Pressionism—And Artists Like Pollock, Newman, Still, And, Closer to Home, Stella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

The School of Paris Catalogue

THE SCHOOL OF PARIS 12 MARCH - 28 APRIL 2016 Francis Bacon (1909 - 1992) Title: Woodrow Wilson, Paris, 1919, from Triptych (1986-1987) Medium: Original Etching and aquatint in colours, 1986/8, on wove paper, with full margins, signed by the artist in pencil Edition: 38/99 - There were also 15 Hors Commerce copies There were also 15 artists proofs in Roman numerals. Literature: Bruno Sabatier, "Francis Bacon: Oeuvre Graphique-Graphic Work. Catalogue Raisonné", JSC Modern Art Gallery, París 2012 Note: The present work is taken from an old press cutting of Woodrow Wilson in Paris for the Peace Conference of 1919. It was originally part of a triptych of works which included a study for the portraits of John Edwards and a Photograph of Totsky studio in Mexico in 1940. Woodrow Wilson (1856 - 1924) was the 28th President of the United States, elected President in 1912 and again in 1916. Published by: Editions Poligrafa, Barcelona, Spain Size: P. 25½ x 19¼ in (648 x 489 mm.) S. 35¼ x 24½ in. (895 x 622 mm.) George Braque (1882 - 1963) Title: Feuillage en couleurs Foliage in colours Medium: Etching in colours, circa 1956, on BFK Rives watermarked paper, signed by the artist in pencil, with blindstamp "ATELIER CROMMELYNCK PRESSES DUTROU PARIS" Size: Image size: 440 x 380 MMS ; Paper size 500 X 670 mms Edition: XVI/XX Publisher: The Society des Bibliophiles de France, Paris Note: There was also a version of this in Black and White which was possibly a state of our piece (Vallier 106) Reference: Dora Vallier “Braque: The Complete Graphics” Number 105 after George Braque (1882 - 1963) Title: Les Fleurs Violets Bouquet des Fleurs Medium: Etching and Aquatint in colours, circa 1955/60, on Arches watermarked paper, signed by the artist in pencil, with blindstamp "ATELIER CROMMELYNCK PARIS" Size: Image size: 19 in x 11 5/8 in (48.3 cm x 29.5 cm) ; Paper size 26 in x 19 3/4 in (66 cm x 50.2 cm) Edition: 92/200 - There was also an edition of 50 on Japan paper. -

Olivier Mosset Art Basel 2018 Olivier Mosset

Olivier Mosset Art Basel 2018 Olivier Mosset Untitled "Blue / purple / blue", 2 0 0 8 acrylic on canvas 197 1.773 4,5 cm Unlimited, hall 1.1., U48 Olivier Mosset, Untitled (blue / purple / blue), 2008 197 x 1773 x 4.5 cm, acrylic on canvas « Une fourmi de dix-huit mètres […] ça n'existe pas » – Robert Desnos (engl. « An eighteen-metre ant […] doesn't exist ») Olivier Mosset, born in 1944 in Bern, once a member of the famous BMPT group with Daniel Buren, Niele Toroni and Michel Parmentier, who sought to democratize art through radical procedures of deskilling, implying that the art object was more important than its authorship, is nowadays widely recognized for his conducting of research into the future of painting through geometrical abstraction and monochromes. Living between two continents since 1977, Mosset remains one of the few artists in Europe that is involved in the French, Swiss and American artistic and critical contexts. Dating from 2008, the extremely large format acrylic canvas Untitled (blue / purple / blue), measuring 197 x 1773 cm and consisting of a group of three panels, each 2 x 6 meters and covered with blue and purple colour, does not represent a break with his early work, but should be regarded as a re-start, a re-presentation or even a re-production that continues his quest for blurring the margins of art. When we asked Olivier Mosset about the story behind this large format canvas he answered: “There is no story, but it was made and shown in China. Then Mosset reveals: “In fact, the story of China was that I met this gentlemen and they had this gallery that was pretty big and someone said: ‘Olivier, you have done 6 meter high monochromes in blue / yellow and pink / purple, you should do something like that’. -

