Julia Wachtel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PETER HALLEY Biografía

BARCELONA GALLERY WEEKEND 2020 galeria SENDA PETER HALLEY Biografía Peter Halley (Nueva York, 1953) se dio a conocer a mediados de los años ochenta en Nueva York como impulsor del Neo-conceptualismo, corriente que aparece como reacción al neoim- presionismo y que supone un resurgimiento de la abstracción geométrica. Su estilo refleja la idea del lenguaje como sistema estable y autorreferencial, y critica las reivindicaciones tras- cendentales del minimalismo. Además, su obra presenta una influencia por la teoría social del Estructuralismo, la cual plantea el análisis de los sistemas socioculturales y de los lenguajes, a partir de configuraciones y estructuras simbólicas profundas, que condicionan y determinan todo lo que ocurre en la actividad humana. Así pues, las celdas y los conductos que Peter Ha- lley articula y combina en sus lienzos, no son una simple composición geométrica abstracta, sino más bien una imagen simbólica de los esquemas sociales que nos rodean. “En nuestra cultura, la geometría se suele considerar un signo de lo racional. Yo, por algún motivo, considero que es al revés, que la geometría posee una significación primaria, más psi- cológica que intelectual”, afirma en su ensayo “La Geometría y lo Social” de 1991. Peter Halley ha sido director de estudios de pintura de la Universidad de Yale y ha impartido clases en la Universidad de Columbia, en UCLA y en la Escuela de Artes Visuales de Nueva York. De 1996 a 2005 fue editor de la revista cultural Index Magazine. Ha realizado exposicio- nes individuales en la Academia de Arte de la Bienal de Venecia, en el contexto de la Bienal de Venecia de 2019, el MoMA de Nueva York en 1997 y el Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía de Madrid en 1992. -

LA Marque Noire

PALAIS DE TOKYO / PRESS KIT / LA MARQUE NOIRE / LA MARQUE NOIRE / STEVEN PARRINO RETROSPECTIVE, PROSPECTIVE MAY 24 - AUG 26, 07 PALAIS DE TOKYO / PRESS KIT / LA MARQUE NOIRE / LA MARQUE NOIRE / STEVEN PARRINO RETROSPECTIVE, PROSPECTIVE Steven Parrino is considered by many as a model of After FIVE BILLION YEARS and π, the two previous a radical and uncompromising artistic activity, one exhibition programs at the Palais de Tokyo that that disregards the notion of categories and also tested the elasticity and the oscillation of the work places the collaborative process at its core. of art, respectively, LA MARQUE NOIRE considers its resilience. For this program, the Palais de Tokyo Steven Parrino made the apparently inconceivable devotes the entirety of its exhibition spaces to junction between Pop culture and Greenbergian Steven Parrino, who died in a motorcycle accident in modernism. He brought together the aesthetics of January 2005. Conceived as a triptych, the program Hell’s Angels and Minimal Art. Dreaming of creating not only brings together a selection of works by a new Cabaret Voltaire in New York’s No Wave of Parrino, but also presents a collection of works by the 1980s, he conceived of exhibitions where his artists from whom he drew inspiration as well as black monochromes would remain at the mercy of pieces by artists he exhibited, supported, and with the reckless geniuses of noise music, who could whom he collaborated. In this way, LA MARQUE walk all over them. Parrino was the Dr Frankenstein NOIRE covers a field ranging from Minimalism to of painting. A witness to the death of painting, he tattoo art, by way of experimental cinema, cartoons, unremittingly brought it back to life by replacing industrial design, No Wave and punk. -

