San Juan River Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

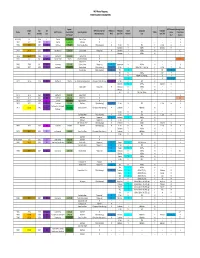

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS Approx. ADOT Named or Average Annual Length Year Age OAW/Impaired/ Not‐ Within 1/4 Pollutants ADOT Designated Pollutants Route ADOT Districts Annual Traffic Receiving Waters TMDL? Given Precipitation (mi) Installed (yrs) Attaining Waters? Mile? (per EPA) Pollutant? Uses (per EPA) (Vehicles/yr) WLA? (inches) SR 24 (802) 1.0 2014 5 Central 11,513,195 Queen Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 51 16.7 1987 32 Central 61,081,655 Salt River N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 61 76.51 1935 84 Northeast 775,260 Little Colorado River Y (Not attaining) N E. Coli N FBC Y E. Coli N 7 Sediment Y A&Wc Y Sediment N SR 64 108.31 1932 87 Northcentral 2,938,250 Colorado River Y (Impaired) N Sediment Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ 8.5 Selenium Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 66 66.59 1984 35 Northwest 5,154,530 Truxton Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 7 SR 67 43.4 1941 78 Northcentral 39,055 House Rock Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 17 Kanab Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 68 27.88 1941 78 Northwest 5,557,490 Colorado River Y (Impaired) Y Temperature N A&Ww N ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 69 33.87 1938 81 Northwest 17,037,470 Granite Creek Y (Not attaining) Y E. Coli N A&Wc, FBC, FC, AgI, AgL Y E. Coli Y 9.5 Watson Lake Y (Not attaining) Y TN Y ‐‐ Y TN Y DO N A&Ww Y DO Y pH N A&Ww, FBC, AgI, AgL Y pH Y TP Y ‐‐ Y TP Y SR 71 24.16 1936 83 Northwest 296,015 Sols Wash/Hassayampa River Y (Impaired, Not attaining) Y E. -

Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. July 22, 2021 Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015 Effective March 17, 2021 The federal Clean Water Act (CWA) requires states and federally recognized Indian tribes to adopt water quality standards in order to "restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's Waters" (CWA, 1988). The attached WQS document is in effect for Clean Water Act purposes with the exception of the following provisions. Navajo Nation’s previously approved criteria for these provisions remain the applicable for CWA purposes. The “Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2015” (NNSWQS 2015) made changes amendments to the “Navajo Nation Surface Water Quality Standards 2007” (NNSWQS 2007). For federal Clean Water Act permitting purposes, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) must approve these changes to the NNSWQS 2007 which are found in the NNSWQS 2015. The USEPA did not approve of three specific changes which were made to the NNSWQS 2007 and are in the NNSWQS 2015. (October 15, 2020 Letter from USEPA to Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency). The three specific changes which USEPA did not accept are: 1) Aquatic and Wildlife Habitat Designated Use - Suspended Solids Changes (NNSWQS 2015 Section 207.E) The suspended soils standard for aquatic and wildlife habitat designated use was changed to only apply to flowing (lotic) surface waters and not to non-flowing (lentic) surface waters. -

ARIZONA WATER ATLAS Volume 1 Executive Summary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Arizona Department of Water Resources September 2010 ARIZONA WATER ATLAS Volume 1 Executive Summary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Director, Arizona Department of Water Resources Herbert Guenther Deputy Director, Arizona Department of Water Resources Karen Smith Assistant Director, Hydrology Frank Corkhill Assistant Director, Water Management Sandra Fabritz-Whitney Atlas Team (Current and Former ADWR staff) Linda Stitzer, Rich Burtell – Project Managers Kelly Mott Lacroix - Asst. Project Manager Phyllis Andrews Carol Birks Joe Stuart Major Contributors (Current and Former ADWR staff) Tom Carr John Fortune Leslie Graser William H. Remick Saeid Tadayon-USGS Other Contributors (Current and Former ADWR staff) Matt Beversdorf Patrick Brand Roberto Chavez Jenna Gillis Laura Grignano (Volume 8) Sharon Morris Pam Nagel (Volume 8) Mark Preszler Kenneth Seasholes (Volume 8) Jeff Tannler (Volume 8) Larri Tearman Dianne Yunker Climate Gregg Garfin - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Ben Crawford - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Casey Thornbrugh - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Michael Crimmins – Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science, University of Arizona The Atlas is wide in scope and it is not possible to mention all those who helped at some time in its production, both inside and outside the Department. Our sincere thanks to those who willingly provided data and information, editorial review, production support and other help during this multi-year project. Arizona Water Atlas Volume 1 CONTENTS SECTION 1.0 Atlas Purpose and Scope 1 SECTION 1.1 Atlas -

