A CTCF-Independent Role for Cohesin in Tissue-Specific Transcription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution, Expression and Meiotic Behavior of Genes Involved in Chromosome Segregation of Monotremes

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Evolution, Expression and Meiotic Behavior of Genes Involved in Chromosome Segregation of Monotremes Filip Pajpach , Linda Shearwin-Whyatt and Frank Grützner * School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; fi[email protected] (F.P.); [email protected] (L.S.-W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Chromosome segregation at mitosis and meiosis is a highly dynamic and tightly regulated process that involves a large number of components. Due to the fundamental nature of chromosome segregation, many genes involved in this process are evolutionarily highly conserved, but duplica- tions and functional diversification has occurred in various lineages. In order to better understand the evolution of genes involved in chromosome segregation in mammals, we analyzed some of the key components in the basal mammalian lineage of egg-laying mammals. The chromosome passenger complex is a multiprotein complex central to chromosome segregation during both mitosis and meio- sis. It consists of survivin, borealin, inner centromere protein, and Aurora kinase B or C. We confirm the absence of Aurora kinase C in marsupials and show its absence in both platypus and echidna, which supports the current model of the evolution of Aurora kinases. High expression of AURKBC, an ancestor of AURKB and AURKC present in monotremes, suggests that this gene is performing all necessary meiotic functions in monotremes. Other genes of the chromosome passenger complex complex are present and conserved in monotremes, suggesting that their function has been preserved Citation: Pajpach, F.; in mammals. -

Redundant and Specific Roles of Cohesin STAG Subunits in Chromatin Looping and Transcriptional Control

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 10, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Redundant and specific roles of cohesin STAG subunits in chromatin looping and transcriptional control Valentina Casa,1,6 Macarena Moronta Gines,1,6 Eduardo Gade Gusmao,2,3,6 Johan A. Slotman,4 Anne Zirkel,2 Natasa Josipovic,2,3 Edwin Oole,5 Wilfred F.J. van IJcken,1,5 Adriaan B. Houtsmuller,4 Argyris Papantonis,2,3 and Kerstin S. Wendt1 1Department of Cell Biology, Erasmus MC, 3015 GD Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 2Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne, University of Cologne, 50931 Cologne, Germany; 3Institute of Pathology, University Medical Center, Georg-August University of Göttingen, 37075 Göttingen, Germany; 4Optical Imaging Centre, Erasmus MC, 3015 GD Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 5Center for Biomics, Erasmus MC, 3015 GD Rotterdam, The Netherlands Cohesin is a ring-shaped multiprotein complex that is crucial for 3D genome organization and transcriptional regulation during differentiation and development. It also confers sister chromatid cohesion and facilitates DNA damage repair. Besides its core subunits SMC3, SMC1A, and RAD21, cohesin in somatic cells contains one of two orthologous STAG sub- units, STAG1 or STAG2. How these variable subunits affect the function of the cohesin complex is still unclear. STAG1- and STAG2-cohesin were initially proposed to organize cohesion at telomeres and centromeres, respectively. Here, we uncover redundant and specific roles of STAG1 and STAG2 in gene regulation and chromatin looping using HCT116 cells with an auxin-inducible degron (AID) tag fused to either STAG1 or STAG2. Following rapid depletion of either subunit, we perform high-resolution Hi-C, gene expression, and sequential ChIP studies to show that STAG1 and STAG2 do not co-occupy in- dividual binding sites and have distinct ways by which they affect looping and gene expression. -

Loss of Cohesin Complex Components STAG2 Or STAG3 Confers Resistance to BRAF Inhibition in Melanoma

Loss of cohesin complex components STAG2 or STAG3 confers resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shen, C., S. H. Kim, S. Trousil, D. T. Frederick, A. Piris, P. Yuan, L. Cai, et al. 2016. “Loss of cohesin complex components STAG2 or STAG3 confers resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma.” Nature medicine 22 (9): 1056-1061. doi:10.1038/nm.4155. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.4155. Published Version doi:10.1038/nm.4155 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:31731818 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nat Med Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2017 March 01. Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2016 September ; 22(9): 1056–1061. doi:10.1038/nm.4155. Loss of cohesin complex components STAG2 or STAG3 confers resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma Che-Hung Shen1, Sun Hye Kim1, Sebastian Trousil1, Dennie T. Frederick2, Adriano Piris3, Ping Yuan1, Li Cai1, Lei Gu4, Man Li1, Jung Hyun Lee1, Devarati Mitra1, David E. Fisher1,2, Ryan J. Sullivan2, Keith T. Flaherty2, and Bin Zheng1,* 1Cutaneous Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA 2Department of Medical Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, MA 3Department of Dermatology, Brigham & Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 4Division of Newborn Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. -

