CLASS ACTIONS and the LIMITS of RECOVERY: the GLASS JAW of JUSTICE Part 1 of 2 by David J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1982 Delorean DMC-12

This is the seventh in 1982 DELOREAN a series of articles on “Cars we have DMC-12 photographed and loved.” By William Horton 1982 DeLorean DMC-12 CONTENTS John Zachary DeLorean ........................................................................... 4 DMC a financial drama ............................................................................ 5 Development, innovation, evolution, and variations .......................... 6 Z Tavio? .................................................................................................. 6 First prototype. ...................................................................................... 6 Lotus hired to re-engineer. .................................................................. 7 Compromises hobble performance. ................................................... 7 Continuous evolution, not model-year madness ............................. 8 Variants. .................................................................................................. 8 Manufacturing facility. ............................................................................. 9 Not an overwhelming success. ............................................................... 9 DMC is dead. Long live DMC. .............................................................. 11 Back to the Future. .................................................................................. 12 A Specimen of the Species ..................................................................... 13 Facts and figures .................................................................................... -

The History of Delorean DMC-12

The History of The DeLorean DMC-12 Delorean Introduction The DeLorean DMC-12 is a two-seater sports car that was manufactured by the DeLorean Motor Company (DMC) for the US market from 1981 to 1982. It featured gull-wing doors with a fiberglass underbody to which non-structural brushed stainless steel panels were affixed. Manufactured in Northern Ireland it is most commonly known simply as the DeLorean, as it was the only model ever produced by the company. The first prototype appeared in March 1976, and production officially began in 1981 (with the first DMC-12 rolling off the production line on January 21) at the DMC factory in Dunmurry, Northern Ireland. Over nine thousand DMC-12s were made before production stopped in December 1982. Today, about 6,500 DeLorean Motor Cars are believed to still exist. It is perhaps best remembered when it shot to worldwide fame in the Back to the Future movie trilogy starring Michael J Fox and Christopher Lloyd. The car was transformed into a time machine by the eccentric scientist Doctor Emmett L. Brown - the company had ceased to exist before the first movie was ever made in 1985. DeLorean History In October 1976, the first prototype DeLorean DMC-12 was completed by William T. Collins chief engineer and designer (formerly chief engineer at Pontiac). Originally, the car's rear- mounted power plant was to be a Citroën Wankel rotary engine, but was replaced with a French-designed and produced PRV (Peugeot-Renault-Volvo) fuel injected V-6 because of the poor fuel economy from the rotary engine, an important issue at a time of world-wide fuel shortages. -

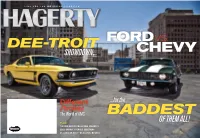

Showdown ... of Them All!

FUEL FOR THE MOTORING LIFESTYLE Dee-troit Ford vs. showdown ... CHevy Fall 2011 $4.95 U.S.a. | Canada Different ... for the Strokes The World of AMC baddest Plus: of them all! THE ODD ART OF COLLECTING CONCEPTS COOL GARAGE STORAGE SOLUTIONS ST. LOUIS OR BUST—IN A LOTUS, NO LESS a word from mckeel FordFord vs.vs. Chevy Chevy in the Driver’s seat editoriAl stAFF Executive Publisher McKEEL Hagerty Publisher RoB SASS Associate Publisher Jonathan A. Stein Senior Publishing Advisor Greg Stropes Executive Editor JERRy Burton Managing Editor nAdInE SCodELLARo Art director/designer Todd Kraemer Copy Editor SHEILA WALSH dETTLoFF Art Production Manager JoE FERRARo Although McKeel Creative director LAURA RoGERS hagerty spends as Editorial director dAn GRAnTHAM much time as possible in the driver’s seat, he Publishing stAFF director of Publishing Angelo ACoRd found time to sit on a Publication Manager Danielle PoissanT panel of notable auto Production Manager Lynn Sarosik MAGES editors and writers y I Ad Sales Coordinator KIM PoWERS to make his picks in ETT our Ford vs. Chevy Contributors Carl Bomstead, BoB Butz, WAynE on, G showdown. rt CarinI, KEn GRoss, DavE KInnEy, Stefan Lombard, jeff peek, JoHn L. Stein n Mo TEPHE Advertising stAFF S director of Ad Sales East Coast Sales office ToM Krempel, 586-558-4502 [email protected] Central/West Coast Sales office Lisa Kollander, 952-974-3880 Fun with cars [email protected] Anyone who’s read at least one issue of Hagerty magazine realizes that we subscribe to the notion that the old car hobby is supposed to be fun — fun in the sense that we enjoy using our cars from time to time and that we have a good time poking fun both at ourselves and the foibles of our beloved old cars. -

