The Signaling Value of Hunted Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol 1 by Marv Wolfman

Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol 1 by Marv Wolfman Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. Ebook Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol 1 available for review only, if you need complete ebook "Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol 1" please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >>> *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every ebook is in the library. You can choose FREE Trial service and download "Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol 1" ebook for free. Book Details: Review: I was born in the late 70s, so I have high nostalgia for the 80s and 90s comics. I was definitely more of a DC guy (but Marvel had some good stuff too). The New Titans is my all time favorite series. I know Adrian Chase debuted much earlier in Titans history than that, but that is how I am familiar with him. I only read a handful of issues of this series,... Original title: Vigilante by Marv Wolfman Vol. 1 Series: Vigilante Paperback: 320 pages Publisher: DC Comics (April 18, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1401268722 ISBN-13: 978-1401268725 Product Dimensions:6.6 x 0.6 x 10.2 inches File Format: pdf File Size: 17561 kB Book File Tags: Description: Spinning off from the classic NEW TEEN TITANS!As a district attorney for New York City, Adrian Chase used the legal system to keep the streets safe. But when it came to protecting his own family, that system failed him. After losing his wife and children in a failed assassination attempt, Chase makes the fateful decision to take justice into his own.. -

Green Arrow Escape from Super Max

Green arrow escape from super max Continue In: Green Arrow Movies, Green Arrow: Escape from Super Max, Cancelled Comments Movies Share Green Arrow: Escape from Super Max was a movie in its early stages of development, but due to no real updates from 2008 it can be assumed that it is no longer in development. In the film Green Arrow had to be framed for murder, sent to prison and had to flee. Actors of the story produced by David Goyer and Justin Marx wrote the screenplay for the film starring Green Arrow originally called Super Max. On June 5, 2008, the film was renamed Green Arrow: Escape from Super Max. Reportedly, the storyline is that the hero (framed for a crime he didn't commit) must avoid a maximum-security prison filled with B and C a list of villains and rogue superheroes. MTV published an interview with Marx on its website. In it, he says this: It's a very, very huge prison. I majored in architecture in college, and designing how I actually started in. for Super Max, designing this prison, it had to be the kind of thing that was character in itself, Marks said. We're in a world where instead of just trying to contain a guy who's really big, you're trying to contain a guy who can - in the case of icicles - who can freeze things. What kind of cell does a guy need to neutralize his powers? So to escape from Super Max they have to go through the most difficult heist we've ever seen involving superpowers. -

No.102$8.95 Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc

Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.102 February 2018 $8.95 1 82658 00116 2 INTERVIEW WITH DEADPOOL’S FIRST WRITER,FABIANNICIEZA FIRST INTERVIEW WITHDEADPOOL’S Punisher! Featuring Beatty, Claremont, Collins,Lash, Michelinie, anda Liefeldcover! Deathstroke •VigilanteTaskmaster •WildDogCable •andArchieMeets the ISSUE!MERCS &ANTI-HEROES ™ Volume 1, Number 102 February 2018 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Rob Liefeld COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Terry Beatty Bob McLeod Jarrod Buttery David Michelinie Marc Buxton Fabian Nicieza Joe Casey Luigi Novi Ian Churchill Scott Nybakken Shaun Clancy Chuck Patton Max Allan Collins Philip Schweier FLASHBACK: Deathstroke the Terminator 2 Brian Cronin David Scroggy A bullet-riddled bio of the New Teen Titans breakout star Grand Comics Ken Siu-Chong Database Tod Smith BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: Taskmaster 17 Tom DeFalco Anthony Snyder Is he really the best at everything he does? Christos Gage Allen Stewart Mike Grell Steven Thompson FLASHBACK: The Vigilante 23 Gene Ha Fred Van Lente Who were those masked men in this New Teen Titans spinoff? Heritage Comics Marv Wolfman Auctions Doug Zawisza FLASHBACK: Wild Dog 36 Sean Howe Mike Zeck Max Allan Collins and Terry Beatty unmask DC’s ’80s vigilante Brian Ko Paul Kupperberg ROUGH STUFF 42 James Heath Lantz Grim-and-gritty graphite from Grell, Wrightson, Zeck, and Liefeld -

