English (PDF Document)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

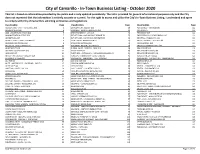

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Talking Book Topics November-December 2016

Talking Book Topics November–December 2016 Volume 82, Number 6 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2016 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. -

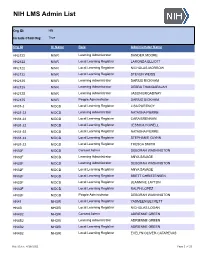

NIH LMS Admin List

NIH LMS Admin List Org ID: HN Include Child Org: True Org ID IC Name Role Administrator Name HN2122 NINR Learning Administrator SANDER MOORE HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar LARONDA ELLIOTT HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar NICHOLAS MORROW HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar STEVEN WEISS HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator DARIUS BICKHAM HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator DEBRA THANGARAJAH HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator JASON BROADWAY HN2125 NINR People Administrator DARIUS BICKHAM HN31-2 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar LISA PORTNOY HN31-22 NIDCD Learning Administrator NATASHA PIERRE HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar CARA BRENNAN HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar JESSICA HOWELL HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar NATASHA PIERRE HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar STEPHANIE GLYNN HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar TRESCA SMITH HN32F NIDCD Content Admin DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN32F NIDCD Learning Administrator ANYA SAVAGE HN32F NIDCD Learning Administrator DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar ANYA SAVAGE HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar BRETT CHRISTENSEN HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar JEANNINE LAYTON HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar RALPH LOPEZ HN32F NIDCD People Administrator DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN41 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar YASMEEN BECKETT HN4B NHGRI Local Learning Registrar NICHOLAS LOGAN HN4B2 NHGRI Content Admin ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Learning Administrator ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar EVELYN -

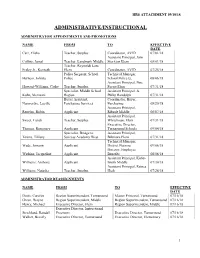

Administrative/Instructional

HRS ATTACHMENT 09/10/18 ADMINISTRATIVE/INSTRUCTIONAL ADMINISTRATOR APPOINTMENTS AND PROMOTIONS NAME FROM TO EFFECTIVE DATE Carr, Elisha Teacher, Surplus Coordinator, AVID 07/01/18 Assistant Principal, John Collins, Jamal Teacher, Landmark Middle Stockton Elem 08/01/18 Teacher, Reynolds Lane Fraley Jr., Kenneth Elem Coordinator, AVID 07/25/18 Police Sergeant, School Technical Manager, Harness, Johnny Police School Police Lt. 08/06/18 Assistant Principal, Pine Howard-Williams, Cathy Teacher, Surplus Forest Elem 07/31/18 Specialist, Middle School Assistant Principal, A. Kohn, Memsani Region Philip Randolph 07/31/18 Buyer Assistant, Coordinator, Buyer, Nasworthy, Lucille Purchasing Services Purchasing 08/20/18 Assistant Principal, Renelus, Robin Applicant Ribault Middle 08/07/18 Assistant Principal, Sweet, Candi Teacher, Surplus Whitehouse Elem 07/31/18 Executive Director, Thomas, Rosemary Applicant Turnaround Schools 09/04/18 Specialist, Bridge to Assistant Principal, Towns, Tiffany Success Academy West Biltmore Elem 07/31/18 Technical Manager, Wade, Jowann Applicant District Nursing 09/06/18 Director, Employee Watkins, Jacqueline Applicant Benefits 08/06/18 Assistant Principal, Kirby- Williams, Anthony Applicant Smith Middle 07/30/18 Assistant Principal, Raines Williams, Natasha Teacher, Surplus High 07/26/18 ADMINISTRATOR REASSIGNMENTS NAME FROM TO EFFECTIVE DATE Davis, Carolyn Region Superintendent, Turnaround Master Principal, Turnaround 07/16/18 Green, Wayne Region Superintendent, Middle Region Superintendent, Turnaround 07/16/18 Henry, -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1997