Low Tolerance for Transcriptional Variation at Cohesin Genes Is Accompanied by Functional Links to Disease-Relevant Pathways

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.037358; this version posted April 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title Low tolerance for transcriptional variation at cohesin genes is accompanied by functional links to disease-relevant pathways Authors William Schierdingǂ1, Julia Horsfieldǂ2,3, Justin O’Sullivan1,3,4 ǂTo whom correspondence should be addressed. 1 Liggins Institute, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2 Department of Pathology, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 3 The Maurice Wilkins Centre for Biodiscovery, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 4 MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton Acknowledgements This work was supported by a Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Grant to JH and JOS (16-UOO- 072), and WS was supported by the same grant. Contributions WS planned the study, performed analyses, and drafted the manuscript. JH and JOS revised the manuscript. Competing interests None declared. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.037358; this version posted April 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Variants in DNA regulatory elements can alter the regulation of distant genes through spatial- regulatory connections. -

C/Ebpα Is an Essential Collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-Mediated Leukemogenesis

C/EBPα is an essential collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis Cailin Collinsa, Jingya Wanga, Hongzhi Miaoa, Joel Bronsteina, Humaira Nawera, Tao Xua, Maria Figueroaa, Andrew G. Munteana, and Jay L. Hessa,b,1 aDepartment of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; and bIndiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Edited* by Louis M. Staudt, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved May 19, 2014 (received for review February 12, 2014) Homeobox A9 (HOXA9) is a homeodomain-containing transcrip- with Hoxa9. In addition, C/EBP recognition motifs are enriched tion factor that plays a key role in hematopoietic stem cell expan- at Hoxa9 binding sites. sion and is commonly deregulated in human acute leukemias. A C/EBPα is a basic leucine-zipper transcription factor that plays variety of upstream genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia a critical role in lineage commitment during hematopoietic dif- −/− (AML) lead to overexpression of HOXA9, almost always in associ- ferentiation (18). Whereas Cebpa mice show complete loss of ation with overexpression of its cofactor meis homeobox 1 (MEIS1). the granulocytic compartment, recent work shows that loss of α A wide range of data suggests that HOXA9 and MEIS1 play a syn- C/EBP in adult HSCs leads to both an increase in the number ergistic causative role in AML, although the molecular mechanisms of functional HSCs and an increase in their proliferative and leading to transformation by HOXA9 and MEIS1 remain elusive. In repopulating capacity (19, 20). Conversely, CEBPA overexpression can promote transdifferentiation of a variety of fibroblastic cells to this study, we identify CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/ the myeloid lineage and can induce monocytic differentiation in EBPα) as a critical collaborator required for Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated α MLL-fusion protein-mediated leukemias (21, 22). -

