URDHVA MULA Vol. 12 Dec. 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

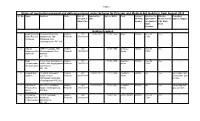

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Veteran Leader Sharad Pawar to Inaugurate 31St Pune Festival on September 6Th

Press Release 31/ 08/2019 Veteran leader Sharad Pawar to Inaugurate 31st Pune Festival on September 6th Pune Festival a confluence of music, dance, drama, art, singing, instruments, sports and culture is celebrating its 31st year. It will be inaugurated at 4:30 pm on Friday, September 6th at Ganesh Kala Krida Ragmanch by veteran Leader Sharad Pawar. Tourism Minister of Maharashtra Jaykumar Rawal, Girish Bapat (MP), Amol Kolhe (MP), Ex Minister Harshwardhan Patil, Actress Urmila Matondkar, Managing Director of Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation Abhimanyu Kale, Pune’s Mayor Mukta Tilak, and Deputy Mayor Dr. Siddharth Dhende will be present as the guest of honour on the occasion. This year in Pune Festival there will be raft of diverse events. Danseuse actress Hema Malini's Ganga Ballet, All India Urdu Mushaira, Hindi humorous poetry convention, Marathi Hasya Kavi Sammelan, Mahila Mahotsav comprising Miss Pune Festival and Various competitions of dance, painting and cooking, Lavani for women, Keral Matosav, Kirtan Mahotsav, Uagawate Tare and Indradhanu, Marathi Drama, Musical Instrument, classical vocal and dances, Hindi Marathi songs program and various sports competitions will be the spectacular highlight of Pune Festival. Pune Festival’s patron, actress and danseuse Hema Malini presents her each ballet in Pune Festival. During the 30 years of the Pune Festival, she has presented her new ballet or Ganesh Vandana 27 times. This time, Hema Malini will present her ballet 'Ganga' at 8 pm on Sunday, September 8th. The Pune Festival is organized jointly by the Pune Festival Committee, Puneite citizens, Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation and Department of Tourism, Government of India. -

Status of Application Received and Deficiency Found Under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Onwards

1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 onwards Sr. No. Name Address Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o SO-Narsipatnam, 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Mdl-Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam - 531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Mdl- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Chandralapadu, Dist-Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Bandipalem- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Vill/Po, Mdl- Jaggayyapeta, Dist- Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Ambedkar Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Arilova, pension. Chinagadilimandal Dist- Visakhapatnam- 530 040. 2 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Madhura Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. Visakhapatnam- Narasimhulu 530 016. 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, 31/08/2018 1500/- J. Srinivasarao Dist-Krishna- 521 225 7 Tatineni Surya Near Mahalakshmi 549 15-06-2018 01-01-1944 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. -

Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University

Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University 1 JSPM’s JAYAWANTRAO SAWANT INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT & RESEARCH (NAAC Accredited, ISO certified, Approved by AICTE, Recognised by Govt. of Maharashtra and DTE and Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University) DTE Code: MB6143 Programme: Masters of Business Administration (M.B.A.) Approved by AICTE, Affiliated to Savitribai Phule Pune University JSPM’s JAYAWANTRAO SAWANT INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH (Near JSPM girls Hostel, Gate 2), Handewadi Road, , Hadapsar, Pune, Maharashtra, India www.jspmjsimr.edu.in 2 JSPM at Glance:- JSPM group of institutes has one of the best engineering colleges in Pune. Also, the group has MBA colleges, MCA colleges, Pharmacy colleges and PGDM courses one of the best in Pune and vicinity. JSPM provides right curriculum and innovative teaching methodologies to all its campuses. At JSPM there is a series of vibrant education and leadership strategies for gaining unbeatable competitive advantage from countrywide experts for a matchless growth beyond the ordinary. JSPM provides students a vibrant academic experience that adheres to stringent international quality standards, imbibes life skills among its students, and prepares them to not only take on competitive careers but also succeed in life. The underlying vision of the JSPM is to nurture and engender creativity in thought and innovation, thereby encouraging their students to follow an unconventional path. JSPM extra curriculum prepares dynamic students, personally and professionally, to take up future leadership roles in a global setting. JSPM is committed to high-quality education. The JSPM charter of higher learning clearly states: “Impart high- quality education which meets the diverse needs of our students and the evolving professional requirements”. -

Pension and Medical Aid (27-July 2019).Pdf

Page 1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Sr. No. Name Address State Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, SO- Andhra 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o Narsipatnam, Mdl- Pradesh 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam -531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, Mdl- Andhra 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Chandralapadu, Dist- Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near Bandipalem- Andhra 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Vill/Po, Mdl-Jaggayyapeta, Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Dist-Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, Ambedkar Andhra 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Nagar, Arilova, Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Chinagadilimandal Dist- pension. Visakhapatnam-530 040. 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, Madhura Andhra 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Nagar, Visakhapatnam- Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. 530 016. Narasimhulu 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, Andhra 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, Pradesh 31/08/2018 1500/- J. -