Rumbler Humor

LOOKING TOWARDS NEW CHEVROLET LOOKING TOWARDS 1 THE FUTURE 19 CAMARO ZL1 Club President can hit 60 MPH THE FUTURE "Skovy" in 1st Gear! 2 ACTIVE MEMBERS RUMBLER HUMOR BLACK TOP TOUR 1956 Chevy 20 3 REPORT Convertible Pictures from the run 6th Annual Car Show RUMBLER MINISTRY 21 at Don Wilhelm Inc 7 Pastor Scott Block Pictures & Results AROUND MILL HILL from 9 MOVIE the Show RUMBLER HUMOR DeepWater Horizon AROUND MILL HILL 24 Homeless Man 10 DINNER 25 SWAP SHOP Spiritwood Resort 27 Upcoming Events Answers from the Test Story & Photos by Skovy FORD BRONCO making 27 your knowledge test 10 slow-speed chase 28 CLUB APPLICATION Well darn it... Winter is just back into lineup around the corner and everybody RING BROTHERS is putting their rides in the 11 announce Impressive warehouses until spring. lineup for SEMA show RUMBLER HUMOR Sorry everybody about the 2 13 Trust month hiatus on the “RUMBLER” FOR OLD CAR magazine and 2 summer 14 and Hollywood Star cookouts this year. enthusiast TEST YOUR Miscommunication on 16 KNOWLEDGE “RUMBLER” advertising and of the most Iconic cars weather issues kept us from made in the USA summer cookouts this year. I PIONEER AUTO promise to be more organized SHOW next year. 18 New items on display P a g e | 2 Well that’s the end of the Don’t be bashful. We are a very Eslick, Larry negative news... now for what’s active organization and want Frueh, Darin positive and fun moving forward. members. It’s only $25.00 for a Gaier, Craig & Johnston, Ruth regular membership & $50.00 if Gehring, Duane & Kathleen For those of you that went on the you want the “RUMBLER” mailed Geisler, David “Blacktop Tour” this year, I have to you. -

No. 18-3333 SALLY DELOREAN

NOT PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT ______________ No. 18-3333 ______________ SALLY DELOREAN, as administratrix for The Estate of John Z. DeLorean Appellant v. DELOREAN MOTOR COMPANY (Texas) ______________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey (D.C. Civ. No. 2-18-cv-08212) District Judge: Honorable Jose L. Linares ______________ Submitted Under Third Circuit L.A.R. 34.1(a) October 21, 2019 ______________ Before: GREENAWAY, JR., PORTER, and COWEN, Circuit Judges. (Opinion Filed: December 5, 2019) ______________ OPINION* _____________ GREENAWAY, JR., Circuit Judge. This case requires that we interpret a Settlement Agreement entered into by Sally DeLorean as administratrix of the Estate of John Z. DeLorean (the “Estate”) and DeLorean Motor Company (Texas) (“DMC Texas”) in the action Estate of DeLorean v. DeLorean Motor Company (Texas), No. 2:14-cv-1146 (D.N.J.). The question presented is whether the Settlement Agreement precludes the Estate’s claims in this action. The District Court found that it did, and the Estate appealed. For the following reasons, we will affirm. BACKGROUND In the 1970s, John Z. DeLorean founded the DeLorean Motor Company (“DMC”). DMC designed, manufactured, and sold an automobile named the DMC 12, which featured gull-wing doors. DMC ceased operations in 1979 and was subsequently dissolved through bankruptcy proceedings. * This disposition is not an opinion of the full Court and pursuant to I.O.P. 5.7 does not constitute binding precedent. 2 A. The Universal Agreement DMC may have gone defunct decades ago, but the DeLorean automobile remains culturally relevant in large measure due to Universal Pictures’s popular “Back to the Future” film series, which prominently features the DeLorean automobile. -

The Rise of China's Luxury Automotive Industry

Heritage with a High Price Tag: The Rise of China’s Luxury Automotive Industry Sydney Ella Smith AMES 499S Honors Thesis in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Durham, North Carolina April 2018 Guo-Juin Hong Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Supervising Professor Leo Ching Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Committee Member Shai Ginsburg Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Committee Member Heritage with a High Price Tag: The Rise of China’s Luxury Automotive Industry Sydney Ella Smith, B.A. Duke University, 2018 Supervisor: Guo-Juin Hong TABLE OF CONTENTS Author’s Note ...........................................................................................................ii Introduction: For Automobiles, Failure Builds Resiliency ......................................1 Chapter 1: Strategy Perspectives on the Chinese Automotive Industry ...................9 Michael Porter’s “Five-Forces-Model” ........................................................12 Michael Porter’s “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition” ........23 Chapter 2: Luxury Among the Nouveau Riche: The Chinese Tuhao (土豪) .........32 What is Luxury? ...........................................................................................34 Who Buys Luxury? ......................................................................................39 Evolving Trends in Luxury ..........................................................................45 Conclusion: Cars with Chinese Characteristics ......................................................49 -