Test Summary Flyer-NGS Panels.Pub

Cancer‐related Mutaon Analysis Next Generaon Gene Sequencing for Myeloid Tesng Assay Summary IU Health Molecular Pathology Laboratory now offers high throughput sequencing for hot spot mutations found in clinically relevant cancer genes. In addition to a general panel of 54 genes, selected panels have been developed for a more tai- lored application in specific cancers. Comparing to single gene assay, these panels offer a more comprehensive and eco- nomic way to assess prognosis and/or treatment options for cancer patients at the initial diagnosis or at the relapse. Orderable Name: Use IU Health Molecular Pathology requisition; Call 317.491.6417 for requisition. Panels include: AML Mutations by NGS ASXL1, CEBPA, DNMT3A, ETV6/TEL, FLT3, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MLL, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, RUNX1, TET2, TP53, WT1 MDS Mutations by NGS ASXL1, ATRX, BCOR, BCORL1, ETV6/TEL, DNMT3A, EZH2, GNAS, IDH1, IDH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, ZRSR2 CML Mutations by NGS ABL1 MPN Mutations by NGS ASXL1, BRAF, CALR, CSF3R, EZH2, IKZF1, JAK2, JAK3, KDM6A, KIT, MPL, PDGRA, SETBP1, TET2 CMML Mutations by NGS ASXL1, CBL, CBLB, CBLC, EZH2, RUNX1, TET2, TP53, SRSF2 JMML Mutations by NGS CBL, CBLB, CBLC, HRAS, KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11 ALL Mutations by NGS ABL1, CSF3R, FBXW7, IKZF1, JAK3, KDM6A, NOTCH1 CLL Mutations by NGS MYD88, NOTCH1, SF3B1, TP53 Lymphoma/Myeloma Mutations by NGS BRAF, CDKN2A, CSF3R, FBXW7, HRAS, KRAS, MYD88, NOTCH1, NRAS, SF3B1,TP53 Hematopoietic Neoplasms Mutations by NGS ABL1, ASXL1, ATRX, BCOR, BCORL1, BRAF, CALR, CBL, CBLB, CBLC,CDKN2A, CEBPA, CSF3R, CUX1, DNMT3A, ETV6/TEL, EZH2, FBXW7, FLT3, GATA1, GATA2, GNAS, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, IKZF1,JAK2, JAK3, KDM6A, KIT, KRAS, MLL, MPL, MYD88, NOTCH1, NPM1, NRAS, PDGFRA, PHF6, PTEN, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1,SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC1A, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, WT1, ZRSR2 Clinical Utility: This test is useful for the assessment of prognosis and/or treatment options for cancer patients at the initial diagnosis or at the relapse. -

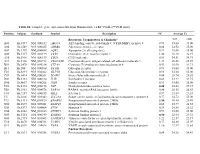

Table S1. Complete Gene Expression Data from Human Diabetes RT² Profiler™ PCR Array Receptors, Transporters & Channels* A

Table S1. Complete gene expression data from Human Diabetes RT² Profiler™ PCR Array Position Unigene GenBank Symbol Description FC Average Ct Receptors, Transporters & Channels* NGT GDM A01 Hs,5447 NM_000352 ABCC8 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 8 0.93 35.00 35.00 A04 0Hs,2549 NM_000025 ADRB3 Adrenergic, beta-3-, receptor 0.88 34.92 35.00 A07 Hs,1307 NM_000486 AQP2 Aquaporin 2 (collecting duct) 0.93 35.00 35.00 A09 30Hs,5117 NM_001123 CCR2 Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 1.00 26.28 26.17 A10 94Hs,5916 396NM_006139 CD28 CD28 molecule 0.81 34.51 34.71 A11 29Hs,5126 NM_001712 CEACAM1 Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 1.31 26.08 25.59 B01 82Hs,2478 NM_005214 CTLA4 (biliaryCytotoxic glycoprotein) T-lymphocyte -associated protein 4 0.53 30.90 31.71 B11 24Hs,208 NM_000160 GCGR Glucagon receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 C01 Hs,3891 NM_002062 GLP1R Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 C07 03Hs,6434 NM_000201 ICAM1 Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 0.84 28.74 28.89 D02 47Hs,5134 NM_000418 IL4R Interleukin 4 receptor 0.64 34.22 34.75 D06 57Hs,4657 NM_000208 INSR Insulin receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 E05 44Hs,4312 NM_006178 NSF N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor 0.48 28.42 29.37 F08 79Hs,2961 NM_004578 RAB4A RAB4A, member RAS oncogene family 0.88 20.55 20.63 F10 69Hs,7287 NM_000655 SELL Selectin L 0.97 23.89 23.83 F11 56Hs,3806 NM_001042 SLC2A4 Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 4 0.77 34.72 35.00 F12 91Hs,5111 NM_003825 SNAP23 Synaptosomal-associated protein, 23kDa 3.90 -