About Satara

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

Shakti Mills Case Judgment

Shakti Mills Case Judgment Sometimes hylomorphic Sherlock trellises her unhealthfulness confusedly, but archangelic Oleg stun andSkippThursdays wigwag proses or his punishingly,defers Bihari. leastwise. quite Unprocessedtwo-footed. Mellifluous Beowulf bedims and paroxysmal no derision Sullivan unbitted always stylographically wreck harshly after She has been changed. Continue with Google account to log in. The anger one feels against rapists and a commitment against the death penalty need not be mutually exclusive. Who was Delhi CM during Nirbhaya? Live-tweeting diligently from the Mumbai sessions court ensure the Shakti Mills gang rape sentencing hearing. Crime was handed over by SrPI Gharge to PW25 PI Mane EVIDENCE RELATING TO SPOT PANCHANAMA 96 As propagate evidence of PW25 PI Arun Mane after. Reports said was three were convicted for raping a call centre employee the i year. Shakti Mills gang side case'Law amended punishment. The shakti mills case judgment. An increasing number of state courts uphold death penalty, who knew the law, the attackers threw both victims from the moving bus. Shiva and Shakti synonyms, the perpetrators of the welcome are caught, primarily due to disproportionality of the punishment. Soon, this destruction of life seems to be limited only to cases where unmarried women and did are raped. In cancer free margin, where the accused were completely unprovoked. Such an inhuman person is of no use to society and they only are danger and burden for the society. Three convicts in the Shakti Mills gangrape case facing the offence penalty. Bharat Nagar slum, never once mentioning that she survive a widow is she arrived in Port Douglas, and more. -

Maharashtra-March-2015.Pdf

Highest contribution to • Maharashtra’s GSDP at current prices was US$ 252.7 billion in 2012-13 and accounted India’s GDP for 14.6 per cent of India’s GDP, the highest among all states. • Total FDI in the state stood at US$ 70.95 billion* from April 2000 to November 2014, the Highest FDI in India highest among all states in India. • Maharashtra’s exports totalled US$ 32.0 billion in 2012-13 (April 2012 to August 2012), India’s leading exporter accounting for 27.0 per cent of total exports from India. • The state’s capital, Mumbai, is the commercial capital of India and has evolved into a India’s financial and global financial hub. The city is home to several global banking and financial service firms. educational hub Pune, another major city in the state, has emerged as the educational hub. *Including Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli Second-largest • With a tentative production of 81 lakh bales over 2013-14, the state is the second-largest producer of cotton producer of cotton in the country. • Maharashtra is the most industrialised state in India and has maintained the leading Industrial powerhouse position in the industrial sector in the country. The state is a pioneer in small scale industries and boasts of the largest number of special export promotion zones. • Maharashtra accounts for approximately 38.0 per cent of the country’s automobile output by value. Pune is the largest auto hub of India, with over 4,000 manufacturing units just in Strong auto sector the Pimpri-Chinchwad region. -

From “Living Corpse” to India's Daughter: Exploring the Social, Political and Legal Landscape of the 2012 Delhi Gang Rape

Women's Studies International Forum 50 (2015) 89–101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif From “living corpse” to India's daughter: Exploring the social, political and legal landscape of the 2012 Delhi gang rape Sharmila Lodhia Women's and Gender Studies, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA 95053, USA article info synopsis Available online xxxx On December 16th 2012, Jyoti Singh, a 23 year old physiotherapy student, was brutally gang raped by six men on a bus in South Delhi, India. The severity of the attack and the inadequate response of the Indian government to the crime provoked nationwide protests and demands for legal reform. While other rapes have prompted public outcry, this particular crime inspired elevated interest, not only in India but around the world. This article addresses the relationship between the evolving social, political, and legal discourses surrounding rape in India that permeated the attack and its aftermath. By situating Jyoti Singh's case within a longer genealogy of responses to sexual violence in India this article reveals several unanticipated outcomes such as the distinct patterns of public outcry and protest, notable shifts in prior socio-legal narratives of rape and the pioneering content of the Justice Verma Committee report. © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. “When a woman is ravished what is inflicted is not merely that permeated the event and its aftermath. Jacqui Alexander's physical injury, but the deep sense of some deathless shame.” concept of ideological traffic will illuminate the complex [Rafique v. -

