Medicine and Nuclear War: Preventing Proliferation and Achieving Abolition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE NATIONAL FORUM the National CFIDS Foundation

THE NATIONAL FORUM The National CFIDS Foundation Vol. 27, No. 1 – Summer 2021 NCF ANNOUNCES NEW GRANT RECIPIENT By Alan Cocchetto, NCF Medical Director April 22, 2021 – Copyright 2021 The National CFIDS Foundation is pleased to announce their latest research grant recipient, Dr. Jack Wands. Dr. Wands is a Professor of Gastroenterology and Medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Wands' proposal which is titled, “Aspartate asparaginyl beta- hydroxylase (ASPH) as an etiologic factor in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS)” has received $65,000 from the National CFIDS Foundation. Dr. Wands has over 600 peer-reviewed medical journal articles in publication. According to the Foundation, there is evidence that ASPH may be accumulating in the cells of CFS patients. As such, this can dramatically impact the body's response to oxidative stress and hypoxia. Wands has planned both in-vitro as well as in-vivo studies in an attempt to understand the upregulation of ASPH on cell migration and signaling through various cellular pathways following exposure to an oxidative injury. Wands will also be comparing CFS patient samples with those of hepatic cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue. In addition, Wands has evidence that ASPH overexpression may be a risk factor for the early development of cancer which may be associated with CFS before the disease becomes clinically apparent or in other words, CFS as a pre-malignancy. Wands has observed this in pancreatic cancer patients. This is of importance since the National Cancer Institute has previously reported that CFS has been associated with increases in pancreatic cancer. -

The Nuclear Freeze Campaign and the Role of Organizers

Week Three Reading Guide: The Nuclear Freeze campaign and the role of organizers The reading by Redekop has been replaced by a book review by Randall Forsberg, and the long rough- cut video interview of Forsberg has been replaced by a shorter, more focused one. We start the first day with a brief discussion of Gusterson’s second article, building on the previous long discussion of the first one. September 23, 2019 Gusterson, H. 1999, “Feminist Militarism,” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 22.2, 17; https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.1999.22.2.17 This article focuses on the feminist themes Gusterson touched on in his earlier one. He begins restating the essentialist position and its opposition by feminists via “social constructedness.” Second-wave feminism started with Simone de Beauvoir’s idea that gender is constructed (“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”) and extending to post-structuralist Judith Butler, for whom gender is a performance, potentially fluid, learned and practiced daily based on cultural norms and discourses. Gusterson is intrigued by the idea of feminist militarism as performance. “If we weren’t feminists when we went in [to the military], we were when we came out.” What was meant by this? How does the military culture described in the article reflect gender essentialism? On p. 22, Gusterson argues that the women’s movement and the peace movement “remake their mythic narratives… through the tropes of revitalization.” What does he mean by this? Do you agree or disagree? Why? Is feminist militarism feminist? Does your answer depend on whether you adopt essentialist or constructivist reasoning? Wittner, L. -

Proquest Dissertations

'RANDOM MURDER BY TECHNOLOGY': THE ROLE OF SCIENTIFIC AND BIOMEDICAL EXPERTS IN THE ANTI-NUCLEAR MOVEMENT, 1969 - 1992 LISA A. RUMIEL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54104-3 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-54104-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

ZERO VOLUME 25 for the Human Race

2 0 1 4 ANNUAL REPORT NUCLEAR ZERO VOLUME 25 for the human race. not the arms race. NUCLEAR AGE HUMANIZE NOT MODERNIZE A Message from the President In the Nuclear Age, our technological capacity for destruction has outpaced our spiritual and moral capacity to control these destructive technologies. The Foundation is a voice for those committed to exercising conscience and choosing a decent future for all humanity. Wake Up!, a collection of peace poetry, can be ordered online at the NAPF Peace There is no way to humanize weapons that are Store at wagingpeace.org/shop/. inhumane, immoral and illegal. These weapons must be abolished, not modernized. And yet, all nine nuclear-armed countries are engaged in modernizing their nuclear arsenals. The US is leading the way, planning to spend more than $1 trillion on upgrading STAFF Paul K. Chappell, Peace Leadership Director its nuclear arsenal over the next three decades. Jo Ann Deck, Peace Leadership Assistant Sandy Jones, Director of Communications David Krieger, President In doing so, it is making the world more dangerous and less secure. Debra Roets, Director of Development The US could lead in humanizing rather than modernizing by Sharon Rossol, Office Manager reallocating its vast resources to feeding the hungry, sheltering the Judy Trejos, Development Officer Carol Warner, Assistant to the President homeless, providing safe drinking water, educating the poor, as well Rick Wayman, Director of Programs & as cleaning up the environment, shifting to renewable energy sources Operations and repairing deteriorating infrastructure. REPRESENTATIVES Ruben Arvizu, Latin American Representative Join us in making the shift from modernizing nuclear arsenals to Christian N. -

Everything You Treasure-For a World Free from Nuclear

Everything You Treasure— For a World Free From Nuclear Weapons What do we treasure? This exhibition is designed to provide a forum for dialogue, a place where people can learn together, exchange views and share ideas and experiences in the quest for a better world. We invite you to bring this “passport to the future” with you as you walk through the exhibition. Please use it to write notes about what you treasure, what you feel and what actions you plan to take in and for the future. Soka Gakkai International © Fadil Aziz/Alcibbum Photography/Corbis Aziz/Alcibbum © Fadil Photo credit: Photo How do we protect the things we treasure? The world is a single system The desire to protect the things and connected over space and time. In people we love from harm is a primal recent decades, the reality of that human impulse. For thousands of interdependence—the degree to years, this has driven us to build which we influence, impact and homes, weave clothing, plant and require each other—has become harvest crops... increasingly apparent. Likewise, the This same desire—to protect those choices and actions of the present we value and love from other generation will impact people and people—has also motivated the the planet far into the future. development of war-fighting As we become more aware of our technologies. Over the course of interdependence, we see that centuries, the destructive capability benefiting others means benefiting of weapons continued to escalate ourselves, and that harming others until it culminated, in 1945, in the means harming ourselves. -

PNHP Newsletter Spring 2007

PNHP Newsletter Spring 2007 Public Supports National Health Insurance 2008 Presidential Candidates' Health Plans New York Times/CBS News poll “Clinton asked at one point for a show of hands from the audience, 64 percent of Americans think that "the federal government should asking them to declare whether they preferred an employer-based system guarantee health insurance for all Americans," and 76 percent believe of insurance, a system that mandates all individuals to purchase insur- that universal access to health care is more important than recent tax ance, with help from the government if necessary, or one modeled on the cuts, according to a poll by the New York Times/CBS News in Medicare system. Overwhelmingly the audience favored moving toward February. The survey also found that 60 percent of those polled are a Medicare-like system for all Americans.” - Washington Post "willing to pay higher taxes so that all Americans have health insur- ance that they can't lose no matter what." Public support for compre- In a recent debate in Las Vegas, Sen. Hillary Clinton attacked the hensive health reform is at its highest level in over a decade. More than private health insurance industry, but failed to say if she would heed one-third of Americans (36 percent) say that the US health system the advice given by Iowa voters (above). Rep. Dennis Kucinich needs "complete rebuilding," more than at any time since 1994; 54 per- endorsed single payer national health insurance. Sen. Barack Obama cent say the system needs "fundamental" changes. Only 8 percent of lacks his own plan, but praised Former Senator John Edward’s those polled believe that the US health system needs only "minor" flawed "pay or play" approach, which attempts to shore up the disin- changes (New York Times/CBS poll February, 2007). -

Eleanor M. Kleinhans Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2v19r3zh No online items Register of the Eleanor M. Kleinhans collection Loralee Sepsey Hoover Institution Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Eleanor M. 80021 1 Kleinhans collection Title: Eleanor M. Kleinhans collection Date (inclusive): 1958-1992 Collection Number: 80021 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 17 manuscript boxes(6.8 Linear Feet) Abstract: Serial issues, correspondence, pamphlets, reports, flyers, serial issues, and other printed matter relating to various peace movements and activist causes throughout the United States, such as disarmament, draft opposition, nuclear energy opposition, foreign policy reform, and opposition to wars in Central America and Southeast Asia. Hoover Institution Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Eleanor M. Kleinhans collection, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1980. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's -

Maine Alumni Magazine, Volume 89, Number 2, Summer 2008

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines - All University of Maine Alumni Magazines Summer 2008 Maine Alumni Magazine, Volume 89, Number 2, Summer 2008 University of Maine Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines - All by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Summer 2008 A Life of Conscience and Commitment Nobel Laureate Bernard Lown ’42 visits campus Tapping the Tides Maine research study the potential for tidal power The Soldier/Scholar Remembering Sergeant Nicholas Robertson ’03 I am the Foundation “The University of Maine was the launching pad for Clark and me. I continue to care deeply about the University and want to do my part to help the next generation succeed. ” — Laurie Liscomb ’61 aurieL Liscomb graduated from the University of Maine in 1961 with a degree in Home Economics. It was at the University that Laurie met her husband Clark, class of I960. When Clark passed away in 2003, Laurie established the Clark Noyes Liscomb ’60 Prize in the University of Maine Foundation as a means of encouraging and aiding promising students enrolled in the School of Business to pursue their dreams of a career in international commerce. If you would like to learn more about establishing a scholarship, please call the University of Maine Foundation Planned Giving Staff or visit our website for more information. -

And International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW)