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1997 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 Ryan 795 1 Emma 752 2 Andrew 761 2 Chloe 743 3 Jack 759 3 Rebecca 713 4 Ross 700 4 Megan 645 5 James 638 5 Lauren 631 6 Connor 590 6 Amy 623 7 Scott 586 7 Shannon 552 8 Lewis 568 8 Caitlin 550 9 David 560 9 Rachel 517 10 Michael 557 10 Hannah 480 11 Jordan 554 11 Sarah 471 12 Liam 550 12 Sophie 433 13 Daniel 546 13 Nicole 378 14 Cameron 526 14 Erin 362 15 Matthew 509 15 Laura 348 16 Kieran 474 16 Emily 289 17 Jamie 452 17 Jennifer 277 18 Christopher 440 18 Courtney 276 19 Kyle 421 19= Kirsty 258 20 Callum 419 19= Lucy 258 21 Craig 418 21 Danielle 257 22 John 396 22= Katie 252 23 Dylan 394 22= Louise 252 24 Sean 367 24 Heather 250 25 Thomas 348 25 Rachael 221 26 Adam 347 26 Eilidh 214 27 Calum 335 27 Holly 213 28 Mark 310 28 Samantha 208 29 Robert 297 29 Stephanie 202 30 Fraser 292 30= Kayleigh 194 31 Alexander 288 30= Zoe 194 32 Declan 284 32 Melissa 189 33 Paul 266 33 Claire 182 34 Aaron 260 34 Chelsea 180 35 Stuart 257 35 Jade 176 36 Euan 252 36 Robyn 173 37 Steven 243 37 Jessica 160 38 Darren 231 38= Aimee 159 39 William 228 38= Gemma 159 40 Lee 226 38= Nicola 159 41= Aidan 207 41 Hayley 156 41= Stephen 207 42= Lisa 155 43 Nathan 205 42= Natalie 155 44 Shaun 198 44 Anna 151 45 Ben 195 45 Natasha 148 46 Joshua 191 46 Charlotte 134 47 Conor 176 47 Abbie 132 48 Ewan 174 -

Fall 10 28#2Cs4.Indd

Volume XXVIII • Number 2 • 2010 Historical Magazine of The Archives Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary 1855 Knollcrest Circle SE Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546 pagepage 10 page 20 (616) 526-6313 Origins is designed to publicize 2 From the Editor 14 Back-and-Forth Wanderlust: and advance the objectives of The Autobiography of Jacob The Archives. These goals 4 An American Flyer Remem- Koenes include the gathering, bered: Martin Douma Jr., organization, and study of 1920–1944 historical materials produced by Richard H. Harms the day-to-day activities of the Christian Reformed Church, its institutions, communities, and people. Richard H. Harms Editor Hendrina Van Spronsen Circulation Manager Tracey L. Gebbia Designer H.J. Brinks Harry Boonstra Janet Sheeres Associate Editors James C. Schaap Robert P. Swierenga Contributing Editors HeuleGordon Inc. pagepage 28 page 39 Printer 25 One Heritage — 35 “When I Was a Kid,” part II Two Congregations: Meindert De Jong, with The Netherlands Reformed in Judith Hartzell Grand Rapids, 1870 – 1970 Cover photo: 44 Book Notes Saakje and Jacob Koenes with their helpers Janet Sjaarda Sheeres on the Groenstein farm. 46 For the Future upcoming Origins articles 47 Contributors from the editor . now available and personal accounts totaled more than 34,000 entries, the are being distributed via the internet. data are available in two alphabetical- Janet Sheeres details the history of the ly sorted PDF formatted fi les, A-L and Netherlands Reformed congregations, M-Z which are available at http://www. primarily in West Michigan, whose calvin.edu/hh/Banner/Banner.htm. With experiences had previously been these two fi les, this site now provides overshadowed by the stories of the access to all such data for the years Time to Renew Your Subscription larger Reformed Church in America 1985-2009. -

