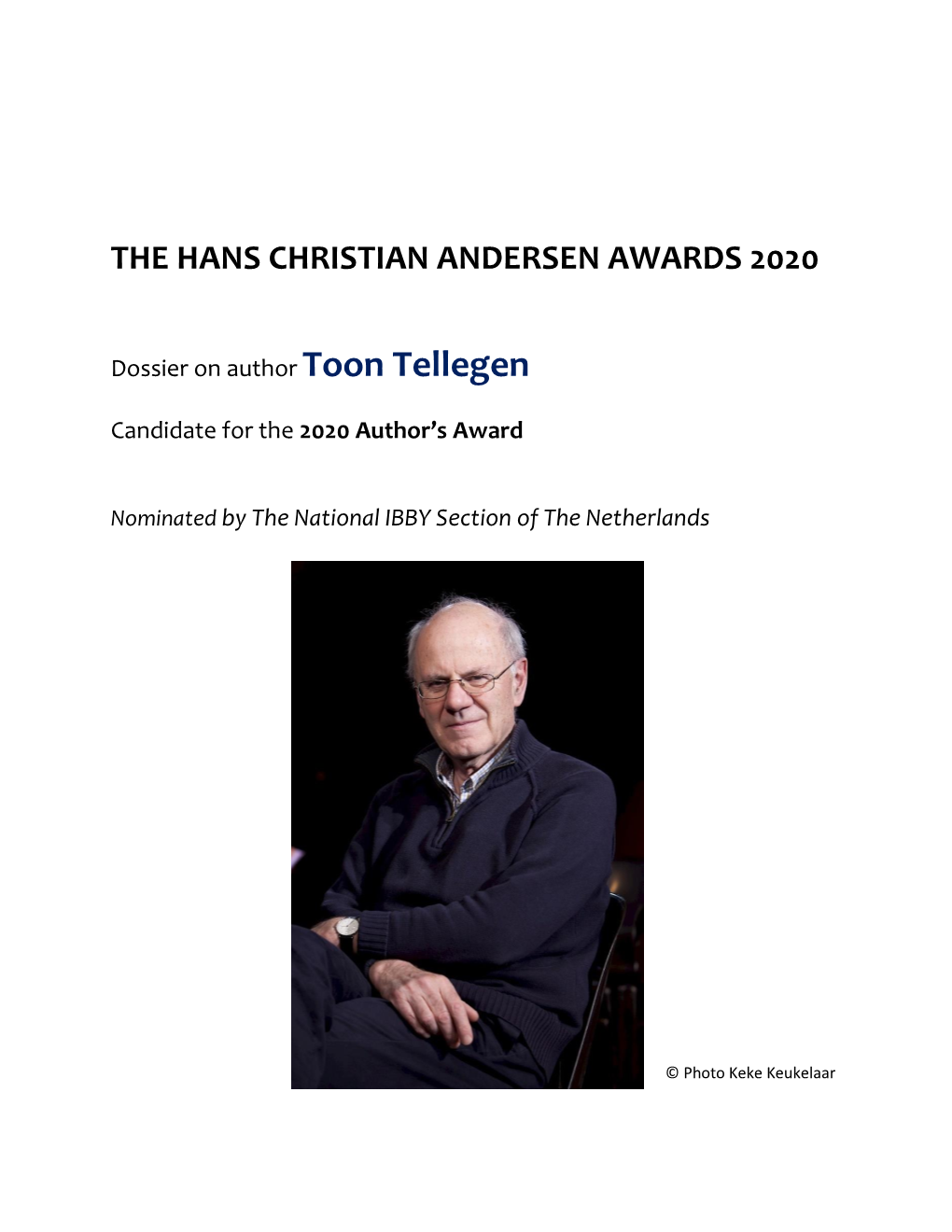

Toon Tellegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington, Wednesday, January 25, 1950

