Credit Card ABS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conditional Approval #312 May 1999

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Washington, DC 20219 Conditional Approval #312 May 1999 DECISION OF THE OFFICE OF THE COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY ON THE APPLICATION TO CHARTER NEXTBANK, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA MAY 8, 1999 I. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSAL On December 10, 1998, NextCard, Inc., San Francisco, California (“NCI”), filed an application with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) to charter a new national credit card bank as specified in the Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987, as amended (CEBA). The proposed bank will be headquartered in San Francisco, California, and will be titled NextBank, National Association (“Bank”).1 The Bank has applied to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) for deposit insurance and will apply to become a member of the Federal Reserve System. The Bank has also filed an operating subsidiary application with the OCC to own and operate NextCard Funding Corp. (“NFC”), a Delaware corporation that is currently wholly-owned by NCI. The applications have been supplemented from time to time with additional or amended information. No comments were received from the public regarding these applications. NCI, formerly called Internet Access Financial Corporation, launched the NextCard VISA card in December 1997. The product, which NCI calls the First True Internet VISA, is marketed to consumers exclusively through its Web site, www.nextcard.com. The NextCard can be used for both online and offline purchases and offers several product and service enhancements specifically designed for the Internet-enabled consumer. These include a customized application process, Internet-based account management, and online shopping enhancements. -

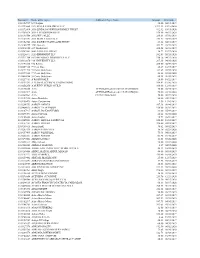

List of Merchants 4

Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered 9001575*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9013807*HBC SRL 05/02/2018 9017439*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9001605*AGENZIA LAMPO SRL 05/02/2018 9013943*CASA EDITRICE LIB 05/02/2018 9017440*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003338*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014076*MAILUP SPA 05/02/2018 9017441*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003369*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014276*CCS ITALIA ONLUS 05/02/2018 9017442*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9003946*GIUNTI EDITORE SP 05/02/2018 9014368*EDITORIALE IL FAT 05/02/2018 9017574*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004061*FREDDY SPA 05/02/2018 9014569*SAVE THE CHILDREN 05/02/2018 9017575*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004904*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014616*OXFAM ITALIA 05/02/2018 9017576*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004949*ELEMEDIA SPA 05/02/2018 9014762*AMNESTY INTERNATI 05/02/2018 9017577*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9004972*ARUBA SPA 05/02/2018 9014949*LIS FINANZIARIA S 05/02/2018 9017578*PULCRANET SRL 05/02/2018 9005242*INTERSOS ASSOCIAZ 05/02/2018 9015096*FRATELLI CARLI SO 05/02/2018 9017676*PIERONI ROBERTO 05/02/2018 9005281*MESSAGENET SPA 05/02/2018 9015228*MEDIA SHOPPING SP 05/02/2018 9017907*ESITE SOCIETA A R 05/02/2018 9005607*EASY NOLO SPA 05/02/2018 9015229*SILVIO BARELLO 05/02/2018 9017955*LAV LEGA ANTIVIVI 05/02/2018 9006680*PERIODICI SAN PAO 05/02/2018 9015245*ASSURANT SERVICES 05/02/2018 9018029*MEDIA ON SRL 05/02/2018 9007043*INTERNET BOOKSHOP 05/02/2018 9015286*S.O.F.I.A. -

A GUIDE to ELECTION YEAR ACTIVITIES of SECTION 501(C)(3) ORGANIZATIONS

A GUIDE TO ELECTION YEAR ACTIVITIES OF SECTION 501(c)(3) ORGANIZATIONS BY STEVEN H. SHOLK, ESQ. STEVEN H. SHOLK, ESQ. GIBBONS P.C. ONE GATEWAY CENTER NEWARK, NEW JERSEY 07102-5310 (973) 596-4639 [email protected] ONE PENNSYLVANIA PLAZA 37th FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10119-3701 (212) 613-2000 Copyright Steven H. Sholk 2016 All Rights Reserved 776148.37 999999-00262 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATUTORY PROVISIONS ON CONTRIBUTIONS, EXPENDITURES, AND ELECTIONEERING ......................................................................................................... 1 STATUTORY AND REGULATORY PROVISIONS ON CONTRIBUTIONS TO AND FUNDRAISING FOR SECTION 501(c)(3) ORGANIZATIONS ................................ 159 REGULATORY PROVISIONS ON CONTRIBUTIONS, EXPENDITURES, AND ELECTIONEERING ..................................................................................................... 191 VOTER REGISTRATION AND GET-OUT-THE-VOTE DRIVES........................................ 315 VOTER GUIDES....................................................................................................................... 326 CANDIDATE APPEARANCES AND ADVERTISEMENTS ................................................ 339 CANDIDATE DEBATES ......................................................................................................... 352 CANDIDATE USE OF FACILITIES AND OTHER ASSETS ................................................ 355 WEBSITE ACTIVITIES .......................................................................................................... -