THE SUPERHERO BOOK SH BM 9/29/04 4:16 PM Page 668

SH BM 9/29/04 4:16 PM Page 667 Index Miss Masque, Miss Acts of Vengeance, 390 Adventure Comics #253, A Victory, Nightveil, Owl, Acy Duecey, 4478 586 A Carnival of Comics, 229 Pyroman, Rio Rita, AD Vision, 21, 135, 156 Adventure Comics #432, “A Day in the Life,” 530 Rocketman, Scarlet Adam, 97 446 (ill.) A Distant Soil, 21 Scorpion, Shade, She- Adam, Allen, 117 Adventure Comics #482, A Touch of Silver (1997), 275 Cat, Yankee Girl Adam Strange, 3–4, 317, 441, 180 (ill.) AAA Pop Comics, 323 Academy X, 650 500, 573, 587 Adventurers’ Club, 181 Aardvark-Vanaheim, 105 Acclaim Entertainment, 563, Justice League of Ameri- Adventures in Babysitting, 525 Abba and Dabba, 385 613 ca, member of, 294 Adventures into the Unknown, Abbey, Lynn, 526 Ace, 42 Adamantium, 643 434 Abbott, Bruce, 147 Ace Comics, 160, 378 Adams, Art, 16, 44–45, 107, The Adventures of Aquaman ABC See America’s Best Ace Magazines, 427 254, 503 (1968–1969), 296 Comics (ABC) Ace of Space, 440 Adams, Arthur See Adams, Art Adventures of Batman (TV ABC News, 565 Ace Periodicals, 77 Adams, Jane, 62, 509 series), 491 ABC Warriors, 441 Ace the Bat-Hound, 59, 72, Adams, Lee, 545 The Adventures of Batman and Abhay (Indian superhero), 283 402, 562 Adams, Neal, 22, 25, 26, 32, Robin (1969–1970), 56, 64 Abin Sur, 240, 582 “Aces,” 527 47, 59, 60, 94, 104, 174, The Adventures of Batman and Abner Cadaver, 416 ACG, 42 177, 237, 240, 241, 334, Robin (1994–1997), 56, 67, Abomination, 259–260, 266, Achille le Heel, 342 325, 353, 366, 374, 435, 493 577 Acolytes, 658 445, 485, 502, 503, 519, The Adventures of Bob Hope, Aboriginie Stevie, 583 Acrata (Planet DC), 282 542, 582, 635, 642 103, 502 About Comics, 194 Acrobat, 578 Adapt (Australian superhero), Adventures of Captain Africa, Abra Kadabra, 220, 575 Action #23, 550 283 378 Abrams, J. -

Scandal-Lists S

SCANDAL-LISTS S KARL SHAW “Comedy equals tragedy plus timing” - Anon. CONTENTS S 1. CHOICE CUTS 2. LOVE HURTS 3. COURTING THE MUSE 4. HEALTH & BEAUTY 5. CRIME & PUNISHMENT 6. THE JOY OF SECTS 7. MAD, BAD & DANGEROUS TO KNOW 8. MISCELLANY 9. END NOTES 10. FURTHER READING CHAPTER ONE CHOICE CUTS 1 GOAT’S TESTICLES TO GO: 10 NATIONAL DELICACIES S 1. Cena Molida (contains roasted mashed cockroaches) - Belize 2. Fried, roasted or boiled guinea pig - Ecuador 3. Rat meat sausages - Philippines 4. Crispy Fried Rat with Lemon / Boiled Bamboo Rat / Dessicated petrified deer’s penis /dog’s penis - China 5. Boodog (goat broiled inside a bag made from the carefully cut and tied goatskin: the goat is either barbecued over an open fire or cooked with a blow torch) - Mongolia. 6. Monkey toes - Indonesia 7. Larks tongues - England (16th century)/ Pickled Puffin - North Wales (19th cen tury) 8. Salted horsemeat sandwiches - Netherlands 9. Durian fruit - South-East Asia (has a fragrance identical to that of a rotting corpse) 10. Khachapuri, the traditional cheese pie of the former Soviet republic of Georgia. In 1995 authorities closed down a bakery whose specialty was khachapuri when it emerged that the pies were being baked in the Tbilisi morgue. 2 10 FAMOUS FOODIES S 1. Emperor Elagabalus; famed for 12-hour long banquets, eating as Romans often did, reclining and demanding sex between courses. He also liked to surprise his guests by the rarity of the dishes he provided, a typical menu featuring flamingo brains, camel brains, parrot heads and sows udders. -

Arrow: with the Prometheus Twist, Who Could Be Vigilante?

