Architecture During the Great Depression: a Study of Building Trends in Charlotte, North Carolina”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

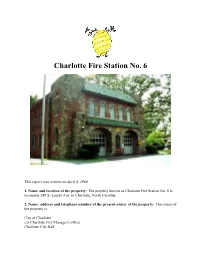

Charlotte Fire Station No. 6

Charlotte Fire Station No. 6 This report was written on April 4, 1988 1. Name and location of the property: The property known as Charlotte Fire Station No. 6 is located at 249 S. Laurel Ave. in Charlotte, North Carolina. 2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is: City of Charlotte c/o Charlotte City Manager's office Charlotte City Hall 600 E. Trade St. Charlotte, N.C. 28202 Telephone: 704/336-2241 The tenant of the building is the Charlotte Fire Department. For information contact: Mr. Robert Ellison Assistant Chief for Administration Charlotte Fire Department 125 S. Davidson St. Charlotte, N.C. 28202 Telephone: 704/336-2051 3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property. 4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property. Click on the map to browse 5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent reference to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg Deed Book 717, Page 361. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 155-034-17. 6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman, Ph.D. 7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Joseph Schuchman. 8. Documentation of and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation-set forth in N.C.G.S. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

Industry, Transportation and Education

Industry, Transportation and Education The New South Development of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County Prepared by Sarah A. Woodard and Sherry Joines Wyatt David E, Gall, AIA, Architect September 2001 Introduction Purpose The primary objective of this report is to document and analyze the remaining, intact, early twentieth-century industrial and school buildings in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County and develop relevant contexts and registration requirements that will enable the Charlotte- Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission and the North Carolina Historic Preservation Office to evaluate the individual significance of these building types. Limits and Philosophy The survey and this report focus on two specific building types: industrial buildings and schools. Several of these buildings have already been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Nevertheless, the increase in rehabilitation projects involving buildings of these types has necessitated the creation of contexts and registration requirements to facilitate their evaluation for National Register eligibility. The period of study was from the earliest resources, dating to the late nineteenth century, until c.1945 reflecting the large number of schools and industrial buildings recorded during the survey of Modernist resources in Charlotte, 1945 - 1965 (prepared by these authors in 2000). Developmental History From Settlement to the Civil War White settlers arrived in the Piedmont region of North Carolina beginning in the 1740s and Mecklenburg County was carved from Anson County in 1762. Charlotte, the settlement incorporated as the Mecklenburg county seat in 1768, was established primarily by Scots-Irish Presbyterians at the intersection of two Native American trade routes. These two routes were the Great Wagon Road leading from Pennsylvania and a trail that connected the backcountry of North and South Carolina with Charleston. -

History of Mecklenburg County and the City Of

2 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL THE COLLECTION OF NORTH CAROLINIANA C971.60 T66m v. c.2 UNIVERSITY OF N.C. AT CHAPEL HILL 00015565808 This book is due on the last date stamped below unless recalled sooner. It may be renewed only once and must be brought to the North Carolina Collection for renewal. —H 1979 <M*f a 2288 *» 1-> .._ ' < JoJ Form No. A- 369 BRITISH MAP OF MECKLENBURG IN 1780. History of Mecklenburg County AND The City of Charlotte From 1740 to 1903. BY D. A. TOMPKINS, Author of Cotton and Cotton Oil; Cotton Mill, Commercial Features ; Cotton Values in Tex- Fabrics Cotton Mill, tile ; Processes and Calculations ; and American Commerce, Its Expansion. Charlotte, N. C, 1903. VOLUME TWO—APPENDIX. CHARLOTTE, N. C: Observer Printing House. 1903. COPYRIGHT, 1904. BY I). \. TOMPKINS. EXPLANATION. This history is published in two volumes. The first volume contains the simple narrative, and the second is in the nature of an appendix, containing- ample discussions of important events, a collection of biographies and many official docu- ments justifying and verifying- the statements in this volume. At the end of each chapter is given the sources of the in- formation therein contained, and at the end of each volume is an index. PREFACE. One of the rarest exceptions in literature is a production devoid of personal feeling. Few indeed are the men, who, realizing that the responsibility for their writings will be for them alone to bear, will not utilize the advantage for the promulgation of things as they would like them to be. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2004

National Register of Historic Places 2004 Weekly Lists January 2, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 9, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................. 5 January 16, 2004 ........................................................................................................................................... 8 January 23, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 10 January 30, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 February 6, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 19 February 13, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 23 February 20, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 25 February 27, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 29 March 5, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................ -

North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places As of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by County