Attendee Bios

ATTENDEE BIOS Ejim Peter Achi, Shareholder, Greenberg Traurig Ejim Achi represents private equity sponsors in connection with buyouts, mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, joint ventures, restructurings and other investments spanning a wide range of industries and sectors, with particular emphasis on technology, healthcare, industrials, consumer packaged goods, hospitality and infrastructure. Rukaiyah Adams, Chief Investment Officer, Meyer Memorial Trust Rukaiyah Adams is the chief investment officer at Meyer Memorial Trust, one of the largest charitable foundations in the Pacific Northwest. She is responsible for leading all investment activities to ensure the long-term financial strength of the organization. Throughout her tenure as chief investment officer, Adams has delivered top quartile performance; and beginning in 2017, her team hit its stride delivering an 18.6% annual return, which placed her in the top 5% of foundation and endowment CIOs. Under the leadership of Adams, Meyer increased assets managed by diverse managers by more than threefold, to 40% of all assets under management, and women managers by tenfold, to 25% of AUM, proving that hiring diverse managers is not a concessionary practice. Before joining Meyer, Adams ran the $6.5 billion capital markets fund at The Standard, a publicly traded company. At The Standard, she oversaw six trading desks that included several bond strategies, preferred equities, derivatives and other risk mitigation strategies. Adams is the chair of the prestigious Oregon Investment Council, the board that manages approximately $100 billion of public pension and other assets for the state of Oregon. During her tenure as chair, the Oregon state pension fund has been the top-performing public pension fund in the U.S. -

US V. Visa USA Inc., Visa International Corp., and Mastercard International

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, : : Plaintiff,: : 98 Civ. 7076 (BSJ) : v. : Decision : VISA U.S.A. INC., : VISA INTERNATIONAL CORP., and : MASTERCARD INTERNATIONAL : U.S. District Court INCORPORATED, : Filed 10-9-2001 : S.D.of N.Y. Defendants. : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x BARBARA S. JONES, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE INTRODUCTION This civil action was brought by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., against the defendants, VISA U.S.A. INC., (“Visa U.S.A.”), VISA INTERNATIONAL CORP., (“Visa International”) (collectively “Visa”) and MASTERCARD INTERNATIONAL INCORPORATED, (“MasterCard”). It involves the U.S. credit and charge card industry, which has only four significant network services competitors: American Express, a publicly owned corporation; Discover, a corporation owned by Morgan Stanley Dean Witter; and the defendants Visa and MasterCard, which are joint ventures, each owned by associations of thousands of banks. The Government claims, in two counts, that each of the defendants is in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, which provides that “every contract, combination in the 1 form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States ... is declared to be illegal.” 15 U.S.C. § 1. Count One centers around the governance rules of Visa and MasterCard, which permit members of each association to sit on the Board of Directors of either Visa or MasterCard, although they may not sit on both. Count Two targets the associations’ exclusionary rules, under which members of each association are able to issue credit or charge cards of the other association, but may not offer American Express or Discover cards. -

List of Participating Merchants Mastercard Automatic Billing Updater

List of Participating Merchants MasterCard Automatic Billing Updater 3801 Agoura Fitness 1835-180 MAIN STREET SUIT 247 Sports 5378 FAMILY FITNESS FREE 1870 AF Gilroy 2570 AF MAPLEWOOD SIMARD LIMITED 1881 AF Morgan Hill 2576 FITNESS PREMIER Mant (BISL) AUTO & GEN REC 190-Sovereign Society 2596 Fitness Premier Beec 794 FAMILY FITNESS N M 1931 AF Little Canada 2597 FITNESS PREMIER BOUR 5623 AF Purcellville 1935 POWERHOUSE FITNESS 2621 AF INDIANAPOLIS 1 BLOC LLC 195-Boom & Bust 2635 FAST FITNESS BOOTCAM 1&1 INTERNET INC 197-Strategic Investment 2697 Family Fitness Holla 1&1 Internet limited 1981 AF Stillwater 2700 Phoenix Performance 100K Portfolio 2 Buck TV 2706 AF POOLER GEORGIA 1106 NSFit Chico 2 Buck TV Internet 2707 AF WHITEMARSH ISLAND 121 LIMITED 2 Min Miracle 2709 AF 50 BERWICK BLVD 123 MONEY LIMITED 2009 Family Fitness Spart 2711 FAST FIT BOOTCAMP ED 123HJEMMESIDE APS 2010 Family Fitness Plain 2834 FITNESS PREMIER LOWE 125-Bonner & Partners Fam 2-10 HBW WARRANTY OF CALI 2864 ECLIPSE FITNESS 1288 SlimSpa Diet 2-10 HOLDCO, INC. 2865 Family Fitness Stand 141 The Open Gym 2-10 HOME BUYERS WARRRANT 2CHECKOUT.COM 142B kit merchant 21ST CENTURY INS&FINANCE 300-Oxford Club 147 AF Mendota 2348 AF Alexandria 3012 AF NICHOLASVILLE 1486 Push 2 Crossfit 2369 Olympus 365 3026 Family Fitness Alpin 1496 CKO KICKBOXING 2382 Sequence Fitness PCB 303-Wall Street Daily 1535 KFIT BOOTCAMP 2389730 ONTARIO INC 3045 AF GALLATIN 1539 Family Fitness Norto 2390 Family Fitness Apple 304-Money Map Press 1540 Family Fitness Plain 24 Assistance CAN/US 3171 AF -

