ASEAN's Future and Asian Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

The Effects of ASEAN Free Trade Are to Its Members

Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 21, November 2006 Determinants of AFTA Members’ Trade Flows and Potential for Trade Diversion By Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong* *Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong are Research Assistant at the Department of Economics Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Teaching Assistant at the Faculty of Economics, University of Indonesia, The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CSIS, ARTNeT members, partners and the United Nations. This study was conducted as part of the Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) initiative, aimed at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The technical support of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific is gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors. The authors may be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected] The Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) aims at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. The ARTNeT Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about trade issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. ARTNeT working papers are available online at: www.artnetontrade.org. -

Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and East Asian Exchange Rate Cooperation

Much Ado about Nothing? Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and East Asian Exchange Rate Cooperation Much Ado about Nothing? Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and East Asian Exchange Rate Cooperation Wolf HASSDORF ※ Abstract This article asks why the creation by the ASEAN+3 countries of a common reserve pool, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM) of 2010, has not brought about a decisive breakthrough towards regional exchange-rate cooperation of Japan and China. With the global financial crisis acting as catalyst, optimists expected CMIM to facilitate agreement of the two East Asian powers on an Asian Currency Unit and Asian Monetary Fund-style institution, but nothing of relevance materialised. The article analyses this disappointing outcome by criticising the neo-functionalist optimistic view from both a realist and liberal intergovernmentalist perspective. It concludes that the lack of progress in Sino-Japanese regional currency cooperation can be explained by combining realist and intergovernmentalist analysis: regional rivalry of China and Japan, driven by ‘high politics’ national security concerns and diverging ‘low politics’ policy preferences rooted in incompatible domestic economic policy- making regimes, is the key reason for lack of progress. Key words: East Asian Regionalism, Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization, Sino-Japanese cooperation, neo-functionalism, liberal institutionalism 1. Introduction This paper asks why the creation by the ASEAN+3 (APT)1 countries of a common reserve pool to provide financial assistance to East Asian nations in case ※ Associate Professor, Ritsumeikan University, College of International Relations (hassdorf@ fc.ritsumei.ac.jp) 1. For the purpose of this paper I define East Asia as the ASEAN+3 grouping (APT), that is the 10 ASEAN countries plus China, Japan and South Korea. -

The Role of the Bric in Africa's Development

Journal for Contemporary History 41(1) / Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis 41(1): 80-102 © UV/UFS • ISSN 0258-2422 / e-ISSN 2415-0509 http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150509/jch.v41i1.5 THE ROLE OF THE BRIC IN AFRICA’S DEVELOPMENT: DRIVERS AND STRATEGIES Mills Soko1 and Mzukisi Qobo2 Abstract National interest still trumps friendship in international relations. The notions of solidarity that were popular among developing countries in the 1950s and the 1960s have no resonance in 21st century diplomacy, which is largely driven by commercial considerations. Many developing countries still view the advent of rising powers – some of whom were part of the Third World movement that arrayed itself to counter imperialism – as offering promise for development progress. Taking an analytic assessment of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries’ role in Africa’s development, this article argues that such hopes are misguided. BRIC countries are not primarily driven by Africa’s development concerns, but are seeking to fulfil their own commercial interests, as well as use Africa as an avenue for shoring up their international legitimacy and credibility. The article arrives at this conclusion by examining how each of the BRIC countries implements its commercial and diplomatic strategies on the African continent. South Africa is excluded from this analysis as the focus of the article is on how the non-African members of the BRICS formation pursue their diplomatic and commercial strategies on the African continent. Keywords: BRIC countries; drivers; development; strategies; Africa. Sleutelwoorde: BRIC-lande; dryfvere; ontwikkeling; strategieë; Afrika. 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1995, the African continent has registered rapid economic growth and development against the backdrop of both a commodities’ boom and expanding investment in a diverse range of sectors, from natural-resourced based industries to wholesale, retail, trade, telecommunications and manufacturing. -

Download the Full Chapter » (PDF)

