palaschewski David Pearl Steven Flanders Bonita Springs, FL BELGIUM Treasurer, Pelham, NY Laurent Cabanel ACMP Foundation Margaret K. Walker FRANCE Mihai Perciun Washington, DC Randy Graham Bloomfield, CT ROMANIA Gresham, OR Jean Carol Harriet Wetstone Lucia Norton Woodruff SWITZERLAND Maja Popova Secretary, ACMP; Leon J. Hoffman Austin, TX MONTENEGRO ACMP Foundation Chicago, IL Phoebe Csenky Lenox, MA David Yang SCOTLAND Markus Prenneis William T. Horne Philadelphia, PA GERMANY Floryse Bel Bennett Mill Valley, CA Aldo De Vero Tolochenaz, Switzerland ITALY Martina Rummel Cynthia L. Howk GERMANY Beatrice Francais Rochester, NY Martin Donner New York, NY AUSTRIA Marjana Rutkowski Martha Ann Jaffe Joel Epstein BRAZIL Laura Jean Goldberg Newton Center, MA ISRAEL New York, NY Christel & Bernhard Janis Krauss Stéphane Fauth Schluender Karl Roth North Augusta, SC FRANCE PORTUGAL Westerville, OH Adwyn Lim Harald Gabbe Takaharu Shimura Gwendoline A. -

Baroque Music Webquest Name

Baroque Music WebQuest Name: History Historians have assigned certain dates to musical “eras.” These dates however are not exact. You could imagine that if one type of music was very popular today that it would be impossible for ALL interest to stop on one single day. What does Baroque mean? How does it define this period of music? Info Source: What musical era preceded the Baroque era? Dates? Info Source: List two unique characteristics for each of these time periods? Info Source(s): Period 1 c i t s i r e t c a r a h C 1 c i t s i r e t c a r a h C Was this music called Baroque when it was being composed? Info Source: Instruments People have always used different types of instruments to play music. The first instruments ever were objects that cavemen found in the wild! Over time, civilization advanced and technology led to new instruments. Using the links page, find information about 2 Baroque instruments. Describe: What they were made of? How they sounded? How they worked? Did their design reflect this time period? Instrument 1 Instrument 2 Include a picture of the instrument and a few important facts in your PowerPoint presentation. Forms Define at least 4 of the following Baroque musical forms: Fugue Fantasia Sonata Suite Passacaglia Canzona Concerto Aria Composers Groves is publishing a new edition of their music encyclopedia and they need YOU! Research one of the following composers. Write about your composer by creating an encyclopedia entry: concise and brief.