Jazz Solo Transcriptions As Technical and Pedagogical Solutions for Undergraduate Jazz Saxophonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Juilliard Jazz Ensembles

The Juilliard School Presents Juilliard Jazz Ensembles Monday, January 29, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall The Music of Miles Davis Wynton Marsalis, Guest Coach Dizzy Gillespie Ensemble Swing Spring (Miles Davis, arr. Joel Wenhardt) Flamenco Sketches (Miles Davis and Bill Evans, arr.Andrea Domenici) Nardis (Miles Davis, arr. Jeffery Miller) Paraphernalia (Wayne Shorter, arr. Adam Olszewski) Half Nelson (Miles Davis, arr. David Milazzo) David Milazzo, Alto Saxophone Anthony Hervey, Trumpet Jeffery Miller, Trombone Andrea Domenici, Piano Joel Wenhardt, Piano Adam Olszewski, Bass Cameron MacIntosh, Drums Elio Villafranca, Resident Coach Intermission (Program continues) Juilliard gratefully acknowledges the Talented Students in the Arts Initiative, a collaboration for the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Surdna Foundation, for their generous support of Juilliard Jazz. Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation in memory of Josephine Bay Paul. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. 1 The Dave Brubeck Ensemble Dig (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Fall (Wayne Shorter, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Milestones (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Circle (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) So Near, So Far (Tony Crombie and Bennie Green, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Zoe Obadia, Alto Saxophone Noah Halpern, Trumpet Jasim Perales, Trombone Joseph Block, Piano Isaiah Thompson, Piano Adam Olszewski, Bass Francesco Ciniglio, Drums Helen Sung, Resident Coach Program order and selections are subject to change. -

Flute Comp Exam Scoring Rubric

Flute Comp Exam Scoring Rubric Name_____________________________________________________ Date_________________ 1 Unsatisfactory 2 Basic 3 Proficient 4 Distinguished Embouchure Shifts Poor concept of embouchure Basic ability to shift from 2nd Generally good embouchure Consistent skill in executing shifts; difficulty executing octave down to 1st octave flexibility; difficulties isolated embouchure shifts throughout throughout to one or two octaves exercise Embouchure Shifts Poor concept of embouchure Basic ability to shift from 2nd Generally good embouchure Consistent skill in executing shifts; difficulty executing octave up to 3rd octave flexibility; difficulties isolated embouchure shifts throughout throughout to one or two octaves exercise Chromatic Scale Numerous hesitations; lacks Somewhat lacking in fluency Minimal hesitation in Fluid technical performance technical fluency and and precision of technique; technical fluency; good and precision even in the 3rd precision; struggles with difficulty with chromatic knowledge of chromatic octave; secure knowledge of knowledge of chromatic fingerings in 3rd octave fingerings all chromatic fingerings fingerings Arpeggio Difficulty shifting embouchure Basic ability to shift from 1st Generally fluid performance; Fluid performance of shifting from octave to octave; 3rd octave to 2nd octave and play 3rd octave shift slightly from octave to octave; good octave forced & out of tune; in tune; difficulty going into troublesome; fingerings were intonation incorrect 3rd octave fingerings 3rd octave; -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