VOLUME 15 ■ NUMBER 16 Washington, Wednesday, January 25, 1950 TITLE 3— THE PRESIDENT in paragraph (a) last above, to the in CONTENTS vention is insufficient equitably to justify EXECUTIVE ORDER 10096 a requirement of assignment to the Gov THE PRESIDENT ernment of the entire right, title and P roviding for a U niform P atent P olicy Executive Order Pase for the G overnment W ith R espect to interest to such invention, or in any case where the Government has insufficient Inventions made by Government I nventions M ade by G overnment interest in an invention to obtain entire employees; providing, for uni E mployees and for the Administra form patent policy for Govern tion of Such P olicy right, title and interest therein (although the Government could obtain some under ment and for administration of WHEREAS inventive advances in paragraph (a), above), the Government such policy________________ 389 scientific and technological fields fre agency concerned, subject to the ap quently result from governmental ac proval of the Chairman of the Govern EXECUTIVE AGENCIES tivities carried on by Government ment Patents Board (provided for in Agriculture Department employees; and paragraph 3 of this order and herein See Commodity Credit Corpora WHEREAS the Government of the after referred to as the Chairman), shall tion ; Forest Service; Production United States is expending large sums leave title to such invention in the and Marketing Administration. of money annually for the conduct of employee, subject, however, to the reser these activities; -

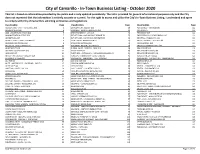

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Kijk Wijzer Naar Prentenboeken

Kijk Wijzer naar prentenboeken Naar een instrument voor een interpretatie van prentenboeken op basis van de interactie tussen beeld en tekst Loes Reichenfeld Begeleider: SNR 1276382 prof. dr. W.L.H. van Lierop-Debrauwer Tweede lezer: Maart 2018 dr. S.E. Van den Bossche Masterthesis, ter verdediging op 29 maart 2018 te Tilburg Master Jeugdliteratuur Kunst- en Cultuurwetenschappen “Zien en kijken is immers niet hetzelfde” Wim Pijbes1 “Elke bladzijde is een verhaaltje op zich” Annemarie van Haeringen2 “The words change the pictures and the pictures change the words” 3 Perry Nodelman Verantwoording: Deze thesis werd geschreven als afsluiting van de Master Kunst- en Cultuurwetenschappen/Jeugdliteratuur aan Tilburg University en wordt verdedigd op donderdag 29 maart 2018 te Tilburg. De voorzijde is gemaakt volgens richtlijnen voor de visuele identiteit uit het Huisstijlhandboek van Tilburg University: https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/nl/intranet/ondersteuning- werk/communicatie/huisstijl/vormgeving/huisstijlopmaak/download-huisstijlhandboek/ 1 Citaat van Wim Pijbes uit: De vorm blijft een mysterie (2017) Het Blad bij NRC, 13, p.21. 2 Naar een uitspraak van Annemarie van Haeringen tijdens de bespreking van Siens hemel op de Verdiepingsdag literatuureducatie met prentenboeken, georganiseerd door Artisjok & Olijfje, 23 februari 2018 te Den Bosch. 3 Citaat van Perry Nodelman uit: Words about Pictures (1988), p.220. Kijk Wijzer naar prentenboeken 1 INHOUDSOPGAVE SAMENVATTING ........................................................................................................................................ -

