PDVSA US Litigation Trust: What Creditors Should Know About the Trust, Its Claims and Its Implications for Venezuela’S Restructuring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hess Corporation

New Hampshire Competitive Natural Gas Supplier Renewal Application Hess Corporation — DM — 07-112 PUC 3003.01 (d) Each CNGS applicant shall re-register with the commission every 2 years by filing with the commission an application for renewal. Each CNGS applicant shall file an application for renewal at least 60 days prior to the expiration oftheir registration. (e) The CNGS shall include on each renewal application an update, including any changes, to all information contained in the previous application. Pursuant to PUC 3003.01(e) the following provides any and all updates to responses contained within Hess Corporation’s original registration submitted November 25, 2003, and approved February 19, 2004 and Hess Corporation’s Renewal Application submitted October 16, 2007. For each item within the original registration that has not changed it is indicated as such below. PUC 3001.01 (b) (1) Be signed by the CNGS Please see certification in Exhibit 9. (2) Include the following: a. The legal name of the applicant as well as any trade name(s) under which it intends to operate in this state; (Updated) Hess Corporation f/k/a Arnerada Hess Corporation Please see Exhibit 8. b. The applicant’s business address, if any, principal place of business, telephone number, facsimile number and email address; (Unchanged) One Hess Plaza Woodbridge, NJ 07095 Phone: (732) 750-6000 Fax: (732 750-6670 www.hess. corn c. The applicant’s place of incorporation; (Unchanged) The State ofDelaware. d. The names, titles, business addresses, telephone numbers and facsimile numbers of the applicant’s principal officers; (Updated) Please See Exhibit 1. -

Petrobras: the Unique Structure Behind Latin America's Best

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Energy Dialogue, White Papers and Latin American Energy Policy, Regulation and Reports Dialogue 2011 Petrobras: The niqueU Structure behind Latin America's Best Performing Oil Company Genaro Arriagada Chris Cote Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/la_energy_dialog Recommended Citation Arriagada, Genaro and Chris Cote. "Petrobras: The niqueU Structure behind Latin America's Best Performing Oil Company." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/la_energy_dialog/179 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin American Energy Policy, Regulation and Dialogue at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Energy Dialogue, White Papers and Reports by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAS VOLUME 20 • SPRING 2011 • HTTP://LACC.FIU.EDU Energy Challenges in the Americas Hemisphere VOLUME 20 • SPRING 2011 • HTTP://LACC.FIU.EDU IN THIS ISSUE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 3 LETTER FROM THE GUEST EDITORS 4 FEATURES Leading Energy Policy Issues in Latin America Genaro Arriagada 6 Energy Conflicts: A Growing Concern Patricia I. Vásquez 12 in Latin America Latin America’s Nuclear Future Jorge Zanelli Iglesias 16 REPORTS What Climate Change Means Paul Isbell 19 for Latin America Central America’s Energy Challenges Cristina Eguizábal 21 Why the United States and Cuba Jorge Piñón 24 Collaborate Challenges of Designing an Optimal Petroleum Roger Tissot 26 Fiscal Model in Latin America Petrobras: The Unique Structure behind Genaro Arriagada and Chris Cote 29 Latin America’s Best Performing Oil Company COMMENTARIES Argentina’s Energy Pricing Challenges Pablo Fernández-Lamela 32 Energy Consumption: Challenges and Heidi Jane Smith 33 Opportunities of Urbanization PetroCaribe: Welcome Relief for an Chris Cote 34 Energy-Poor Region SUGGESTED FURTHER READING 36 Hemisphere EDITORIAL STAFF Founding Editor Anthony P. -

2Q13 Dividend

600 North Dairy Ashford Road Houston, TX 77079-1175 Media Relations: 281-293-1149 www.conocophillips.com/media NEWS RELEASE Aug. 20, 2018 ConocoPhillips Signs $2 Billion Settlement Agreement with PDVSA on ICC Arbitration Award HOUSTON – ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP) announced today that it has entered into a settlement agreement with Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), the Venezuelan state-owned oil company, to recover approximately $2 billion, the full amount awarded to ConocoPhillips by an arbitral tribunal constituted under the rules of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), plus interest through the payment period. PDVSA has agreed to recognize the ICC judgment and make initial payments totaling approximately $500 million within a period of 90 days from the time of signing. The balance of the settlement is to be paid quarterly over a period of 4.5 years. As a result of the settlement, ConocoPhillips has agreed to suspend its legal enforcement actions of the ICC award, including in the Dutch Caribbean. ConocoPhillips has ensured that the settlement meets all appropriate U.S. regulatory requirements, including any applicable sanctions imposed by the U.S. against Venezuela. Further details of the agreement are confidential. On April 25, 2018, the ICC tribunal awarded ConocoPhillips approximately $2 billion arising out of PDVSA’s failure to uphold its contractual commitments. The award relates to the unlawful expropriation of ConocoPhillips’ investments in the Hamaca and Petrozuata heavy crude oil projects in Venezuela in 2007 and other pre- expropriation fiscal measures. The ICC arbitration award is final and binding upon the parties. Additionally, ConocoPhillips has a separate and independent legal action pending against the government of Venezuela before a tribunal under the auspices of the World Bank's International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). -

