Boylan's Fugue in 'Sirens'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Arias Concert Program

Graduate Vocal Arts Program Bard College Conservatory of Music OPERA WORKSHOP Stephanie Blythe and Howard Watkins, instructors “Thank you, do you have anything in German?” Friday, March 5 at 8pm Wo bin ich? Engelbert Humperdinck (1854 - 1921) from Hänsel und Gretel Diana Schwam, soprano Ryan McCullough, piano Nimmermehr wird mein Herze sich grämen Friedrich von Flotow (1812 - 1883) from Martha Joanne Evans, mezzo-soprano Elias Dagher, piano Glück, das mir verblieb Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 - 1957) from Die tote Stadt Jardena Gertler-Jaffe, soprano Diana Borshcheva, piano Einst träumte meiner sel’gen Base Carl Maria von Weber (1786 - 1826) from Der Freischütz Kirby Burgess, soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Witch’s Aria Humperdinck from Hänsel und Gretel Maximillian Jansen, tenor Diana Borshcheva, piano Da Anagilda sich geehret… Ich bete sie an Reinhard Kaiser (1674 - 1739) from Die Macht der Tugend Chuanyuan Liu, countertenor Ryan McCullough, piano Arabien, mein Heimatland Weber from Oberon Micah Gleason, mezzo-soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Da schlägt die Abschiedsstunde Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791) from Der Schauspieldirektor Meg Jones, soprano Sung-Soo Cho, piano Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen Korngold from Die tote Stadt Louis Tiemann, baritone Diana Borshcheva, piano Wie du warst Richard Strauss (1864 - 1949) from Der Rosenkavalier Melanie Dubil, mezzo-soprano Elias Dagher, piano Presentation of the Rose Strauss from Der Rosenkavalier Samantha Martin, soprano Elias Dagher, piano Arie des Trommlers Viktor Ullman (1898 - 1944) from Der Kaiser von Atlantis Sarah Rauch, mezzo-soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Weiche, Wotan, weiche! Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883) from Das Rheingold Pauline Tan, mezzo-soprano Sung-Soo Cho, piano Nun eilt herbei! Otto Nicolai (1810 - 1849) from Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor Alexis Seminario, soprano Elias Dagher, piano SYNOPSES: Wo bin ich? Hänsel und Gretel Engelbert Humperdinck, Adelheid Wette, 1893 Gretel has just awakened from a deep sleep in the forest. -

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist Makinsey Grant . Bb Clarinet Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) was written in 1849. It is the first movement of three pieces written to promote the creative notion of the performer. It allows the performer to be unrestricted with their imagination. Fantasy Piece No. 1 is written to be “Zart und mit Ausdruck” which translates to tenderly and expressively. It begins in the key of A minor to give the audience the sense of melancholy then ends in the key of A major to give resolution and leave the audience looking forward to the next movements. (M. Grant) Tony Lozano . Guitar Tu Lo Sai by Giuseppe Torelli (1650 – 1703) Tu lo sai (You Know It) This musical piece is emotionally fueled. Told from the perspective of someone who has confessed their love for someone only to find that they no longer feel the same way. The piece also ends on a sad note, when they find that they don’t feel the same way. “How much I do love you. Ah, cruel heart how well you know.” (T. Lozano) Ruth Sorenson . Mezzo Soprano Sure on this Shining Night by Samuel Barber Samuel Barber (1910 – 1981) was an American composer known for his choral, orchestral, and opera works. He was also well known for his adaptation of poetry into choral and vocal music. Considered to be one of the composers most famous pieces, “Sure on this shining night,” became one of the most frequently programmed songs in both the United States and Europe. -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

Hoirup Presents Study

Hoirup Presents Study Symphony· Guild Holds First Night Meeti~g Donald Hoirup, instructor in voice at Wake Forest Leading roles will be taken by three.singers new to local University, presented the pre-concert study of Bizet's audiences. Dorothy Krebift, mezzo soprano will portray "Carmen" for members of the Winston-Salem Symphony the gypsy, Carmen; James McCray, tenor, will be the cor- Guild Thursday night in the lower auditorium of Centenary poral, Don Jose; and Thomas Palmer, baritone, will sing Uriit«I Methodist Church. the role of the bullfighter, Escamillo. 1he public was invited to this first night meeting of the David Partington is chorus master, and John Iuele, con- G~ild, which was preceded by a social hour. · ductor. Beverly Culbreath, Steve Wellman, Lewis Turner, Stqdents from the N.C. School of the Arts, Debbie Smith, Andrew Beattie, [?eborah Smith and Martha Lindsey will sopr$10, and Martha Sizemore, mezzo soprano, joined be in the supporting cast. Mrs. Sandy Rushing is also train- Hoir11P in his presentation. One of his own voice students, ing a children's chorus which will sing in addition to the Mar~ne Hyatt, mezzo soprano, and Mrs. Margaret Kolb, chorus of Symphony Chorale members. pianiat, also took part in the program of excerpts from the Hoirup, who joined the Wake Forest faculty in 1972, holds popular opera. · degrees from Juilliard School of Music and has studied in Carmen", to be presented March 7 and 8 at Reynolds Frankfurt, Germany. A bass-baritone, he sang last year in ~nald Hoirup, Wake Forest faculty member gives a Audi&orium, will be sung in English this time. -