Flood Hydroclimatology and Extreme Events in the Southwest: a Streamflow Perspective

Flood Hydroclimatology and Extreme Events in the Southwest: A Streamflow Perspective Katherine Hirschboeck* Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research SW Extreme Precipitation Symposium Hydrology & Atmospheric Sciences 27 March 2019 The University of Arizona * With Diana Zamora-Reyes & Saeahm Kim Overview • Prologue • “Flood Hydroclimatology” Revisited • Flood Heterogeneity & the Complexities of Predictability • “Catastrophic Flooding” Revisited • Postscripts: On Tree-Rings, Floods • & the Future PROLOGUE UPPER MIDWEST FLOODING “The persistence of March 2019 climatic departures implies that the assumption of randomness-over-time, which is basic to most Source: New York Times 3/21/2019 techniques currently employed by federal and state agencies . 1975 is frequently not valid.” Knox et al. 1975 Newspaper advertisement . THE FLOOD PROCESSOR Expanded feed tube – Combines floods of different types together Chopping, slicing & grating blades – Chops up climatic cause information and slices off extreme high outliers Plastic mixing blade – Mixes up unique statistical properties of individual floods FLOOD HYDROCLIMATOLOGY . is the analysis of flood events within the context of their history of variation . - in magnitude, frequency, seasonality - over a relatively long period of time - analyzed within the spatial framework of changing combinations of meteorological causative mechanisms Hirschboeck, 1988 Generalized Seasonality of Peak Flooding in the Southwest Hirschboeck, 1991 after figure in USGS Ground Water manual FLOOD HYDROCLIMATOLOGY FLOOD-CAUSING -

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Description Job Number Date Thompson Lawn 1350 1946 August Peter Thatcher 1467 undated Villa Moderne, Taylor and Vial - Carmel 1645-1951 1948 Telephone Building 1843 1949 Abrego House 1866 undated Abrasive Tools - Bob Gilmore 2014, 2015 1950 Inn at Del Monte, J.C. Warnecke. Mark Thomas 2579 1955 Adachi Florists 2834 1957 Becks - interiors 2874 1961 Nicholas Ten Broek 2878 1961 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1517 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1581 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1873 circa 1945-1960 Portraits unnumbered circa 1945-1960 [Naval Radio Training School, Monterey] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 [Men in Hardhats - Sign reads, "Hitler Asked for It! Free Labor is Building the Reply"] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 CZ [Crown Zellerbach] Building - Sonoma 81510 1959 May C.Z. - SOM 81552 1959 September C.Z. - SOM 81561 1959 September Crown Zellerbach Bldg. 81680 1960 California and Chicago: landscapes and urban scenes unnumbered circa 1945-1960 Spain 85343 1957-1958 Fleurville, France 85344 1957 Berardi fountain & water clock, Rome 85347 1980 Conciliazione fountain, Rome 84154 1980 Ferraioli fountain, Rome 84158 1980 La Galea fountain, in Vatican, Rome 84160 1980 Leone de Vaticano fountain (RR station), Rome 84163 1980 Mascherone in Vaticano fountain, Rome 84167 1980 Pantheon fountain, Rome 84179 1980 1 UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Quatre Fountain, Rome 84186 1980 Torlonai -