Form 10-K/A Washington Mutual, Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K/A Amendment No. 1 ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2005 Commission File Number 1-14667 WASHINGTON MUTUAL, INC. (Exact nameof registrant as specified in its charter) Washington 91-1653725 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 1201 Third Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98101 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (206) 461-2000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Litigation Tracking Warrants™ NASDAQ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer as defined inRule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes # No " . Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes " No # . Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for thepast 90 days. -

Credit Cards, Consumer Complaints the CFPB’S Consumer Complaint Database Gets Real Results for Credit Card Holders

Credit Cards, Consumer Complaints The CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database Gets Real Results for Credit Card Holders Credit Cards, Consumer Complaints The CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database Gets Real Results for Credit Card Holders PIRGIM Education Fund Miles Unterreiner and Tony Dutzik, Frontier Group Ed Mierzwinski and Laura Murray, U.S. PIRG Education Fund January 2014 Acknowledgments PIRGIM Education Fund and Frontier Group sincerely thank Sarah Wolff of the Center for Responsible Lending and Ruth Susswein of Consumer Action for their review of drafts of this document, as well as for their insights and suggestions. The authors sincerely thank Ben- jamin Davis for his editorial assistance, Spencer Alt for his research assistance and Ashleigh Giliberto of U.S. PIRG Education Fund for her assistance with Appendix B of this report. PIRGIM Education Fund and Frontier Group thank The Ford Foundation for making this report possible. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of PIRGIM Education Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. 2014 PIRGIM Education Fund. Some Rights Reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported License. To view the terms of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0. With public debate around important issues often dominated by special interests pursuing their own narrow agendas, PIRGIM Education Fund offers an independent voice that works on behalf of the public interest. PIRGIM Education Fund works to protect consumers and promote good government. -

Public Disclosure

O Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Limited Purpose Public Disclosure February 20, 2001 Community Reinvestment Act Performance Evaluation Providian National Bank Charter Number 1333 295 Main Street Tilton, New Hampshire 03276 Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Western District Office 50 Fremont Street, Suite 3900 San Francisco, CA 94105 NOTE: This evaluation is not, nor should it be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion, or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. General Information The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) requires each federal financial supervisory agency to use its authority when examining financial institutions subject to its supervision, to assess the institution’s record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low- and moderate- income neighborhoods, consistent with safe and sound operation of the institution. Upon conclusion of such examination, the agency must prepare a written evaluation of the institution’s record of meeting the credit needs of its community. This document is an evaluation of the CRA performance of Providian National Bank, prepared by The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the institution’s supervisory agency, as of February 20, 2001. The agency evaluates performance in assessment area(s), as they are delineated by the institution, rather than individual branches. This assessment area evaluation may include the visits to some, but not necessarily all of the institution’s branches. The agency rates the CRA performance of an institution consistent with the provisions set forth in Appendix A to 12 CFR Part 25. -

Insurance, Term Life Insur- Some Years Ago, Mary Meeker (Morgan Stanley Dean Wit- Ance, and Credit Card Interchange Fees