FESTSCHRIFT IN HONOR OF DR. VICTOR SIDEL The origins of Physicians for Social Responsibil- ity (PSR) and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) Sidney Alexander, MD Abstract Sidel 26 years later, on December 1985, with Jack This article reviews the beginnings and history of Geiger and me in Oslo, when IPPNW won the No- the physicians’ antinuclear movement. The role of bel Prize—a culmination of years of effort by many Victor W. Sidel, MD, is described, particularly his dedicated physicians and others. involvement with Physicians for Social Responsibil- Nuclear issues were then becoming a grave con- ity (PSR) and International Physicians for the Pre- cern to many. But American medicine paid little vention of Nuclear War (IPPNW). attention. “Nuclear issues are political issues.” • • • “Doctors should not become involved.” “These are I am honored and delighted to be part of this matters best left to ‘experts.’” Two years later, PSR wonderful celebration. My tasks today are to de- changed this and initiated the physicians’ anti- scribe the origins of Physicians for Social Responsi- nuclear movement. It is a story worth telling. bility (PSR) and briefly International Physicians for Figure 3 shows a timeline of historical events. the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), to review On August 3, 1939, Albert Einstein sent a letter the political climate and events of the mid 20th cen- to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt saying, tury that led to their formation, and, importantly, to Some recent work ... leads me to expect that the discuss Dr. Sidel’s role in their formation. element uranium may be turned into a new and Vic Sidel and I go back a long way. -

No More Nuclear Excuses for War!

August 6 & 9, 2005 Livermore Nuclear Weapons Lab SEEDS OF CHANGE NO NUKES! NO WARS! WHY DEMAND NUCLEAR ABOLITION NOW? In the midst of the ongoing slaughter in Iraq, why focus on a call for nuclear abolition? “America must not ignore the threats gathering against us. Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof – the smoking gun – that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.” - President Bush outlines Iraqi Threat, 10/7/02 BUT No “Weapons of Mass Destruction” (Nuclear, Biological or Chemical) were found in Iraq. Did you know? • The current U.S. nuclear stockpile is estimated at 10,350 warheads. • Approximately 5,300 are operational with another 5,000 in reserve. • 480 operational U.S. bombs are deployed at eight bases in six NATO countries, for delivery by U.S. and NATO bombers. U.S. Nuclear Excuses for War • Following the 9-11 attacks, the Bush Administration openly declared the potential first use of nuclear weapons – even against those countries that don’t have them. • The Bush Administration’s January 2002 Nuclear Posture Review plans for the first use of nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear attacks or threats involving biological or chemical weapons or “surprising military developments,” and targets countries including Iran, North Korea and Syria. Did you know? • In the run up to the U.S. attack, a “Theater Nuclear Planning Document” was drawn up for Iraq. • During the 1990s, the U.S. threatened to use nuclear weapons against Iraq, North Korea, and Libya. Did you know? • By equating chemical and biological weapons with nuclear weapons, the U.S. -

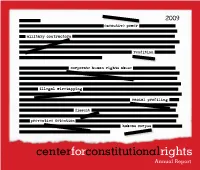

CCR Annual Report 2009

Annual Report Our Mission The Center for Constitutional Rights is a non-profit legal and educational organization dedicated to advancing and protecting the rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Founded in 1966 by attorneys who represented civil rights movements in the South, CCR is committed to the creative use of law as a positive force for social change. CCR Annual Report 2009 Letter from the Executive Director 2 Letter from the President 4 International Human Rights 6 Military Contractors in Iraq 8 Guantánamo Global Justice Initiative 10 Racial, Gender and Economic Justice 12 Accountability for Torture 16 Rendition and Ghost Detentions 18 Government Abuse of Power 20 Attacks on Dissent 22 Letter from the Legal Director 24 CCR Case Index 25 The Case for Prosecutions 32 Internships and Fellowships 34 In the News 35 100 Days Campaign 36 Get Involved 37 2009 President’s Reception 38 Friends and Allies 39 CCR Donors 44 Board of Directors and Staff 60 Financial Report 62 In Memoriam 63 Letter from the Executive Director n November 2008, we witnessed an we see a pronounced chasm between the values extraordinary and historic event in the election Obama extolled on the campaign trail and the of Barack Hussein Obama. This year also saw policies that he is putting into place as president. I Sonia Sotomayor join the Supreme Court, the And CCR has called him out on it. We launched first Latina and only the third woman to sit on our 100 Days Campaign to help focus the national that bench. -

International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War Pg

International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War pg. 1 of 6 International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War 1985 “IPPNW is committed to ending war and advancing understanding of the causes of armed conflict from a public health perspective.” Background Information “The bell of Hiroshima rings in our hearts not as a funeral knell but as an alarm bell calling out to actions to protect life on our planet.” These words came early in the Acceptance Speech of Dr. Yevgeny Chazov, speaking on behalf of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), on the occasion of the organization’s reception of the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize. Dr. Chazov’s words convey not only the urgency of responding to a critical historical event but the inspiration for the ongoing advocacy of a world free from nuclear weaponry. Yevgeny Chazov, noted cardiologist and member of the U.S.S.R. (now Russian) Cardiological Center was a co-founder of IPPNW, in 1980, along with Dr. Bernard Lown, a famed cardiologist with the Harvard School of Public Health. From its formation, IPPNW has bridged political and ideological divides, dramatically increasing its membership to 145,000 physicians by 1985. The inception of the organization took place at a time when the Cold War had the world split into two armed camps, each controlling thousands of nuclear warheads and each trying to restrain the other with threats of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD). An exchange of letters between Drs. Chazov and Lown in which they shared common concerns, led to a meeting in Geneva in 1980 which included two additional physicians from the U.S.S.R and two from the U.S.