Music History I Course Under the Supervision of Professors Patricia Callaway and Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

INNER CHAMBERS Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Couperin • Hotteterre • Lully • Marais • Montéclair Les Ordinaires Leela Breithaupt, Traverso Erica Rubis, Viola da gamba David Walker, Theorbo Inner Chambers Inner Chambers Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Royal Court Music of Louis XIV Introduction préluder sur la flûte traversière (‘The Art of Preluding on Jacques-Martin Hotteterre (1674–1763): Michel Pignolet de Montéclair the Flute’). In the manual, Hotteterre teaches his pupils L’Art de préluder sur la (1667–1737): Musical life at the court of Louis XIV was highly ritualised step by step how to improvise or write a prelude in various flûte traversière (1719) Brunetes anciènes et modernes (1725) and filled with dazzling formal public displays. However, keys, and ends with two preludes composed by the 1 Prelude in D major 4:20 $ Je sens naître en mon coeur 1:56 the Sun King also enjoyed music in his more private author. As one of the king’s employed chamber spheres. This debut album reveals the intimate sound musicians, Hotteterre was well respected both as a flautist François Couperin (1668–1733): Deuxième Concert – Suite (1720) 14:59 world that Louis XIV embraced in his inner chambers at and composer. the Palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau. The music The French Suite was a very popular musical form Premier Concert (1722) 11:03 % Prélude 1:41 reflects the court’s aesthetic preferences: lavish display of which was typically comprised of several dance 2 Prélude 2:18 ^ Allemande 1:49 ornaments and affluence paired with strict hierarchies, movements including Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, 3 Allemande 1:59 & Courante à l’italienne 1:18 love of allegory, and an affected nostalgia for pastoral life Gavotte, Gigue and Menuet, among others. -

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759)

Hey Kids, Meet George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759) George Frideric Handel was born on February 23, 1685 in the North German province of Saxony, in the same year as Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. George's father wanted him to be a lawyer, though music had captivated his attention. His mother, in contrast, supported his interest in music, and he was allowed to take keyboard and music composition lessons. His aunt gave him a harpsichord for his seventh birthday which Handel played whenever he had the chance. In 1702 Handel followed his father's wishes and began his study of law at the University of Halle. After his father's death in the following year, he returned to music and accepted a position as the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In the next year he moved to Hamburg and accepted a position as a violinist and harpsichordist at the opera house. It was there that Handel's first operas were written and produced. In 1710, Handel accepted the position of Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who was soon to be King George I of Great Britain. In 1712 he settled in England where Queen Anne gave him a yearly income. In the summer of 1717, Handel premiered one of his greatest works, Water Music, in a concert on the River Thames. The concert was performed by 50 musicians playing from a barge positioned closely to the royal barge from which the King listened. It was said that King George I enjoyed it so much that he requested the musicians to play the suite three times during the trip! By 1740, Handel completed his most memorable work - the Messiah. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

NEWSLETTER American Musical Instrument Society

NEWSLETTER Of The American Musical Instrument Society Vol. XVIII, No.1 February 1989 Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art AM IS members attending the annual meeting in New York City will be able to view this exhibition of recently-acquired Korean instruments in the Andre' Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments. sions, musical interludes, and other activities struments, will be on view in the Amsterdam AMIS MEETS MAY 25-28 follow on the next two days, with the AMIS Gallery of the Library & Museum of the Per IN NEW YORK CITY business meeting and extra events on Sunday. forming Arts at Lincoln Center, and the The schedule (see pp. 2-3 of this Newsletter) American Museum of Natural History has In honor of the centennial of the Crosby allows ample time to visit the Andre Mertens deployed many of its non-Western instruments Brown Collection at The Metropolitan Museum Galleries for Musical Instruments at the in new galleries. of Art, the 18th-annual AMIS meeting will be Metropolitan Museum and to enjoy A Musical Other highlights of the meeting include a held in New York City, May 25-28, 1989. Most Offering, a special, NEA-funded exhibition of concert by the Mozartean Players, during of the official sessions will occur at Barnard about 100 outstanding recent acquisitions, which the Curt Sachs Award for 1989 will be College, which marks its centenary at the same many of which have not been displayed before. prllsented; this program will be followed by a time. Low-cost lodging is available in Bar The Museum is also planning a display of ex reception at the lovely townhouse of AMIS nard's dormitory, located directly across the citing new instruments by Ben Hume, a young member, Frederick R. -

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

Bach2000.Pdf

Teldec | Bach 2000 | home http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/home.html 1 of 1 2000.01.02. 10:59 Teldec | Bach 2000 | An Introduction http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/introd.html A Note on the Edition TELDEC will be the first record company to release the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach in a uniformly packaged edition 153 CDs. BACH 2000 will be launched at the Salzburg Festival on 28 July 1999 and be available from the very beginning of celebrations to mark the 250th anniversary of the composer's death in 1750. The title BACH 2000 is a protected trademark. The artists taking part in BACH 2000 include: Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt, Concentus musicus Wien, Ton Koopman, Il Giardino Armonico, Andreas Staier, Michele Barchi, Luca Pianca, Werner Ehrhardt, Bob van Asperen, Arnold Schoenberg Chor, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Tragicomedia, Thomas Zehetmair, Glen Wilson, Christoph Prégardien, Klaus Mertens, Barbara Bonney, Thomas Hampson, Herbert Tachezi, Frans Brüggen and many others ... BACH 2000 - A Summary Teldec's BACH 2000 Edition, 153 CDs in 12 volumes comprising Bach's complete works performed by world renowned Bach interpreters on period instruments, constitutes one of the most ambitious projects in recording history. BACH 2000 represents the culmination of a process that began four decades ago in 1958 with the creation of the DAS ALTE WERK label. After initially triggering an impassioned controversy, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's belief that "Early music is a foreign language which must be learned by musicians and listeners alike" has found widespread acceptance. He and his colleagues searched for original instruments to throw new light on composers and their works and significantly influenced the history of music interpretation in the second half of this century. -

