Teaching Professional Responsibility Through Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION Board of Directors Meeting

LEGAL SERVICES CORPORATION Board of Directors Meeting July 20 - 22, 2014 Location: Des Moines Marriott Downtown 700 Grand Avenue Des Moines, Iowa 50309 America’s Partner for Equal Justice Table of Contents I. Schedule ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. Operations & Regulations Committee ♦ Agenda...................................................................................................................................... 6 ♦ Draft Minutes of the Committee’s Open Session Meeting of April 7, 2014 ................. 8 ♦ Private Attorney Involvement Proposed Rule CFR Part 1614 ...................................... 13 ♦ 2015 Grant Assurances ........................................................................................................ 20 ♦ Proposed Rulemaking Agenda .......................................................................................... 95 ♦ Service Eligibility Options for Persons Covered by the Convention Against Torture ............................................................................................. 110 III. Institutional Advancement Committee ♦ Agenda.................................................................................................................................. 113 ♦ Draft Minutes of the Committee's Open Session Meeting of April 6, 2014 ............. 115 ♦ In-kind Contributions Protocol ........................................................................................ 119 IV. Governance -

Ian Siegal Wire the Crazy World of Arthur Brown

OCTOBER 2013 SEPTEMBER 2013 LIVE IN LEICESTER PRESENTS... MAGIC TEAPOT PRESENTS... FRI 4 TUE 3 THE CRAZY WORLD OF ARTHUR BROWN JOHN MURRY £16adv - plus support £10adv - plus Liam Dullaghan The source of Arthur Brown’s music lies beyond both the spiritual Hailing from Tupelo, Mississippi; John Murry’s solo debut album and the material. His first album The Crazy World of Arthur Brown ‘The Graceless Age’ is imbued with the ghosts of the Southern was his theatrical statement of this. It, and the single Fire! - which states and the personal demons that have haunted him throughout came from it - were both a hit on the two sides of the Atlantic. his life. He has described himself as more absorbed in the world He is a performance artist who also became a rock icon and his of literature than in the day-to-day concerns of the modern world, influence was felt through his theatrical musical style, his theatrical and for good reason: he’s second cousin to William Faulkner and presentation, his dancing, and his vocal ability. His voice has been has spent much time with his second cousin’s work. Throughout described as “one of the most beautiful voices in rock music” and his songs in the key of heartbreak, there is nonetheless a strong his presentation is second to none! Recently he won Classic Rock’s and abiding sense of salvation and reconciliation. Showman of the Year Award. www.arthur-brown.com www.johnmurry.com TUE 15 XANDER PROMOTIONS PRESENTS... ROACHFORD THU 12 £12adv £14door KATHRYN WILLIAMS Ever since bulldozing his way onto the scene with unforgettable £12adv £14door - plus Alex Cornish tracks like ‘Cuddly Toy’ and ‘Family Man’ in the late 80s, Andrew Kathryn Williams’ artful and soulful compositions and sweet Roachford’s maverick take on music has spread far and wide. -

(Bass & Vocals), Bruce Gilbert

WIRE 1977–1980 Wire were formed by Colin Newman (guitar & vocals), Graham Lewis (bass & vocals), Bruce Gilbert (guitar) and Robert Grey (drums). The band subjected themselves to a lengthy period of intense, 12-hour rehearsals, honing their (admittedly basic) musical skills until razor-sharp. What emerged was a version of rock shorn of all ornamentation and showbusiness. Newman and Gilbert’s chord sequences often took unexpected turns, Graham Lewis’s unique lyrics were vivid but oblique, and Grey’s drumming was minimal and metronomic. They may have arrived at the same time as punk and drawn on its initial burst of energy, but Wire’s forward-looking attitude meant they always stood apart from it. In fact, Wire could easily lay claim to having been the very first post- punk band. And yet, it’s equally true to say they could be viewed as part of the British tradition of left-field art-school bands that includes Roxy Music and The Pink Floyd. Wire played their debut proper at London’s Roxy club on 1 April, 1977. The band were immediately picked up by prodigious EMI offshoot label Harvest, and their debut album Pink Flag was released in December of the same year. The album was a collection of 21 songs, many of them sharp, abrasive and extremely short – six didn’t even make the one-minute mark. Yet many tracks, such as ‘12XU’ and ‘Ex-Lion Tamer’, are now rightly regarded as classics. Pink Flag received near universal acclaim and would be cited as a major influence on a panoramic range of artists, including Big Black, My Bloody Valentine, Blur, Henry Rollins, Joy Division and R.E.M. -