U.S. Sanctions Venezuelan Oil Industry

ALERT MEMORANDUM U.S. Sanctions Venezuelan Oil Industry January 29, 2019 On January 28, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), in consultation with the U.S. If you have any questions concerning Department of State, determined that persons operating in Venezuela’s oil this memorandum, please reach out to your regular firm contact or the sector are subject to sanctions under Executive Order (“E.O.”) 13850. As following authors a result, OFAC concurrently designated Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PdVSA”) as a specially designated national (“SDN”) pursuant to E.O. WASHINGTON 13850 for operating within this sector. Effective immediately, PdVSA is Paul Marquardt now included on OFAC’s list of SDNs (the “SDN List”) and all property +1 202 974 1648 and interests in property of PdVSA subject to U.S. jurisdiction are now [email protected] blocked. Nathanael Kurcab OFAC simultaneously amended previously-issued General License 3 by +1 202 974 1652 [email protected] issuing General License 3A (“GL 3A”) and issued eight (8) new general licenses related to the designation of PdVSA. Newly issued General Licenses 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14—which are summarized further below—are intended to mitigate the impact of the designation of PdVSA outside of Venezuela by providing certain exemptions and time-limited authorizations for certain transactions and activities related to PdVSA and its subsidiaries. KEY TAKEAWAYS At a high level, as a result of OFAC’s designation of PdVSA and issuance of related general licenses: • all assets of PdVSA and its direct and indirect subsidiaries owned 50% or more by PdVSA or other SDNs (in the aggregate) within U.S. -

Royal Dutch Shell and Its Sustainability Troubles

Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 Albert ten Kate May 2011 1 Colophon Title: Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 May 2011. This report is made on behalf of Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) Author: Albert ten Kate, free-lance researcher corporate social responsibility Pesthuislaan 61 1054 RH Amsterdam phone: (+31)(0)20 489 29 88 mobile: (+31)(0)6 185 68 354 e-mail: [email protected] 2 Contents Introduction 4 Methodology 5 Cases: 1. Muddling through in Nigeria 6 1a) oil spills 1b) primitive gas flaring 1c) conflict and corruption 2. Denial of Brazilian pesticide diseases 14 3. Mining the Canadian tar sands 17 4. The bitter taste of Brazil's sugarcane 20 4a) sourcing sugarcane from occupiers of indigenous land 4b) bad labour conditions sugarcane harvesters 4c) massive monoculture land use 5. Fracking unconventional gas 29 6. Climate change, a business case? 35 7. Interfering with politics 38 8. Drilling plans Alaska’s Arctic Ocean 42 9. Sakhalin: the last 130 Western Gray Whales 45 10. The risky Kashagan oil field 47 11. A toxic legacy in Curaçao 49 12. Philippines: an oil depot amidst a crowd of people 52 3 Introduction Measured in revenue, Royal Dutch Shell is one of the biggest companies in the world. According to its annual report of 2010, its revenue amounted to USD 368 billion in 2010. Shell produces oil and gas in 30 countries, spread over the world. -

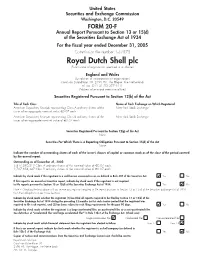

2005 Annual Report on Form 20-F

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2005 Commission file number 1-32575 Royal Dutch Shell plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) Carel van Bylandtlaan 30, 2596 HR, The Hague, The Netherlands tel. no: (011 31 70) 377 9111 (Address of principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered American Depositary Receipts representing Class A ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value €0.07 each American Depositary Receipts representing Class B ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value of €0.07 each Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act None Securities For Which There is a Reporting Obligation Pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. Outstanding as of December 31, 2005: 3,817,240,213 Class A ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. 2,707,858,347 Class B ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Venezuela and Petróleos De Venezuela SA (PDVSA)