THE SAN JUAN CANYON H PUBLIC

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 538 THE SAN JUAN CANYON SOUTHEASTERN UTAH A GEOGRAPHIC AND HYDROGRAPHIC RECONNAISSANCE BY HUGH D. MISER h PUBLIC WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1924 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FKOM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 30 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS Page Location-_________________________________ 1 Present and previous explorations________,________ 1 Acknowledgments ________________________________ 4 Suggestions to overland travelers____________________ 4 Geography _ _____ _ _______ _ _ _ 6 Surface features _________________________,____ & Bluff to Chinle Creek______________________ _ 7 Chinle Creek to Cedar Point__________________-_ 8 Cedar Point to Clay Hill Crossing__________________ 9 Clay Hill Crossing to Piute Farms__________________ 11 Piute Farms to mouth of river____________ _ _ __ 11 Climate____________________________________ 16 Precipitation and temperature___________________ 16 Wind_*._______________________________1_ 17 Soil_______________________________________ 18 Flora_______________________________________ 18 Animals __________________________________ 20 Mineral resources ______________________________ 21 Inhabitants_______________________________j._ 22 Irrigation and agriculture_________________________ 24 Archeology. ___________________________________ 25 Roads and trails ______________________________ 26 Geology_______________________________________ -

River Flowing from the Sunrise: an Environmental History of the Lower San Juan

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Recommended Citation Aton, James M. and McPherson, Robert S., "River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan" (2000). All USU Press Publications. 128. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/128 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan A. R. Raplee’s camp on the San Juan in 1893 and 1894. (Charles Goodman photo, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library, University of Utah) River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press all rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Manfactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 654321 000102030405 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aton, James M., 1949– River flowing from the sunrise : an environmental history of the lower San Juan / James M. Aton, Robert S. McPherson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-404-1 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87421-403-3 (pbk. -

Drought Conditions in Utah During 1999-2002: a Historical Perspective

Drought Conditions in Utah During 1999-2002: A Historical Perspective Soda Springs Introduction 2001, to September 30, 2002): Colorado River Smiths Fork near RiverBear near Cisco, San Juan River near Bluff, and 114° IDAHO Lake Border, Wyoming ° 42° 109 Bear Green Virgin River at Virgin. At two other gages in “When the well is dry, we learn River WYOMING River Logan eastern Utah, Whiterocks River near Whiterocks the worth of water” - Ben Franklin, Bear Green River Evanston Ogden Flaming and Green River near Green River, 2002 was from Poor Richard’s Almanac, 1733 Web Gorge er R Reservoir Great Fork the second driest year on record. Streamflow iv Blacks Salt e r Lake Weber River near Oakley Jordan Salt in the Upper Colorado River Basin has been so River Utah’s weather is prone to extremes—from Lake D City u c h low that the water surface of Lake Powell is severe flooding to multiyear droughts. Five es neR Provo iv Whiterockse River White COLORADO predicted to be 80 feet below the fill level by Utah r major floods occurred during 1952, 1965, 1966, near Whiterocks Lake River r e January 2003 (Bureau of Reclamation, 2002). v 1983, and 1984, and six multiyear droughts i R P n The water level of Lake Powell is currently e NEVADA r occurred during 1896-1905, 1930-36, 1953-65, i e ce r R G iv (2003) low enough near Hite Marina (at the 1974-78 (U.S. Geological Survey, 1991), and UTAH er M u Green River upstream end of the lake) that much of the d more recently during 1988-93 and 1999-2002. -

Appendix III

Appendix III Moments for each flood producing mechanism Annual Maximum Series Flood Frequency Moments for Tropical Cyclone Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Moments for Convective Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Moments for Synoptic Annual Maximum Series. N is the number of years with data on record. Flood Frequency Curves: Bulletin 17B Maximum ONLY 09379200 Chinle Creek near Mexican Water 09382000 Paria River near Lees Ferry 09384000 Little Colorado River above Lyman Lake near St. John’s 09393500 Silver Creek near Snowflake 09402000 Little Colorado River near Cameron 09424450 Big Sandy River near Wikieup 09424900 Santa Maria River near Bagdad 09426000 Bill Williams River below Alamo Dam 09432000 Gila River below Blue Creek, NM 09447000 Eagle Creek near Pumping Plant near Morenci 09448500 Gila River at Head of Safford Valley near Solomon 09468500 San Carlos River near Peridot 09471000 San Pedro River near Charleston 09473000 Aravaipa Creek near Mammoth 09480000 Santa Cruz River near Lochiel 09480500 Santa Cruz River near Nogales 09482500 Santa Cruz River near Tucson 09490500 Black River near Fort Apache 09492400 East Fork White River near Fort Apache 09497980 Cherry Creek near Globe 09499000 Tonto Creek above Gun Creek near Roosevelt 09504000 Verde River near Clarkdale 09504500 Oak Creek near Cornville 09505800 West Clear Creek near Camp Verde 09508500 Verde River below Tangle Creek above Horseshoe Dam 09510200 Sycamore Creek near Ft -

