11 Appendix.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha's Unique Theatre Form – Mughal Tamasha

Odisha Review JUNE - 2013 Odisha’s Unique Theatre Form – Mughal Tamasha Rabi Sankar Rath Rapid urbanization of the country accelerated by some near to extinction and some languishing and industrialization, globalization and development; breathing their last. It is therefore, necessary to ‘folk culture’ is no more cradled in the rustic do a comprehensive study of these performing hamlets of the country side. One does get to see art forms before they are extinct and people are some forms frequently manifested in city suburbs no longer able to relate to it, explain it, and largely because of a huge section of the rural understand it. Given institutional and social support audience has moved to the city in search of a new these forms can be revived, preserved and life and better livelihoods. While sophisticated TV fostered as unique art forms for both rural and and cinema is increasingly becoming common urban populace. recreation methods for these groups, they still yearn for familiar jatra, pala, daskathia or a The history of folk art in any country is theatre performance that takes them back to their obscure and therefore it is extremely difficult to roots – the rural, the rustic and the beauty and determine the exact time or period when they humility of it all. Therefore, in spite of the rapid came into existence. It is also because folk arts urbanization “folk art” still remains the art of are evolving in nature, continually adopt ‘people’ living both in urban and rural areas. themselves to changing times and needs and thus continue to lose a bit of their original form. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Veteran Leader Sharad Pawar to Inaugurate 31St Pune Festival on September 6Th

Press Release 31/ 08/2019 Veteran leader Sharad Pawar to Inaugurate 31st Pune Festival on September 6th Pune Festival a confluence of music, dance, drama, art, singing, instruments, sports and culture is celebrating its 31st year. It will be inaugurated at 4:30 pm on Friday, September 6th at Ganesh Kala Krida Ragmanch by veteran Leader Sharad Pawar. Tourism Minister of Maharashtra Jaykumar Rawal, Girish Bapat (MP), Amol Kolhe (MP), Ex Minister Harshwardhan Patil, Actress Urmila Matondkar, Managing Director of Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation Abhimanyu Kale, Pune’s Mayor Mukta Tilak, and Deputy Mayor Dr. Siddharth Dhende will be present as the guest of honour on the occasion. This year in Pune Festival there will be raft of diverse events. Danseuse actress Hema Malini's Ganga Ballet, All India Urdu Mushaira, Hindi humorous poetry convention, Marathi Hasya Kavi Sammelan, Mahila Mahotsav comprising Miss Pune Festival and Various competitions of dance, painting and cooking, Lavani for women, Keral Matosav, Kirtan Mahotsav, Uagawate Tare and Indradhanu, Marathi Drama, Musical Instrument, classical vocal and dances, Hindi Marathi songs program and various sports competitions will be the spectacular highlight of Pune Festival. Pune Festival’s patron, actress and danseuse Hema Malini presents her each ballet in Pune Festival. During the 30 years of the Pune Festival, she has presented her new ballet or Ganesh Vandana 27 times. This time, Hema Malini will present her ballet 'Ganga' at 8 pm on Sunday, September 8th. The Pune Festival is organized jointly by the Pune Festival Committee, Puneite citizens, Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation and Department of Tourism, Government of India. -

Folk Theatre Forms of India: Tamasha,Significance of Props

Folk Theatre Forms of India: Tamasha Tamasha is considered a major traditional dance form of the Marathi theatre, which includes celebration filled with dancing and singing and is performed mainly by nomadic theatre groups throughout the Maharashtra region. The word “Tamasha” is loaned from Persian, which in turn loaned it from Arabic, meaning a show or theatrical entertainment.1 In the Armenian language, “To do a Tamasha” means to follow an exciting and fun process or entertainment. Unofficially, this word has come to represent commotion or display full of excitement.1 The traditional form of Tamasha was inspired by a lot of other art forms like Kathakali, Kaveli, ghazals etc. The region of Maharashtra had a long theatrical tradition, with early references to the cave inscriptions at Nashik by Gautami Balashri, the mother of the 1st-century Satavahana ruler, Gautamiputras Satakarni. The inscription mentions him organizing Utsava’s a form of theatrical entertainment for his subjects.1 Tamasha acquired a distinct form in the late Peshwa period of the Maratha Empire and incorporated elements from older traditional forms like Dasavatar, Gondhal, Kirtan etc. Traditional Tamasha format consisted of dancing boys known as Nachya, who also played women’s roles, a poet-composer known as Shahir, who played the traditional role of Sutradhar, who compered the show. However, with time, women started taking part in Tamasha.2 Marathi theatre marked its journey at the beginning of 1843.3 In the following years, Tamasha primarily consisted of singing and dancing, expanded its range and added small dramatic skits known as Vag Natya.3 These included long narrative poems performed by the Shahir and his chorus, with actors improvising their lines. -