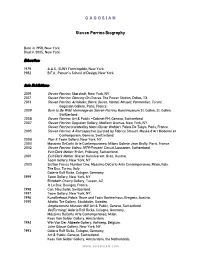

Steven Parrino Biography

G A G O S I A N Steven Parrino Biography Born in 1958, New York. Died in 2005, New York. Education: 1979 A.A.S., SUNY Farmingdale, New York. 1982 B.F.A., Parson’s School of Design, New York. Solo Exhibitions: 2019 Steven Parrino. Skarstedt, New York, NY. 2017 Steven Parrino: Dancing On Graves. The Power Station, Dallas, TX. 2013 Steven Parrino: Armleder, Barré, Buren, Hantaï, Mosset, Parmentier, Toroni. Gagosian Gallery, Paris, France. 2009 Born to Be Wild: Hommage an Steven Parrino, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. 2008 Steven Parrino. Art & Public –Cabinet PH, Geneva, Switzerland. 2007 Steven Parrino. Gagosian Gallery, Madison Avenue, New York, NY. Steven Parrino (curated by Marc-Olivier Wahler). Palais De Tokyo, Paris, France. 2005 Steven Parrino: A Retrospective (curated by Fabrice Stroun). Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland. 2004 Plan 9. Team Gallery, New York, NY. 2003 Massimo DeCarlo Arte Contemporanea, Milano Galerie Jean Brolly, Paris, France. 2002 Steven Parrino Videos 1979-Present. Circuit, Lausanne, Switzerland. Exit/Dark Matter. FriArt, Fribourg, Switzerland. 2001 Exit/Dark Matter. Grazer Kunstverein, Graz, Austria. Team Gallery, New York, NY. 2000 Sicilian Fresco Number One, Massimo DeCarlo Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy. The Box, Torino, Italy. Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne, Germany. 1999 Team Gallery, New York, NY. Elizabeth Cherry Gallery, Tucson, AZ. It. Le Box, Bourges, France. 1998 Can. Neuchatel, Switzerland. 1997 Team Gallery, New York, NY. 1996 Kunstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis Gartnerhaus, Bregenz, Austria. 1995 Misfits. Tre Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden. Amphetamine Monster Mill. Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. De(Forming). Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne, Germany. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Peter Halley Born in 1953, New York, USA Lives and Works in New York

Peter Halley Born in 1953, New York, USA Lives and works in New York Education BA - Yale University MFA - University of New Orleans, 1978 Teaching Columbia University, UCLA School of Visual Arts, SVA 2002-2011 Director of Graduate Studies in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale University School of Art Awards 2001 Frank Jewett Mather Award, College Art Association in the U.S. Solo Exhibitions 2019 Qube, Split, Croatia (collaborative installation with Lauren Clay, catalogue) Heterotopia I, Magazzini del Sale, with Flash Art Magazine and the Accademia di Venezia (installation) Still, Peter Halley and Ugo Rondinone, Stuart Shave/Modern Art Biel train station, Biel, Switzerland (installation) Galerie Forsblom, Stockholm 2018 Peter Halley: Unseen Paintings: 1997-2002, from the Collection of Gian Enzo Sperone, Sperone Westwater, New York New York, New York, The Lever House Art Collection, New York (installation) Peter Halley: New Paintings, Maruani Mercier, Brussels AU-DESSOUS / AU DESSUS, Galerie Xippas, Paris (installation) Peter Halley. Patterns and Figures, Gouaches 1977/78, Galerie Thomas Modern, Munich 2017 Greene Naftali Gallery, New York Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow Boats Crosses Trees Figures Gouaches 1977-78, Karma, New York (catalogue) Peter Halley Paintings from the 1980s, Stuart Shave Modern Art, London (catalogue) 2016 Peter Halley: New Paintings—Associations, Proximities, Conversions, Grids, curated by Richard Milazzo, Galleria Mazzoli, Modena, Italy (catalogue) Peter Halley & Tracy Thomason, Teen Party, Brooklyn, NY Saw: -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Bortolami Gallery