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021

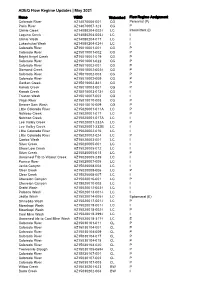

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021 Name WBID Watershed Flow Regime Assignment Colorado River AZ14070006-001 CG Perennial (P) Paria River AZ14070007-123 CG P Chinle Creek AZ14080204-002-I LC Intermittent (I) Laguna Creek AZ14080204-003-I LC I Chinle Wash AZ14080204-017 LC I Lukachukai Wash AZ14080204-024-I LC I Colorado River AZ15010001-001 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-002 CG P Bright Angel Creek AZ15010001-019 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-022 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-001 CG P Diamond Creek AZ15010002-002-I CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-003 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-009 CG P Garden Creek AZ15010002-841 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-001 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-013-I CG I Truxton Wash AZ15010007-002 CG I Virgin River AZ15010010-003 CG P Beaver Dam Wash AZ15010010-009 CG P Little Colorado River AZ15020001-011A LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017 LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017A LC I Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232A LC P Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232B LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-016 LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-024 LC P Carrizo Wash AZ15020003-001 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-001 LC I Show Low Creek AZ15020005-012 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-013 LC P Unnamed Trib to Walnut Creek AZ15020005-239 LC I Puerco River AZ15020007-005 LC I Jacks Canyon AZ15020008-004 LC I Clear Creek AZ15020008-006 LC P Clear Creek AZ15020008-007 LC I Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-001 LC P Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-003 LC I Oraibi Wash AZ15020012-003-I LC I Polacca Wash AZ15020013-001-I LC I Jadito Wash AZ15020014-005-I LC Ephemeral -

Circuit USA : Au Pays Des Westerns

Ecran-Plus - Circuit USA : Au pays des Westerns Un parcours qui vous mènera dans l'ouest du Texas, à l'ouest du Pecos, le long du Rio Grande. Vous remonterez ensuite au Nouveau Mexique sur la trace des Améridiens, jusqu'au Colorado, Pour terminer par les sites grandioses de l'Utah, et de l'Arizona si vous optez pour les versions les plus longues de ce parcours. Ce parcours conviendra plus particulièrement à ceux qui ont dejà eu un premier contact avec les Etats Unis, et l'Ouest en particulier, et souhaitent découvrir des lieux plus retirés en faisant des randonnées sur des pistes, que ce soit en 4x4 ou à pieds, sur des parcours parfois de plusieurs jours. Vous parcourerez tous les grands sites de la conquêtes de l'ouest, depuis les grandes plaines du Texas, vous franchirez le Pecos et entrerez dans les territoires de l'ouest sauvage, le wide wild west, vous suivrez le Rio Grande, avant de vous diriger vers les montagnes en passant par Santa Fe, vous traverserez les paysages inoubliables des grands westerns, déserts parsemés de grandioses falaises, vous vivrez l'aventures des pistes, vous admirerez les merveilles des canyons tout au long du Colorado, vous vivrez la démesure de Las Vegas et roulerez sur la mythique route 66. Un parcours de 6 à 8 semaines ou plus à travers l'ouest américain. Le circuit est largement modulable, à partir de la troisième semaine, en fonction de ce que vous pourriez avoir déjà visité dans d'autres parcours ou de votre volonté ou non de faire des excursion en 4x4 sur les pistes de l'Utah.