Eligibility/Feasibility Study, Environmental Assessment For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

HISTORY of the TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST a Compilation

HISTORY OF THE TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST A Compilation Posting the Toiyabe National Forest Boundary, 1924 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bridgeport and Carson Ranger District Centennial .................................................................... 126 Forest Histories ........................................................................................................................... 127 Toiyabe National Reserve: March 1, 1907 to Present ............................................................ 127 Toquima National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ....................................................... 128 Monitor National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ........................................................ 128 Vegas National Forest: December 12, 1907 – July 2, 1908 .................................................... 128 Mount Charleston Forest Reserve: November 5, 1906 – July 2, 1908 ................................... 128 Moapa National Forest: July 2, 1908 – 1915 .......................................................................... 128 Nevada National Forest: February 10, 1909 – August 9, 1957 .............................................. 128 Ruby Mountain Forest Reserve: March 3, 1908 – June 19, 1916 .......................................... -

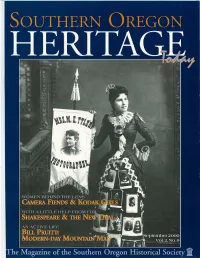

Link to Magazine Issue

----.. \\U\.1, fTI!J. Shakespeare and the New Deal by Joe Peterson ver wonder what towns all over Band, William Jennings America would have missed if it Bryan, and Billy Sunday Ehadn't been for the "make work'' was soon reduced to a projects of the New Deal? Everything from walled shell. art and research to highways, dams, parks, While some town and nature trails were a product of the boosters saw the The caved-in roofof the Chautauqua building led to the massive government effort during the decapitated building as a domes' removal, andprompted Angus Bowmer to see 1930s to get Americans back to work. In promising site for a sports possibilities in the resulting space for an Elizabethan stage. Southern Oregon, add to the list the stadium, college professor Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which got its Angus Bowmer and start sixty-five years ago this past July. friends had a different vision. They "giveth and taketh away," for Shakespeare While the festival's history is well known, noticed a peculiar similarity to England's play revenues ended up covering the Globe Theatre, and quickly latched on to boxing-match losses! the idea of doing Shakespeare's plays inside A week later the Ashland Daily Tidings the now roofless Chautauqua walls. reported the results: "The Shakespearean An Elizabethan stage would be needed Festival earned $271, more than any other for the proposed "First Annual local attraction, the fights only netting Shakespearean Festival," and once again $194.40 and costing $206.81."4 unemployed Ashland men would be put to By the time of the second annual work by a New Deal program, this time Shakespeare Festival, Bowmer had cut it building the stage for the city under the loose from the city's Fourth ofJuly auspices of the WPA.2 Ten men originally celebration. -

From the Editors Trail Turtles Head North

Newsletter of the Southwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association January, 2005 From the Editors Trail Turtles Head North In this newsletter we give the The SWOCTA Trail Turtles report of the SWOCTA Trail Turtles‟ played hooky from the southern trails Fall 2004 trip on the Applegate Trail. this fall. Don Buck and Dave Hollecker The Turtles made extensive use of the offered to guide the Turtles over the recently published Applegate Trail Applegate Trail from Lassen Meadows Guide (see the advertisement on the back to Goose Lake. In a way, it could be said cover of this issue). The Turtles felt that we were still on a southern trail, as “appreciation for those who … have the Applegate Trail was also known as spent long hours researching and finding the Southern Trail to Oregon when it … this trail that [has] been waiting to first opened. again be part of the … historical record.” After learning of the ruggedness We hope that the Turtles‟ ongoing of the trip, and with the knowledge there efforts to map the southwestern emigrant would be no gas, food or ice for 300 trails also will lead to a guidebook, for miles, everyone loaded up appropriately. which future users will feel a similar The number of vehicles was limited to appreciation. eight to facilitate time constraints and We (the “Trail Tourists”) also lack of space in some parking and include a record of our recent trip to camping areas. Fourteen people explore the Crook Wagon Road. attended. Unfortunately, we received our copy of the new guidebook, General Crook Road in Arizona Territory, by Duane Hinshaw, only after our trip. -

The Story of Susan's Bluff and Susan

A Working Organization Dedicated to Marking the California Trail FALL 2011 The Story of Susan’s Bluff and Susan Story by Denise Moorman Photos by Jim Moorman and Larry Schmidt It’s 1849 on the Carson Trail. Emigrant wagon trains and 49ers are winding their way through the newly acquired Upper California territory (western Nevada) on their way to the goldfields, settlements and cities of California. One of the many routes through running through this area follows along the Carson River between the modern Fort Churchill Historic Site and the town of Dayton. Although not as popular as the faster Twenty-Six Mile Desert cutoff, which ran roughly where U.S. Highway 50 goes today, the Carson River route provided valuable feed and water for the stock the New Trails West Marker, CR-20 at Susan’s Bluff. pioneers still had. Along this route the wagon trains hugged the left bank of the Carson until they Viewed from the direction the emigrants were reached a steep bluff jutting out almost to the river. approaching, the bluff hides behind other ridges Although foot traffic could make it around the point until you are past it. However, looking back, it of the bluff, wagons had to ford the river before they looms powerfully against the sky. This makes one reached it. Trails West recently installed the last wonder how something so imposing came to be Carson Route marker, Marker CR-20, near this ford known as “Susan’s Bluff?” continued on page 4 at the base of the cliff known as Susan’s Bluff. -

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent's Annual

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent’s Annual Report Aaron Mahr, Superintendent P.O. Box 728 Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87504 Dedication for new wayside exhibits and highway signs for the Santa Fe National Historic Trail through Cimarron, New Mexico Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Administration and Stafng Organization and Purpose Budgets Staf NTIR Funding for FY11 4 Core Operations Partnerships and Programs Feasibility Studies California and Oregon NHTs El Camino Real de los Tejas NHT El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro NHT Mormon Pioneer NHT Old Spanish NHT Pony Express NHT Santa Fe NHT Trail of Tears NHT 23 NTIR Trails Project Summary Challenge Cost Share Program Summary ONPS Base-funded Projects Projected Supported with Other Funding 27 Content Management System 27 Volunteer-in-Parks 28 Geographic Information System 30 Resource Advocacy and Protection 32 Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program Route 66 Cost Share Grant Program 34 Tribal Consultation 35 Summary Acronym List BEOL - Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site BLM - Bureau of Land Management CALI - California National Historic Trail CARTA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association CAVO - Capulin Volcanic National Monument CCSP - Challenge Cost Share Program CESU - Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit CMP/EA - comprehensive management plan/environmental assessment CTTP - Connect Trails to Parks DOT - Department of Transportation EA - environmental assessment ELCA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail ELTE - El Camino -

Barrel Springs Backcountry Byway

U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Land Management Surprise Valley Barrel Springs Back Country Byway A Self-Guided Tour Welcome to the road less traveled! Few people get to experience the beautiful mountains and valley you see on the front cover. This brochure and map will tell you how to find and explore Surprise Valley- how it got its name, the history of the emigrants who ventured west in 1849, and the geological wonders that have shaped this landscape. A map showing the location of Cedarville and major highways in the area Getting There: From U.S. Hwy. 395 in California, five miles north of Alturas, Modoc County, take California Hwy. 299 east to Cedarville, California. From Interstate 80 at Wadsworth in Nevada, 30 miles east of Reno, take Nevada Hwy. 447 north through Gerlach, 141 miles to Cedarville, California. 2 SURPRISE VALLEY-BARREL SPRINGS BACK COUNTRY BYWAY A SELF-GUIDED TOUR Pronghorn antelope with Mount Bidwell in the background 3 CONTENTS 1. THE SECRET VALLEY…...……..1 2. BYWAY LOOP MAP……………..10 3. BYWAY DRIVING TOUR……....12 4. VISITOR TIPS……………………....28 5. WILDFLOWER GUIDE…….......30 Lake City Flouring Mill circa 1900 4 THE SECRET VALLEY The Warner Mountains soar up from the valley floor like a scene from an Ansel Adams photograph. In the valley, coveys of quail trickle across the quiet streets in little towns. At twilight, herds of mule deer join cattle and sheep in the green fields. There are no stoplights, no traffic, and no sirens. This is where the paved road ends. This place, Surprise Valley, is so removed, so distinct from the rest of California, that you, like others, may come to find that it is the Golden State’s best kept secret. -

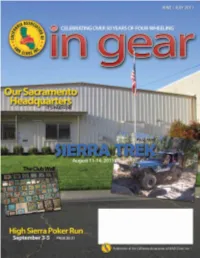

In-Gear-Jun-Jul-11.Pdf

2 In Gear / June-July 2011 / cal4wheel.com CA4WDC, INC. Bonnie Steele, Office Manager 8120 36th Ave. WHAT’S Sacramento, CA 95824-2304 (916) 381-8300 INSIDE Fax (916) 381-8726 [email protected] www.cal4wheel.com IN GEAR OFFICE President’s Message 7 Suzy Johnson, Editor CA4WDC Contacts 6 222 Rainbow Dr. #12269 District Meetings 4 Livingston, TX 77399-2022 VP Reports 8-10 (805) 550-2804 Natural Resource Consultants 11-12 Fax (866) 888-2465 Donations 13 [email protected] Sierra Trek 16-17 www.cal4wheel.com High Sierra Poker Run 20-21 Not everyone drives a Jeep 22 What is the CA4WDC? Jeff Knoll goes to Washington 23 The California Association of Hi Landers renovate campground 24 Four Wheel Drive Clubs, Inc. (founded in 1959) is a non- The ‘Other’ Rubicon 25 profit organization comprised Sweepstakes Vehicle 26-27 of member clubs, individuals Club Directory 28-29 and business firms, united in a common objective — the betterment of Calendar 30 vehicle-oriented outdoor recreation. Gearbox Directory 30 We represent four wheelers, Associate Members 31 hunters, fishermen, and other outdoor recreationalists. Ours is the largest organization of its type in California. THROUGH A UNITED EFFORT WE: ON THE COVER: The CA4WDC headquarters building features many displays honoring our clubs, award winners, previous board members, and more. Photo • Promote responsible use of public lands. by Bonnie Steele. Inset photo by Will Corbett of his son Wade on Winch Hill 5 at • Prevent legislation that would restrict off- the 2008 Sierra Trek. road vehicles and vehicle use. • Develop programs of conservation, JUNE-JULY 2011 / VOLUME 52 #1 education and safety. -

The End of the Line Changes to the Trail California National Historie

California National Historie Trail The California Nat ional Historie Trai l spans 2,000 miles across the United States. lt brought em igrants, gold-seekers, merchants, and others west to California in the l 800s. The Bu reau of Land Management in California manages four segments, nearly 140-miles of the trail, the Appl egate, the Lassen, the Nobles, and the Yreka . Set ee n 1841 and 1869, more than 250,000 emigrants traversed the Cal ifornia Trail. Lured by gold, farmland and a promise of paradise in California, mid l 9th century emigrants used the Ca lifornia a 1onal Historie Tra il for a migration route to the west. umerous routes emerged in attempts to create the best available course. Today, this t rail offer s auto ouring, educa ional programs and vi siter centers to present-day gold seekers arid explorers. ln 1992, Congress designated the Californ ia Trail system as a National Historie Trail. ln 2000, it also became part of the ln April of 1852, William H. Nobles Bureau of Land anagement's system of National Conservation Lands. This is a 36 million-acre collection of treasured landscapes conserved by the Bureau of La nd Management. Find out more at www bl gov/ programs/ national Z:6Z:E-LSZ: (OES) placed a notice in the Shasta Courier Changes to the Trail conservation-lands. Of: L96 V'J 'a ll!Auesns announcing a meeting in Shasta +aaJ+S Mopay+eaM S L L The original route runs from Black Roc Springs, wnasnl/\l 1e::> !JO+S! H uasse1 Ala!OOS 1eo!JOlS!H A}uno~ uasse1 City, where he would reveal his newly Nevada to Shasta City, California and as used mainly w+y ·xapu1/ 0Ael/Ao5·sdu-MMM discovered wagon route, which later from 1852 to 1869. -

The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon ‘

Emigrant Lake County Park California National Historic Trail Hugo Neighborhood Association and Historical Society Jackson County Parks National Park Service The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon ‘ The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the “Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children drowning, were seized with Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats and were about to make a desperate attempt to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’” brothers along with others vowed to look for an all- -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse land route into Oregon from Idaho for future settlers. “Our hearts are broken. As soon as our families are settled and time can be spared we must look for another way that avoids the river.” -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. An Umpqua Indian showed them a foot trail that crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then on to Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. They next turned east and went over the Cascade Mountains to the Klamath Basin. The party devised pathways through canyons and mountain passes, connecting the trail south from the Willamette Valley with the existing California Trail to Fort Hall, Idaho. In August 1846, the first emigrants to trek the new southern road left Fort Hall. -

"West of the Cascades" KLAMATH ECHOES

1776 BICENTENNIAL 1976 APPLEGATE TRAIL II "West of the Cascades" KLAMATH ECHOES Sanctioned by Klamath County Historical Society NUMBER 14 OREGON OR BUST • • ' A covered wagon along the Oregon Trail in Western Nebraska near the South Platte River emigrant Crossing. (Photo by Helen Helfrich) FORGOTTEN TRAILS Strange, is it not? That of the myriads who Before us pass'd the door of Darkness through Not one returns to tell us of the Trail, Which to discover we must travel, too. Apologies to Omar Khayyam. Hannah Ann (Davis) Hendricks (Courtesy Fred Elvin Inlow) DEDICATION We respectfully dedicate this, the fourteenth issue of Klamath Echoes, to Hanna Ann Davis, 14 years of age in 1847. She came west across the plains with her father, three brothers and four sisters, her mother having died en route. Traveling the Oregon- California and Applegate Trails, they arrived at Fandango Valley, east of Goose Lake in extreme Northeastern California on September 29, 1847. While Hanna Ann was preparing the evening meal, three arrows were fired into the camp by Indians hiding in the nearby brush. Two of the arrows struck Hanna Ann. One passed through the calf of her leg and the other through her arm and into her side. She fell into the fire and was severely burned. According to Lester G. Hulin, the 1847 diarist, three days later Hanna Ann was still unable to ride in a wagon and "had to be carried by a stage [stretcher?]. Only recently have we learned (from information furnished by Fred Elvin Inlow, Medford, Oregon, a distant relative) that Hanna Ann survived, later married, and raised a family of ten children.