Country Report: Venezuela and Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA) Carlos A. Molina, Associate Professor at IESA Business School Associate Professor at IESA Business School in Venezuela since 2005, Carlos Molina was previously Assistant Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and the University of Texas at San Antonio. Carlos earned his Ph.D. in Finance (2002) from the University of Texas at Austin, MBA (1994) from IESA, and BS in Civil Engineering from the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (1990) in Caracas. As a country, Venezuela has one of the largest oil reserves in the world; new discoveries, like the Orinoco oil belt fields, may mean it will someday ascend to the #1 spot. Like most countries with large oil reserves, Venezuela’s oil assets are managed by a state- owned company. This energy brief focuses on the recent history of oil production and investment within Venezuela, as well as its opportunities and challenges. History and Founding of PDVSA Before 1976, oil exploration companies, such as Creole, Shell, and others, were dedicated to the exploration, production, and refinement of oil in Venezuela, while the State limited itself to receiving taxes and royalties for those activities. However, after the increases in oil prices from $4 to $12 a barrel in the early 1970s, the Venezuelan government decided to nationalize the oil industry, and Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA) was born as a vertically-oriented merger of foreign oil companies with operations in Venezuela at that time. After the nationalization, PDVSA privately undertook all oil activities in Venezuela until 1992. -

The Orinoco Oil Belt - Update

THE ORINOCO OIL BELT - UPDATE Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Orinoco Oil Belt Assessment Unit (blue line); the La Luna-Quercual Total Petroleum System and East Venezuela Basin Province boundaries are coincident (red line). Source: http://geology.com/usgs/venezuela-heavy-oil/venezuela-oil-map-lg.jpg Update on extra heavy oil development in Venezuela 2012 is likely to be a crucial year for the climate, as Venezuela aims to ramp up production of huge reserves of tar sands-like crude in the eastern Orinoco River Belt.i Venezuela holds around 90% of proven extra heavy oil reserves globally, mainly located in the Orinoco Belt. The Orinoco Belt extends over a 55,000 Km2 area, to the south of the Guárico, Anzoátegui, Monagas, and Delta Amacuro states (see map). It contains around 256 billion barrels of recoverable crude, according to state oil company PDVSA.ii Certification of this resource means that, in July 2010, Venezuela overtook Saudia Arabia as the country with the largest oil reserves in the world.iii Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state oil company, is also now the world’s fourth largest company.iv Development of the Orinoco Belt is the keystone of the Venezuelan government’s future economic plans – oil accounts for 95% of the country’s export earnings and around 55% of the federal budget.v The government has stated that it is seeking $100 billion of new investment to develop the Belt.vi President Chavez announced at the end of 2011 that the country intended to boost its oil output to 3.5 million barrels a day by the end of 2012. -

PCA Case No. 2013-34 in the MATTER of an ARBITRATION

PCA Case No. 2013-34 IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION PURSUANT TO THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF BARBADOS AND THE REPUBLIC OF VENEZUELA FOR THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF INVESTMENTS -between- VENEZUELA US, S.R.L. (the “Claimant”) -and- THE BOLIVARIAN REPUBLIC OF VENEZUELA (the “Respondent”, and together with the Claimant, the “Parties”) ________________________________________________________ PARTIAL AWARD (JURISDICTION AND LIABILITY) ________________________________________________________ ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL: H.E. Judge Peter Tomka (Presiding Arbitrator) The Honourable L. Yves Fortier PC CC OQ QC Professor Marcelo Kohen SECRETARY TO THE TRIBUNAL: Mr. Martin Doe Rodriguez REGISTRY: Permanent Court of Arbitration 5 February 2021 PCA Case No. 2013-34 Partial Award Page 2 of 83 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE PARTIES ............................................................................................................................. 6 II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................ 6 A. COMMENCEMENT OF THE ARBITRATION ......................................................................... 6 B. CONSTITUTION OF THE TRIBUNAL .................................................................................... 8 C. INITIAL PROCEDURAL STEPS ............................................................................................. 8 D. BIFURCATION OF THE PROCEEDINGS ............................................................................... 9 E. FIRST -