The Works Brass Band – a Historical Directory of the Industrial and Corporate Patronage and Sponsorship of Brass Bands

The works brass band – a historical directory of the industrial and corporate patronage and sponsorship of brass bands Gavin Holman, January 2020 Preston Corporation Tramways Band, c. 1910 From the earliest days of brass bands in the British Isles, they have been supported at various times and to differing extents by businesses and their owners. In some cases this support has been purely philanthropic, but there was usually a quid pro quo involved where the sponsor received benefits – e.g. advertising, income from band engagements, entertainment for business events, a “worthwhile” pastime for their employees, corporate public relations and brand awareness - who would have heard of John Foster’s Mills outside of the Bradford area if it wasn’t for the Black Dyke Band? One major sponsor and supporter of brass bands, particularly in the second half of the 19th century, was the British Army, through the Volunteer movement, with upwards of 500 bands being associated with the Volunteers at some time – a more accurate estimate of these numbers awaits some further analysis. However, I exclude these bands from this paper, to concentrate on the commercial bodies that supported brass bands. I am also excluding social, civic, religious, educational and political organisations’ sponsorship or support. In some cases it is difficult to determine whether a band, composed of workers from a particular company or industry was supported by the business or not. The “workmen’s band” was often a separate entity, supported by a local trade union or other organisation. For the purposes of this review I will be including them unless there is specific reference to a trade union or other social organisation. -

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

CHARLOTTE PERKINS GILMAN THE YELLOW WALLPAPER and OTHER STORIES © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2011 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2011 Tantor Media, Inc. -

Percipience ≈ a Collection of Poems from the Institutional Library Services Poetry Month April 2014

Percipience ≈ A collection of poems from the Institutional Library Services Poetry Month April 2014 1 [Page Left Intentionally Blank] 2 artwork by CdK 3 [Page Left Intentionally Blank] 4 Table of Contents Introduction. 11 “Ishan” (sincere advice) by Ismail Hassan. 13 Apologies by William M. Porter. 14 White Devil by Nick Harper . 15 Offender Inspiration by Christopher Goerner. 16 Of Wendy I Wonder by Christopher Goerner. 17 To Mom by Christopher Goerner . 18 Not all that Bad for A Dad by Christopher Goerner. 19 Wicked Illusions by Johnathon Soto . 20 Some of My Skeletons by Kebin Hodgson. 21 The Way of Things by Kevin Hodgson . 21 Goodbye by Kevin Hodgson . 21 Love by Talyn Benitez . 22 Life by Talyn Benitez . 22 Nature by Talyn Beniez . 23 Smoke’n the Bubble by Stephen Franks . 24 Grace for Me by David E Cochran . 25 Untitled 2 by Mr. Malcolm J Jackson . 26 The Way of Things by Stephen R. Garland . 29 Forty Acres by Demetrius Dean . 30 I Was There by Stephen R. Garland . 32 The Cost by K. E. Bradford . 33 Truth is Violent by Brandon Pedro-Guerra. 34 What I Am by K. E. Bradford. 36 Where is the Teacher by Vincent Abbott. 37 Never Give Up by Vincent Abbott. 37 5 Prisons and Projects by Vincent Abbott. 38 Here to Simply Be...by Jordan Silverac. 40 Thank You by Ryan Ellenberger. 43 Untitled by Mr. Malcolm J. Jackson. 43 Loving by Darrell Cook. 44 Expressions of a Cloud by Darrell Cook. 46 A Man I Know by Lucas A. -

The Related Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME 0 .2D 093 821 SP 008 AUTHOR , Fleming, Gladys: Andrews, _Ed. TITLE Children's Dance. INSTITUTION American Association for, 'Health., Physicel Education, . -end.Recreation, Washington, D.C. .$0B DATE 73 NOTE 112p. .AVAILABLE FROMAAHPER, 1201 16thStr1eet, N.V., Washington, 20036 (No'price-quoted), . EDRS PRICE M1 7,40.75 BC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS 'Annotated Biblioqraphies;. Audiovisual Aids; A *Children; *Dance; Folk Culture *Guidelines; Teachihg Skills ABSTRACT This book on children's'dence s divided into five parts. Part 1 discusse4the votk of the task rde. Part 2 presents a Statement of belief and some implications and examples Of guidelines.. Other topics discussed are discovering:(0..nceu.a concept of time, _imOressionse.an approach todanCe with boys, and science as a point of devarture for danCe. Part 3 includes diScussions on dance in school, danpe for boys, folk.and-ethnic'contribuiions, and dance and -the related arts. Pat 4 discusses leadership for the 1980s, concerns for tWprolesEion,_and Competencies of the teacher of children's , dance:,; Part i5 lists reouzbesi.inCimAing an annotated bibliography of reading and audiovisual' materials,,pilot projects,activities, and. 'personal, contacts for. children's dance. An. appendix includes a Survey questionnaire, inquiry forms, criteria for viewing selected films, and areas of [teed research.AFD) \ 4.? O 0 , a L' va.-4 e\A CO reN 0 Cr% ..fo .0oipo , it CD tv..:re.:". gm IP so . ,, to.. w s.:..b.a. oi 7. .41 :. 46:0%00 11, o. s. IN,0- .f . :41, 2. Ale _a. 2 fir: ID 4, If .to . -