BORTOLAMI Jutta Koether (b. 1958 in Cologne, Germany) Lives and works in New York, New York and Berlin, Germany Solo Exhibitions 2018 Tour De Madame, Museum Brandhorst, Munich, Germany (forthcoming, May) Serralves Foundation, Porto, Portugal (forthcoming) Bortolami, New York, NY (forthcoming) 2017 Jutta Koether/Philadelphia, Bortolami, Philadelphia, PA Serinettes. Ladies Pleasures Varying, Campoli Presti, Paris, France 2016 Best of Studios, Campoli Presi, London, England Zodiac Nudes, Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin, Germany 2015 Fortune, Bortolami, New York, NY 2014 A Moveable Feast – Part XV, Campoli Presti, Paris, France 10th Annual Shanghai Biennial, Shanghai, China Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, Germany Champrovement, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, NY 2013 Etablissement d'en face, Brussels, Belgium Two person show with Gerard Byrne, Praxes Center for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany The Double Session, Campoli Preston, London, United Kingdom Seasons and Sacraments, Arnolfini, Bristol, United Kingdom Seasons and Sacraments, Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, United Kingdom 2012 The Fifth Season, Bortolami, New York, NY 2011 Mad Garland, Campoli Presti, Paris, France The Thirst, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden Berliner Schlüssel, Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin, Germany 2009 Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands Lux Interior, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, NY Sovereign Women in Painting, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA 2008 New Yorker Fenster, Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne, Germany No.5, Kunsthall -

Download Artist's CV

MARUANI MERCIER PETER HALLEY Born in 1953, he lives and works in New York City. Education 1978 BA from Yale University 1980 MFA from the University of New Orleans One Person Exhibitions and Collaborative Exhibitions 2021 Three Paintings, Almine Rech Gallery, Shanghai New Paintings, Galleria Massimo Minini, Brescia, Italy 2020 Peter Halley: New Works, MARUANI MERCIER, Knokke, Belgium Peter Halley: Networks, James Barron Art, Kent, CT Peter Halley: Paintings 2000 – 2018, Galerie Retelet, Monaco Peter Halley / Anselm Reyle, König Galerie and Galerie Thomas, Berlin Peter Halley: New Paintings, Galeria Senda, Barcelona Peter Halley, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen 2019 Heterotopia II, Greene Naftali Gallery, New York Peter Halley: New Paintings, Galerie Thomas Modern, Munich Qube, Split, Croatia (collaborative installation with Lauren Clay, catalogue) Heterotopia I, Magazzini del Sale, with Flash Art Magazine and the Accademia di Venezia (installation) Still, Peter Halley and Ugo Rondinone, Stuart Shave/Modern Art Biel train station, Biel, Switzerland (installation) Galerie Forsblom, Stockholm 2018 Peter Halley: New Paintings, MARUANI MERCIER, Brussels Lever House, New York (installation) Modern I Postmodern: Peter Halley and Robert Mangold, MARUANI MERCIER, Brussels, Belgium AU-DESSOUS / AU DESSUS, Galerie Xippas, Paris (installation) Peter Halley. Patterns and Figures, Gouaches 1977/78, Galerie Thomas Modern, Munich 2017 Greene Naftali Gallery, New York Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow Boats Crosses Trees Figures Gouaches 1977-78, Karma, New York -

Dancing on Graves: Steven Parrino at the Power Station, Dallas, Texas

Terremoto April 15, 2017 GAGOSIAN Dancing on Graves: Steven Parrino at The Power Station, Dallas, Texas Lee Escobedo Exhibition view, Dancing on Graves, Steven Parrino. The Power Station, Dallas, TX. Courtesy of The Power Station. The romance of death is strewn across the Power Station’s floors like poetry. Steven Parrino has finally been given the American survey he deserved, Dancing on Graves at The Power Station in Dallas, Texas. This is the first institutional show for Parrino in the United States, located in an old Dallas Power & Light substation, spanning work made from 1979 to 2004 through painting, works on paper, sculpture, and video. Albeit, the show comes 12 years after he died; riding his own pale horse on New Year’s morning, a motorcycle accident on slippery roads hurdled him towards mortality in 2005 at age 46. If alive today, Parrino would be shocked by none of this new found fame. His work dealt with the comedy of death: his own, his friend’s, of painting. He explored these possibilities by creating large-scale paintings thwarting expectations and academic assumptions on what a painting should look like, be about, and do. Through his work, Parrino was killing his idols, and the canon he was working within, in order for it to evolve further. His work was a dark reflection of minimalism and the monochromatic palette which came before. Parrino’s work treaded theoretically somewhere between Andy Warhol, Yves Klein and the Hells Angels. He attacked flatness with large geometric shaped pieces, like Untitled from 2004, which the Power Station puts on display on the first floor. -

