The (Re)Shaping of South Park's Humor Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Program Guide

4/23/2021 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_SHAKE_Guide?psStartDate=09-May-21&psEndDate=15-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 09th May 2021 06:00 am Totally Wild CC C Get inspired by all-access stories from the wild side of life! 06:30 am Top Wing (Rpt) G Rod's Beary Brave Save / Race Through Danger Canyon Rod proves that he is a rooster (and not a chicken) as he finds a cub named Baby Bear lost in the Haunted Cave. A jet-flying bat roars into Danger Canyon to show off his prowess. 07:00 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G Treasure Track Blaze, AJ, and Gabby join Pegwheel the Pirate-Truck for an island treasure hunt! Following their treasure map, the friends search jungle beaches and mountains to find where X marks the spot. 07:30 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Pups Save The Runaway Turtles / Pups Save The Shivering Sheep Daring Danny X accidently drives off with turtle eggs that Cap'n Turbot had hoped to photograph while hatching. Farmer Al's sheep-shearing machine malfunctions and all his sheep run away. 07:56 am Shake Takes 08:00 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Sea Patrol: Pups Save A Frozen Flounder / Pups Save A Narwhal Cap'n Turbot's boat gets frozen in the Arctic Ice. The pups use the Sea Patroller to help guide a lost narwhal back home. 08:30 am The Loud House (Rpt) G Lincoln Loud: Girl Guru / Come Sale Away For a class assignment Lincoln and Clyde must start a business. -

Organic Press Newlsetter Fall 2019

The Organic Press The Newsletter of the Volume 19* Issue 4 Hendersonville Community Co-op Fall 2019 • Annual Harvest Celebration • Time to Vote for the Board of Directors • Farms & Foods of the Future 2 www.hendersonville.coop Organic Press Summer 2019 Table of Contents GM Musings 3 Damian Tody Editor: Gretchen Schott Cummins Board’s Eye View 4 Contributing Writers: Gretchen Schott Cummins, 2019 Annual Harvest Celebration Arrion Kitchen, Marisa Cohn, Robert Jones, Natalie Broadway, Laura Miklowitz, Damian Tody, Josh Musselwhite, MC Gaylord, Susan O’Brien, Steve Department News 6 Breckheimer We are the Hendersonville Community Co-op, a member- Board Candidates owned natural and organic food market and deli. We have been serving Hendersonville and the surrounding 10 community since 1978 when 15 families joined together to purchase quality food at better prices. We offer the best Farms and Foods of the Future in certified organic produce, groceries, herbs, bulk foods, Co+op Stronger Together 15 vitamins and supplements, cruelty-free beauty aids, wine and beer, and items for special dietary needs. The Deli offers a delicious variety of fresh soups, salads & more. Staff Picks 16 The co-op is open to the public and ownership is not required to make purchases. Everyone can shop and anyone can join. Calendar 17 Opinions expressed in The Organic Press are strictly those of the writers and do not necessarily represent an endorsement of any product or service by the News & Views from Outreach Hendersonville Community Co-op, board, management Gretchen Schott Cummins 18 or staff, unless specifically identified as such. The same is true for advertisers. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

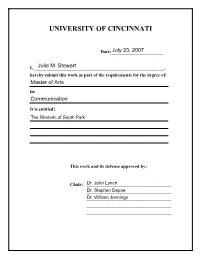

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

Senator Hee Says UHM's Strategic Plan Has Room for Improvement

Inside Features 2,7 Sports 3 Thursday Editorials 4, 5 February 23, 2006 Comics 6 Surf 8 VOL. 100 | ISSUE 105 Serving the students of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa since 1922 WWW.KALEO.ORG ‘Date Movie’ Use the right is a gross board for the waste of time right conditions Features | Page 2 Surf | Page 8 Senator Hee says UHM’s Strategic SoJ plays Campus Center Plan has room for improvement By Alana Folen many different and complex arrays Konan told the committee that Ka Leo Contributing Writer of units that we have under our the university is on schedule with campus,” Konan said. “We have the time line put forth by the criti- At a recent informational brief- a very complicated university. We cal financial audit report of UHM ing, Sen. Clayton Hee, chair of the have many units. We are serving given to the legislature in Dec. Committee on Higher Education, many different functions, and to 2005 by the state auditor. In the criticized the University of Hawai‘i me there’s a great value in trying past year, Konan said the budget at Manoa’s Strategic Plan, saying to bring some simplicity to that. level summary has been reconfig- it was too brief and “needs to be And this plan has served a really ured to show data at the unit level, beefed up.” useful function – when I go to quarterly financial reports have “When you review the plan, meetings people do quote from the been posted on the Web to enhance it’s very broad,” Hee told UHM plan and there are parts of the plan the transparency of operations, interim Chancellor Denise Konan that really help to guide and moti- and a Campus Planning Day was and UH system-wide Chief vate members of my community.” hosted in October with 250 cam- Financial Officer Howard Todo. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Med Pay/Pip Subrogation in All 50 States

MATTHIESEN, WICKERT & LEHRER, S.C. Hartford, WI ❖ New Orleans, LA ❖ Orange County, CA ❖ Austin, TX ❖ Jacksonville, FL Phone: (800) 637-9176 [email protected] www.mwl-law.com MED PAY/PIP SUBROGATION IN ALL 50 STATES From 1971 to 1976, in an effort to hold down the cost of automobile insurance, 16 states enacted no-fault automobile insurance laws which featured two key components: (1) the compulsory purchase of first-party no-fault coverage for medical benefits and loss of income for drivers and passengers (usually referred to as Personal Injury Protection or PIP benefits); and (2) limited third-party tort liability of negligent drivers. Three other states enacted similar no-fault laws during this time period, without limiting tort liability. Instead of “Med Pay” or “PIP”, some states use other terms, such as “Basic Reparation Benefits”, but the concept is the same. The no-fault experiment has received mixed reviews over the past 30 years. There have been no states since 1976 who have adopted no-fault and several states have completely repealed their no-fault laws. Advocates of no-fault argue that it reduces litigation costs and payment for non-economic (pain and suffering, etc.) damages, and provides faster payment for losses. Opponents argue that no-fault unfairly benefits negligent drivers and point to statistics which show that rather than decreasing insurance premiums, it increases premiums. While PIP benefits are usually associated with “no-fault” automobile insurance, Med Pay benefits usually are not. Although subrogation of these two types of auto insurance benefits has become big business, there is still significant misunderstanding and confusion as to these two types of benefits, and when and under what circumstances they can be subrogated. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

A Million Little Maybes: the James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover Or Jacket As Commercial Speech

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 17 Volume XVII Number 1 Volume XVII Book 1 Article 5 2006 A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. Katze Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Samantha J. Katze, A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech, 17 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 207 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Professor Susan Block-Liebe for helping the author formulate this Note and the IPLJ staff for its assistance in the editing process. This note is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 KATZE_FORMATTED_102606.DOC 11/1/2006 12:06 PM A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

Karaoke by Keysdan Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird'

Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Addicted To Spuds 'Weird' Al Yankovic Alimony 'Weird' Al Yankovic Amish Paradise 'Weird' Al Yankovic Another Rides The Bus 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Eat It 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ebay 'Weird' Al Yankovic Fat 'Weird' Al Yankovic Grapefruit Diet 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Lost On Jeopardy 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Love Rocky Road 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Want A New Duck 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic My Bologna 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Phony Calls 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ricky 'Weird' Al Yankovic Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic She Drives Like Crazy 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Spam 'Weird' Al Yankovic The Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic Yoda 'Weird' Al Yankovic You Don't Love Me Anymore 2 Live Crew Me So Horny Adam Sandler At A Medium Pace (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Adam Sandler Ode To My Car (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Piece Of S--t Car Adam Sandler What The H--- Happened To Me Adam Sandler What The Hell Happened To Me www.KeysDAN.com 501.470.6386 Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Bill Clinton Parody Bimbo No.5 Britney Spears Parody Oops I Farted Again CLEDUS T JUDD MY CELLMATE THINKS I'M SEXY Cheech & Chong Earache My Eye Chef Chocolate Salty Balls Chef Love Gravy Chef No Substitute, Oh Kathy Lee Chef Simultaneous Chef & Meatloaf Tonight Is Right for Love Chef & No Substitute Oh Kathy Lee Chef (South Park) Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. -

De Representatie Van Leraren En Onderwijs in Populaire Cultuur. Een Retorische Analyse Van South Park

Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Psychologie en Pedagogische Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2014-2015 De representatie van leraren en onderwijs in populaire cultuur. Een retorische analyse van South Park Jasper Leysen 01003196 Promotor: Dr. Kris Rutten Masterproef neergelegd tot het behalen van de graad van master in de Pedagogische Wetenschappen, afstudeerrichting Pedagogiek & Onderwijskunde Voorwoord Het voorwoord schrijven voelt als een echte verlossing aan, want dit is het teken dat mijn masterproef is afgewerkt. Anderhalf jaar heb ik op geregelde basis gezwoegd, gevloekt en getwijfeld, maar het overheersende gevoel is toch voldoening. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar veel tijd en moeite is ingekropen. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben waar ik toch wel fier op ben. Voldoening om een werk af te hebben dat ik zelfstandig op poten heb gezet en heb afgewerkt. Althans hoofdzakelijk zelfstandig, want ik kan er niet omheen dat ik regelmatig hulp heb gekregen van mensen uit mijn omgeving. Het is dan ook niet meer dan normaal dat ik ze hier even bedank. In de eerste plaats wil ik mijn promotor, dr. Kris Rutten, bedanken. Ik kon steeds bij hem terecht met vragen en opmerkingen en zijn feedback gaf me altijd nieuwe moed en inspiratie om aan mijn thesis verder te werken. Ik apprecieer vooral zijn snelle en efficiënte manier van handelen. Nooit heb ik lang moeten wachten op een antwoord, nooit heb ik vele uren zitten verdoen op zijn bureau. Bedankt! Ten tweede wil ik ook graag Ayna, Detlef, Diane, Katoo, Laure en Marijn bedanken voor deelname aan mijn focusgroep. Hun inzichten hebben ervoor gezorgd dat mijn analyses meer gefundeerd werden, hun enthousiasme heeft ertoe bijgedragen dat ik besefte dat mijn thesis zeker een bijdrage is voor het onderzoeksveld. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better.