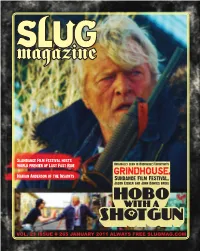

Vol. 21 Issue # 265 January 2011 Always Free Slugmag.Com

VOL. 21 ISSUE # 265 JANUARY 2011 ALWAYS FREE SLUGMAG.COM SaltLakeUnderGround 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround SaltLakeUnderGround 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 21• Issue # 265 • January 2011 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Shauna Brennan Editor: Angela H. Brown [email protected] Managing Editor: Marketing Coordinator: Bethany Jeanette D. Moses Fischer Editorial Assistant: Ricky Vigil Marketing: Ischa Buchanan, Jea- Action Sports Editor: nette D. Moses, Jessica Davis, Billy Adam Dorobiala Ditzig, Hailee Jacobson, Stephanie Copy Editing Team: Jeanette D. Buschardt, Giselle Vickery, Veg Vollum, Moses, Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Josh Dussere, Chrissy Hawkins, Emily Vigil, Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Katie Burkhart, Rachel Roller, Jeremy Riley. Panzer, Rio Connelly, Joe Maddock, SLUG GAMES Coordinators: Mike Alexander Ortega, Mary Enge, Kolbie Brown, Jeanette D. Moses, Mike Stonehocker, Cody Kirkland, Hannah Reff, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Adam Christian. Dorobiala, Jeremy Riley, Katie Panzer, Issue Design: Joshua Joye Jake Vivori, Brett Allen, Dave Brewer, Daily Calendar Coordinator: Billy Ditzig. Jessica Davis Distribution Manager: Eric Granato [email protected] Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Social Networking Coordinator: Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Jesse Katie Rubio Hawlish, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Heath, Design Interns: Adam Dorobiala, Adam Okeefe, Manuel Aguilar, Ryan Eric Sapp, Bob Plumb. Worwood, Chris Proctor, David Ad Designers: Todd Powelson, Frohlich. Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Office Interns: Jessica Davis, Jeremy Jaleh -

Wires Pink Flag Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WIRES PINK FLAG PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wilson Neate | 144 pages | 05 Jun 2009 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826429148 | English | London, United Kingdom Wires Pink Flag PDF Book Most Read Most Shared. More by Martin Aston. Rainy Day Relaxation Road Trip. KEF unveils new compact subwoofer, the KC Wire are, without any doubt, the most consistent rock act in history yes, in history; only the Beatles shorter, brighter, shinier and more diverse arc possibly challenges them. Articles Features Interviews Lists. GP logo Created with Sketch. The sometimes dissonant, minimalist arrangements allow for space and interplay between the instruments; Colin Newman isn't always the most comprehensible singer, but he displays an acerbic wit and balances the occasional lyrical abstraction with plenty of bile in his delivery. Three Girl Rhumba. Feeling Called Love Colin Newman. Topics Wire. I now understand this skill — displayed when they were near-children, and now they are men in their sixties, and creating rapture in me when I was a child, and now I am in my late fifties — drew me to them then, made them a definitive group on my journey as a listener, as a music fan, as a journalist. August 6, Their latest, and 17th, studio album, Mind Hive Pinkflag finds Newman, guitarist Matt Simms, and co-founders bassist Graham Lewis and drummer Robert Grey spinning out incisive tunes that combine tense and ominous moods with sparkling guitars, grinding grooves and unease-provoking imagery. I tried to subvert the concept by writing in different ways, such as reductionism — using fewer chords and brevity — and by using minor chords, which I think is something that really distinguished Wire from our peers. -