Genetic Testing for Acute Myeloid Leukemia AHS-M2062

Corporate Medical Policy Genetic Testing for Acute Myeloid Leukemia AHS-M2062 File Name: genetic_testing_for_acute_myeloid_leukemia Origination: 1/1/2019 Last CAP Review: 8/2021 Next CAP Review: 8/2022 Last Review: 8/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by large numbers of abnormal, immature myeloid cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood resulting from genetic changes in hematopoietic precursor cells which disrupt normal hematopoietic growth and differentiation (Stock, 2020). Related Policies: Genetic Cancer Susceptibility Using Next Generation Sequencing AHS-M2066 Molecular Panel Testing of Cancers to Identify Targeted Therapy AHS-M2109 Serum Tumor Markers for Malignancies AHS-G2124 Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) AHS- M2175 ***Note: This Medical Policy is complex and technical. For questions concerning the technical language and/or specific clinical indications for its use, please consult your physician. Policy BCBSNC will provide coverage for genetic testing for acute myeloid leukemia when it is determined to be medically necessary because the medical criteria and guidelines shown below are met. Benefits Application This medical policy relates only to the services or supplies described herein. Please refer to the Member's Benefit Booklet for availability of benefits. Member's benefits may vary according to benefit design; therefore member benefit language should be reviewed before applying the terms of this medical policy. When Genetic Testing for Acute Myeloid Leukemia is covered The use of genetic testing for acute myeloid leukemia is considered medically necessary for the following: A. Genetic testing for FLT3 internal tandem duplication and tyrosine kinase domain mutations (ITD and TKD), IDH1, IDH2, TET2, WT1, DNMT3A, ASXL1 and/or TP53 in adult and pediatric patients with suspected or confirmed AML of any type for prognostic and/or therapeutic purposes. -

Regulation of the C/Ebpα Signaling Pathway in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Review)

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 33: 2099-2106, 2015 Regulation of the C/EBPα signaling pathway in acute myeloid leukemia (Review) GUANHUA SONG1, LIn Wang2, Kehong BI3 and guosheng JIang1 1Department of hemato-oncology, Institute of Basic Medicine, shandong academy of Medical sciences, Key Laboratory for Modern Medicine and Technology of Shandong Province, Key Laboratory for Rare and Uncommon Diseases, Key Medical Laboratory for Tumor Immunology and Traditional Chinese Medicine Immunology of shandong Province, Jinan, Shandong 250062; 2Research Center for Medical Biotechnology, Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, Jinan, Shandong 250062; 3Department of Hematology, Qianfoshan Mountain Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250014, P.R. China Received December 2, 2014; Accepted January 26, 2015 DoI: 10.3892/or.2015.3848 Abstract. The transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding Contents protein α (C/EBPα), as a critical regulator of myeloid devel- opment, directs granulocyte and monocyte differentiation. 1. Introduction Various mechanisms have been identified to explain how 2. Function of C/EBPα in myeloid differentiation C/EBPα functions in patients with acute myeloid leukemia 3. Regulation of the C/EBPα signaling pathway (AML). C/EBPα expression is suppressed as a result of 4. Conclusion common leukemia-associated genetic and epigenetic altera- tions such as AML1-ETO, RARα-PLZF or gene promoter methylation. Recent data have shown that ubiquitination modi- 1. Introduction fication also contributes to its downregulation. In addition, 10-15% of patients with AML in an intermediate cytogenetic Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by uncon- risk subgroup were characterized by mutations of the C/EBPα trolled proliferation of myeloid progenitors that exhibit a gene. -

CEBPA Gene CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha

CEBPA gene CCAAT enhancer binding protein alpha Normal Function The CEBPA gene provides instructions for making a protein called CCAAT enhancer- binding protein alpha. This protein is a transcription factor, which means that it attaches ( binds) to specific regions of DNA and helps control the activity (expression) of certain genes. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha is involved in the maturation ( differentiation) of certain blood cells. It is also believed to act as a tumor suppressor, which means that it is involved in cellular mechanisms that help prevent the cells from growing and dividing too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Familial acute myeloid leukemia with mutated CEBPA At least six mutations in the CEBPA gene have been identified in families with familial acute myeloid leukemia with mutated CEBPA, which is a form of a blood cancer known as acute myeloid leukemia. These inherited mutations are present throughout a person' s life in virtually every cell in the body. The mutations result in a shorter version of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha. This shortened protein is produced from one copy of the CEBPA gene in each cell, and it is believed to interfere with the tumor suppressor function of the normal protein produced from the second copy of the gene. Absence of the tumor suppressor function of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha is believed to disrupt the regulation of blood cell production, leading to the uncontrolled production of abnormal cells that occurs in acute myeloid leukemia. In addition to the inherited mutation in one copy of the CEBPA gene in each cell, most individuals with familial acute myeloid leukemia with mutated CEBPA also acquire a mutation in the second copy of the CEBPA gene. -