American Spiritual Program Fall 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009 • 7:30 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church • 1401 Camden Avenue, Salisbury Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music influenced by the spiritual. This concert is sponsored by The Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund;SU President Janet Dudley-Eshbach; Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Diane Allen; Dean Maarten Pereboom, Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts; Dean Dennis Pataniczek, Samuel W. and Marilyn C. Seidel School of Education and Professional Studies; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council. THE AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM THE SPIRITUAL Walk Together, Children ..........................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Jacob’s Ladder ..........................................................................................................arr. Harry Robert Wilson Angelique Clay, Soprano Soloist Plenty Good Room ..................................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Go Down, Moses ............................................................................................................arr. Harry T. Burleigh Frederick Jackson, Bass-Baritone Is There Anybody Here? ....................................................................................................arr. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Italian Theater Prints, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9b69q7n7 No online items Finding aid for the Italian theater prints, ca. 1550-1983 Finding aid prepared by Rose Lachman and Karen Meyer-Roux. Finding aid for the Italian theater P980004 1 prints, ca. 1550-1983 Descriptive Summary Title: Italian theater prints Date (inclusive): circa 1550-1983 Number: P980004 Physical Description: 21.0 box(es)21 boxes, 40 flat file folders ca. 677 items (623 prints, 13 drawings, 23 broadsides, 16 cutouts, 1 pamphlet, 1 score) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The Italian theater prints collection documents the development of stage design, or scenography, the architecture of theaters, and the iconography of commedia dell'arte characters and masks. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Italian Access Open for use by qualified researchers. Publication Rights Contact Library Reproductions and Permissions . Preferred Citation Italian theater prints, ca. 1550-1983, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, Accession no. P980004. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/cifaP980004 Acquisition Information Acquired in 1998. Processing History The Italian theater prints collection was first processed in 1998 by Rose Lachman. Karen Meyer-Roux completed the processing of the collection and wrote the present finding aid in 2004. Separated Materials All of the approximately 4380 secondary sources from the Italian theater collection were separated to the library. In addition, ca. 1500 rare books, some of which are illustrated with prints, have also been separately housed, processed and cataloged. -

Sirens: the Basics 2

Thomas Hardy’s Siren by Sarah A. Wray A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Nancy Jane Tyson, Ph.D. Pat Rogers, Ph.D. Marilyn Myerson, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 4, 2007 Keywords: Jude the Obscure, feminist theory, mythology, barmaids, Victorian women, marriage © Copyright 2007, Sarah A. Wray Acknowledgements I would like to thank all of my professors, including: Frances, Marilyn, Dr. Rogers, Dr. Tyson, Pat Nickinson, Dr. Diomede, Kim G., Elizabeth Bell, and Dr. Baum. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate students, my family, and my friends. Table of Contents Abstract ii Chapter One 1 Introduction 1 Sirens: The Basics 2 Beasts 6 Chapter Two 17 Arabella: A Feminist? 17 Song 21 Truth 25 Chapter Three 30 Drowning 30 Conclusion 39 References 41 Bibliography 45 i Thomas Hardy’s Siren Sarah A. Wray ABSTRACT The Sirens episode in The Odyssey is comparably short, but it is one of the most memorable scenes in the epic. Sirens are trying to stop the male narrative, the male quest of Odysseus with their own female “narrative power” (Doherty 82). They are the quintessential marginalized, calling for a voice, a presence, an audience in the text of patriarchy. The knowledge they promise, though, comes with the price of death. They are covertly sexual in Classical antiquity, but since the rise of Christianity, a new Siren emerged from the depths of the sea; instead of the sexually ambiguous embodiment of knowledge, she became fleshy, bestial, and lustful (Lao 113). -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