Arrow: With The Prometheus Twist, Who Could Be Vigilante? Author : If you have not watched this past weeks episode of the CW's hit show Arrow, titled "Fighting Fire with Fire", then I suggest you save this article for later. We will be delving into some serious SPOILERS in regards to the show, and in particular this season's big bad, Prometheus. So this is your last chance to turn around and come back once you have watched the episode. Still with us? Ok good. So obviously, the big reveal on the show surprisingly was dropped on right in the middle of the episode. Following a brief fight between Prometheus and Vigilante, in which Vigilante ended up going off the edge of a roof (and virtually disappeared), fans were hit with a bit of a twist. Prometheus unmasked, to reveal the face of District Attorney Adrian Chase, who is played by Josh Segarra. Talk about a mid-episode surprise. [Kenny] Now, most fans had long expected Chase to have a dark side. Up to this point, he has been one of Oliver's go to officials while in the Mayor's Office, having helped out Mayor Queen on multiple occasions. But there has always been something fishy about Star City's DA. When news broke that Oliver was being called out for covering up the death of Detective Billy Malone, suspicion of Chase grew even more given the cover-up was his idea. However, it was expected to be a lock that he would be the man under the mask of the baddie Vigilante. -

Arrow: Why Is Oliver Not Suspicious of Chase’

Arrow: Why Is Oliver Not Suspicious Of Chase's Easy Surrender? Author : This has arguably been one of the better seasons of the CW's hit show, Arrow. While many were disappointed in a lackluster season four, season five has gone back to the darker, grittier tone that fans love. As a fan of all the Arrowverse shows, I have found myself looking forward to Wednesday nights more than Tuesdays when The Flash airs. A big reason why has to do with this season's big bad. His name is Prometheus. Or as some like to call him, the throwing star killer. Oh wait, we even know his "real" name. But the name he goes by the most nowadays is Adrian Chase. Chase is one of the best psychological baddies I have ever witnessed on television. Everything he does is for a reason. And that reason usually has something to do with getting inside of Oliver Queen's head. He is also almost always a step ahead of Team Arrow, helping with his mind games. As a result, Oliver has been on the brink of giving up on a handful of occasions. So last week, something just felt a bit off. At the end of the episode, Oliver began to play some mind games of his own. He told Chase that his father wanted to disown him. As a result, Chase essentially got to his knees and gave up. He was taken into custody and ended up in an A.R.G.U.S. cell. As a result of their win, Team Arrow was seen celebrating. -

00 Regional Indices.Indb

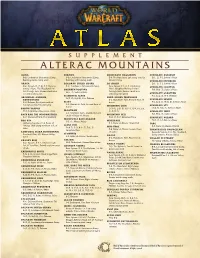

SUPPLEMENT ALTERAC MOUNTAINS ALINA DERMOT LIEUTENANT HAGGERDIN SYNDICATE ASSASSIN B-8, Lordamere Internment Camp, B-8, Lordamere Internment Camp, E-8, The Headland, Left camp outside E:(1, 2), F-2, Sofera’s Naze Building inside camp walls Building within camp walls Alterac Valley SYNDICATE ENFORCER ARAGA DOLORAN SHIELD GUARD LO’GROSH E:(1, 2), F-2, Sofera’s Naze Rare Spawn, D:(7, 8), E-9, Dalaran, B-8 , Lordamere Internment Camp Rare Spawn, F-3, G-5, Crushridge SYNDICATE FOOTPAD Sofera’s Naze, The Headland, Lvl DRUNKEN FOOTPAD Hold, Slaughter Hollow, Lvl 39 F-8, H:(6, 7), Sofera’s Naze 35 Average Rare; Roams small area H:(6, 7), Sofera’s Naze Average Rare; Roams small area around spawn point around spawn point SYNDICATE SABOTEUR ELEMENTAL SLAVE F-2, G:(2, 3), H-3, Dalaran ARCHMAGE ANSIREM A:(7, 8), B:(5-8), C-6, Dalaran LORD ALIDEN PERENOLDE RUNEWEAVER E-2, Dandred’s Fold, Second fl oor of SYNDICATE SENTRY B-8, Dalaran, Road just north of ELYSA house F-2, G:(2, 3), H:(3, 4), Sofera’s Naze Lordamere Internment Camp E-2, Dandred’s Fold, Second fl oor of SYNDICATE SPY house MOUNTAIN LION BARON VARDUS D:(7-9), E:(8, 9), F:(7-9), G-8, I-5, J:(5, H:(4, 5), I:(4, 5), Sofera’s Naze H-4, Strahnbrad, Basement of inn FROSTMAW 6), K:(5, 6) SYNDICATE THIEF E-7, Growless Cave, (Summon) Cave F-8, H:(6, 7), Sofera’s Naze BATH’RAH THE WINDWATCHER south of Ruins of Alterac MOUNTAIN YETI K-7, Chillwind Point, Troll platform D:(6, 7), E-7, Growless Cave SYNDICATE WIZARD FROSTWOLF BATTLEGUARD H:(4, 7), I-4, Sofera’s Naze BRO’KIN I:(5, 6), Alterac Valley MUCKRAKE -