2008 Annual Report OUR COMPANY

2008 Annual Report OUR COMPANY Hess Corporation is a leading global independent energy company engaged in the exploration for and production of crude oil and natural gas, as well as in refining and marketing refined petroleum products, natural gas and electricity. Our strategy is to build a company that will sustain profitable growth and create significant shareholder value. We are committed to meeting the highest standards of corporate citizenship by protecting the health and safety of our employees, safeguarding the environment and making a positive impact on the communities in which we do business. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Financial Highlights 2 Letter to Stockholders 4 Exploration and Production 8 Marketing and Refining 10 Corporate and Social Responsibility 12 Board of Directors and Corporate Officers Cover: Shenzi Development, Gulf of Mexico FINANCIAL AND OPERATING HIGHLIGHTS Amounts in millions, except per share data 2008 2007 FINANCIAL – FOR THE YEAR Sales and other operating revenues $ 41,165 $ 31,647 Net income $ 2,360 $ 1,832 Net income per share diluted $ 7.24 $ 5.74 Common stock dividends per share $ 0.40 $ 0.40 Net cash provided by operating activities $ 4,567 $ 3,507 Capital and exploratory expenditures $ 4,828 $ 3,926 Weighted average diluted shares outstanding 325.8 319.3 FINANCIAL – AT YEAR END Total assets $ 28,589 $ 26,131 Total debt $ 3,955 $ 3,980 Stockholders’ equity $ 12,307 $ 9,774 Debt to capitalization ratio(a) 24.3% 28.9% Common stock price $ 53.64 $ 100.86 OPERATING – FOR THE YEAR Production – net Crude oil and natural gas liquids (thousands of barrels per day) United States 42 41 International 224 234 Total 266 275 Natural gas (thousands of Mcf per day) United States 78 88 International 611 525 Total 689 613 Barrels of oil equivalent (thousands of barrels per day) 381 377 Marketing and Refining (thousands of barrels per day) Refining crude runs—HOVENSA L.L.C.(b) 221 227 Refined products sold 472 451 (a) Total debt as a percentage of the sum of total debt and stockholders’ equity. -

Background Reference: Venezuela

Background Reference: Venezuela Last Updated: January 7, 2019 Overview Venezuela’s output has fallen significantly since global crude oil prices fell from their peak in mid-2014. The production declines have been especially acute since mid-2016, with Venezuela’s crude oil output falling by 755,000 barrels per day (b/d) between June 2016 and May 2018. U.S. Energy Information Administration 1 The Venezuelan economy relies heavily on crude oil. Crude oil revenues have fallen significantly, falling to $22 billion in 2016, according to EIA’s estimates of Venezuela’s net oil export revenues. In 2011, Venezuela’s net oil export revenues were more than $73 billion (in 2016 dollars). The chronic problems in Venezuela’s oil industry that led to the steep production declines are unlikely to change any time soon. Venezuela’s economic and political instability The Venezuelan government is facing high levels of debt and hyperinflation. During the last quarter of 2017, Venezuela was late in making some bond payments, and the main rating agencies declared the country in selective default. During 2018, more than $9 billion in bond payments will come due, raising the possibility of a general default. In addition to the approximately $64 billion of debt in traded bonds, Venezuela owes $26 billion to creditors and $24 billion in commercial loans, according to Torino Capital estimates, although some estimates place Venezuelan debt at $150 billion.1 Venezuela’s economy contracted by nearly 9% in 2017, based on estimates from Oxford Economics. Although the Venezuelan government has not published any economic data in more than two years, Venezuela’s National Assembly reported in mid-March 2018 that inflation was more than 6,000% between February 2017 and February 2018. -

Crisis Overview: Petrobras

CRISIS OVERVIEW: PETROBRAS Petrobras is the state oil company in Brazil. Petrobras’s oil production areas are exclusively in South America, but currently have no claims in the Guyana-Suriname Basin. The company also has refineries in Texas and Japan, and joint ventures with multiple countries in West Africa. In May of 2019, Chevron bought a Texas oil refinery from Petrobras for $350 million. The site was the center of the Brazilian government’s corruption investigation into Petrobras, and the company had paid more than $1 billion for the plant before it took over ownership in 2012. Petrobras ended up paying $912 million in restitution to the Brazilian Government, US Government, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Going forward, Chevron must monitor the actions of Petrobras as it relates to its past in Brazil and the potential for future conflict in the Guyana-Suriname Basin. GUYANA-SURINAME BASIN OVERVIEW The Guyana-Suriname Basin is the world’s last major unexplored oil basin. The basin has attracted companies such as Shell, Total, and Mobil since the 1940s, who completed major geological surveying and drilled test wells in Guyanese waters. In Suriname’s waters, the state oil company Staatsolie is a dwarf of production, only drilling a little over 16,000 barrels a day. In Guyanese waters alone, Exxon and Hess estimate that reserves in the Stabroek block off Guyana alone possess over 5,000 MMboe (millions of barrel of oil equivalent). These major discoveries have led to international investment in the Guyana-Suriname Basin, reducing the risk of committing great resources to such uncharted territory.