PETER HALLEY Biografía

BARCELONA GALLERY WEEKEND 2020 galeria SENDA PETER HALLEY Biografía Peter Halley (Nueva York, 1953) se dio a conocer a mediados de los años ochenta en Nueva York como impulsor del Neo-conceptualismo, corriente que aparece como reacción al neoim- presionismo y que supone un resurgimiento de la abstracción geométrica. Su estilo refleja la idea del lenguaje como sistema estable y autorreferencial, y critica las reivindicaciones tras- cendentales del minimalismo. Además, su obra presenta una influencia por la teoría social del Estructuralismo, la cual plantea el análisis de los sistemas socioculturales y de los lenguajes, a partir de configuraciones y estructuras simbólicas profundas, que condicionan y determinan todo lo que ocurre en la actividad humana. Así pues, las celdas y los conductos que Peter Ha- lley articula y combina en sus lienzos, no son una simple composición geométrica abstracta, sino más bien una imagen simbólica de los esquemas sociales que nos rodean. “En nuestra cultura, la geometría se suele considerar un signo de lo racional. Yo, por algún motivo, considero que es al revés, que la geometría posee una significación primaria, más psi- cológica que intelectual”, afirma en su ensayo “La Geometría y lo Social” de 1991. Peter Halley ha sido director de estudios de pintura de la Universidad de Yale y ha impartido clases en la Universidad de Columbia, en UCLA y en la Escuela de Artes Visuales de Nueva York. De 1996 a 2005 fue editor de la revista cultural Index Magazine. Ha realizado exposicio- nes individuales en la Academia de Arte de la Bienal de Venecia, en el contexto de la Bienal de Venecia de 2019, el MoMA de Nueva York en 1997 y el Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía de Madrid en 1992. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Julia Wachtel

NO. 5 ˚2 Julia Wachtel BERGEN KUNSTHALL BERGEN KUNSTHALL Julia Wachtel Animating the Painted Stage Bob Nickas The audience has seen it all before: pop, minimal, mini-mall, Rod Stewart side-by-side, a beaming John Travolta and a expressionism, neo-ex, neo-this-n-that, pantomime, pictures sullen, androgynous supermodel, Mussolini appearing to of pictures. The ventriloquist whose lips won’t stop moving, salute a near-naked woman. This latter work’s title, Relations the guy in the fright-wigs, the blunder and bluster of plates in Of Absence (1981) is particularly revealing. As Wachtel pairs mid-air—crashing down, as if on cue, shattered crockery on otherwise unrelated, unknown and unknowable figures, she the canvas floor. The snake charmer, the shiny rabbit pulled registers an emotional void that defines our ‘connectivity’ from the same old hat, the comedian who rarely manages a to them, calling attention to a space which is physically but laugh. Listen to the sound of that sad low groan. And then, not psychically seamless. And then we notice that life-size as the lights dim, a wheezing bum note trumpets the chatter silhouettes have been overlaid with black marker, and the in the room, the horn player on his last desultory breath. The effect suggests that members of a movie audience on their crowd quiets and the emcee appears, a goofball bounced way to or from their seats have blocked the light between the from a box of lucky charms, one big tooth in the gaping projector and the screen.1 Viewed in this way, the sequence hole of a silly grin, a stark contrast to the red velvet curtains of images takes on the appearance of an illuminated stage, as behind. -

LA Marque Noire

PALAIS DE TOKYO / PRESS KIT / LA MARQUE NOIRE / LA MARQUE NOIRE / STEVEN PARRINO RETROSPECTIVE, PROSPECTIVE MAY 24 - AUG 26, 07 PALAIS DE TOKYO / PRESS KIT / LA MARQUE NOIRE / LA MARQUE NOIRE / STEVEN PARRINO RETROSPECTIVE, PROSPECTIVE Steven Parrino is considered by many as a model of After FIVE BILLION YEARS and π, the two previous a radical and uncompromising artistic activity, one exhibition programs at the Palais de Tokyo that that disregards the notion of categories and also tested the elasticity and the oscillation of the work places the collaborative process at its core. of art, respectively, LA MARQUE NOIRE considers its resilience. For this program, the Palais de Tokyo Steven Parrino made the apparently inconceivable devotes the entirety of its exhibition spaces to junction between Pop culture and Greenbergian Steven Parrino, who died in a motorcycle accident in modernism. He brought together the aesthetics of January 2005. Conceived as a triptych, the program Hell’s Angels and Minimal Art. Dreaming of creating not only brings together a selection of works by a new Cabaret Voltaire in New York’s No Wave of Parrino, but also presents a collection of works by the 1980s, he conceived of exhibitions where his artists from whom he drew inspiration as well as black monochromes would remain at the mercy of pieces by artists he exhibited, supported, and with the reckless geniuses of noise music, who could whom he collaborated. In this way, LA MARQUE walk all over them. Parrino was the Dr Frankenstein NOIRE covers a field ranging from Minimalism to of painting. A witness to the death of painting, he tattoo art, by way of experimental cinema, cartoons, unremittingly brought it back to life by replacing industrial design, No Wave and punk. -

