9781925021493.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8. Aboriginal Water Values and Uses

Chapter 8. Aboriginal water values and uses Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 8. Aboriginal water values and uses The Murray-Darling Basin Plan requires Basin states to identify objectives and outcomes of water, based on Aboriginal values and uses of water, and have regard to the views of Traditional Owners on matters identified by the Basin Plan. Victoria engaged with Traditional Owner groups in the Water Resource Plan for the northern Victoria area to: • outline the purpose, scope and opportunity for providing water to meet Traditional Owner water objectives and outcomes through the Murray-Darling Basin Plan • define the role of the water resource plans in the Basin, including but not limited to the requirements of the Basin Plan (Chapter 10, Part 14) • provide the timeline for the development and accreditation of the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan • determine each Traditional Owner group’s preferred means of engagement and involvement in the development of the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan • continue to liaise and collaborate with Traditional Owner groups to integrate specific concerns and opportunities regarding the water planning and management framework. • identify Aboriginal water objectives for each Traditional Owner group, and desired outcomes The Water Resource Plan for the Northern Victoria water resource plan area, the Victorian Murray water resource plan area and the Goulburn-Murray water resource plan area is formally titled Victoria’s North and Murray Water Resource Plan for the purposes of accreditation. When engaging with Traditional Owners this plan has been referred to as the Northern Victoria Water Resource Plan and is so called in Chapter 8 of the Comprehensive Report. -

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

AFL Coaching Newsletter - April 2009

AFL Coaching Newsletter - April 2009 THE NEW SEASON Most community football leagues around Australia kick off this weekend or immediately after Easter and NAB AFL Auskick Centres commence their programs in the next month. This newsletter focuses on a range of topics which are relevant to the commencement of the 2009 Australian Football season. PLAYING AND TRAINING IN HOT CONDITIONS The new season generally starts in warm to hot conditions and there is always a lift in intensity once the premiership season proper starts. Regardless of the quality of pre-season training programs, early games are usually more stressful and players and coaches should keep safety factors associated with high intensity exercise in warm conditions in mind – these include individual player workloads (use of the bench), hydration and sun sense. The following article by AIS/AFL Academy dietitian Michelle Cort provides good advice regarding player hydration. Toughen Up - Have a Drink! Why are so many trainers necessary on a senior AFL field and why they are constantly approaching players for a drink during a game? Obviously the outcome of not drinking enough fluid is dehydration. The notion of avoiding fluid during sport to ‘train’, ‘toughen’ or ‘adjust’ an athlete’s body to handle dehydration is extremely outdated & scientifically incorrect. Even very small amounts of dehydration will reduce an AFL player’s performance. Most senior AFL conditioning, nutrition and medical staff invest considerable time into ensuring the players are doing everything possible to prevent significant dehydration from occurring in training and games. The effects on performance are not limited to elite athletes. -

Southern Azeris Seething

NOT FOR PUBLICAT'i'ON WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS tcg-22 May .--, 1992 Dear Peter, It has been pretty hectic around here, and so rather than dely my nxt pitl to you ny longer I tho,,qht_ I wn,Id pnd this out-of-sync, stop-gap offering lest you start thinking I have fallen asleep. I have not. I have been in high-speed over-drive on an un-tracked roller coaster course for the past month. You will hear all about it once I have time to breath. But j,, to give you a sense of what has been going on since our last communication I will provide the following summary. My last letter to you was an offering with the title: Everything You Never Wanted To Know About Azerbaijan= Typically for a Goltz ICWA epistle, it started as an eight page idea and grew into a monster manuscript. And it wasn't even finished. I had planned on sendinq two more instal I ments But in the midst- of the editing o Part Two I received a freak v t,3 I ran, and had to drop everything to get there before the visa limitations closed: I was, in effect, the first American tourist to the Islamic Republic in a decade. I had a wonderful time and kept a daily nohnnk that I plan to turn into another monster manuscript. The report that follows, cast as an article, is but a fraction of the IC".AA letter I was working on, but It will give a #te what is to come Anyway, I was editing the manuscript on the hoof and had just left _rran to do a loop around Mount Ararat in eastern Turkey to return to Baku via Nakhichivan when the poop hit the fan: The Armenians were attacking the obscure Azeri enclave, and once more Your6Truly was in a hot-spot by accident. -

The History of Cultural Production in the United States Tracks the Racial Divide That Inaugurated the Founding of the Republic

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AT THE INTERSECTION OF RACE AND GENDER: OR LADY 1 SINGS THE BLUES BY K.J. GREENE The history of cultural production in the United States tracks the racial divide that inaugurated the founding of the Republic. The original U.S. Constitution excluded both black women and men from the blessings of liberty. Congress enacted formal laws mandating racial equality only scant decades ago, although it may seem long ago to today’s generation. Interestingly, the same Constitution that validated slavery and excluded women from voting also granted rights to authors and inventors in what is known as the Patent/Copyright clause of Article I, section 8. Those rights have become the cornerstone of economic value not only in the U.S but globally, and are inextricably tied to cultural production that influences all aspects of society. My scholarship seeks to show how both the structure of copyright law, and the phenomena of racial segregation and discrimination impacted the cultural production of African-Americans and how the racially neutral construct of IP has in fact historically adversely impacted African- American artists.2 It is only in recent years that scholarship exploring intellectual property has examined IP in the context of social and historical inequality. This piece will explore briefly how women artists and particularly black women have been impacted in the IP system, and to compare how both blacks and women have shared commonality of treatment with indigenous peoples and their creative works. The treatment of blacks, women and indigenous peoples in the IP system reflects an unfortunate narrative of exploitation, devaluation and the promotion of derogatory stereotypes that helped fuel oppression in the United States and in the case of indigenous peoples, aboard. -

