INQUIRY Into EDUCATION in REMOTE and COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

Store Nutrition Report and Market Basket Survey.Pdf

Store Nutrition Report and Market Basket Survey April 2014 Nganampa Health Council Erin McLean, Kate Annat and Prof Amanda Lee April 2014 Executive Summary The report provides Market Basket pricing and data analysis of Mai Wiru compliance with standardised food and nutrition checklists from stores on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in South Australia collected in April 2014. The report focuses on the Mai Wiru group stores (Pipalyatjara, Kanpi, Amata, Fregon and Pukatja). Pricing data was also collected from Mimili (Outback Stores), Indulkana (independent) and Coles and IGA Foodlands supermarkets in Alice Springs. The purpose of this report is to provide key recommendations for Mai Wiru store councils to aid decision-making regarding food and nutrition issues. Data was collected in-store from 7-11 April 2014. Information was collected on the price, availability and promotion of foods, as well as Mai Wiru store achievement of the Remote Indigenous Stores and Takeaways (RIST) checklist benchmarks and implementation of nutrition recommendations from the previous Market Basket report (September, 2013). Nutrition promotion activities were also performed in all the Mai Wiru stores, including one pot cooking demonstrations and installation of sugar-in-food displays and posters. Results show that, in April 2014, Mai Wiru stores: • Are clean, functional and well stocked; • Provide a wide range of healthy foods and beverages; and • Price healthy foods at a competitive rate for remote areas. In April 2014 the average price of the Market Basket in the Mai Wiru stores was $734 dollars and had increased only 0.3% since September 2014. In comparison to the other stores monitored during the same period the Mai Wiru store prices were 4.3% less than Mimili, 1.0% more than Indulkana, only 13.0% more than Alice Springs IGA Foodlands and 34.4% more than Coles. -

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

A Long Way to Go in Nuclear Debate, Says Aboriginal Congress of SA

Aboriginal Way Issue 60, Spring 2015 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Aboriginal Congress of South Australia A long way to go in nuclear debate, says Aboriginal Congress of SA In early August, the Aboriginal During July and August, the Royal Parry Agius, Alinytjara Wiluara Natural waste dump” and the Royal Commission Congress of South Australia Commission engaged regional and Resources Board Member reinforced the is nothing more than mere formality. convened in Port Augusta to remote communities including Coober notion of an appropriate timeline in his Karina Lester, Aboriginal Congress discuss the issues and concerns Pedy, Oak Valley, Ceduna, Port Lincoln, submission. Mr Agius wrote, “we note of SA member said it is clear by the of potential expansion of uranium Port Augusta, Whyalla, Port Pirie, levels of concern within our communities submissions to the Royal Commission mining in SA, including the Ernabella, Fregon, Mimili, Indulkana, that suggest that the timeframe for that Aboriginal People do not support development of a nuclear Ceduna, Amata, Kanpi and Pipalyatjara. consultation on the risks and opportunities the Nuclear Fuel Cycle. waste dump. through the Royal Commission is Aboriginal Congress of SA Chair, insufficient”. Through the initial “Our views are clear in the submissions The State Government launched a Tauto Sansbury said the engagement conversations with community members and we need to ensure that this gets public inquiry on the Nuclear Fuel Cycle with Aboriginal Communities is there is, he added, “a level of confusion across to the Commissioner. We need by calling a Royal Commission in March. welcomed however the consultation about what was being discussed”. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Infrastructure Requirements to Develop Agricultural Industry in Central Australia

Submission Number: 213 Attachment C INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS TO DEVELOP AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN CENTRAL AUSTRALIA 132°0'0"E 133°0'0"E 134°0'0"E 135°0'0"E 136°0'0"E 137°0'0"E Aboriginal Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Allocation fully economic Requirements Area (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Karlantijpa 1000 20 Tennant ALT Creek + Warumungu $12m $3.94m Frewena ALT 2000 40 (Frewena) 19°0'0"S Frewena 19°0'0"S LIKKAPARTA Tennant Creek Karlantijpa ALT Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements 20°0'0"S (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) 20°0'0"S Illyarne ALT 1500 30 Warrabri ALT 4000 100 $2.9m Western MUNGKARTA Murray $26m (Already Davenport Downs & invested via 1000 ABA $3.5m) Singleton WUTUNUGURRA Station CANTEEN CREEK Illyarne ALT Murray Downs and Singleton Stations ALI CURUNG 21°0'0"S 21°0'0"S WILLOWRA TARA Warrabri ALT AMPILATWATJA WILORA Ahakeye ALT (Community farm) ARAWERR IRRULTJA 22°0'0"S NTURIYA 22°0'0"S PMARA JUTUNTA YUENDUMU YUELAMU Ahakeye ALT (Adelaide Bore) A Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & B Water LARAMBA Control Aboriginal Land Water jobs when direct Infrastructure C District Trust (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements Ahakeye ALT (6 Mile farm) (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Ahakeye ALT Pine Hill Block B ENGAWALA community farm 30 5 ORRTIPA-THURRA Adelaide bore 1000 20 Ti-Tree $14.4m $3.82m Ahakeye ALT (Bush foods precinct) Pine Hill ‘B’ 1800 20 BushfoodsATITJERE precinct 70 5 6 mile farm 400 10 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S PAPUNYA Potentia Potential Approximate Bore Field & HAASTS BLUFF Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust l Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocati fully economic Requirements on (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) A.S. -