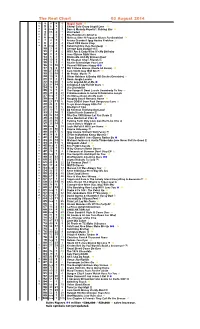

Real Chart Working File 1

The Real Chart 03 August 2014 1 108 8 4 1 Magic! Rude Ý 2 92 6 2 2 Cheryl Cole Crazy Stupid Love Ý 3 91 new 1 3 Bars & Melody Hopeful / Shining Star Ý 4 89 66 2 4 Zhu Faded Ý 5 69 1 8 1 Ella Henderson Ghost ¨ 6 45 new 1 6 Melissa Steel ft Popcaan Kisses For Breakfast Ý 7 44 4 5 2 Ariana Grande ft Iggy Azalea Problem 8 8 43 2 2 2 Charli XCX Boom Clap 9 40 new 1 9 Bakermat One Day (Vandaag) Ý 10 3 9 1 George Ezra Budapest ¨ 11 7 4 2 Will I Am & Cody Wise It’s My Birthday 12 9 4 5 Jess Glynne Right Here 13 5 3 1 Rixton Me And My Broken Heart 14 10 9 1 Ed Sheeran Sing / Friends ¨ 15 14 3 4 Nicole Scherzinger Your Love 16 13 36 1 Pharrell Williams Happy uu 17 24 2 17 MK ft Alana Always (Route 94 Remix) Ý 18 27 13 1 Sam Smith Stay With Me ¨ Ý 19 15 18 1 Mr Probz Waves ¨ 20 19 6 3 Oliver Heldens & Becky Hill Gecko (Overdrive) 8 21 11 2 11 Neon Jungle Louder 22 16 26 1 John Legend All of Me u 23 17 14 5 Coldplay A Sky Full Of Stars 8 24 18 5 5 Sia Chandelier 25 12 7 6 The Vamps ft Demi Lovato Somebody To You 8 26 20 2 20 X Ambassadors & Jamie N Commons Jungle 27 new 1 27 Vic Mensa Down On My Luck Ý 28 new 1 28 Naughty Boy ft Romans Home Ý 29 28 11 6 Fuse ODG ft Sean Paul Dangerous Love 8 30 44 2 30 Troye Sivan Happy Little Pill Ý 31 22 3 6 Ella Eyre If I Go 32 30 7 19 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 33 21 16 3 Clavin Harris Summer ¨ 34 32 14 1 Rita Ora I Will Never Let You Down ¨ 35 26 34 7 Idina Menzel Let It Go u 36 23 16 3 Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This ¨ 37 25 14 7 Jason Derulo Wiggle ¨ 38 new 1 38 Leah McFall ft Will.i.am Home Ý -

Faust Libretto English Translation

Opera Arias Home > Gounod > Faust > Faust Libretto > English Translation Faust Libretto English Translation Cast: FAUST (Tenor) MÉPHISTOPHÉLÈS (Bass) WAGNER (Baritone) VALENTIN (Baritone) SIEBEL (Soprano) MARGUERITE (Soprano) MARTHE (Mezzosoprano) CHORUS young girls, labourers, students, burghers, matrons, invisible demons, church choir, witches,queen and courtesans of antiquity, celestial voices ACT ONE Introduction Faust's study The day is dawning. Faust is sitting at a large table littered with parchments. In front of him lies an open book. FAUST Nothing! In vain do I question, through this zealous vigil, Both Nature and our Maker; No voice comes to murmur in my ear Some word of comfort! I have pined, sad and lonely, Unable to break the fetters Which still bind me to this world! I see nothing! I know nothing! Nothing! Nothing! He closes the book and stands up. The sky lightens! Dark night melts away As the new dawn advances! Another day! Another day grows bright! O Death, when will you come And shelter me beneath your wing? Faust English Libretto.docx Page 1 He takes a phial from the table. Well, since Death shuns me, Why should I not go to him? Hail, O my last morning! Fearless, I reach my journey's end; And I am, with this potion, The sole master of my fate! He pours the contents of the phial inside a crystal beaker. As he is about to drink, girlish voices are heard outside YOUNG GIRLS outside Ah! Lazy girl, who are Still slumbering! The day already shines In its golden cloak. The bird already sings Its careless songs; The caressing dawn Smiles on the harvest; The brook prattles, The flower opens to daylight, All Nature Awakens to love! FAUST Idle echoes of human bliss, Go your way! Go by, go by! O you, my forefathers'cup, so often filled, Why do you thus shake in my hand? Again he raises the beaker to his lips. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home