The Humanities: What Now? What Next? David Laurence This Working

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Psycholinguistic Background of L1 Polish Students of L3 Spanish

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ ARTICLES MARTÍN TESTA 10.15290/CR.2018.22.3.04 University of Warsaw The Psycholinguistic Background of L1 Polish Students of L3 Spanish Abstract. The study was aimed at exploring the psycholinguistic background of Polish students of L3 Spanish. Two groups of students (B1 and B2) were asked to fill out a survey with questions related to proficiency, self-confidence, language identity, usefulness, prestige, stress, sound, and frequency of use. The last part of the survey included some questions about psychotypology, as well. In terms of foreign language anxiety, Spanish was ranked by most of the students as the most stressful language. A follow-up session was carried out with them in order to try to discuss the reasons behind their choices, and their feedback helped to shed some light on the topic and raised further questions about the role and impact of Polish teachers of Spanish in Poland. Keywords: sociolinguistics, stress, foreign language anxiety, L3 Spanish, third language acquisition, multilingual- ism, psychotypology. 1. Introduction The following study was aimed at exploring the psycholinguistic background of Polish students of L3 Spanish from a multilingual point of view. That is why, the study begins with a short sum- mary of the the situation of English both in Europe and, more precisely, in Poland in order to give a general picture of the linguistic situation in which the participants of this study grew up. The next section deals with the impact of positive attitudes on language learning and a short review of Dewaele’s (2010) findings in terms of foreign language anxiety (FLA). -

The Language of the Incontinent Body in Margaret Laurence's the Stone

Technologies of Identity: The Language of the Incontinent Body in Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel DONNA PALMATEER PENNEE N AN ESSAY ENTITLED “Identity, Genealogy, History” Nikolas Rose explains the Foucauldian sense of “technology” that is signalled I in this paper: Technology, here, refers to any assembly structured by a practical rationality governed by a more or less conscious goal. Human tech- nologies are hybrid assemblages of knowledges, instruments, persons, systems of judgement, buildings and spaces, underpinned at the pro- grammatic level by certain presuppositions about, and objectives for, human beings.… Perhaps the insistence upon an analytic of human technologies is one of the most distinctive features of the approach, … an analysis which does not start from the view that the technologizing of human conduct is malign, but rather examines the ways in which human beings have been simultaneously capacitated and governed by their organization within a technological field. (132; emphasis added) Rose’s terms help to clarify something of what is meant by the “produc- tivity” of “power,” and, while “not start[ing] from the view that the technologizing of human conduct is malign” can permit a more complex view of the historical field than is usually available through cause-effect lenses, I want nevertheless to address the malignancy of technologies of the self. This hurtfulness of history is represented in the literal and figu- rative workings of the incontinent body in Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel, a novel that displays the armature of a self simultaneously capaci- tated and governed by the force fields of negative difference. -