Onderzoeksrapport Kinderboekenonderzoek 2016

Juryrapport Kinderboekenonderzoek 2016 Juryrapport Kinderboekenonderzoek 2016 Inleiding De Bond tegen vloeken vraagt aandacht voor goed en respectvol taalgebruik. Grove vloeken en scheldwoorden passen volgens de Bond niet in een kinderboek. De kracht van woorden is niet te onderschatten. Het is belangrijk dat kinderen in aanraking komen met respectvol taalgebruik. Kinderen zijn beïnvloedbaar en volgen voorbeelden gemakkelijk na. Citaat van een leerling tijdens een gastles van KlasseTaal (onderwijsafdeling van de Bond tegen vloeken): Als je veel grove woorden leest, lijkt het alsof ze gewoon zijn. De Bond tegen vloeken voert jaarlijks in de maanden september en oktober een Kinderboeken- onderzoek uit. Het onderzoek beperkt zich tot de boeken die door de Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse Boek (CPNB) genomineerd zijn voor een prijs (Gouden Griffel) of die een bijzondere waardering (Vlag en Wimpel) hebben ontvangen. Uit onderzoek blijkt, dat 99% van de ouders hun kinderen corrigeert, wanneer ze ruwe woorden gebruiken. Het is bekend dat ouders en opvoeders via de Kijkwijzer gewezen wordt op de aanwezigheid van grove taal in tv-programma’s en films. Bij kinderboeken ontbreekt een dergelijke signalering. Het kinderboekenonderzoek van de Bond tegen vloeken heeft als zodanig een signaalfunctie. Aan het onderzoek werken verschillende juryleden mee. Zij screenen de boeken op vloeken en alle andere grove taal. Het is niet de bedoeling om een literair oordeel te vellen of de inhoud van het boek te beoordelen. De Bond tegen vloeken let op de hoeveelheid grove woorden, de mate waarin grove taal gebezigd wordt. Niet alle grove woorden zijn even zwaar. Er wordt mede gelet op de intensiteit van de grove taal. -

'Er Was Eens Een Waseens. De Jeugdliteratuur'

‘Er was eens een Waseens. De jeugdliteratuur’ Bregje Boonstra bron Bregje Boonstra, ‘Er was eens een Waseens. De jeugdliteratuur.’ In: Nicolaas Matsier (red.), Het literair klimaat 1986-1992. De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam 1993, p. 125-154 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/boon033erwa01_01/colofon.htm © 2004 dbnl / Bregje Boonstra 125 Bregje Boonstra Er was eens een Waseens De jeugdliteratuur Stel, er was een jeugdbibliothecaris die in 1958 naar Nieuw Zeeland was geëmigreerd. Nederlandse auteurs die toen al een duidelijk zichtbare plaats op de bibliotheekplanken hadden, waren An Rutgers van der Loeff, Jean Dulieu, Han Hoekstra en Annie M.G. Schmidt. Miep Diekmann begon net met publiceren. Over hun boeken verscheen in obscure krantehoekjes weleens iets dat een recensie moest voorstellen. Stel, dezelfde bibliothecaris kwam dertig jaar later nog eens terug - om precies te zijn op 27 september 1988 - en kocht NRC Handelsblad, voor een eerste snufje moederland. ‘Annie Schmidt gelauwerd,’ juicht het boven een foto op de voorpagina. Volgt een bericht over de uitreiking van de internationale Hans Christian Andersenmedaille in Oslo. Het zou een vervreemdende ervaring zijn geweest: alsof de tijd had stilgestaan - nog steeds Annie M.G.? - én vooruit was gehold - nu is zij voorpaginanieuws, in een stukje met driemaal de omvang van vroegere boekbeoordelingen. Dit krantebericht zegt zeker iets over de Nederlandse jeugdliteratuur vanaf het midden van de jaren tachtig. De naam van Annie Schmidt is op ieders lip en niet omdat ze zulke mooie nieuwe boeken heeft geschreven. In 1987 verschijnt de kloeke verzamelbundel Ziezo, waarin de auteur de definitieve omvang van het corpus van haar kinderverzen vaststelt op driehonderdzevenenveertig. -