Calendar of Observances 2021

Calendar of Observances 2021 The increasingly pluralistic population of the United States is made up of many different ethnic, cultural, faith and religious communities. To enhance mutual understanding among groups and promote inclusive communities, the ADL offers this resource as a tool to increase awareness of and respect for religious obligations and ethnic and cultural festivities that may affect students, colleagues and neighbors in your community. Religious Observations The calendar includes significant religious observances of the major faiths represented in the United States. It can be used when planning school exam schedules and activities, workplace festivities and community events. Note that Bahá’í, Jewish and Islamic holidays begin at sundown the previous day and end at sundown on the date listed. National and International Holidays The calendar notes U.S. holidays that are either legal holidays or observed in various states and communities throughout the country. Important national and international observances that may be commemorated in the U.S. are also included. Calendar System The dates of secular holidays are based on the Gregorian calendar, which is commonly used for civil dating purposes. Many religions and cultures follow various traditional calendar systems that are often based on the phases of the moon with occasional adjustments for the solar cycle. Therefore, specific Gregorian calendar dates for these observances will differ from year to year. In addition, calculation of specific dates may vary by geographical location and according to different sects within a religion. [NOTE: Observances highlighted in yellow indicate that the dates are tentative or not yet set by the organizations who coordinate them.] © 2020 Anti-Defamation League Page 1 https://www.adl.org/education/resources/tools-and-strategies/calendar-of-observances January 2021 January 1 NEW YEAR’S DAY The first day of the year in the Gregorian calendar, commonly used for civil dating purposes. -

Download Sponsorship Packages

Sponsorship Opportunity We believe all kids deserve a fair go. Our mission is to empower children who are facing challenges with sickness, disadvantage or through living with disability to reach their full potential and their dreams. We strive to support all children to attain their full potential, regardless of ability or background. Last year alone we provided $1,666,468 in grants in Victoria impacting 12,290 Victorian children. Variety along with Jason Dunstall and Danny Frawley want YOU at this Year’s Footy Lunch with Heart! Officially endorsed by the AFL, the Variety Toyota AFL Grand Final Lunch has been kicking goals for disadvantaged children for over 30 years. Through the support of the football community, this Melbourne institution has changed the lives of thousands of Aussie children and their families. On the Wednesday before Grand Final, the Palladium at Crown is transformed by football mania as media, celebrities, the football fraternity and eager lunch-goers all converge to make this the football lunch of the year. Event capacity is 1300, individual ticket is $195pp, Table of 10 $1950, includes: A three-course lunch and premium drinks package Live entertainment FUNraising – raffles, prizes, live and silent auction + loads more AFL/AFLW stars, AFL legends, AFL coaches, AFL Premiership Cup Ambassador on stage Presentation of the Tom Hafey Heart of Football and Young Sports Achiever Awards The event is hosted by the voice of football Craig Willis and co-host Sharni Layton! In 2018, 1212 people attended the Variety Toyota AFL Grand Final Lunch. The demographic of people that attend the event are 70% males (aged 20 – 50+) and 30% females (aged 30 -50), target audience includes trades 50%, corporates 40%, other 10%. -

Fishing on Information Further For

• www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/recreational at online View any time. any of fish that a person is allowed to have in their possession at at possession their in have to allowed is person a that fish of waters: NSW for rules fishing on information further For • Possession limits: Possession type particular a of number maximum The phones. smart and waters; identified the in taken • for app Guide Fishing Recreational Victorian the Download • Closed seasons: Closed be cannot species fish certain which in period the • or ; www.vic.gov.au/fisheries at online View • Bag limits: Bag day; one in take to permitted are you fish of number • ; 186 136 on Centre Service Customer Call it; keep to allowed be to you for and practices: and • Size limits: Size minimum or maximum size a fish must be in order order in be must fish a size maximum or minimum Recreational Fishing Guide for further information on fishing rules rules fishing on information further for Guide Fishing Recreational recreational fishing. Rules and regulations include: regulations and Rules fishing. recreational Obtain a free copy of the Inland Angling Guide and the Victorian Victorian the and Guide Angling Inland the of copy free a Obtain It is important to be aware of the rules and regulations applying to to applying regulations and rules the of aware be to important is It From most Kmart stores in NSW. in stores Kmart most From • Lake Mulwala Angling Club Angling Mulwala Lake • Fish By the Rules the By Fish agents, and agents, Nathalia Angling Club Angling Nathalia • From hundreds of standard and gold fishing fee fee fishing gold and standard of hundreds From • Numurkah Fishing Club Fishing Numurkah • By calling 1300 369 365 (Visa and Mastercard only), only), Mastercard and (Visa 365 369 1300 calling By • used to catch Spiny Freshwater Crayfish. -

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture

The History of NAIDOC Celebrating Indigenous Culture latrobe.edu.au CRICOS Provider 00115M Wominjeka Welcome La Trobe University 22 Acknowledgement La Trobe University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Bundoora campus is located. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 33 Acknowledgement We recognise their ongoing connection to the land and value the unique contribution the Wurundjeri people and all Indigenous Australians make to the University and the wider Australian society. LaLa Trobe Trobe University University 44 What is NAIDOC? NAIDOC stands for the ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’. This committee was responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week and its acronym has since become the name of the week itself. La Trobe University 55 History of NAIDOC NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in Indigenous communities, but by Australians from all walks of life. La Trobe University 66 History of NAIDOC 1920-1930 Before the 1920s, Aboriginal rights groups boycotted Australia Day (26 January) in protest against the status and treatment of Indigenous Australians. Several organisations emerged to fill this role, particularly the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. La Trobe University 77 History of NAIDOC 1930’s In 1935, William Cooper, founder of the AAL, drafted a petition to send to King George V, asking for special Aboriginal electorates in Federal Parliament. The Australian Government believed that the petition fell outside its constitutional Responsibilities William Cooper (c. -

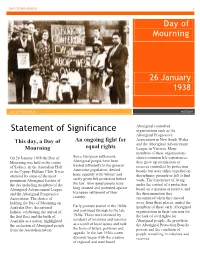

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Click Here to View Asset

Published by Arts Victoria. The views expressed in this publication are based on information provided by third party authors. Arts Victoria does not necessarily endorse the views of a particular author. All information contained in this publication is considered correct at the time of printing. Arts Victoria VIAA PRE -SELECTION PANEL EXHIBITION CURATORS , Private Bag No. 1 Maree Clarke, Curatorial Manager, DESIGN AND HANGING South Melbourne 3205 Koorie Heritage Trust; Stephen Boscia Galleries Victoria Australia Gilchrist, Curator – Indigenous Art, PHOTOGRAPHY TELEPHONE 03 9954 5000 National Gallery of Victoria; Jirra Harvey, Freelance Curator. Ponch Hawkes FACSIMILE 03 9686 6186 CATALOGUE DESIGN TTY 03 9682 4864 VIAA FINAL JUDGING PANEL AND SPONSORS Actual Size TOLL FREE 1800 134 894 Lorraine Coutts, Indigenous Curator; (Regional Victoria only) Kevin Williams, Indigenous artist; PRINTED BY [email protected] Zara Stanhope, freelance Curator; Gunn and Taylor Printers www.arts.vic.gov.au Stephen Gilchrist, Curator – Indigenous Art, National Gallery The VIAA exhibition runs from of Victoria; Judith Ryan, Senior 29 November to 20 December Curator – Indigenous Art, National 2008, Boscia Galleries, Melbourne Gallery of Victoria; Jason Eades, Victoria, 3000. CEO – Koorie Heritage Trust; Nerissa The exhibition is free and open to Broben, Curatorial Manager – Koorie the public. Heritage Trust; Chris Keeler, Curatorial Assistant – Koorie Artworks featured in the VIAA Heritage Trust. exhibition are available for purchase. This publication is copyright. No part SPONSORS ’ REPRESENTATIVES Michele and Anthony Boscia, may be reproduced by any process Boscia Galleries. except in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Thank you to all the artists who entered the awards. -

Gladys Nicholls: an Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-War Victoria

Gladys Nicholls: An Urban Aboriginal Leader in Post-war Victoria Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: Gladys Nicholls was an Aboriginal activist in mid-20 th century Victoria who made significant contributions to the development of support networks for the expanding urban Aboriginal community of inner-city Melbourne. She was a key member of a talented group of Indigenous Australians, including her husband Pastor Doug Nicholls, who worked at a local, state and national level to improve the economic wellbeing and civil rights of their people, including for the 1967 Referendum. Those who knew her remember her determined personality, her political intelligence and her unrelenting commitment to building a better future for Aboriginal people. Keywords: Aboriginal women, Aboriginal activism, Gladys Nicholls, Pastor Doug Nicholls, assimilation, Victorian Aborigines Advancement League, 1967 Referendum Gladys Nicholls (1906–1981) was an Indigenous leader who was significant from the 1940s to the 1970s, first, in action to improve conditions for Aboriginal people in Melbourne and second, in grassroots activism for Indigenous rights across Australia. When the Victorian government inscribed her name on the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll in 2008, the citation prepared by historian Richard Broome read as follows: ‘Lady Gladys Nicholls was an inspiration to Indigenous People, being a role model for young women, a leader in advocacy for the rights of Indigenous people as well as a tireless contributor to the community’. 1 Her leadership was marked by strong collaboration and co-operation with like-minded women and men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who were at the forefront of Indigenous reform, including her prominent husband, Pastor (later Sir) Doug Nicholls.