School Refurbishment Brightens Future by Staff Sgt

Multi-National Division – Baghdad “First Team.....Team First” Monday, October 19, 2009 School refurbishment brightens future By Staff Sgt. Mark Burrell The project included According to Simpson, more willing to show up to MND-B PAO cleaning up debris, painting the Nassir Wa Salem area school.” BAGHDAD — Children the building, adding electric- council and U.S. force from According to Kalid, one of laughed and talked excitedly ity and fixing the plumbing 4th Stryker Brigade Combat the most important renova- throughout the re-opening for the 128 local area chil- Team, 2nd Infantry Division tions was the bathrooms. In ceremony of the Zuhair Bin dren that attend the school, worked closely to rebuild the the past, the students didn’t Abysulma Primary School in explained Simpson, who is one-story schoolhouse and have proper facilities, mak- the Zaidon area of western assigned to the 422nd Civil provide desks and chairs for ing the school an uncomfort- Baghdad, Oct. 15. Affairs Battalion. the faculty and students to able place to spend the school The $67,000 refurbishment “Before, the school was foster a better learning envi- year. project was a joint effort be- dark; it had lots of trash and ronment. “Whenever students are tween U.S. troops and the lo- even broken glass. Now it’s “This is a very impor- happy and comfortable, it is cal government that came to brighter and the students are tant day and we feel very easier for the teacher to teach fruition after three months much happier, have more en- happy because everything the students,” continued Ka- of hard work, said Navy Lt. -

BMW 333I & 325Is

DELOREAN DMC-12 PORSCHE 924 JAGUAR SS100 R47.00 incl VAT • December/January 2015/16 CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF THE BMW 3 SERIES WITH SA’S LEGENDARY BMW 333i & 325iS ISOTTA FRASCHINI ASTON MARTIN DB6 COACHBUILT ITALIAN WITH TOP SECRETS FROM A HISTORICAL TWISTS AND TURNS RESTORATION AGENT SANI PASS BY BEETLE | BIRKIN TEST | INTERNATIONAL BENTLEY TOUR FOR BOOKINGS 0861 11 9000 proteahotels.com IF PETROL RUNS IN YOUR VEINS, THIS IS A SIREN CALL TO THE OPEN ROAD... TO BOOK THIS & MANY MORE GREAT MOTORING SPECIALS VISIT proteahotels.com GEAR UP FOR THE GEORGE OLD CAR SHOW DATE: 12-14 FEBRUARY 2016 George lies in the heart of the Garden Route at the foot of the Outeniqua Mountains. This sleepy town comes to life with the beautiful noise of purring engines once a year at one of the biggest Classic Car events in South Africa, the George Old Car Show. We invite you to be our GUEST with these all inclusive value for money packages. PROTEA HOTEL KING GEORGE PROTEA HOTEL OUTENIQUA This Hotel offers you luxury 4-star accommodation with a Enjoy the hospitality in this national Heritage site with fantastic package deal including: packages including: Car wash on arrival. Full English Breakfast every morning. Car wash on arrival. Full English Breakfast every morning. Shuttle to the show with a weekend pass. VIP access to the Shuttle to the show with a weekend pass. VIP access to the Protea Hotels VIP hospitality Marquee overlooking the show. Protea Hotels VIP hospitality Marquee overlooking the show. R1090 R795 per person sharing per person sharing Terms and conditions apply. -

In Transitioning Ulevs to Market by Gavin DJ Harper 2014

The role of Business Model Innovation: in transitioning ULEVs To Market by Gavin D. J. Harper BSc. (Hons) BEng. (Hons) MSc. MSc. MSc. MIET A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cardiff University Logistics and Operations Management Section of Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University 2014 Contents CONTENTS II CANDIDATE’S DECLARATIONS XII LIST OF FIGURES XIII LIST OF TABLES XVIII LIST OF EQUATIONS XIX LIST OF BUSINESS MODEL CANVASES XIX LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS XX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS XXIV ABSTRACT XXVII CHAPTER 1: 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The Drive towards Sustainable Mobility 1 1.1.1 Sustainability 2 1.1.1.1 Archetypes of Sustainability 4 1.1.1.2 What do we seek to sustain? 5 1.1.1.3 Sustainable Development 6 1.1.1.4 Strategising for Sustainable Development 8 1.1.1.5 The Environmental Footprint of Motor Vehicles 10 1.1.1.6 Resource Scarcity & Peak Oil 12 1.1.1.7 Climate Change & Automobility 13 1.1.1.8 Stern’s Framing of Climate Change 16 1.1.1.9 Accounting for Development 17 1.1.1.10 Population, Development & The International Context 19 1.1.1.11 Sustainable Mobility: A Wicked Problem? 21 1.1.1.12 A Systems View of Sustainability & Automobility 22 1.1.2 Sustainable Consumption & Production 26 1.1.2.1 Mobility: A Priority SCP Sector 26 1.1.2.2 Situating the Car In A Sustainable Transport Hierarchy 27 1.1.2.3 The Role of Vehicle Consumers 29 1.1.2.4 Are Consumers To Blame? 30 1.1.2.5 The Car Industry: Engineering for Consumption? 31 1.1.2.6 ULEVs: Consuming Less? 32 ~ ii ~ 1.1.3 -