The Vigilantes Free Ebook

FREETHE VIGILANTES EBOOK W E B Griffin,William E Butterworth | 450 pages | 29 Jul 2015 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780515149593 | English | New York, United States Vigilantism But his son's influence has smoothed the stories considerably and reduced the guffaw factor by several times. Vigilantes is a good example. Detective Matt Payne, one of the mainstay characters of the Badge of Honor series, finds himself trying to solve the mystery of a series of "pop- and-drop" murders in Philadelphia. To Mr Raymond K. Roberts, a real estate investor and six-year Army veteran who monitored the vigilantes, the parade of jacked-up pick-up trucks filled with armed men resembled Afghanistan. Vigilante is the name used by several fictional characters appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. Notable individuals to assume the alias include Greg Saunders and Adrian Chase. An original incarnation appeared in The CW series Arrow, played by Clayton Chitty and Johann Urb and voiced by Mick Wingert. Adrian Chase also appeared as a separate character, played by Josh Segarra. Vigilante (comics) Vijirante?) are people who voluntarily carry out duties usually done by Pro Heroes without paying attention to the law. Due to the Hero regulations and Quirk restriction laws, people are not allowed to perform heroic duties out on their own and vigilantism is therefore illegal. Vigilante is the name used by several fictional characters appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. Notable individuals to assume the alias include Greg Saunders and Adrian Chase. An original incarnation appeared in The CW series Arrow, played by Clayton Chitty and Johann Urb and voiced by Mick Wingert. -

Vs. System Official Card Reference October 4, 2006

Vs. System Official Card Reference October 4, 2006 ¡Olé!, Construct (DGL-205C) Plot Twist, 1 Target character you control gets +3 ATK this attack if it has the same cost as another character you control. 3 . 2 . 1 . (DCR-145R) Plot Twist, 2 Play 3 . 2 . 1 . only during the combat phase and only if you control a Villains United character. <p> If 3 . 2 . 1 . is in your resource row, KO 3 . 2 . 1 . and KO target location. Otherwise, replace that location. A Child Named Valeria (MOR-066R) Plot Twist, 3 Choose one or both: If you control Mr. Fantastic and Invisible Woman, characters with cost 3 or less you control cannot be stunned this turn; or if you control Dr. Doom, stun target exhausted character with cost 2 or less. A Day Unlike Any Other, Team-Up (MAV-190C) Plot Twist, 2 If there are exactly two different team affiliations among characters you control, choose those affiliations. <p> Ongoing: Characters you control, as well as cards in your hand, deck, and KO'd pile, with either of the chosen affiliations have both of them. <p> Pay 3 endurance >>> Turn A Day Unlike Any Other face down. A Death in the Family (DOR-142R) Plot Twist, 1 As an additional cost to play A Death in the Family, pay 5 endurance. <p> KO target stunned character. Lose endurance equal to its cost. A Moment of Crisis (DCR-031C) Plot Twist, 2 Choose an identity. Characters you control gain the chosen identity this turn. <p> If you control a JSA character and A Moment of Crisis is in your resource row, draw a card. -

I Must Become Something Else”: Identity Construction and the Role of the Superhero in the TV Series Arrow

“I must become something else”: Identity construction and the role of the superhero in the TV series Arrow „I must become something else”: Identitätskonstruktion und die Superheldenrolle in der Fernsehserie Arrow by Mareike Sophie Wagner A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo and the Universitaet Mannheim in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Intercultural German Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada / Mannheim, Germany, 2020 © Mareike Sophie Wagner 2020 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich die Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebe- nen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder sinngemäß aus Veröffentli- chungen in schriftlicher oder elektronischer Form entnommen sind, habe ich als solche unter Angabe der Quelle kenntlich gemacht. Mir ist bekannt, dass im Falle einer falschen Versiche- rung die Arbeit mit „nicht ausreichend“ bewertet wird. Ich bin ferner damit einverstanden, dass meine Arbeit zum Zwecke eines Plagiatsabgleichs in elektronischer Form versendet und ge- speichert werden kann. ii Abstract This thesis deals with how the protagonist of the CW superhero TV series Arrow constructs his identity. Arrow tells the story of Oliver Queen, who returns home after being shipwrecked and assumed dead, to start working as the vigilante superhero Arrow. As a character leading a life split in two – a private and a superhero life – Oliver Queen has difficulties answering the ques- tion of who he really is, especially after his time as a castaway and his connection to various, more or less criminal organizations for which he had to take on different identities.