Onderwijsrecensies Basisonderwijs 2015 - 1 4-6 Jaar Prentenboeken

Onderwijsrecensies basisonderwijs 2015 - 1 4-6 jaar Prentenboeken 2014-29-3450 Bon, Annemarie • Hiep hiep Haas! Niveau/leeftijd : AK Winkelprijs : € 14.95 Hiep hiep Haas! / Annemarie Bon ; met illustraties van Gertie Jaquet. - Amsterdam : Bijzonderheden : J1/J2/EX/ Moon, [2014]. - 26 ongenummerde pagina's : illustraties ; 30 cm Volgnummer : 44 / 173 ISBN 978-90-443-4521-6 Nog een nachtje slapen en dan is Haas jarig. Een verjaardagsfeest organiseren kost veel energie en tijd. Als Haas om acht uur naar bed gaat is hij best moe, maar slapen kan hij niet. Dan maar weer zijn bed uit! De hele nacht blijft hij doorgaan, waarbij brokken worden gemaakt en de taart verbrandt. Uitgeput valt hij ten slotte in slaap en wordt pas weer wakker als de feestgangers om zijn bed staan te zingen. Grappig, vlot leesbaar prentenboek met duidelijke tekst. De illustraties, in krijt stift en verf, zijn feestelijk gekleurd en in wisselende afmetingen. Ze zijn speels over de bladzijden verdeeld en sluiten naadloos aan op de situaties. Op elke pagina is een spinnetje verstopt en oplettende kleuters kunnen het tijdsverloop via tal van klokken volgen. Herkenbaar verhaal over de opwinding rondom een verjaardag. Vanaf ca. 4 jaar. Nelleke Hulscher-Meihuizen 2014-27-1933 Heruitgave Burton, Virginia Lee • Het huisje dat verhuisde *zie a.i.'s deze week voor nog vier prentenboeken uit de reeks 'Lemniscaat Het huisje dat verhuisde / Virginia Lee Burton ; vertaling [uit het Engels]: L.M. Niskos. Kroonjuweel'. - Vierde druk. - Rotterdam : Lemniscaat, 2014. - 44 ongenummerde pagina's : illustraties ; 24 × 26 cm. - (Lemniscaat Kroonjuweel). - Vertaling van: The little house. Niveau/leeftijd : AK - Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 1942. -

Juryrapport Griffels, Penselen, Paletten En Vlag En Wimpels 2016

Juryrapport Griffels, Penselen, Paletten en Vlag en Wimpels 2016 Juryrapport Griffels 2016 De Griffeljury 2016, bestaande uit: Margreet Ruardi (voorzitter), Martijn Blijleven, Adry Prade, Nathalie Scheffer en Nina Schouten, heeft de volgende boeken voorgedragen ter bekroning met een Zilveren Griffel of Vlag en Wimpel. De Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse Boek heeft deze voordracht overgenomen. Zilveren Griffels Tot zes jaar Tijs en de eenhoorn - Imme Dros Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Kom uit die kraan!! - Tjibbe Veldkamp Uitgeverij Lemniscaat Vanaf zes jaar Mooi boek - Joke van Leeuwen Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij De tuin van de walvis - Toon Tellegen Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Vanaf negen jaar Groter dan de lucht, erger dan de zon - Daan Remmerts de Vries Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Gips - Anna Woltz Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Informatief Een aap op de wc - Joukje Akveld Uitgeverij Hoogland & Van Klaveren Stem op de okapi - Edward van de Vendel Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Poëzie Nooit denk ik aan niets - Hans & Monique Hagen Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Rond vierkant vierkant rond - Ted van Lieshout Uitgeverij Leopold 3 Vlag en Wimpels Tot zes jaar Bas en Daan graven een gat - Mac Barnett Uitgeverij Hoogland & Van Klaveren Wat zou jij doen? - Guido van Genechten Clavis Uitgeverij Het boek zonder tekeningen - B.J. Novak Uitgeverij Lannoo Vanaf zes jaar Bens boot - Pieter Koolwijk Uitgeverij Lemniscaat De zee kwam door de brievenbus - Selma Noort Uitgeverij Leopold Lotte & Roos. Samen ben je niet alleen - Marieke Smithuis Em. Querido’s Kinderboeken Uitgeverij Vanaf negen jaar Spijkerzwijgen - Simon van der Geest Em. -