Abstraction Joan Miró

visions of Abstraction Joan Miró Alexander Calder Jean Dubuffet Antoni Tàpies Yayoi Kusama Opera Gallery Dubai is proud to bring to you artworks by some of the greatest artists who have made history in the 19th Century and by the inheritors of the breakthrough movement they initiated, including Joan Miró, Jean Dubuffet, Hans Hartung Victor Vasarely Sam Francis, Hans Hartung, Yayoi Kusama, André Lanskoy, Georges Mathieu, Victor Vasarely, Damien Hirst and Marcello Lo Giudice. André Lanskoy Damien Hirst The abstract art movement has used a visual language of forms, colours and lines to create compositions indepen- Georges Mathieu Ron Agam dently from the world’s visual references. In doing so, the abstract artists have chosen to interpret a subject without providing their viewer with a known or recognisable reference to explain it; therefore contrasting dramatically with Pierre Soulages Umberto Ciceri the more traditional forms of art that, until then, had tried to achieve a rather literal interpretation of the world and communicate a sense of reality to the viewer. Freeing themselves from the obligation to depict the subject as it appears, Sam Francis Nasrollah Afjei the abstract artists take us into a new artistic territory and they make possible the representation of intangible emotions, such as beliefs, fears or passions. ‘Visions of Abstraction’ will unveil a carefully curated collection of some of the major artists that have redefined abstract art as well as illustrate the different styles of abstraction that coexist in today’s global art world. Among others that we invite you to discover, we are proud to feature Joan Miró - whose revolutionary art ranges from automatic drawing and surrealism, to expressionism, lyrical abstraction, and colour field painting; David Mach and p r e f a c e his contemporary homage to Jackson Pollock’s 1960s’ abstract expressionism; Katrin Fridriks' conceptual abstract painting; and Yayoi Kusama’s repetitive pop art. -

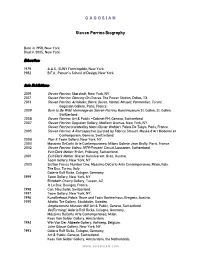

Steven Parrino Biography

G A G O S I A N Steven Parrino Biography Born in 1958, New York. Died in 2005, New York. Education: 1979 A.A.S., SUNY Farmingdale, New York. 1982 B.F.A., Parson’s School of Design, New York. Solo Exhibitions: 2019 Steven Parrino. Skarstedt, New York, NY. 2017 Steven Parrino: Dancing On Graves. The Power Station, Dallas, TX. 2013 Steven Parrino: Armleder, Barré, Buren, Hantaï, Mosset, Parmentier, Toroni. Gagosian Gallery, Paris, France. 2009 Born to Be Wild: Hommage an Steven Parrino, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. 2008 Steven Parrino. Art & Public –Cabinet PH, Geneva, Switzerland. 2007 Steven Parrino. Gagosian Gallery, Madison Avenue, New York, NY. Steven Parrino (curated by Marc-Olivier Wahler). Palais De Tokyo, Paris, France. 2005 Steven Parrino: A Retrospective (curated by Fabrice Stroun). Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland. 2004 Plan 9. Team Gallery, New York, NY. 2003 Massimo DeCarlo Arte Contemporanea, Milano Galerie Jean Brolly, Paris, France. 2002 Steven Parrino Videos 1979-Present. Circuit, Lausanne, Switzerland. Exit/Dark Matter. FriArt, Fribourg, Switzerland. 2001 Exit/Dark Matter. Grazer Kunstverein, Graz, Austria. Team Gallery, New York, NY. 2000 Sicilian Fresco Number One, Massimo DeCarlo Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy. The Box, Torino, Italy. Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne, Germany. 1999 Team Gallery, New York, NY. Elizabeth Cherry Gallery, Tucson, AZ. It. Le Box, Bourges, France. 1998 Can. Neuchatel, Switzerland. 1997 Team Gallery, New York, NY. 1996 Kunstlerhaus Palais Thurn und Taxis Gartnerhaus, Bregenz, Austria. 1995 Misfits. Tre Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden. Amphetamine Monster Mill. Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. De(Forming). Galerie Rolf Ricke, Cologne, Germany. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

The School of Paris” and “The Making of the Modern”

INTRO INTO “THE SCHOOL OF PARIS” AND “THE MAKING OF THE MODERN” Shemer Art Center March 19, 2015 5005 E Camelback Rd 6pm Phoenix, AZ 85018 $5 donation Presentation by Jeralynn Benoit Several years ago, PBS presented, Paris, The Luminous Years which explored the unique moment in Paris from 1905 to 1929 in the world of art. The city of Paris was a major catalyst for artists in nearly every artistic discipline. These were pivotal years for our contemporary culture, when an international group including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Igor Stravinsky, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Vaslav Nijinsky and Aaron Copland, among numerous others, revolutionized the direction of the modern arts. In the early decades of the twentieth century, a storm of modernism swept through the art worlds of the West, displacing centuries of tradition in the visual arts, music, literature, dance, theater and beyond. The epicenter of this storm was Paris, France. My digital presentation is my version of the story. The importance of a particular place in artistic creation is fascinating. At this time period, Paris was the magnet; the impetus and the transforming force that attracted the finest talents of the era, molding the lives and work of two remarkable generations. Why Paris? For avant-garde painters and sculptors, Paris provided crucial access to daring art dealers who were ready to show, buy and sell their work. For young American authors and poets, their radically innovative literature ̶ often rejected by major American publishers ̶ was embraced and published in Paris by equally young, American publishers with small, independent presses. -

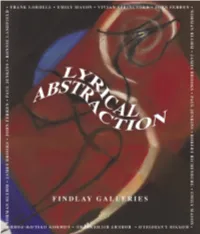

Lyrical Abstraction

Lyrical Abstraction Findlay Galleries presents the group exhibition, Lyrical Abstraction, showcasing works by Mary Abbott, Norman Bluhm, James Brooks, John Ferren, Gordon Onslow Ford, Paul Jenkins, Ronnie Landfield, Frank Lobdell, Emily Mason, Irene Rice Pereira, Robert Richenburg, and Vivian Springford. The Lyrical Abstraction movement emerged in America during the 1960s and 1970s in response to the growth of Minimalism and Conceptual art. Larry Aldrich, founder of the Aldrich Museum, first coined the term Lyrical Abstraction and staged its first exhibition in 1971 at The Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition featured works by artists such as Dan Christensen, Ronnie Landfield, and William Pettet. David Shirey, a New York Times critic who reviewed the exhibition, said, “[Lyrical Abstraction] is not interested in fundamentals and forces. It takes them as a means to an end. That end is beauty...” Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings and Mark Rothko’s stained color forms provided important precedence for the movement in which artists adopted a more painterly approach with rich colors and fluid composition. Ronnie Landfield, an artist at the forefront of Lyrical Abstraction calls it “a new sensibility,” stating: ...[Lyrical Abstraction] was painterly, additive, combined different styles, was spiritual, and expressed deep human values. Artists in their studios knew that reduction was no longer necessary for advanced art and that style did not necessarily determine quality or meaning. Lyrical Abstraction was painterly, loose, expressive, ambiguous, landscape-oriented, and generally everything that Minimal Art and Greenbergian Formalism of the mid-sixties were not. Building on Aldrich’s concept of Lyrical Abstractions, Findlay Galleries’ exhibition expands the definition to include artists such as John Ferren, Robert Richenburg and Frank Lobdell.