Closely Intertwined for Centuries

IllusterMarch 2021 How can we make sure Utrecht stays accessible, healthy and inclusive? Creating tomorrow, together with Mapping air quality our alumni UNIVERSITY AND CITY Closely intertwined for centuries Professor of University History Leen Dorsman explains FOREWORD Anniversary Contents during a pandemic The inter- 22 ‘I decided to his year, Utrecht University (UU) and connected UMC Utrecht will be celebrating 385 years only write things of science and academia in Utrecht. Due to COVID 19 all the get-togethers and 10 nature of I understood celebrations will have to be held in an Talternative manner or be postponed until later. VR headsets for University myself’ What a contrast to the festivities in 1986. It was my first ‘real’ job: organising the celebration of the 350th anniver- patients with sary of our university. In addition to experienced staff and city and clever academics, young people nearing graduation — brain damage myself included — were asked to help with the organisa- tion as well. I think of that period often. It was hard graft: Rutger Bregman a hectic schedule, deadlines, juggling multiple tasks and Alumnus of the Year working late often. But there was also plenty of humour and a strong sense of camaraderie. I gained lifelong friendships during that time. At the opening, Queen Beatrix specifically wanted to meet the young employees. We were so very proud. When I look at the picture taken of us together, it always brings back happy memories. Like then, the current anniversary year is Publication details 12 4 The big picture all about the connection to society, 6 Short with ‘Creating tomorrow together’ Illuster is a Utrecht University and Utrecht University Fund The Utrecht publication. -

Death Certificate Index - Marion County (1917-1939) Query 5/15/2015

Death Certificate Index - Marion County (1917-1939) Query 5/15/2015 Name Birth Date Birth Place Death Date County Mother's Maiden Name Number Box Aalbers, Kenneth Max 03 Jan. 1938 Iowa 23 Mar. 1938 Marion Bradburn J63-0041 D2871 Aalbers, Mareneus 19 Apr. 1919 Iowa 13 June 1921 Marion Poortinga 63-0015 D2329 Aalbers, Marinus 17 May 1867 Holland 14 Nov. 1933 Marion D63-0208 D2704 Aalbers, Marinus (Mrs.) 08 Aug. 1867 Netherlands 17 Jan. 1930 Marion Wichthart A63-0022 D2620 Abbott, Beadie Jane c.12 Nov 1893 Nebraska 14 Aug. 1929 Marion Savage 63-2101 D2331 Abbott, Daniel 18 Oct. 1891 Kansas 03 July 1928 Marion Smith 63-1846 D2331 Abbott, John Lavern 18 Nov. 1924 Idaho 30 Mar. 1927 Marion 63-1515 D2331 Abbott, Lee Marion c.03 Nov. 1891Texas 25 Aug. 1921 Marion 63-0018 D2329 Abington, Minnie B. 1875 Virginia 26 Feb. 1939 Marion Unknown 63-0025 D2905 Adams (Baby Girl) 15 May 1938 Iowa 16 May 1938 Marion Pope J63-0083 D2871 Adams, Elmira C. 03 Aug. 1844 New York 28 Apr. 1936 Marion Quackinbush G63-0082 D2802 Adams, John 21 Oct. 1840 Ohio 10 Mar. 1919 Marion Geohan 63-2073 D2328 Adams, John Quincy 08 July 1851 Indiana 30 Apr. 1932 Marion Forsy C63-0082 D2674 Adams, Wesley M. 08 Mar. 1851 Indiana 18 May 1918 Marion Founcy 63-1781 D2328 Adamson, Cecil 28 June 1919 Iowa 29 June 1919 Marion Jones 63-2157 D2328 Adkison, Amanda C. 20 Sept. 1837 Ohio 12 Mar. 1926 Marion Thomas 63-1288 D2330 Adkison, Dorsey 27 Feb. -