North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places as of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by county. Listings with an http:// address have an online PDF of the nomination. Click address to view the PDF. Text is searchable in all PDFs insofar as possible with scans made from old photocopies. Multiple Property Documentation Form PDFs are now available at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/MPDF-PDFs.pdf Date shown is date listed in the National Register. Alamance County Alamance Battleground State Historic Site (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0001.pdf Alamance County Courthouse (Graham ) 5/10/1979 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0008.pdf Alamance Hotel (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0613.pdf Alamance Mill Village Historic District (Alamance ) 8/16/2007 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0537.pdf Allen House (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0002.pdf Altamahaw Mill Office (Altamahaw ) 11/20/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0486.pdf (former) Atlantic Bank and Trust Company Building (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0630.pdf Bellemont Mill Village Historic District (Bellemont ) 7/1/1987 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0040.pdf Beverly Hills Historic District (Burlington ) 8/5/2009 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0694.pdf Hiram Braxton House (Snow Camp vicinity) 11/22/1993 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0058.pdf Charles F. and Howard Cates Farm (Mebane vicinity) 9/24/2001 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0326.pdf -

The History of Mecklenburg County 1740 1900

History, NC, Mecklenburg, 1740 to 1900 THE HISTORY Of Mecklenburg County From 1740 to 1900. BY. J. B. ALEXANDER, M. D., Charlotte. N. C. 1902. CHARLOTTE. N. C.: OBSERVER PRINTING HOUSE. 1902. Page 1 of 355 History, NC, Mecklenburg, 1740 to 1900 COPYRIGHT 1902 BY J. B. ALEXANDER, M. D. Page 2 of 355 History, NC, Mecklenburg, 1740 to 1900 Table of Contents Preface...................................................................8 CHAPTER I...................................................................11 Early Settlement.........................................................11 Early Recollections of Charlotte.........................................13 Physicians...............................................................15 CHAPTER II..................................................................20 Monument To Signers......................................................20 May 20, 1775.............................................................21 Instructions for the delegates of Mecklenburg county...................27 A Historical Fact Not Generally Known..................................36 CHAPTER III.................................................................40 The War of 1812-1814.....................................................40 Seventh Company........................................................40 Eighth Company.........................................................41 Ninth Company..........................................................42 Muster Roll............................................................43 -

Fire Station Number 8

Survey and Research Report On Fire Station Number Eight 1. Name And Location Of The Property. The Former Charlotte Fire Station Number Eight is located at 1201 The Plaza in Charlotte, N.C. 2. Name And Address Of The Present Owner Of The Property. City of Charlotte c/o Real Estate Division 600 East Fourth Street Charlotte, N.C. 28202 1 3. Representative Photographs Of The Property. The report contains representative photographs of the property. 4. Map Depicting The Location Of The Property. 0 0.01250.025 0.05 Miles Charlotte Fire Station Number 8 2 5. Current Deed Book Reference To The Property. The current deed to the property is not listed. The tax parcel number of the property is 08117627. 6. A Brief Historic Sketch Of The Property. The report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. Dan L. Morrill. 7. A Brief Physical Description Of The Property. The report contains a brief physical description of the property prepared by Stewart Gray. 8. Documentation Of Why And In What Ways The Property Meets The Criteria For Designation Set Forth In N.C.G.S. 160A-400.5. a. Special Significance In Terms Of Its History, Architecture, And/Or Cultural Importance. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission judges that Charlotte Fire Station Number Eight possesses special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) The architect of Charlotte Fire Station Number Eight was Marion Rossiter “Steve” Marsh (1893- 1977), who practiced architecture in Charlotte from 1922 until his retirement in 1964. -

Hr40189-Lg-33 (03/01)

H.R. 323 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA Mar 13, 2017 SESSION 2017 HOUSE PRINCIPAL CLERK H D HOUSE SIMPLE RESOLUTION DRHR40189-LG-33 (03/01) Sponsors: Representative Clampitt. Referred to: 1 A HOUSE RESOLUTION HONORING THE LIFE AND MEMORY OF HOWARD "BUDDY" 2 WILSON. 3 Whereas, Howard "Buddy" Wilson was born on July 24, 1934, in Charlotte, North 4 Carolina; and 5 Whereas, during his childhood, Buddy was a Boy Scout and achieved the rank of Eagle 6 Scout; and 7 Whereas, Buddy graduated from Harding High School in 1952, then enlisted in the 8 United States Navy, where he served until 1955, receiving an Honorable Discharge and earning 9 the National Defense Service Medal; and 10 Whereas, after serving in the Navy, Buddy returned to Charlotte, where he became a 11 firefighter with the Charlotte Fire Department (CFD) in 1957; and 12 Whereas, originally assigned to Engine Company 7, Buddy received several 13 promotions and attained the rank of Captain by 1963; and 14 Whereas, Buddy became a training officer with the Palmer Fire School, and his duties 15 included serving as a Recruit Training Officer; a North Carolina Fire Service Instructor; an 16 instructor for Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC) in topics related to the fire service, 17 first aid, CPR, mountaineering, and rescue; and an arson investigator; and 18 Whereas, while a training officer, Buddy earned an A.A.S. degree in Fire Science 19 Technology at CPCC in one of the first graduating classes; attained numerous certifications in 20 areas such as CPR, fire investigation, -

ELIZABETH NEIGHBORHOOD Change and Continuity in Charlotte's Second Streetcar Suburb by Dr

THE ELIZABETH NEIGHBORHOOD Change and Continuity in Charlotte's Second Streetcar Suburb by Dr. Thomas W. Hanchett The Elizabeth neighborhood on Charlotte's east side is the city's second oldest streetcar suburb. It was begun in 1891 along what is now Elizabeth Avenue, an easterly extension of East Trade Street which was one of the city's major business and residential streets. The present-day neighborhood includes five separate early subdivisions developed along the Elizabeth Avenue-Hawthorne Lane-Seventh Street trolley line and the Central Avenue trolley line by the 1920s. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, before neighboring Myers Park developed as Charlotte's elite residential area, the tree-shaded main boulevards of Elizabeth were among the city's most fashionable suburban addresses for business and civic leaders. The early residential development of Elizabeth is but half its history, however. More than any other early Charlotte suburb, Elizabeth has felt the effects of the automobile as it has transformed the city. Charlotte's hospitals left the central business district for suburban Elizabeth beginning in the late teens, and now the neighborhood is the site of two of the city's three general hospitals, and two smaller medical facilities are nearby. Small neighborhood shopping clusters began to form in the twenties. By the 1950s every one of Charlotte's principal east-west traffic arteries sliced through the neighborhood. During the next two decades a private business college and one of North Carolina's largest community colleges built their campuses in Elizabeth, and a 1960s zoning plan encouraged extensive demolition of houses to allow new office development. -

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2017 H 1 House Resolution 323

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2017 H 1 HOUSE RESOLUTION 323 Sponsors: Representative Clampitt. For a complete list of sponsors, refer to the North Carolina General Assembly web site. Referred to: Rules, Calendar, and Operations of the House March 14, 2017 1 A HOUSE RESOLUTION HONORING THE LIFE AND MEMORY OF HOWARD "BUDDY" 2 WILSON. 3 Whereas, Howard "Buddy" Wilson was born on July 24, 1934, in Charlotte, North 4 Carolina; and 5 Whereas, during his childhood, Buddy was a Boy Scout and achieved the rank of Eagle 6 Scout; and 7 Whereas, Buddy graduated from Harding High School in 1952, then enlisted in the 8 United States Navy, where he served until 1955, receiving an Honorable Discharge and earning 9 the National Defense Service Medal; and 10 Whereas, after serving in the Navy, Buddy returned to Charlotte, where he became a 11 firefighter with the Charlotte Fire Department (CFD) in 1957; and 12 Whereas, originally assigned to Engine Company 7, Buddy received several 13 promotions and attained the rank of Captain by 1963; and 14 Whereas, Buddy became a training officer with the Palmer Fire School, and his duties 15 included serving as a Recruit Training Officer; a North Carolina Fire Service Instructor; an 16 instructor for Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC) in topics related to the fire service, 17 first aid, CPR, mountaineering, and rescue; and an arson investigator; and 18 Whereas, while a training officer, Buddy earned an A.A.S. degree in Fire Science 19 Technology at CPCC in one of the first graduating classes; attained -

Notes About Scotch-Irish and German Settlers in Virginia and the Carolinas

Notes about Scotch-Irish and German Settlers in Virginia and the Carolinas Copyright © 2000–2009 by William Lee Anderson III. All rights reserved. Scotch-Irish and German Settlers in Virginia and the Carolinas Introduction During the 1700s many Scotch-Irish and German immigrants arrived in America. They and their children settled parts of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Today, most of their descendants never think about their heritage. Most live in the present, are working on real-life problems, or planning their future. That attitude was shared by their ancestor immigrants 250 years ago. Nonetheless, I suspect most descendants have at least wondered what the word Scotch-Irish means. All my life, I have heard various facts, but never understood how they fit together. Some facts appeared contradictory. So, I investigated, and discovered a colorful story that far exceeded my expectations. My principal objectives were to: Understand certain comments made by grandparents and other relatives over 40 years ago. Understand the confusing adjective Scotch-Irish. Understand the confusing cultural icons of bagpipes, kilts, Celtic whistles, etc. Understand the history of Moravian, Lutheran, Mennonite, Amish, Dunkards, Presbyterian, Puritanism, Huguenot, Quaker, Methodist, Congregational, and Baptist denominations that have churches in the Carolinas. Understand why and when surnames became common. Understand ancestor Margaret Moore‘s recollections of the Siege of Londonderry in 1689. Understand motivations of Scotch-Irish and German immigrants during the 1700s and terms of their Carolina land grants. Understand relations between early Carolina immigrants and Native Americans. Understand why Scotland‘s heroine Flora Macdonald came to live in North Carolina in 1774.