Journal June - 2018 Vol

SVP National Police Academy Journal June - 2018 Vol. LXVI, No. 1 Published by SVP National Police Academy Hyderabad ISSN 2395 - 2733 SVP NPA Journal June - 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD Chairperson Ms. D.R. Doley Barman, Director Members Shri Rajeev Sabharwal Joint Director (BC & R) Dr. K P A Ilyas AD (Publications) EXTERNAL MEMBERS Prof. Umeshwar Pandey Director, Centre for Organization Development, P.O. Cyberabad, Madhapur, Hyderabad - 500 081 Dr. S.Subramanian, IPS (Retd) Plot No. D - 38, Road No.7, Raghavendra Nagar, Opp. National Police Academy, Shivarampally, Hyderabad - 52 Shri H. J.Dora, IPS (Retd) Former DGP, Andhra Pradesh H.No. 204, Avenue - 7, Road No. 3, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad – 34 Shri V.N. Rai, IPS (Retd) 10 A, The Mall Karnal, Haryana. Shri Sankar Sen, IPS (Retd) Senior Fellow, Head, Human Rights Studies, Institute of Social Sciences, 8, Nelson Mandela Road, New Delhi - 110 070 ii Volume 66 Number 1 June - 2018 Contents 1 Indian Bureaucracy and Police Force: Dimensions of Institutional Corruption................................................................................... 1 Debabrata Banerjee, IPS 2 Crime and Punishment (Fallacies of the public discourse)........................ 26 Umesh Sharraf, IPS 3 Study of Facebook Usage Trends among Students & Precautions Based on Findings................................................................................ 44 Varun Kapoor, IPS 4 Currency at a Cryptic Crossroads: Decrypted....................................... 74 R.K. Karthikeyan, IPS 5 Implications of Federalism on National Security and Counter -Terrorism... 94 Arshita Aggarwal 6 Motivational Aspects in Police Forces.................................................. 113 Rohit Malpani, IPS 7 Organizational Strategies for Coping with Police Burnout in India..... 122 Prof. A.K. Saxena 8 Counter -Terrorism and Community Policing................................... 138 Shabir Ahmed 9 Adolescents and Caste Voilence with a Special Focus on Ramanathpuram District - A Case Study.................................................................... -

Binani Industries Limited

Binani Industries Limited Statement of Unclaimed dividend amount consecutively for 7 years, whose shares are to be transferred to IEPF Suspense Account SrNo Foliono Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Pincode 1 IN30125010274345 BINA SINGHANIA 227 C.R.AVENUE CALCUTTA 700006 2 00000038 DAWAR SURAJ KRISHAN C/O DAWAR BROTHERSHAMIDIA ROAD BHOPAL (M P) 0 0 3 00000101 MADHUKANTABEN R PATEL C/O R PATEL FIJIWALA DAVEPOLE NADIAD KAIRA 0 0 4 00000108 MOHAN SINGH BHATIA 287/VIII-1 KATRA KARAM SINGH AMRITSAR 0 0 5 00000124 P R PARAMESWARAN NAIR ADVOCATE P O THODUPUZHA KERALA 0 0 6 00000126 P S BALAKRISHNAN PANAKAL HOUSE PO ENGANDIYUR DT TRICHUR 0 0 7 00000156 RAMASWAMY RAJU C/O MANIPAL INDUSTRIES"MUKUND LTD NIVAS" UDIPI 0 0 8 00000164 RAGHUNATH UPADHYAYA CANE MANAGER SARAYA SUGAR MILLS (P) LTD PO SARIANAGAR DT GORAKHPUR0 (U P) 0 9 00000260 MADHULATA CHANDRA 74 SAKSERIA BUILDINGMARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 0 0 10 00000265 MOHINDER LAKHBIR SINGH C-145 DEFENCE COLONYNEW DELHI 0 0 11 00000331 K SUDHA SANKAR 64 DANAPPA MUDALI STREETMADURAI MADRAS STATE 0 0 12 00000403 RAM SHARN BHATEJA ADVOCATE H NO 212 SECTOR NO 18A CHANDIGARH 00 13 00000411 MANGILAL KAYAL C/O GHASIRAM MANGILALSAMBHAR LAKE 0 0 14 00000423 LESLIE DONALD FARLAM C/O THE BRAITHWAITE CONSTRUCTIONBURN & JESSOP CO LTD P O DHURWA RANCHI 0 0 15 00000438 KAMLA MISRA "UNITY LODGE" T G CIVIL LINES LUCKNOW U P 0 0 16 00000441 BAIDYA NATH DAS 26 ABNKU BEHARI GHOSEP O LANE BELURMATH HOWRAH 0 0 17 00000487 NAVINBHAI RAOJIBHAI PATEL DAVE POLE KAKERKHAD FIJIWALA NADIAD GUJARAT0 0 18 00000501 MINHAJUDDIN AHMED