Guide to the Patricia Barnwell Collins Papers MSS.011 Finding Aid Prepared by Molly North and Ryan Evans

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Patricia Barnwell Collins Papers MSS.011 Finding aid prepared by Molly North and Ryan Evans. Collection processed by Molly North; supervised by Ryan Evans. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit October 23, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Guide to the Patricia Barnwell Collins Papers MSS.011 Table of Contents Summary Information..................................................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note.........................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note........................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................ 6 Controlled Access Headings.......................................................................................................................6 -

Pressionism—And Artists Like Pollock, Newman, Still, And, Closer to Home, Stella

P�P�P�P�P�§ P�P�P�P�P�P�§ P�P�P�P�P�P�P� P�P�P�P�P�P�§ P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�§ P�P�P�P�P� P�P�P�§ MAMCO | Musée d’art moderne et contemporain [email protected] T + 41 22 320 61 22 10, rue des Vieux-Grenadiers | CH–1205 Genève www.mamco.ch F + 41 22 781 56 81 P�P�P�P�P�P� P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�P�§ Olivier Mosset (b. 1944) set his sights on a career as an artist after attend- ing an exhibition of works by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg in Bern, in his native Switzerland, in 1962. Early the following year, Mosset headed to Paris to work as an assistant to Jean Tinguely, who introduced him to other members of the Nouveau Réalisme movement—Mosset would later spend brief spells working under Niki de Saint Phalle and Daniel Spoerri—as well as to Otto Hahn, Alain Jouffroy, and other influ- ential critics. Tinguely also arranged for Mosset to meet Andy Warhol in New York. After mixing in these circles, Mosset soon formed his own opin- ions about the artistic debates of the time: wary of lyrical abstraction (the School of Paris), nonplussed by kinetic art, and a keen follower of the emerging Pop art movement. These opinions were reflected in the series of monochrome paintings, each featuring a circle, that he began producing in 1966. And they were views he shared with Daniel Buren, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni. -

Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109

Lorenzo Vitturi, from Money Must Be Made, published by SPBH Editions. See page 125. Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Fall Highlights 110 DESIGNER Photography 112 Martha Ormiston Art 134 IMAGE PRODUCTION Hayden Anderson Architecture 166 COPY WRITING Design 176 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Specialty Books 180 Art 182 FRONT COVER IMAGE Group Exhibitions 196 Fritz Lang, Woman in the Moon (film still), 1929. From The Moon, Photography 200 published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See Page 5. BACK COVER IMAGE From Voyagers, published by The Ice Plant. See page 26. Backlist Highlights 206 Index 215 Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Edited with text by Tracey Bashkoff. Text by Tessel M. Bauduin, Daniel Birnbaum, Briony Fer, Vivien Greene, David Max Horowitz, Andrea Kollnitz, Helen Molesworth, Julia Voss. When Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind more than 1,000 paintings and works on paper that she had kept largely private during her lifetime. Believing the world was not yet ready for her art, she stipulated that it should remain unseen for another 20 years. But only in recent decades has the public had a chance to reckon with af Klint’s radically abstract painting practice—one which predates the work of Vasily Kandinsky and other artists widely considered trailblazers of modernist abstraction. Her boldly colorful works, many of them large-scale, reflect an ambitious, spiritually informed attempt to chart an invisible, totalizing world order through a synthesis of natural and geometric forms, textual elements and esoteric symbolism.