Gezinskaarten Ammerzoden – D

GEZINSKAARTEN AMMERZODEN – D DALEN Jan Dalen [j.g. uit Vianen] Maijke Mercelis van Puersom [uit Giessen] Huwelijk: 12 oktober 1660 Well / 22 december 1660 Ammerzoden DALEN, VAN Huibertus van Dalen [geboorte: 12 januari 1860 Hedel, zoon van Johannis van Dalen en Geertruij Timmermans] [arbeider, slager] [overlijden: 25 december 1944 gemeente Ammerzoden] Johanna Dekkers [geboorte: 16 mei 1861 Wordragen, dochter van Teunis Dekkers en Maria Hansen] [1e huwelijk: 9 mei 1884 Ammerzoden met Adrianus van Tiel] [overlijden: 24 december 1944 gemeente Ammerzoden] Huwelijk: 20 juni 1895 Ammerzoden Kinderen: 1. Johannes Adrianus, geboorte: 3 mei 1896 Ammerzoden, overlijden: 15 september 1896 Ammerzoden 2. Maria Geertruida, geboorte: 20 mei 1897 Ammerzoden, huwelijk: 17 augustus 1922 Eindhoven met Franciscus van de Weijdeven 3. Adriana Johanna, geboorte: 13 mei 1898 Ammerzoden, overlijden: 27 juli 1898 Ammerzoden 4. Geertruida Johanna, geboorte: 14 juli 1899 Ammerzoden, huwelijk: 15 mei 1924 Eindhoven met Jozef Heesakkers 5. Adrianus Antonius, geboorte: 22 juni 1901 Ammerzoden, overlijden: 30 november 1901 Ammerzoden 6. Wilhelmina Adriana, geboorte: 30 augustus 1902 Ammerzoden, huwelijk: 22 oktober 1926 Eindhoven met Antonius Johannes Maria van Ruth Jielis van Dalen [geboorte: 28 juni 1819 Brakel, zoon van Jacob van Dalen en Maria van der Vliet] [visser, dagloner] [overlijden: 18 november 1894 Brakel] Roelanda de Koning [geboorte: 16 december 1827 Well, dochter van Jan de Koning en Petronella van Hees] [overlijden: 7 oktober 1894 Brakel] Huwelijk: 1 mei 1851 Brakel Kinderen: 1. Johannes, geboorte: 15 september 1851 Brakel, dagloner, overlijden: 28 december 1867 Brakel 2. Maria Pieternella, geboorte: 23 januari 1853 Brakel, overlijden: 16 maart 1868 Brakel 3. Jan, geboorte: 3 februari 1854 Brakel, overlijden: 24 maart 1855 Brakel 4. -

SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT and RESTORATION in the MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA REGION Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations

SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND RESTORATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA REGION Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations Fall 2019 Environmnt, Nturl Rsourcs & Blu Econom 64270_SLM_CVR.indd 3 11/6/19 12:38 PM SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND RESTORATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA REGION ISSUES, CHALLENGES, AND RECOMMENDATIONS 10116-SLM_64270.indd 1 11/19/19 1:37 PM © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Direc- tors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denomina- tions, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2019. Sustainable Land Management and Restoration in the Middle East and North Africa Region—Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations. Washington, DC. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: World Bank Publications The World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Fax: 202-522-2625 10116-SLM_64270.indd 2 11/19/19 1:37 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . -

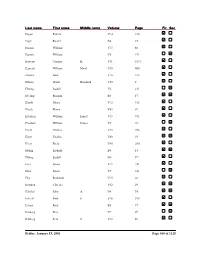

Last Name First Name Middle Name Volume Page Fir Sec Eagan Patrick V14 330

Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Eagan Patrick V14 330 Eagle Rudolf B4 F8 Eamon William V15 66 Eamon William V5 371 Eastcott Caroline H. V31 5174 Eastcott William Meril V30 400 Ebaven John V16 375 Ebbers Gerrit Hendrick V50 8 Ebbing Ludolf V2 211 Ebeling Herman B4 F7 Eberle Henry V15 315 Eberle Henry V49 59 Eberlein William Ernest V15 571 Eberlein William Ernest V7 39 Ebert Charles V23 496 Ebert Charles V60 59 Ebert Erick V30 250 Ebling Ludholf B4 F8 Ebling Ludolf B4 F7 Ebre Johan V17 251 Ebro Johan V7 531 Eby Benjamin V15 26 Ebyinck Clarence V82 29 Echelof John A. B4 F8 Echerk Nick S. V16 519 Eckart Fred B4 F7 Eckberg Nels V9 49 Eckberg Nels T. V18 86 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 308 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Eckberg Oscar V26 225 Eckberg Oscar V65 176 Eckelof John A. B4 F6 Eckert Albert B4 F6 Eckert Albert B4 F7 Eckert Albert V2 32 Eckert Frank B7 94 Eckert Fred V2 13 Eckford Martin V17 391 Eckford Martin V17 393 Eckhardt William B4 F8 Eckhardt William V2 500 Eckielof John A. V3 36 Ecklisdafer Frederick V26 46 Ecklisdafer Frederick V66 3 Ecklund Carl August V24 115 Eckman Nick V2 568 Eckstram John C. B4 F6 Eckstrom Anders V14 586 Eckstrom Carl A. V8 175 Eckstrum Edwin C. V2 93 Eddy Charles V5 75 Ede Edwin V16 47 Edelstein Charles V16 438 Edema A. B4 F6 Edema James B4 F8 Edema James V2 448 Eden Paul V25 426 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 309 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Edenstrom Axel B4 F8 Edenstrom Axel l V2 228 Edewaard Herman C. -

The Ancestry and Posterity of Cornelius Henry Tiebout of Brooklyn

W-i tf 5: I "7 Di 558 1 O"i 'If ¦«**? [;< s= '•*'^««, r f S7 JS? t! &5i IHS^{ mfmst! ;*? C ' -^sia'iaffj?Ja ! k*^ :'?sM£ •lafe.^ i*t 5 j£^??f a'f » *s :"^Si' i 1 tit |«. f?a?J #:-< E^ E^ E^* E^* In E** Em E^* 14: E»* =*** ~ __— i <i =» ? a 32 Mg < o 5 ' ' =«* g s § E* 8 S =IA E^ i« = M =—• THE ANCESTRY AND POSTERITY OF CORNELIUS HENRY TIEBOUT OF BROOKLYN Copy No. **/, PRESENTED TO Jfr£&&€££</ /^^.^L / With the Compliments of PRINTED FOR PRIVATE DISTRIBUTION 1 \* *%* Itis a pleasure to state as a foreword that itis solely because of the interest in and knowledge of matters genea logical of Mr.Francis V.Morrell, a son of one of my former employers, that this work has been produced. To him we are indebted for most all of the documentary information, the arrangement of the book and its complete index, as well as the careful editing of fragmentary family records and the solution of perplexing problems of descent. 2 TIEBOUT This name is Teutonic, appearing as Tybalt, meaning people's prince. Itis found in several forms, among them the Danish, Theobald; Dutch, Tiebout; French, Thibaut; German, Dietbold, and Italian, Teobaldo. It has also appeared Thieboult. STANDARD DICTIONARY. The following spellings are found inAmerican records : Tybout, Tibout, Tibouwt, Thibou, Tiebout, Tiebouwt, Tiebaut, Thibo, Teabout, Thebout, Thebaut, Thibout, Tebow, Tibouts, Tiboe, Tebou, Tebout, Tebow, Tebo, Thibe, Tibau and Thiboutszen, plural or possessive. The name was known in Flanders when the whole country was under French rule and the principal seat of the family was at Bruges; from thence the American branch sprung.