Conceptualising Popular Culture ‘Lavani’ and ‘Powada’ in Maharashtra

Special articles Conceptualising Popular Culture ‘Lavani’ and ‘Powada’ in Maharashtra The sphere of cultural studies, as it has developed in India, has viewed the ‘popular’ in terms of mass-mediated forms – cinema and art. Its relative silence on caste-based cultural forms or forms that contested caste is surprising, since several of these forms had contested the claims of national culture and national identity. While these caste-based cultural practices with their roots in the social and material conditions of the dalits and bahujans have long been marginalised by bourgeois forms of art and entertainment, the category of the popular lives on and continues to relate to everyday lives, struggles and labour of different classes, castes and gender. This paper looks at caste-based forms of cultural labour such as the lavani and the powada as grounds on which cultural and political struggles are worked out and argue that struggles over cultural meanings are inseparable from struggles of survival. SHARMILA REGE he present paper emerged as a part tested and if viewed as a struggle to under- crete issues of the 1970s; mainly the re- of two ongoing concerns; one of stand and intervene in the structures and sistance of British working class men and Tdocumenting the regional, caste- processes of active domination and sub- youth, later broadening to include women based forms of popular culture and the ordination, it has a potent potential for and ethnic minorities. By the 1980s cul- other of designing a politically engaged transformative pedagogies in regional tural studies had been exported to the US, course in cultural studies for postgraduate universities. -

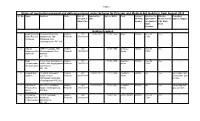

Status of Application Received and Deficiency Found Under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Onwards

1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 onwards Sr. No. Name Address Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o SO-Narsipatnam, 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Mdl-Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam - 531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Mdl- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Chandralapadu, Dist-Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Bandipalem- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Vill/Po, Mdl- Jaggayyapeta, Dist- Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Ambedkar Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Arilova, pension. Chinagadilimandal Dist- Visakhapatnam- 530 040. 2 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Madhura Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. Visakhapatnam- Narasimhulu 530 016. 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, 31/08/2018 1500/- J. Srinivasarao Dist-Krishna- 521 225 7 Tatineni Surya Near Mahalakshmi 549 15-06-2018 01-01-1944 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. -

Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University

Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University 1 JSPM’s JAYAWANTRAO SAWANT INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT & RESEARCH (NAAC Accredited, ISO certified, Approved by AICTE, Recognised by Govt. of Maharashtra and DTE and Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University) DTE Code: MB6143 Programme: Masters of Business Administration (M.B.A.) Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University JSPM’s JAYAWANTRAO SAWANT INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH (Near JSPM girls Hostel, Gate 2), Handewadi Road, , Hadapsar, Pune, Maharashtra, India www.jspmjsimr.edu.in 2 JSPM at Glance:- JSPM group of institutes has one of the best engineering colleges in Pune. Also, the group has MBA colleges, MCA colleges, Pharmacy colleges and PGDM courses one of the best in Pune and vicinity. JSPM provides right curriculum and innovative teaching methodologies to all its campuses. At JSPM there is a series of vibrant education and leadership strategies for gaining unbeatable competitive advantage from countrywide experts for a matchless growth beyond the ordinary. JSPM provides students a vibrant academic experience that adheres to stringent international quality standards, imbibes life skills among its students, and prepares them to not only take on competitive careers but also succeed in life. The underlying vision of the JSPM is to nurture and engender creativity in thought and innovation, thereby encouraging their students to follow an unconventional path. JSPM extra curriculum prepares dynamic students, personally and professionally, to take up future leadership roles in a global setting. JSPM is committed to high-quality education. The JSPM charter of higher learning clearly states: “Impart high- quality education which meets the diverse needs of our students and the evolving professional requirements”. -