Talking Book Topics November-December 2016

Talking Book Topics November–December 2016 Volume 82, Number 6 About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics is published bimonthly in audio, large-print, and online formats and distributed at no cost to participants in the Library of Congress reading program for people who are blind or have a physical disability. An abridged version is distributed in braille. This periodical lists digital talking books and magazines available through a network of cooperating libraries and carries news of developments and activities in services to people who are blind, visually impaired, or cannot read standard print material because of an organic physical disability. The annotated list in this issue is limited to titles recently added to the national collection, which contains thousands of fiction and nonfiction titles, including bestsellers, classics, biographies, romance novels, mysteries, and how-to guides. Some books in Spanish are also available. To explore the wide range of books in the national collection, visit the NLS Union Catalog online at www.loc.gov/nls or contact your local cooperating library. Talking Book Topics is also available in large print from your local cooperating library and in downloadable audio files on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site at https://nlsbard.loc.gov. An abridged version is available to subscribers of Braille Book Review. Library of Congress, Washington 2016 Catalog Card Number 60-46157 ISSN 0039-9183 About BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download. To use BARD, contact your cooperating library or visit https://nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. -

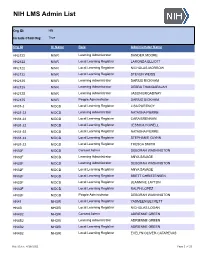

NIH LMS Admin List

NIH LMS Admin List Org ID: HN Include Child Org: True Org ID IC Name Role Administrator Name HN2122 NINR Learning Administrator SANDER MOORE HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar LARONDA ELLIOTT HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar NICHOLAS MORROW HN2122 NINR Local Learning Registrar STEVEN WEISS HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator DARIUS BICKHAM HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator DEBRA THANGARAJAH HN2125 NINR Learning Administrator JASON BROADWAY HN2125 NINR People Administrator DARIUS BICKHAM HN31-2 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar LISA PORTNOY HN31-22 NIDCD Learning Administrator NATASHA PIERRE HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar CARA BRENNAN HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar JESSICA HOWELL HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar NATASHA PIERRE HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar STEPHANIE GLYNN HN31-22 NIDCD Local Learning Registrar TRESCA SMITH HN32F NIDCD Content Admin DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN32F NIDCD Learning Administrator ANYA SAVAGE HN32F NIDCD Learning Administrator DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar ANYA SAVAGE HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar BRETT CHRISTENSEN HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar JEANNINE LAYTON HN32F NIDCD Local Learning Registrar RALPH LOPEZ HN32F NIDCD People Administrator DEBORAH WASHINGTON HN41 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar YASMEEN BECKETT HN4B NHGRI Local Learning Registrar NICHOLAS LOGAN HN4B2 NHGRI Content Admin ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Learning Administrator ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar ADRIENNE GREEN HN4B2 NHGRI Local Learning Registrar EVELYN -

Philip Gibbs EVENT-SYMMETRIC SPACE-TIME

Event-Symmetric Space-Time “The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” Muriel Rukeyser Philip Gibbs EVENT-SYMMETRIC SPACE-TIME WEBURBIA PUBLICATION Cyberspace First published in 1998 by Weburbia Press 27 Stanley Mead Bradley Stoke Bristol BS32 0EF [email protected] http://www.weburbia.com/press/ This address is supplied for legal reasons only. Please do not send book proposals as Weburbia does not have facilities for large scale publication. © 1998 Philip Gibbs [email protected] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Distributed by Weburbia Tel 01454 617659 Electronic copies of this book are available on the world wide web at http://www.weburbia.com/press/esst.htm Philip Gibbs’s right to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved, except that permission is given that this booklet may be reproduced by photocopy or electronic duplication by individuals for personal use only, or by libraries and educational establishments for non-profit purposes only. Mass distribution of copies in any form is prohibited except with the written permission of the author. Printed copies are printed and bound in Great Britain by Weburbia. Dedicated to Alice Contents THE STORYTELLER ................................................................................... 11 Between a story and the world ............................................................. 11 Dreams of Rationalism ....................................................................... -

United States District Court Southern District Of

Case 3:11-cv-01812-JM-JMA Document 31 Filed 02/20/13 Page 1 of 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 12 In re JIFFY LUBE ) Case No.: 3:11-MD-2261-JM (JMA) INTERNATIONAL, INC. TEXT ) 13 SPAM LITIGATION ) FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ) ACTION AND ORDER OF 14 ) DISMISSAL WITH PREJUDICE ) 15 16 Pending before the Court are Plaintiffs’ Motion for Final Approval of Class 17 Action Settlement (Dkt. 90) and Plaintiffs’ Motion for Approval of Attorneys’ Fees and 18 Expenses and Class Representative Incentive Awards (Dkt. 86) (collectively, the 19 “Motions”). The Court, having reviewed the papers filed in support of the Motions, 20 having heard argument of counsel, and finding good cause appearing therein, hereby 21 GRANTS Plaintiffs’ Motions and it is hereby ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and DECREED 22 THAT: 23 1. Terms and phrases in this Order shall have the same meaning as ascribed to 24 them in the Parties’ August 1, 2012 Class Action Settlement Agreement, as amended by 25 the First Amendment to Class Action Settlement Agreement as of September 28, 2012 26 (the “Settlement Agreement”). 27 2. This Court has jurisdiction over the subject matter of this action and over all 28 Parties to the Action, including all Settlement Class Members. 1 3:11-md-2261-JM (JMA) Case 3:11-cv-01812-JM-JMA Document 31 Filed 02/20/13 Page 2 of 10 1 3. On October 10, 2012, this Court granted Preliminary Approval of the 2 Settlement Agreement and preliminarily certified a settlement class consisting of: 3 4 All persons or entities in the United States and its Territories who in April 2011 were sent a text message from short codes 5 72345 or 41411 promoting Jiffy Lube containing language similar to the following: 6 7 JIFFY LUBE CUSTOMERS 1 TIME OFFER: REPLY Y TO JOIN OUR ECLUB FOR 45% OFF 8 A SIGNATURE SERVICE OIL CHANGE! STOP TO 9 UNSUB MSG&DATA RATES MAY APPLY T&C: JIFFYTOS.COM. -

What Happened Before the Big Bang?

Quarks and the Cosmos ICHEP Public Lecture II Seoul, Korea 10 July 2018 Michael S. Turner Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics University of Chicago 100 years of General Relativity 90 years of Big Bang 50 years of Hot Big Bang 40 years of Quarks & Cosmos deep connections between the very big & the very small 100 years of QM & atoms 50 years of the “Standard Model” The Universe is very big (billions and billions of everything) and often beyond the reach of our minds and instruments Big ideas and powerful instruments have enabled revolutionary progress a very big idea connections between quarks & the cosmos big telescopes on the ground Hawaii Chile and in space: Hubble, Spitzer, Chandra, and Fermi at the South Pole basics of our Universe • 100 billion galaxies • each lit with the light of 100 billion stars • carried away from each other by expanding space from a • big bang beginning 14 billion yrs ago Hubble (1925): nebulae are “island Universes” Universe comprised of billions of galaxies Hubble Deep Field: one ten millionth of the sky, 10,000 galaxies 100 billion galaxies in the observable Universe Universe is expanding and had a beginning … Hubble, 1929 Signature of big bang beginning Einstein: Big Bang = explosion of space with galaxies carried along The big questions circa 1978 just two numbers: H0 and q0 Allan Sandage, Hubble’s “student” H0: expansion rate (slope age) q0: deceleration (“droopiness” destiny) … tens of astronomers working (alone) to figure it all out Microwave echo of the big bang Hot MichaelBig S Turner Bang