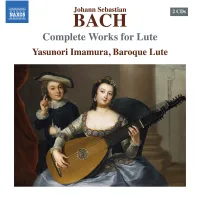

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

The Baroque Period

Developing wider KS4/5 listening: the Baroque period Simon Rushby is a freelance Simon Rushby musician, writer and education consultant, and was a director of music and senior leader in Introduction secondary schools for more than This is the first in a series of resources to help students develop their understanding and experience of 25 years. He is author of a number music from the Baroque, Classical and Romantic periods, and from the 20th and 21st centuries. of books and resources, including Starting with this one on the Baroque period, each resource will examine the style and characteristics the ABRSM’s new Discovering of the music of its time through listening and practical activities. As students prepare for and navigate Music Theory series and GCSE through their GCSE or A level courses, it’s essential that they gain a broad overview of the context and books for Rhinegold. He is an style of their set works so that they can approach wider listening questions – which expect them to ABRSM examiner, and a songwriter, have experienced a broader range of music – with confidence and understanding. composer and performer. Additionally, I hope that students will enjoy developing their ‘stylistic ear’ through listening to a range of music that they might not otherwise encounter. A general understanding of what makes Baroque music different to Classical, or Classical different to Romantic, will take them a long way, not only in their GCSE or A level studies, but also in their general cultural knowledge. This resource could be equally valuable to Year 8 or 9 students thinking of doing music for GCSE, and those learning instruments or singing who would like to develop a better understanding of the music they’re performing and, perhaps, prepare for those ‘style and period’ questions in practical exam aural tests. -

Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Park, Chungwon Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 04:28:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194278 CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Chungwon Park ___________________________ Copyright © Chungwon Park 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College The UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Chungwon Park entitled Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments in Basso Continuo Group and Obbligato Instrumental Forces for Performance of Selected Sacred Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Thomas Cockrell Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Let the Heavens Rejoice!

April 27, 2018 April 28, 2018 April 29, 2018 St. Noel Church Lakewood Congregational Church Plymouth Church UCC LET THE HEAVENS REJOICE! Concert de Simphonies (1730) – Jacques Aubert (1689–1753) Ouverture – Menuets – Gigues Sarabande – Tambourins – Chaconne In convertendo – Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Récit: In convertendo (Owen McIntosh) Choeur: Tunc repletum est gaudio Duo: Magnificavit Dominus (Elena Mullins, Jeffrey Strauss) Récit: Converte Domine captivitatem nostram (Strauss) Choeur dialogué: Laudate nomen Dei (Sarah Coffman) Trio: Qui seminant in lacrimis (McIntosh, Mullins, Strauss) Choeur: Euntes ibant et flebant INTERMISSION Conserva me (1756) – Louis-Antoine Lefebvre (1700–1763) Owen McIntosh, tenor Salve Regina à trois choeurs and basse continue – Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704) Quire Cleveland Venite exultemus (1743) – Jean-Joseph Cassanea de Mondonville (1711–1772) Récit et choeur: Venite exultemus (Mullins, Coffman) Récit: Quoniam Deus Magnus Dominus (Strauss) Récit: Quoniam ipsius est mare (Strauss) Récit: Venite adoremus (Mullins) Récit: Quia ipse est Dominus (Mullins) Récit et choeur: Hodie si vocem (Coffman) Récit: Sicut in exacerbatione (McIntosh) Récit: Quadraginta annis proximus fui (McIntosh) Duo et choeur: Gloria patri (Coffman, Mullins) Quire Cleveland (Ross Duffin, Artistic Director) Les Délices (Debra Nagy, Artistic Director) Scott Metcalfe, Guest Conductor Heartfelt thanks to Charlotte & Jack Newman and Donald W. Morrison for their generous sponsorship of this program. 2017/2018 SEASON anniversaries HELP YOUR and FAVORITE ARTS farewells ORGANIZATION Martin Kessler MUSIC DIRECTOR AS A VOLUNTEER! OPPORTUNITIES INCLUDE: Event Support MAESTRO’S FINAL CONCERT October 15th May 14th at 8pm December 10th Artist Host February 4th Maltz Performing Arts Center at the Temple-Tifereth Israel March 18th Sponsored By Case Western Ambassador Reserve Department of Music Admin. -

Johann Sebastian Bach As Lutheran Theologian

Volume 68:3/4 July/October 2004 Table of Contents The Trinity in the Bible ............................................................195 Robert W. Jenson Should a Layman Discharge the Duties of the Holy Ministry? ...................................................................................... 207 William C. Weinrich Center and Periphery in Lutheran Ecclesiology................... 231 Charles J. Evanson Martin Chemih's Use of the Church Fathers in His Locus on Justification................................................................................. 271 Carl C. Beckwith Syncretism in the Theology of Georg Calixt, Abraham Calov and Johannes Musaus ................................................................ 291 Benjamin T. G. Mayes Johann Sebastian Bach as Lutheran Theologian .................. 319 David P. Scaer Theological Observer ................................................................ 341 Toward a More Accessible CTQ Delay of Infant Baptism in the Roman Catholic Church Book Reviews .......................................................................... 347 Baptism in the Reformed Tradition: an Historical and Practical Theology. By John W. Riggs ..................................................... David P. Scaer The Theology of the Cross for the Zlst Century: Signposts for a Multicultural Witness. Edited by Albert L. Garcia and A.R. Victor Raj....................................................................... ohT. Pless The Arts and Cultural Heritage of Martin Luther. Edited by Nils Holger Peterson et