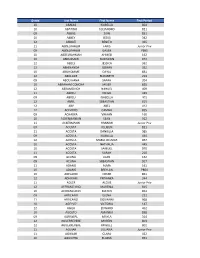

State of New Jersey Medicaid Fraud Division Provider Exclusion Report

State of New Jersey 1 Medicaid Fraud Division Provider Exclusion Report Updated on: 8/23/2021 **ADDITIONAL NPI NUMBERS MAY BE ASSOCIATED WITH THE LISTED INDIVIDUALS/ENTITIES** PROVIDER NAME TITLE DATE OF NPI NUMBER STREET CITY STA ZIP ACTION EFFECTIVE EXPIRATION BIRTH TE DATE DATE 2258 PHARMACY, INC. 2258 THIRD AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10035 SUSPENSION 7/20/2003 6522 VENTNOR AVE. 6522 VENTNOR AVENUE VENTNOR NJ 08406 DISQUALIFICATION PHARMACY, INC. ABARCA, CHERYL R. LPN 8/15/1962 528 3RD STREET NEWARK NJ 07107 SUSPENSION 6/20/2005 ABASHKIN, ROMAN CHHA 12/21/1981 72 RIDGEVIEW TERRACE WAYNE NJ 07470 DISQUALIFICATION 5/29/2015 ABASHKIN, ROMAN CHHA 12/21/1981 72 RIDGEVIEW TERRACE WAYNE NJ 07470 DISQUALIFICATION 6/3/2016 ABBASSI, JADAN MD 9/19/1944 1194807255 1618 MAIN AVENUE CLIFTON NJ 07011 DISQUALIFICATION 11/21/2016 PERMANENT ABBASSI, JADAN MD 9/19/1944 1194807255 115 NELLIS DRIVE WAYNE NJ 07470 DISQUALIFICATION 6/20/2018 PERMANENT ABDALLA, IZZELDIN 4/5/1967 1116 ANNE STREET ELIZABETH NJ 07201 DISQUALIFICATION 11/10/1999 ABDELGANI, AMIR ALLENWOOD USP WHITE DEER PA 17887 DISQUALIFICATION 11/26/2001 ABDELGANI, FADIL TERRE HAUTE USP TERRE HAUTE IN 47808 DISQUALIFICATION 11/26/2001 ABDELHAMID, MANAL RPH 5/28/1969 7100 BOULEVARD EAST, 11G GUTTENBERG NJ 07093 DEBARMENT 3/15/2001 ABDOLLAHI, MITRA DMD 8/31/1966 1033329230 646 N. SARATOGA DRIVE MOORESTOWN NJ 08057 DISQUALIFICATION 11/5/2007 7/19/2019 ABERBACH, STEVEN RPH 8/5/1944 23 STONEGATE DRIVE WATCHUNG NJ 07069 DEBARMENT 12/19/2003 ABOOD, ABDOLMAID S. 1/20/1966 64 BEVAN STREET JERSEY CITY NJ 07306 SUSPENSION 5/7/1997 ABOODS MEDICAL LIVERY 64 BEVAN STREET JERSEY CITY NJ 07306 DISQUALIFICATION 5/22/1994 ABOUELHODA, AHMED RPH 3/23/1974 33-17 60TH STREET, APT. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Founding-Era Translations of the U.S. Constitution Christina Mulligan

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 2016 Founding-Era Translations of the U.S. Constitution Christina Mulligan Michael Douma Hans Lind Brian Quinn Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mulligan, Christina; Douma, Michael; Lind, Hans; and Quinn, Brian, "Founding-Era Translations of the U.S. Constitution" (2016). Constitutional Commentary. 24. http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOUNDING-ERA TRANSLATIONS OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION Christina Mulligan, Michael Douma, Hans Lind, & Brian Quinn* I. INTRODUCTION After the United States Constitution was drafted in 1787, the document was translated into German and Dutch for the German- and Dutch-speaking populations of Pennsylvania and New Y ork. 1 Although copies of both the German- and Dutch- Christina Mulligan is an Assistant Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School. Michael Douma is the Director of the Institute for the Study of Markets and Ethics at Georgetown University. Hans Lind is a Giamatti Fellow at Yale University. Brian Quinn holds an M.A. in Comparative Literature from the University of Chicago and a B.A. in English from Harvard University. Where uncited, Dutch interpretations were completed by Michael Douma and German interpretations were completed by Hans Lind. The authors wish to thank Jack Balkin, William Baude, Randy Barnett, Randy Beck, Jud Campbell, Nathan Chapman, Dan Coenen, Kent Dolphay, Riehard Epstein Bill Cilod, Christopher Green, Jill Hasday, Jeanne Hoffman, Martin Kagel, Kurt Lash, Robert Leider, Michael McConnell, Tim Meyer, Joe Miller, Thomas E. -

Using Cognates in a French-Romanian

Using Cognates in a French - Romanian Lexical Alignment System: A Comparative Study Mirabela Navlea Amalia Todira şcu Linguistique, Langues, Parole (LiLPa) Linguistique, Langues, Parole (LiLPa) Université de Strasbourg Université de Strasbourg 22, rue René Descartes 22, rue René Descartes BP, 80010, 67084 Strasbourg cedex BP, 80010, 67084 Strasbourg cedex [email protected] [email protected] Romanian - German (Vertan and Gavril ă, 2010). Abstract Most of the cognate identification modules used by these systems are purely statistical. As far as we know, no cognate identification method is available for French and Romanian. This paper describes a hybrid French - Roma- Cognate identification is a difficult task due to nian cognate identification module. This mod- the high orthographic similarities between bilin- ule is used by a lexical alignment system. Our gual pairs of words having different meanings. cognate identification method uses lemma- tized, tagged and sentence-aligned parallel Inkpen et al. (2005) develop classifiers for corpora. This method combines statistical French and English cognates based on several techniques, linguistic information (lemmas, dictionaries and manually built lists of cognates. POS tags) and orthographic adjustments. We Inkpen et al. (2005) distinguish between: evaluate our cognate identification module and - cognates ( liste (FR) - list (EN)); we compare it to other methods using pure sta- - false friends ( blesser (‘to injure’) (FR) - bless tistical techniques. Thus, we study the impact (EN)); of the used linguistic information and the or- - partial cognates ( facteur (FR) - factor or mail- thographic adjustments on the results of the man (EN)); cognate identification module and on cognate - genetic cognates ( chef (FR) - head (EN)); alignment. Our method obtains the best results in comparison with the other implemented sta- - unrelated pairs of words ( glace (FR) - ice (EN) tistical methods. -