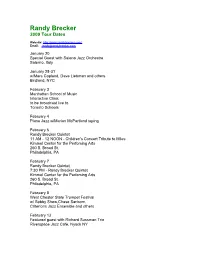

2009 Tour Dates

Randy Brecker 2009 Tour Dates Website: http://www.randybrecker.com/ Email: [email protected] January 20 Special Guest with Saleno Jazz Orchestra Salerno, Italy January 28-31 w/Marc Copland, Dave Liebman and others Birdland, NYC February 3 Manhattan School of Music Interactive Clinic to be broadcast live to Toronto Schools February 4 Piano Jazz w/Marian McPartland taping February 6 Randy Brecker Quintet 11 AM - 12 NOON - Children's Concert Tribute to Miles Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 7 Randy Brecker Quintet 7:30 PM - Randy Brecker Quintet Kimmel Center for the Perfoming Arts 260 S. Broad St. Philadelphia, PA February 8 West Chester State Trumpet Festival w/ Bobby Shew,Chase Sanborn, Criterions Jazz Ensemble and others February 13 Featured guest with Richard Sussman Trio Riverspace Jazz Cafe, Nyack NY February 15 Special guest w/Dave Liebman Group Baltimore, Maryland February 20 - 21 Special guest w/James Moody Quartet Burmuda Jazz Festival March 1-2 Northeastern State Universitry Concert/Clinic Tahlequah, Oklahoma March 6-7 Concert/Clinic for Frank Foster and Break the Glass Foundation Sandler Perf. Arts Center Virginia Beach, VA March 17-25 Dates TBA European Tour w/Lynne Arriale quartet feat: Randy Brecker, Geo. Mraz A. Pinciotti March 27-28 Temple University Concert/Clinic Temple,Texas March 30 Scholarship Concert with James Moody BB King's NYC, NY April 1-2 SUNY Purchase Concert/Clinic with Jazz Ensemble directed by Todd Coolman April 4 Berks Jazz Festival w/Metro Special Edition: Chuck Loeb, Dave Weckl, Mitch Forman and others April 11 w/ Lynne Arriale Jazz Quartet Ft. -

Wind Orchestra

caltech-occidental wind orchestra The Caltech - Occidental Wind Orchestra is comprised of select performers of wind and percussion instruments drawn from the undergraduate and graduate student population at Caltech and Occidental College, plus faculty, alumni, staff and community members from Caltech, and the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratories (JPL). Currently numbering at approximately 80 musicians, this group rehearses once per week and performs three programs of repertoire per academic year. The repertoire is selected from the finest traditional and contemporary music from around the world. The ensemble (formerly known as the Concert Band) earned great acclaim under the leadership of William Bing, who directed the group for over 40 years. Drawing upon the tremendous talent base of Los Angeles, the group has featured such guest artists as Allen Vizzuti, David Shifrin, Eddie Daniels, Jim Self, Wayne Bergeron and Frank Ticheli. The group has taken on notable recording projects, and tours to such locations as Carnegie Hall and China. Appointed in 2016 as conductor of the ensemble and Director of Performing and Visual Arts, Glenn Price is building on the heritage, tradition and high standards established by Bill Bing. DR. GLENN D. PRICE, CONDUCTOR CALTECH-OCCIDENTAL Dr. Glenn D. Price has earned an international reputation as a leading conductor and educator through his experience conducting student, community and professional symphony orchestras wind orchestra and wind ensembles in over 30 countries. He has conducted many renowned soloists, including Evelyn Glennie, Christian Lindberg, Ney Rosauro, Jens Lindemann, Alain Trudel, Roger Webster, Kenneth Tse, Adam Frey, Simone Rebello, David Campbell, John Marcellus and Michael Burritt. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Trent 91; First Steps Towards a Stylistic Classification (Revised 2019 Version of My 2003 Paper, Originally Circulated to Just a Dozen Specialists)

Trent 91; first steps towards a stylistic classification (revised 2019 version of my 2003 paper, originally circulated to just a dozen specialists). Probably unreadable in a single sitting but useful as a reference guide, the original has been modified in some wording, by mention of three new-ish concordances and by correction of quite a few errors. There is also now a Trent 91 edition index on pp. 69-72. [Type the company name] Musical examples have been imported from the older version. These have been left as they are apart from the Appendix I and II examples, which have been corrected. [Type the document Additional information (and also errata) found since publication date: 1. The Pange lingua setting no. 1330 (cited on p. 29) has a concordance in Wr2016 f. 108r, whereti it is tle]textless. (This manuscript is sometimes referred to by its new shelf number Warsaw 5892). The concordance - I believe – was first noted by Tom Ward (see The Polyphonic Office Hymn[T 1y4p0e0 t-h15e2 d0o, cpu. m21e6n,t se suttbtinigt lneo] . 466). 2. Page 43 footnote 77: the fragmentary concordance for the Urbs beata setting no. 1343 in the Weitra fragment has now been described and illustrated fully in Zapke, S. & Wright, P. ‘The Weitra Fragment: A Central Source of Late Medieval Polyphony’ in Music & Letters 96 no. 3 (2015), pp. 232-343. 3. The Introit group subgroup ‘I’ discussed on p. 34 and the Sequences discussed on pp. 7-12 were originally published in the Ex Codicis pilot booklet of 2003, and this has now been replaced with nos 148-159 of the Trent 91 edition. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.