Introduction It doesn’t take much research to recognize that the Internet $435 billion-plus in revenues by 2003 from an estimated has already had a profound effect on the delivery of finan- $103 billion today. This projection includes consumer cial services and is likely to bring more radical changes. banking, brokerage services, auto insurance, term life insur- Some years ago, Mary Meeker (Morgan Stanley Dean Wit- ance, and credit card interchange fees. The implied com- ter’s Internet analyst) forecast that financial services would pounded annual growth of 34% will likely prove to be very be among the industries most profoundly affected by the conservative. Internet, since the distribution of financial products doesn’t • Competitive intensity should escalate as technological require any physical exchange of goods. We now believe and regulatory barriers fall. Some financial services pro- that the one-two punch of technology and deregulation will viders will benefit significantly from the potential for reach irreversibly alter the way business is generated in financial and product diversification from the double whammy of the services, particularly on the consumer side. Internet and deregulation. Financial services companies and With massive change under way, the Morgan Stanley Dean technology portals alike are looking for ways to capture Witter U.S. financial services team set out to plot a course consumers nationwide and ultimately worldwide. They will through the new landscape that’s emerging. We tapped our offer a range of services that includes banking, brokerage, Equity Research department and external contacts to for- life, auto and home insurance, retirement and estate plan- mulate a clearer picture of (1) what the Internet means for ning, mortgages, and credit cards. -

The Retirement Plan Summary Plan Description Jpmorgan Chase

The Retirement Plan Summary Plan Description JPMorgan Chase January 1, 2019 This summary plan description applies only to employees who were hired before December 2, 2017 and have a cash balance account in the JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan as of December 31, 2018 (and certain rehires after December 31, 2018). The Retirement Plan The JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan (the “Plan” or Update: Your Summary Plan “Retirement Plan”) is fully paid for by JPMorgan Chase and Description for the JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan provides a foundation for your retirement income. (Replaces the January 1, 2016 summary As discussed in greater detail below, the Plan is now plan description) “frozen” and closed to new entrants. Prior to the freeze, This document is your summary plan description of the JPMorgan Chase participation in the Retirement Plan was automatic once Retirement Plan. This summary plan description provides you with important you completed one year of total service. Your Retirement information required by the Employee Plan benefit is expressed as a cash balance benefit that Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) about the Retirement Plan. grows in a notional bookkeeping account over time through While ERISA does not require pay credits and interest credits. For each month you work at JPMorgan Chase to provide you with benefits, it does mandate that JPMorgan Chase while eligible for the Plan through JPMorgan Chase clearly communicate to December 31, 2019, the company will credit your account you how the Retirement Plan operates and what rights you have under the law regarding with a percentage of your Eligible Compensation — from Plan benefits. -

Unclaimed Warrant Listing

Warrant # Name of the payee Additional Payee Name Amount Pmnt date 1103152937 0.99 Liquor 20.00 04/11/2019 1103393068 1535 RIVER PARK DRIVE LLC 1,277.39 12/15/2020 1103372410 2016 LINDA JO MORGAN FAMILY TRUST 192.82 10/13/2020 1103365638 2018 1 IH BORROWER LP 158.80 09/17/2020 1103196704 20188WY 14 LLC 280.31 07/16/2019 1103165191 2071 MAPLE GLEN LLC 251.57 05/07/2019 1103152748 2644 DAWES STATE LAND TRUST 81.84 04/11/2019 1103146755 3783 Beacon 203.77 03/28/2019 1103214105 429 Nordstram's 380.54 08/22/2019 1103383581 5008 10TH AVE TRUST 36.77 11/17/2020 1103324811 5230 EHRHARDT LLC 542.69 05/28/2020 1103311364 8930 MENDOZA PROPERTIES LLC 116.26 04/23/2020 1103313670 910 UNIVERSITY LLC 297.10 04/30/2020 1103151636 974 Ralphs 400.00 04/09/2019 1103259125 99 Cent Store 25.27 12/17/2019 1103291728 99 Cents Only Store 62.69 03/10/2020 1103299882 99 Cents Only Store 44.46 03/26/2020 1103400284 99 Cents Only Store 40.15 01/05/2021 1103237181 A ROSENDALE 20.00 10/22/2019 1103251592 A TEEM ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 104.02 11/26/2019 1103256250 A.M.WINN PUBLIC GUILD 100.00 12/10/2019 1103175035 AAA ATTN Rolf Hoehenrieder CLM 011BQ628 70.00 05/28/2019 1103301519 AAA ATTN Rolf Hoehenrieder CLM 011BQ628 70.00 03/30/2020 1103367061 AAA CLM 011BQ628401 70.00 09/22/2020 1103152940 Aaron Brambila 20.00 04/11/2019 1103256476 Aaron Constantino 1.50 12/10/2019 1103206753 AARON GARCIA 107.38 08/06/2019 1103404626 AARON HAAKENSON 150.00 01/19/2021 1103167917 AARON JACKSON FORD 31.00 05/09/2019 1103275396 Aaron Jefferson 46.62 01/30/2020 1103166568 Aaron Kaplan