The Geographical Factors on the Failure of Bricklin Canada Limited

THE GEOGRAPHICAL FACTORS ON THE FAILURE OF BRICKLIN CANADA LIMITED BY SHAWN M. WILLIAMSON A Research Paper Submitted to the Department of Geography in Fulfilment of the Requirements of Geography 4C6 McMaster University April 1991 ABSTRACT This research paper investigates the factors on business failure in the Maritime region of Canada via a sample study of Bricklin Canada Ltd. This sample illustrates· the effects of regionalism and geographic location on the manufacturing industry. This company's failure will be examined as how it arose from reasons including geographic isolation, regional disparities, externalities, scale economies and external forces. A study of this particular industrial failure will lend insights regarding the needs of future regional policy. Although businesses from these marginalized regions of Canada have realized success, there are still a great many steps yet to take. A means must be found to re introduce a self-sustaining economy to these regionalized areas of Canada where it is lacking. i i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity ,to thank all those who have contributed to this paper. My sincere thanks to Dr. Liaw, my staff advisor, who took the time and effort to guide me through my work in the past year. I would also like to thank the following gentlemen for their assistance, expertise and time. Dr. Ralph Matthews of the McMaster University Sociology Department for being my "East Coast Correspondent". Dr. Archie Hamielec of the McMaster University Chemical Engineering Department for ·being my witness and expert on the Bricklin situation. Marvin Ryder of the McMaster University Business Department for his insights and information on the Canadian automotive industry. -

Six Theses on Saving the Planet

Six Theses on Saving the Planet By Richard Smith From the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, workers, trade unionists, radicals, and socialists have fought against the worst depredations of capitalist development: intensifying exploitation, increasing social polarization, persistent racism and sexism, deteriorating work- place health and safety conditions, environmental ravages, and relentless efforts to suppress democratic political gains under the iron heel of capital. Yet, even as we fight to hold onto the few gains we’ve made, today, the engine of global capitalist development has thrown up a new and unprecedented threat, an existential threat to our very survival as a species. The engine of economic development that has brought unprecedented material gains, and revolutionized human life, now threatens to develop us to death, to drive us over the cliff to extinction, along with numberless other species. Excepting the threat of nuclear war, the runaway locomotive yst w s em p e s n s o l s a s i s b o i l p o it r ie s & p of capitalist development is the greatest peril humanity has ever faced. This essay addresses this threat and contends that there is no possible solution to our exis- tential crisis within the framework of any conceivable capitalism. It suggests that, impossible as this may seem at present, only a revolutionary overthrow of the existing social order, and the institution of a global eco-socialist democracy, has a chance of preventing global ecological collapse and perhaps even our own extinc- tion. By “global eco-socialist democracy,” I mean a world economy composed of communities and nations of self-governing, associated producer-consumers, cooperatively managing their mostly planned, mostly publicly-owned, and glob- ally coordinated economies in the interests of the common good and future needs of humanity, while leaving aside ample resources for the other species with which we share this small blue planet to live out their lives to the full. -

John Delorean

SMOKE SIGNALS The Official Publication of the ANKOKAS Region AACA March/ April 2016 Volume 53, Issue 2 In This Month’s Issue: Prez Sez......................1 News & Events............2 Minutes From Previous We seem to be off to a good start for arranged for someone to babysit the cars while Meetings.....................3 2016 and let’s keep the old ball rolling. If you have lunch. Calendar......................4 you missed our February breakfast meeting, May 14th is our tour to the Philadelphia Member Profile...........5 shame on you. The food was good and the Masonic Lodge and lunch. Don’t miss this one. Roadside Ramblings...7 fellowship even better. Maybe we will do The AACA Eastern Division spring meet is in The Car is The Star.....8 another in the fall. Vineland May 21st. If you have not been to a The Men Behind the We have a number of things going on division meet in a while, here is a chance right Cars..........................11 in the next few months, so go get the in your back yard. It is hosted by the South Fun & Trivia...............12 calendar off the fridge and mark the dates Jersey Region. We are waiting to hear if they Letter from the of Ankokas activities in big bold letters. Too want Ankokas help. Editors.......................12 many people tell me they “forgot”. Put the date of June 1 on your calendar Marketplace..............13 Write it down on the calendar. I as we will be touring the backstage promised you we would have of the Atlantic City Boardwalk pipe something going on every organ at 10 am.