Teaching Intermediate and Advanced Language Classes: Proficiency, Content, and Culture

12 UCLA Language Alliance Symposium Spring 2016 Teaching Intermediate and Advanced Language Classes: Proficiency, Content, and Culture Monday, May 16, 2016 12:30 - 5:15 PM Powell Library 186 Program 12:30-1:00 PM Lunch Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 1:00-2:15 PM 2:25-3:50 PM 4:00-5:15 PM Patricia Wiley “Content and Juliana Wijaya “Proficiency Asako Hayashi Takakura culture in the intermediate and content-based teaching “Developing web-based German language at the intermediate level of multi-level materials for classroom” Indonesian” Japanese content-based instruction” Michelle Smith “Designing Kim Jansma & Laurence Continued on 4 appropriate writing activities Deni-Higney “Task-based Georgiana Galateanu to engage low-intermediate instruction in French” “Urban folklore in the students of Chinese” Romanian language Dean David Schaberg classroom” Gemma Repiso “Integrating prosody in the intermediate Tara Rensch “Teaching Anna Kudyma “Teaching Catalan classroom” awareness in German” advanced Russian: Problems and solutions” UCLA Language Alliance Symposium Teaching Intermediate and Advanced Language Classes: Proficiency, Content, and Culture Monday, May 16, 2016 12:30 - 5:15 P.M. Powell Library 186 PROGRAM 12:30-1:00 LUNCH 1:00-2:15 SESSION 1 Patricia Wiley: “Content and Culture in the Intermediate German Language Classroom” Michelle Smith: “Designing Appropriate Writing Activities to Engage Low Intermediate Students of Chinese” Gemma Repiso: “Integrating Prosody in the Intermediate Catalan Classroom" 2:15-2:25 BREAK 2:25-3:50 SESSION 2 Juliana -

Indigenous and Afrikaans Borrowings in South African Writers: J.M

Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Memòria del Treball de Fi de Grau Indigenous and Afrikaans Borrowings in South African Writers: J.M. Coetzee and Zakes Mda Sofía Belén Reynés Barrientos Grau d'Estudis Anglesos Any acadèmic 2019-20 DNI de l’alumne:43177797N Treball tutelat per Cristina Suárez Gómez Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica S'autoritza la Universitat a incloure aquest treball en el Repositori Autor Tutor Institucional per a la seva consulta en accés obert i difusió en línia, amb Sí No Sí finalitats exclusivament acadèmiques i d'investigació X Paraules clau del treball: South Africa, South African English, borrowings, indigenous languages, Afrikaans Abstract South Africa offers a great cultural diversity due to the huge amount of groups that gradually settled in the country throughout the centuries – from the Khoe-San people, the first settlers, to European immigrants. Hence, the nation's linguistic diversity is very rich: there are eleven official languages – being Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans the most spoken ones – and many non-official languages spoken in the whole country. Since the establishment of the English language during the settlement of British colonies in the region, South African English has been influenced by many languages which have had an impact on aspects such as vocabulary, pronunciation or grammar. The aim of this paper resides on creating a data of indigenous and Afrikaans borrowings in South African English to classify them into different categories and analyze them. In order to do this, the borrowings have been collected from three novels of two South African writers – Life and Times of Michael K (1983) by J.M. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

Full Text Introduction Into the Study of Romanian Language

Introduction in the Study of Romanian Language A textbook for foreign students Bagiu, Lucian Vasile 2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bagiu, L. V. (2018). Introduction in the Study of Romanian Language: A textbook for foreign students. Editura Aeternitas, Universitatea "1 Decembrie 1918" Alba Iulia. Total number of authors: 1 Creative Commons License: Unspecified General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 The final chapter (Romanian language today) presents the LUCIAN VASILE BÂGIU Romanian language in synchrony. It explores essential issues, such as: the double state of Romanian (Romance and Balkan), the individuality of Romanian within Romance context and Balkan language area, and an etymological analysis of Romanian vocabulary. -

Romanian Canadiana1

Ad Americam. Journal of American Studies 21 (2020): ISSN: 1896-9461, https://doi.org/10.12797/AdAmericam.21.2020.21.01 Licensing information: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Rodica Albu Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi, Romania [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3117-0478 Cristina Petraş Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi, Romania [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0093-8002 Romanian Canadiana1 The rise of Canadian Studies in Romania, particularly in the academia, as well as their recent (relative) decline, is presented with emphasis on the last twenty-five years. Indi- vidual interest and enthusiasm as well as the foundation of CEACS contributed to the Canadian Studies “boom” in 2000-2012, when Canadian Studies Centers were founded in several important Romanian universities, the number of Canadian Studies classes at BA and MA levels increased, large research projects were completed, PhD theses were initi- ated and quite a few defended. Key words: Romanian-Canadian relations; Canadian Studies in Romania; CEACS; re- search projects; teaching; academic events 1. The broad picture The last two decades of the 19th century witnessed the beginnings of the Romanian migration towards Canada, but the Canadian state was brought to the attention of the average Romanian as a well-defined political and cultural entity only starting with the significant year 1967, when a touring Canadian exhibition revealed to us the history and the main attractions of a country celebrating the centennial in its present form. From 1990 onwards, in -

Grade Last Name First Name First Period 10 ABADIA ISABELLA 804

Grade Last Name First Name First Period 10 ABADIA ISABELLA 804 10 ABATINO ALEJANDRO 821 09 ABBAS ZAIN 851 10 ABBEY JESUS 342 12 ABBIATI BENITO 365 11 ABDELRAHEM FARIS Junior Priv 09 ABDELRAHEM GASIM P865 10 ABDELRAHMAN AHMED 162 10 ABDUSSAMI TAISHAWN 972 12 ABELS JESSICA 362 12 ABHINANDA GOWRI 352 10 ABILHOMME DAYAL 831 12 ABOLADE ELIZABETH 213 09 ABOU HANA SARAH 204 10 ABRAHAM CONCHA JAVIER 835 12 ABRAMOVICH NAHUEL 409 11 ABREU DIEGO 429 09 ABREU ISABELLA 401 12 ABRIL SEBASTIAN 815 12 ABY ABEL 412 12 ACEVEDO CAMILA 855 09 ACHARYA VIHAAN 160 10 ACKERMANIAN SEAN 912 11 ACKERMANN HANNAH Junior Priv 09 ACOSTA ALLISON 821 11 ACOSTA DANIELLA 985 09 ACOSTA ISABELLA 434 12 ACOSTA MARIA DELMAR 857 10 ACOSTA NATHALIA 445 10 ACOSTA SAMUEL 970 11 ACOSTA SARAH 210 09 ACUNA JUAN 162 09 ACUNA SEBASTIAN 917 11 ADAMS ALMA 161 10 ADAMS BREYLAN P864 10 ADELARDI OMAR 851 12 ADHIKARI PRIYANKA 344 11 ADLER ALEXIS Junior Priv 12 AFFRANCHINO MARTINA 815 10 AFFRANCHINO MATEO 853 09 AFRICANO ELENA 222 11 AFRICANO GIOVANNI 968 10 AGELVIZ VICTORIA 147 12 AGILA EDWARD 452 10 AGOSTO AMANDA 858 09 AGRAWAL MAYLA 314 12 AGUERREVERE MARTIN 803 12 AGUERREVERE MIGUEL 802 11 AGUIAR JULIANA Junior Priv 11 AGUILAR CLARA 422 10 AGUILERA ELAINA 951 Grade Last Name First Name First Period 11 AGUINAGA VELA GABRIELA 957 09 AGUIRRE CHRISTIAN 413 10 AGUIRRE DANIEL 419 12 AGUIRRE DIEGO 437 12 AGUIRRE JASON 223 11 AGUIRRE SARAVIA FRANCO 210 12 AHN JOSHUA 421 11 AIAZZI XIOMARA 445 12 AIKEN NICHOLAS 178 10 AIKMAN CORDELL 948 11 AILDASANI JULIA 340 11 AILDASANI RAPHAELA 854 09 AIRES RADA