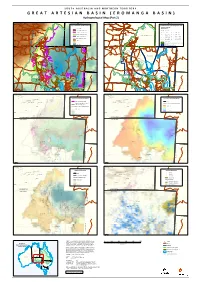

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

Calendar of Events Unsafe Areas for Spectators

CALENDAR UNSAFE AREAS BUILD A EXTINGUISH OF EVENTS FOR SPECTATORS SAFE FIRE A CAMP FIRE Make sure there is a 4 x 4 metre clearing Remove slow burning logs and completely extuingish with water WHAT, WHERE & WHEN OF FINKE RACING VEHICLES CAN OVERSHOOT. Dig a hole about 90 cm in diameter and 30 cm State of Origin Screening - 6:00pm deep Shovel the boundary soil over the fire to completely cover it Wednesday 9th June - Lasseters Casino Use the soil that you have removed to make a Finke Street Party & Night Markets - 5:00pm FOR YOUR SAFETY WE INSIST YOU DON’T boundary for the fire Never leave a burning fire unattended Thursday 10th June - Todd Mall STAND/CAMP IN THE MARKED AREAS Build your fire in the hole Ensure all campfires are extinguished before Scrutineering - 4:00pm leaving the campsite Friday 11th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Have some water nearby Prologue - 7:30am Saturday 12th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Race Day 1 - 7:00am Under Section 74 of the Bushres Management Act Sunday 13th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct TIGHT CORNERS KEEP LEFT OR RIGHT 2016 (NT) if is an oence if a person leaves a re Race Day 2 - 7:30am unattended. Monday 14th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone Presentation Night - 6:30pm 4 Meters 90 cm 4 Meters Maximum penalty 500 penalty units or 5 years Monday 14th June - A/S Convention Centre imprisonment (1 penalty unit = $155) TIGHT CORNERS TURN AT CROSS ROAD MERCHANDISE No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone ADMISSION FINKE -

PITJANTJATJARA Council Inc. FINDING

PITJANTJATJARA MS 1497 PITJANTJATJARA Council Inc. FINDING AID Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 1497 PITJANTJATJARA COUNCIL ARCHIVES A3a/B1 Minutes of meetings of the Pitjanjatjara Council 1976-1981 Originals and copies (see also MS 1168) In English and Pitjantjatjara Contents: I. Pitjantjatjara Council Inc. Minutes of meetings (originals) 1) Amata, SA, 13 July 1976, 11 p., map 2) Docker River, NT, 7 September 1976, 6p. 3) Ipdulkana, 1 December 1976, 8p. 4) Blackstone (Papalankutja), WA, 22-23 February 1977, 12p. 5) Ernabella (Pukatja), SA, 19-20 April 1977, 5p. 6) Warburton, WA, 21 -22 June 1977, 10p. 7) Amata, SA, 3 August 1977, 4p. (copy) 8) Ernabella, SA, 26-27 September 1977, 4p. 9) Puta Puta, SA, 28-29 November 1977, 7p. 10) Fregon, SA, 21-22 February 1978, 9p. 11) Mantamaru (Jamieson), WA, 2-3 May 1978, 6p. 12) Pipalyatjara, SA, 17-18 July 1978, 6p. 13) Mimili, SA, 3-4 October 1978, 10p. 14) Uluru (Ayers Rock), NT, 4-5 December 1978, 6p. 15) Irrunytju (Wingelinna), 7-8 February 1979, 6p. 16) Amata, SA, 3-4 April 1979, 6p. • No minutes issued for June and August 1979 meetings 17) Nyapari, SA, 15-16 November 1979, 9p. 18)lndulkana, 10-11 December 1979, 6p. 19) Adelaide, SA, 13-14 February 1980, 6p. 20) Adelaide, SA, 13-14 February 1980 - unofficial report by WH Edwards, 2p. 21) Blackstone (Papulankutja), WA, 17-18 April 1980,3p. 22) Jamieson (Mantamaru), WA, 22 July 1980, 4p. 23) Katjikatjitjara, 10-11 November 1980, 4p. (copy) 24) Docker River, 9-11 February 1981, 5p. -

Native Title Groups from Across the State Meet

Aboriginal Way www.nativetitlesa.org Issue 69, Summer 2018 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Above: Dean Ah Chee at a co-managed cultural burn at Witjira NP. Read full article on page 6. Native title groups from across the state meet There are a range of support services Nadja Mack, Advisor at the Land Branch “This is particularly important because PBC representatives attending heard and funding options available to of the Department and Prime Minister the native title landscape is changing… from a range of organisations that native title holder groups to help and Cabinet (PM&C) told representatives we now have more land subject to offer support and advocacy for their them on their journey to become from PBCs present that a 2016 determination than claims, so about organisations, including SA Native independent and sustainable consultation had led her department to 350 determinations and 240 claims, Title Services (SANTS), the Indigenous organisations that can contribute currently in Australia. focus on giving PBCs better access to Land Corporation (ILC), Department significantly to their communities. information, training and expertise; on “We have 180 PBCs Australia wide, in of Environment Water and Natural That was the message to a forum of increasing transparency and minimising South Australia 15 and soon 16, there’s Resources (DEWNR), AIATSIS, Indigenous South Australian Prescribed Bodies disputes within PBCs; on providing an estimate that by 2025 there will be Business Australia (IBA), Office of the Corporate (PBCs) held in Adelaide focussed support by native title service about 270 – 290 PBCs Australia wide” Registrar of Indigenous Corporations recently. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL