Efficacy of Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate in Adults with Attention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

Stimulant and Related Medications: US Food and Drug

Stimulant and Related Medications: U.S. Food and Drug Administration-Approved Indications and Dosages for Use in Adults The therapeutic dosing recommendations for stimulant and related medications are based on U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved product labeling. Nevertheless, the dosing regimen is adjusted according to a patient’s individual response to pharmacotherapy. The FDA-approved dosages and indications for the use of stimulant and related medications in adults are provided in this table. All medication doses listed are for oral administration. Information on the generic availability of the stimulant and related medications can be found by searching the Electronic Orange Book at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/default.cfm on the FDA website. Generic Medication Indication Dosing Information Other Information Availability amphetamine/dextroamphetamine ADHD Initial dose: May increase daily dose by 5 mg at Yes mixed salts[1] 5 mg once or twice a day; weekly intervals until optimal response Maximum dose: 40 mg per day is achieved. Only in rare cases will it be necessary to exceed a total of 40 mg per day. amphetamine/dextroamphetamine narcolepsy Initial dose: 10 mg per day; May increase daily dose by 10 mg at Yes mixed salts Usual dose: weekly intervals until optimal response 5 mg to 60 mg per day is achieved. Take first dose in divided doses upon awakening. amphetamine/dextroamphetamine ADHD Recommended dose: Patients switching from regular-release Yes mixed salts ER*[2] 20 mg once a day amphetamine/dextroamphetamine mixed salts may take the same total daily dose once a day. armodafinil[3] narcolepsy Recommended dose: Take as a single dose in the morning. -

Established Aggregate Production Quotas for Schedule I and II

59980 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 190 / Monday, October 1, 2012 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE for Schedule I and II Controlled information, DEA has determined that Substances and Proposed Assessment of adjustments to the proposed aggregate Drug Enforcement Administration Annual Needs for the List I Chemicals production quotas and assessment of [Docket No. DEA–365] Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and annual needs for 3,4-methylenedioxy-N- Phenylpropanolamine for 2013,’’ was methylcathinone (methylone), Established Aggregate Production published in the Federal Register (77 3,4,methylenedioxypyrovalerone Quotas for Schedule I and II Controlled FR 46519). That notice proposed the (MDPV), 4-methyl-N-methylcathinone Substances and Established 2013 aggregate production quotas for (mephedrone), N-benzylpiperazine, Assessment of Annual Needs for the each basic class of controlled substance amphetamine (for conversion), List I Chemicals Ephedrine, listed in schedules I and II and the 2013 amphetamine (for sale), hydrocodone Pseudoephedrine, and assessment of annual needs for the list (for sale), hydromorphone, Phenylpropanolamine for 2013 I chemicals ephedrine, lisdexamfetamine, methylphenidate, pseudoephedrine, and morphine (for sale), oxycodone (for AGENCY: Drug Enforcement phenylpropanolamine. All interested sale), oxymorphone (for conversion), Administration (DEA), Department of persons were invited to comment on or remifentanil, sufentanil, tapentadol, Justice. object to the proposed aggregate ephedrine (for conversion), ephedrine ACTION: -

A Dose-Escalating, Phase-2 Study of Oral Lisdexamfetamine

Ezard et al. BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:428 DOI 10.1186/s12888-016-1141-x STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Study protocol: a dose-escalating, phase-2 study of oral lisdexamfetamine in adults with methamphetamine dependence Nadine Ezard1,2, Adrian Dunlop3, Brendan Clifford1* , Raimondo Bruno4, Andrew Carr5, Alexandra Bissaker1 and Nicholas Lintzeris6,7 Abstract Background: The treatment of methamphetamine dependence is a continuing global health problem. Agonist type pharmacotherapies have been used successfully to treat opioid and nicotine dependence and are being studied for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. One potential candidate is lisdexamfetamine, a pro-drug for dexamphetamine, which has a longer lasting therapeutic action with a lowered abuse potential. The purpose of this study is to determine the safety of lisdexamfetamine in this population at doses higher than those currently approved for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or binge eating disorder. Methods/design: This is a phase 2 dose escalation study of lisdexamfetamine for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Twenty individuals seeking treatment for methamphetamine dependence will be recruited at two Australian drug and alcohol services. All participants will undergo a single-blinded ascending-descending dose regime of 100 to 250 mg lisdexamfetamine, dispensed daily on site, over an 8-week period. Participants will be offered counselling as standard care. For the primary objectives the outcome variables will be adverse events monitoring, drug tolerability and regimen completion. Secondary outcomes will be changes in methamphetamine use, craving, withdrawal, severity of dependence, risk behaviour and other substance use. Medication acceptability, potential for non-prescription use, adherence and changes in neurocognition will also be measured. -

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH VYVANSE®* lisdexamfetamine dimesylate Capsules: 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 50 mg, 60 mg and 70 mg Chewable Tablets: 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 50 mg and 60 mg Central Nervous System Stimulant Takeda Canada Inc. Date of Preparation: 22 Adelaide Street West, Suite 3800 19 February 2009 Toronto, Ontario M5H 4E3 Date of Revision: July 21, 2020 Submission Control No.: 240669 *VYVANSE® and the VYVANSE Logo are registered trademarks of Shire LLC, a Takeda company. Takeda and the Takeda Logo are trademarks of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, used under license. © 2020 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. All rights reserved. Pa ge 1 of 60 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ................................................................... 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ........................................................................ 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ............................................................................................ 5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ............................................................................ 6 ADVERSE REACTIONS........................................................................................... 12 DRUG INTERACTIONS ........................................................................................... 23 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ........................................................................ 25 OVERDOSAGE ....................................................................................................... -

Amphetamine Use Among Workers with Severe Hyperthermia

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Notes from the Field Amphetamine Use Among Workers with Severe National Weather Service observation stations, the maximum Hyperthermia — Eight States, 2010–2019 outdoor heat index (a metric that combines temperature and Andrew S. Karasick, MD1,2; Richard J. Thomas, MD1; relative humidity into a single number that represents how hot Dawn L. Cannon, MD1; Kathleen M. Fagan, MD1; Patricia A. Bray, MD1; the conditions feel to humans) ranged from 86°F to 107°F 1 1 Michael J. Hodgson, MD ; Aaron W. Tustin, MD (median = 97°F) on the days of the nine incidents. Seven of the nine workers died, and two survived life-threat- Workers can develop hyperthermia when core body tem- ening illnesses. Peak body temperature ranged from 103°F to perature rises because of heat stress (environmental heat plus 110.6°F (39.4°C to 43.7°C) in eight workers with confirmed metabolic heat from physical activity) (1). Amphetamines are severe hyperthermia. In one fatality with no premortem body central nervous system stimulants that can induce hyperthermia temperature measurement, the medical examiner suspected independently or in combination with other risk factors (2). that hyperthermia was a significant contributing condition, During 2010–2016, the Directorate of Technical Support and based upon the circumstances (i.e., death occurred in a hot Emergency Management’s Office of Occupational Medicine environment after strenuous activity on a hot day) and lack and Nursing (OOMN), at the Occupational Safety and Health of anatomic evidence of an alternative cause of death (e.g., Administration (OSHA), identified three workers with fatal myocardial infarction). -

Pharmacy Prior Authorization Guideline 1. Criteria

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care – Pharmacy Prior Authorization Guideline Guideline Name ADHD Medications: Adderall (amphetamine-dextroamphetamine mixed salts), Adderall XR (amphetamine-dextroamphetamine mixed salts extended-release), Adzenys ER (amphetamine), Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine), Aptensio XR (methylphenidate), amphetamine, amphetamine-dextroamphetamine mixed salts, amphetamine-dextroamphetamine mixed salts extended-release, Concerta (methylphenidate), Cotempla-XR ODT (methylphenidate), Daytrana (methylphenidate), Desoxyn (methamphetamine), Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), dexmethylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate extended- release, dextroamphetamine, dextroamphetamine extended-release, dextroamphetamine oral solution, Dyanavel XR (amphetamine), Evekeo (amphetamine), Focalin (dexmethylphenidate), Focalin XR (dexmethylphenidate), Jornay PM (methylphenidate), Metadate ER (methylphenidate), methamphetamine, Methylin oral solution (methylphenidate), methylphenidate, methylphenidate chewable tablets, methylphenidate extended-release, methylphenidate extended-release (CD), methylphenidate extended-release (LA), methylphenidate extended- release OSM, methylphenidate oral solution, Mydayis (amphetamine- dextroamphetamine), Procentra (dextroamphetamine), Quillivant XR (methylphenidate), Quillichew ER (methylphenidate), Relexxii (methylphenidate), Ritalin (methylphenidate), Ritalin LA (methylphenidate), Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine), and Zenzedi (dextroamphetamine) 1. Criteria Product Name: Brand Adderall, Generic amphetamine-dextroamphetamine mixed -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau Et Al

US 20150202317A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 23, 2015 (54) DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS Publication Classification FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A647/48 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: Ascendis Pharma A/S, Hellerup (DK) A638/26 (2006.01) A6M5/9 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Harald Rau, Heidelberg (DE); Torben A 6LX3/553 (2006.01) Le?mann, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse (52) U.S. Cl. (DE) CPC ......... A61K 47/48338 (2013.01); A61 K3I/553 (2013.01); A61 K38/26 (2013.01); A61 K (21) Appl. No.: 14/674,928 47/48215 (2013.01); A61M 5/19 (2013.01) (22) Filed: Mar. 31, 2015 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to a prodrug or a pharmaceuti Related U.S. Application Data cally acceptable salt thereof, comprising a drug linker conju (63) Continuation of application No. 13/574,092, filed on gate D-L, wherein D being a biologically active moiety con Oct. 15, 2012, filed as application No. PCT/EP2011/ taining an aliphatic amine group is conjugated to one or more 050821 on Jan. 21, 2011. polymeric carriers via dipeptide-containing linkers L. Such carrier-linked prodrugs achieve drug releases with therapeu (30) Foreign Application Priority Data tically useful half-lives. The invention also relates to pharma ceutical compositions comprising said prodrugs and their use Jan. 22, 2010 (EP) ................................ 10 151564.1 as medicaments. US 2015/0202317 A1 Jul. 23, 2015 DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS 0007 Alternatively, the drugs may be conjugated to a car FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING rier through permanent covalent bonds. -

ATC) Codes and Drug Identification Numbers (Dins

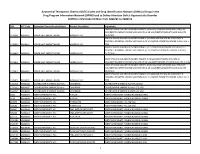

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Codes and Drug Identification Numbers (DINs) of Drugs in the Drug Program Information Network (DPIN) Used to Define Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Manitoba Children from 2000/01 to 2009/10 DIN ATC Code Equivalent Generic Product Name Product Description Ingredients AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (1.25 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (1.25 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (1.25 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE 2248808 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR (1.25 MG) AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (2.5 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (2.5 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (2.5 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE (2.5 2248809 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR MG) AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (3.75 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (3.75 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (3.75 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE 2248810 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR (3.75 MG) AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (5 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (5 2248811 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (5 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE (5 MG) AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (6.25 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (6.25 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (6.25 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE 2248812 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR (6.25 MG) AMPHETAMINE ASPARTATE MONOHYDRATE (7.5 MG)/AMPHETAMINE SULFATE (7.5 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SACCHARATE (7.5 MG)/DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE (7.5 2248813 N06BA01 MIXED SALT AMPHETAMINE ADDERALL XR MG) 1924516 N06BA02 DEXTROAMPHETAMINE SULFATE DEXEDRINE DEXTROAMPHETAMINE -

The Pharmacology of an Agonist Medication to Treat Stimulant Use Disorder

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 The Pharmacology of an Agonist Medication to Treat Stimulant Use Disorder Amy Johnson johnsonar24 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd © Amy Johnson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5177 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Amy R. Johnson 2017 All Rights Reserved The Pharmacology of an Agonist Medication to Treat Stimulant Use Disorder A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University by Amy R. Johnson Bachelor of Science, University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire, 2013 Advisor: S. Stevens Negus, PhD Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, VA November, 2017 Acknowledgements Thank you to all the people who made this dissertation possible. I would like to thank my family for their support and belief in me. Many thanks to my dissertation advisor, Steve Negus, for his guidance, knowledge, patience, and encouragement. Thank you to Katherine Nicholson and Matthew Banks, each of whom guided me through a different procedure through the course of my research and served on my committee. Thanks to my remaining committee members, Lori Keyser-Marcus and Jose Eltit, for their time and commitment to my project. Thank you to my entire committee for helping to develop and mold me as a scientist. -

2016-2018 Stimulant Overdose Surveillance Preliminary Report

Stimulant Overdose Surveillance Preliminary Report Georgia 2016-2018 Drug Surveillance Unit Epidemiology Section Georgia Department of Public Health https://dph.georgia.gov/drug-overdose-surveillance-unit Stimulant Overdose Surveillance Report, Georgia, 2018 / Page 1 Stimulant Overdose Surveillance, Georgia, 2018 The purpose of this report is to describe fatal (mortality) and nonfatal (morbidity) stimulant-involved hospitalizations and deaths in Georgia during 2016, 2017, and 2018, including those involving prescription stimulants (e.g. Adderall, Ritalin, etc.), and illicit stimulants (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, etc.). Stimulant overdose data was analyzed by the Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH) Epidemiology Program, Drug Surveillance Unit, using Georgia hospital discharge inpatient and emergency department (ED) visit data, and DPH Vital Records death data. Key Findings Stimulant-involved morbidity and mortality is increasing in Georgia. Mortality • From 2016 to 2018, overdose deaths involving stimulants increased by 44%, from 487 to 703 deaths. • From 2017 to 2018, overdose deaths involving stimulants increased by 11%, from 631 to 703 deaths. • In 2018, amphetamines were involved in more deaths than any other stimulant. • White persons were 1.6 times more likely to die from a drug overdose involving stimulants and 5.5 times more likely to die from a drug overdose involving amphetamines than Black persons, yet Black persons were 1.5 times more likely than white persons to die from a drug overdose involving cocaine. • Males aged 25-64 years died more frequently from stimulant-involved overdose than males in any other age category and females of all age categories. Males aged 35-44 years had the highest stimulant-related death rate. -

DRUGS POTENTIALLY AFFECTING MIBG UPTAKE Rev. 26 Oct 2009

DRUGS POTENTIALLY AFFECTING MIBG UPTAKE rev. 26 Oct 2009 EXCLUDED MEDICATIONS DUE TO DRUG INTERACTIONS WITH ULTRATRACE I-131-MIBG Drug Class Generic Drug Name Within Class Branded Name Checked Cocaine Cocaine □ Dexmethylphenidate Focalin, Focalin XR □ CNS Stimulants (Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor) Methylphenidate Concerta, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, □ Ritalin-SR, Daytrana benzphetamine Didrex □ Diethylpropion Tenuate, Tenuate Dospan □ Phendimetrazine Adipost, Anorex-SR, Appecon, Bontril PDM, Bontril Slow Release, Melfiat, Obezine, CNS Stimulants (Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor) □ Phendiet, Plegine, Prelu-2, Statobex Phenteramine Adipex-P, Ionamin, Obenix, Oby-Cap, Teramine, Zantryl □ Sibutramine Meridia □ Isocarboxazid Marplan □ Linezolid Zyvox □ Phenelzine Nardil □ Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors selegiline (MAOa at doses > 15 mg qd) Eldepryl, Zelapar, Carbex, Atapryl, Jumex, Selgene, Emsam □ Tranylcypromine Parnate □ Reserpine Generic only. No brands available. Central Monoamine Depleting Agent □ labetolol Non-select Beta Adrenergic Blocking Agents Normodyne, Trandate □ Opiod Analagesic Tramadol Ultram, Ultram ER □ Pseudoephedrine Chlor Trimeton Nasal Decongestant, Contac Cold, Drixoral Decongestant Non- Drowsy, Elixsure Decongestant, Entex, Genaphed, Kid Kare Drops, Nasofed, Sympathomimetics : Direct Alpha 1 Agonist (found in cough/cold preps) Seudotabs, Silfedrine, Sudafed, Sudodrin, SudoGest, Suphedrin, Triaminic Softchews □ Allergy Congestion, Unifed amphetamine (various