Oxford's Music Magazine

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 268 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2017 “Music that comes from the darker parts of our lives has more depth, and resonates more” Little Red Into the deep, dark woods with Oxford’s southern gothic folksters Also in this issue: THE CELLAR - safe, for now... Introducing 31HOURS Ritual Union reviewed plus: all your Oxford music news, reviews and EIGHT PAGES OF LOCAL GIGS NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk this date are still available, priced £12 at www.wegottickets.com/ michaelbarryfund. Youthmovies recently put their entire back catalogue, including CORNBURY FESTIVAL returns next year. This summer’s Cornbury, 2008 album `Good Nature’, up on th Bandcamp on a pay-what-you-like the 14 annual festival, was advertised as the last one after years of basis. Get your fix at financial struggle. But the event, headlined by Bryan Adams, Kaiser ymss.bandcamp.com. Chiefs and Jools Holland’s Rhythm’n’Blues Orchestra, sold out – only the second time the festival has recorded a profit, and after pressure from MAIIANS make a return to live OXFORD CITY FESTIVAL fans and musicians, organiser Hugh Phillimore changed his mind and next action in December. The local th th returns for its fifth outing this year’s Cornbury Festival will take place over the weekend of the 13 -15 instrumental electro band, who July at Great Tew Country Park. -

ANNUAL REPORT of the Librarian of Congress for the fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2004

ANNUAL REPORT of the Librarian of Congress for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2004 annual report of the librarian of congress 2004 ANNUAL REPORT of the Librarian of Congress for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2004 library of congress · washington · 2005 Library of Congress Photographs by Giulia Adelfio (page 104); Architect of 101 Independence Avenue, SE the Capitol (page 160); Reid Baker (page vi); Rob Crandall Washington, DC 20540 (page 35);Anne Day (pages xvi,5,16,28,38,98,149,150,159; inside back cover); Bill Ferris (page 44); Roger Foley (page For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web, ix); Charles Gibbons (pages 19,21,24,27); John Harrington visit http://www.loc.gov. (pages 77,80, 100, 120); Jim Higgins (page ii); Carol High- smith (front cover, inside front cover; pages x, 6; back The annual report is published through the Publishing cover); Kristen Jenkinson-McDermott (page 40); Kevin O≈ce, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washing- Long (page 37); Dee McGee (page 33); Michaela McNichol ton, DC 20540–4980, and the Public A∑airs O≈ce, (pages 66, 78, 84, 111, 153); Robert H. Nickel (page 12); O≈ce of the Librarian, Library of Congress,Washington, Charlynn Pyne (pages 97, 108); Tim Roberts (page 83); DC 20540–1610.Telephone (202) 707–5093 (Publishing) Christine Robinson (page 125); Jim Saah (pages 8, 11, 14); or (202) 707–2905 (Public A∑airs). Fern Underdue (page 103); and Carolyn Wells (page 36). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Front cover: The emblematic Torch of Learning atop the lantern of the Thomas Je∑erson Building’s dome. -

Anatomy of a Trial

Online CLE Anatomy of a Trial 1.5 Oregon Practice and Procedure credits From the Oregon State Bar CLE seminar Fundamentals of Oregon Civil Trial Procedure, presented on September 26 and 27, 2019 © 2019 Dennis Rawlinson. All rights reserved. ii Chapter 9 Anatomy of a Trial1 DENNIS RAWLINSON Miller Nash Graham & Dunn LLP Portland, Oregon Contents I. Strategy—What Is My Goal? . 9–1 A. Opening Statement . 9–1 B. Be Aware of the Jury’s Presence . 9–1 C. Be Organized, Neat, and Prepared . 9–2 D. Present Witnesses Logically. .9–2 E. Be Polite and Professional. .9–2 F. Do Not Overtry Your Case . .9–2 G. Closing Argument . 9–3 II. The Trial Notebook . 9–3 A. Organization . 9–3 B. Depositions in a Notebook. .9–3 C. The Exhibit List and Exhibits. .9–4 D. Witness Testimony . .9–4 III. Use of Depositions in Trial . 9–4 IV. Demonstrative Evidence . 9–5 A. The Visual Connection. .9–5 B. Tell Them—Show Them . 9–5 C. Trial Toys. .9–5 V. Testimonial Evidence . 9–5 A. K.I.S.S. the Jury . 9–5 B. Never Argue with a Witness . 9–6 C. Always Allow a Witness to Escape Gracefully . .9–6 D. Cross-Examination. .9–6 VI. Trial Memorandums. .9–6 VII. Resources. .9–7 VIII. Motions Before or at the Commencement of the Trial . 9–7 A. View of Premises by Jury (ORS 10.100) . 9–7 B. Motion to Exclude Witnesses (OEC 615) . 9–8 C. Motion to Limit Evidence (Motion in Limine) .