Pension and Medical Aid (27-July 2019).Pdf

Page 1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Sr. No. Name Address State Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, SO- Andhra 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o Narsipatnam, Mdl- Pradesh 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam -531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, Mdl- Andhra 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Chandralapadu, Dist- Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near Bandipalem- Andhra 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Vill/Po, Mdl-Jaggayyapeta, Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Dist-Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, Ambedkar Andhra 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Nagar, Arilova, Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Chinagadilimandal Dist- pension. Visakhapatnam-530 040. 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, Madhura Andhra 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Nagar, Visakhapatnam- Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. 530 016. Narasimhulu 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, Andhra 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, Pradesh 31/08/2018 1500/- J. -

About Satara

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

Revitalizing Mumbai Textile Mill Lands for the City Vinay Surve University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Revitalizing Mumbai Textile Mill Lands for the City Vinay Surve University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons, Interior Architecture Commons, Landscape Architecture Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Surve, Vinay, "Revitalizing Mumbai Textile Mill Lands for the City" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 722. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/722 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revitalizing Mumbai textile mill lands for the city A Dissertation Presented by VINAY ARUN SURVE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE September 2011 Architecture + Design Program Department of Art, Architecture and Art History Revitalizing Mumbai textile mill lands for the city A Dissertation Presented by VINAY ARUN SURVE Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Kathleen Lugosch, Chair _______________________________________ Max Page, Member _______________________________________ Alexander C. Schreyer, Member ____________________________________ William T. Oedel, Chair, Department of Art, Architecture and Art History DEDICATION For my beloved Aai (mother), Bhau (Father), Manish (Brother), Tejas (Brother), Bhakti (Sister in law), and Tunnu (Nephew). And Professor David Dillon ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to start by thanking the institution, UMASS Amherst for providing every support system in achieving this milestone. -

International Conference on Maharashtra

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MAHARASHTRA 21 – 25 SEPTEMBER 2021, OXFORD Platform: Zoom All timings below are British Summer Time (GMT + 1) Tuesday 21st September 12.30pm – Welcome Note – Polly O’Hanlon and Shailen Bhandare (with Shraddha Kumbhojkar, Anjali Nerlekar and Aruna Pendse) 1pm - 3 pm 1. Circulation: Journeys and identities Chair: Anne Feldhaus Narayan Bhosle and Vandana Sonalkar (University of Mumbai / TISS, Mumbai) – From Circulation to Settlement: Nomadic Tribes in Transition Shreeyash Palshikar (Philadelphia, USA) - Wandering Wonderworkers: Circulations of Madaris in Maharashtra, Maratha period to the present Madhuri Deshmukh (Oakton Community College, Des Plaines, USA) - Vanvās to Vārī: The Travel History of Songs and Poetry in Maharashtra Mario da Penha (Rutgers University, New Jersey, USA) - Beggars On the Move: Hijra Journeys in the Eighteenth-century Deccan 3.30 – 5.30 pm 2. Circulation, Literature and the Early Modern Public Sphere Chair: Ananya Vajpeyi Sachin Ketkar (MS University, Vadodara) - Travelling Santas, Circulation and Formation of ‘the Multilingual Local’ of World Literature in the early modern Marathi Prachi Deshpande (CSSS, Kolkata) - Writing and Circulation: A Material Approach to Early Modern Marathi Literature Roy Fischel (SOAS, UK) - Circulation, Patronage, and Silence in the Practice of History Writing in Early Modern Maharashtra Wednesday 22nd September 10.30 am -12.30 pm 3. Marathi Abroad Chair: Shailen Bhandare Anagha Bhatt-Behere (SPPU, Pune) - From Russia to Bombay, from Bombay to Soviet Union and Back: The journey of Annabhau Sathe’s Maza Russia cha Pravas Aditya Panse (Independent scholar, London, UK) - 配य車नी पयहिलेली हिलययत: मरयठी प्रियशय車नी १८६७ ते १९४७ यय कयळयत हलहिलेल्यय इ車ग्ल車डच्यय प्रियसिर्णनय車चय सयमयहिक अभ्ययस 4.