Human Stromal Antigen 1 (STAG1) Cohesin Subunit SA-1 a Target Enabling Package (TEP)

Human Stromal Antigen 1 (STAG1) Cohesin Subunit SA-1 A Target Enabling Package (TEP) Gene ID / UniProt ID / EC 10274 / Q8WVM7 Target Nominator Mark Petronczki (Boerhinger-Ingelheim) SGC Authors Joseph Newman, Vittorio Katis, Opher Gileadi Collaborating Authors Mark Petronczki1 Target PI Opher Gileadi (SGC Oxford) Therapeutic Area(s) Cancer Disease Relevance STAG1 is essential for survival of cancer cells lacking the paralogue gene STAG2 Date Approved by TEP Evaluation June 10 2019 Group Document version Version 1 Document version date October 2020 Citation 10.5281/zenodo.3245308 Affiliations 1. Boehringer-Ingelheim. USEFUL LINKS (Please note that the inclusion of links to external sites should not be taken as an endorsement of that site by the SGC in any way) SUMMARY OF PROJECT Loss of function mutations in the cohesin subunit gene STAG2 are common in a variety of cancers (1). These cells become dependent on the paralogous cohesin subunit STAG1 (2-4). Mutants of STAG1 that disrupt the binding to the cohesin subunit RAD21 cannot complement the loss of STAG2. This TEP examines the druggability of STAG1 as a synthetic lethal strategy to treat stag2 - cancers. The TEP includes crystal structures of two domains of STAG1, alone and in complex with Rad21-rderived peptides. We performed screens of a fragment library and identified small molecules bound to pockets in the two domains of STAG1. We also developed assays for binding of RAD21 peptides to STAG1, which can be used to screen for molecules that disrupt binding. For more information regarding any aspect of TEPs and the TEP programme, please contact [email protected] 1 SCIENTIFIC BACKGROUND Cohesins are ring-shaped multiprotein complexes that encircle chromosomes from G1 to late anaphase, holding together sister chromatids and ensuring proper chromosomal segregation during mitosis (1,5,6). -

The Polymorphism Rs944289 Predisposes to Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Through a Large Intergenic Noncoding RNA Gene of Tumor Suppressor Type

The polymorphism rs944289 predisposes to papillary thyroid carcinoma through a large intergenic noncoding RNA gene of tumor suppressor type Jaroslaw Jendrzejewskia, Huiling Hea, Hanna S. Radomskaa, Wei Lia, Jerneja Tomsica, Sandya Liyanarachchia, Ramana V. Davulurib, Rebecca Nagya, and Albert de la Chapellea,1 aHuman Cancer Genetics Program, Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210; and bMolecular and Cellular Oncogenesis Program, Center for Systems and Computational Biology, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Contributed by Albert de la Chapelle, April 4, 2012 (sent for review February 20, 2012) A genome-wide association study of papillary thyroid carcinoma (GWAS) have addressed the predisposition to PTC (11–13). (PTC) pinpointed two independent SNPs (rs944289 and rs965513) Gudmundsson et al. (11) studied Icelandic PTC patients and located in regions containing no annotated genes (14q13.3 and controls, followed by validation in Spanish and US cases and 9q22.33, respectively). Here, we describe a unique, long, inter- controls. Two SNPs that showed highly significant association Papillary Thyroid genic, noncoding RNA gene (lincRNA) named with PTC were detected (rs965513 and rs944289). The variants Carcinoma Susceptibility Candidate 3 PTCSC3 ( ) located 3.2 kb were located in 9q22.33 and 14q13.3, respectively, and have been downstream of rs944289 at 14q.13.3 and the expression of which confirmed by other research groups (14, 15). As both SNPs were is strictly thyroid specific. By quantitative PCR, PTCSC3 expression − located in gene-poor regions, no immediate candidate genes was strongly down-regulated (P = 2.84 × 10 14) in thyroid tumor tissue of 46 PTC patients and the risk allele (T) was associated with presented themselves as being affected by or associated with the the strongest suppression (genotype [TT] (n = 21) vs.