37 CHAPTER 2 ASSESSING REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS’ WORK IN DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT his chapter looks at one group of important but little-studied actors in disaster risk management (DRM): regional organizations.171 Although regional mechanisms are Tplaying increasingly important roles in disasters, there has been remarkably little research on their role in disaster risk management. In fact, there are few published studies about the relative strengths and weaknesses of regional bodies, much less comparisons of their range of activities or effectiveness in DRM.172 A recent study carried out by the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement sought to address this gap by providing some basic information about the work of more than 30 regional organizations involved in disaster risk management and by drawing some comparisons and generalizations about the work of thirteen of these organizations through the use of 17 indicators of effectiveness.173 This chapter provides a summary of some of that research. SECTION 1 Introduction and Methodology: Why a Focus on Regions? Since the 1950s when European regional integration seemed to offer prospects not only for the region’s post-war recovery, but also for lasting peace and security between former enemies, regional organizations have been growing in number and scope. They have 171 There has been a trend to move away from a rigid dichotomy between activities intended to reduce risk/ prepare for disasters and those associated with emergency relief and reconstruction. Thus the term “disaster risk management” (DRM) is used as the overarching concept in this study. However, as the dichotomy between pre-disaster and post-disaster activities is still prevalent in international institutions, international agreements and frameworks, government institutions and regional institutions, the disaster risk reduction (DRR) is also used as a catch-all term for pre-disaster activities while the term disaster management (DM) refers to all post- disaster activities. -

Forced to Go East? Iran’S Foreign Policy Outlook and the Role of Russia, China and India Azadeh Zamirirad (Ed.)

Working Paper SWP Working Papers are online publications within the purview of the respective Research Division. Unlike SWP Research Papers and SWP Comments, they are not reviewed by the Institute. MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA DIVISION | WP NR. 01, APRIL 2020 Forced to Go East? Iran’s Foreign Policy Outlook and the Role of Russia, China and India Azadeh Zamirirad (ed.) Contents Introduction 3 Azadeh Zamirirad Iran’s Energy Industry: Going East? 6 David Ramin Jalilvand Russia: Iran’s Ambivalent Partner 13 Nikolay Kozhanov Iran and China: Ideational Nexus Across the Geography of the BRI 18 Mohammadbagher Forough Indo-Iranian Relations and the Role of External Actors 23 P R Kumaraswamy Opportunities and Challenges in Iran-India Relations 28 Ja’far Haghpanah and Dalileh Rahimi Ashtiani The European Pillar of Iran’s East-West Strategy 33 Sanam Vakil Implications of Tehran’s Look to the East Policy for EU-Iran Relations 38 Cornelius Adebahr 2 Introduction Azadeh Zamirirad The covid-19 outbreak has revived a foreign policy debate in Iran on how much the Dr Azadeh Zamirirad is Dep- country can and should rely on partners like China or Russia. Critics have blamed uty Head of the Middle East and Africa Division at SWP in an overdependence on Beijing for the hesitation of Iranian authorities to halt flights Berlin. from and to China—a decision many believe to have contributed to the severe spread of the virus in the country. Others point to economic necessities given the © Stiftung Wissenschaft drastic sanctions regime that has been imposed on the Islamic Republic by the US und Politik, 2020 All rights reserved. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

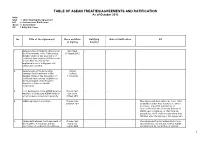

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Brics Versus Mortar? Winning at M&A in Emerging Markets

BRICs Versus Mortar? WINNING AT M&A IN EMERGING MARKETS The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) is a global management consulting firm and the world’s leading advisor on business strategy. We partner with clients from the private, public, and not-for- profit sectors in all regions to identify their highest-value opportunities, address their most critical challenges, and transform their enterprises. Our customized approach combines deep in sight into the dynamics of companies and markets with close collaboration at all levels of the client organization. This ensures that our clients achieve sustainable compet itive advantage, build more capable organizations, and secure lasting results. Founded in 1963, BCG is a private company with 78 offices in 43 countries. For more information, please visit bcg.com. BRICs VeRsus MoRtaR? WINNING AT M&A IN EMERGING MARKETS JENS KENGELBACH DOminiC C. Klemmer AlexAnDer Roos August 2013 | The Boston Consulting Group Contents 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 THE GLOBAL M&A MARKET ReMAINS IN A DEEP FREEZE Disappointing Results for Public-to-Public Deals Emerging Markets Claim a Growing Share of Deal Flow Key Investing Themes 13 LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE AND MANAGING COMPLEXITY: THE KEYS TO SUPERIOR ReTURNS Serial Acquirers Reap the Rewards of Experience The Virtue of Simplicity 17 A TOUR OF THE BRIC COUNTRIES Brazil Looks to the North Russia Seeks Technology, Resources—and Stability India Aims at Targets of Opportunity China Hunts for Management Know-How—and Access to the Global Business Arena 31 EMERGING THEMES AND ReCOMMENDATIONS 34 Appendix: Selected trAnSActionS, 2012 And 2013 36 FOR FURTHER ReADING 37 NOTE TO THE ReADER 2 | BRICs Versus Mortar? exeCutIVe suMMaRy espite the current worldwide lull in mergers and acquisitions, there’s Dnot much argument that emerging markets will remain a hotbed of M&A activity for some time to come. -

Assessing Investment Policies of Member Countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council

ASSESSING INVESTMENT POLICIES OF MEMBER COUNTRIES OF THE GULF COOPERATION COUNCIL Stocktaking analysis prepared by the MENA-OECD Investment Programme and presented at the Conference entitled: “Assessing Investment Policies of GCC Countries: Translating economic diversification strategies into sound international investment policies” On 5 April 2011 in Abu Dhabi Organised in co-operation of and hosted by the Ministry of Economy of the United Arab Emirates 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. INTRODUCTION: ECONOMIC AND FDI OVERVIEW AND DIVERSIFICATION POLICIES ................. 7 1. After an eventful decade, the GCC economies are at a crossroads ....................................... 7 2. Diversification remains a key challenge in the GCC ............................................................... 9 3. The GCC needs to address human capital issues ................................................................. 17 II. PRESENTATION OF THE ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY .......................................................... 21 1. The BCDS methodology ........................................................................................................ 21 2. The BCDS investment policy dimension and the stocktaking study .................................... 22 III. ASSESSMENT OF INVESTMENT POLICIES – FDI LAW AND POLICY OF GCC COUNTRIES ........ 24 1. Restrictions to National Treatment ..................................................................................... -

Working with Brunei to Get the Rebalance Right

Working with Brunei to Get the Rebalance Right Daniel L. Shields United States Ambassador to Brunei Darussalam hen President Obama delivered his address to the Australian Parliament in 2011 affirming his strategic decision that the United States will play a Wlarger role in shaping the Asia Pacific region and its future—what came to be called the rebalance—few observers outside Brunei Darussalam might have antici- pated that Brunei would emerge as an essential partner for the United States in the effort to get the rebalance right. But that is what happened. The United States worked closely with Brunei, especially in the context of Brunei’s role as the 2013 Chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), to develop innovative projects to promote comprehen- sive American regional engagement. Two important examples of initiatives to broaden US regional engagement were the Brunei-US English Language Enrichment Project for ASEAN and the US-Asia Pacific Comprehensive Energy Partnership. As these projects were being implemented, Brunei’s effective Chairmanship of ASEAN helped lower the temperature in the region on the South China Sea and promote broad regional military-to- military cooperation, particularly through a Brunei-hosted Humanitarian Assistance/ Disaster Relief and Military Medicine exercise that brought together 18 nations, including the United States and China. The rebalance also includes a commercial side, and US companies have enjoyed increased success in Brunei. Looking ahead, the opportunities for trade should multiply once the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, in which Brunei and the United States are among the twelve parties, come to a successful conclusion. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency.