Welfare of Zebra Finches Used in Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

The Zebra Finch Genome and Avian Genomics in the Wild

Review CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/emu Emu, 2010, 110, 233–241 The Zebra Finch genome and avian genomics in the wild Christopher N. Balakrishnan A,C, Scott V. Edwards B and David F. Clayton A ADepartment of Cell and Developmental Biology and Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL 61820, USA. BMuseum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata) is the first species of passerine bird with a complete genome sequence, making it an exciting time for avian evolutionary biology. Native to Australia and the Lesser Sunda Islands, this species has long played an important role in the study of ecology, behaviour and neuroscience. With the sequencing of its genome, the Zebra Finch now also represents an important model system for evolutionary and population genomics. The production of a genome sequence for the Zebra Finch will have far-reaching impacts on the study of avian biology. Here we discuss the genomic resources available for the Zebra Finch, including the genome sequence itself, and some of the ways in which they will facilitate the study of avian diversity. We also highlight recent examples from the literature that have already begun to leverage Zebra Finch genomic tools towards the study of birds in nature. Introduction in a comparative context, highlighting some of the ways in The Zebra Finch genome is the first passerine genome to be which the Zebra Finch genome can facilitate evolutionary sequenced and only the second avian genome to be sequenced studies across the passerine radiation. -

Vocal Communication in Zebra Finches: a Focused Description of Pair Vocal Activity

Vocal communication in zebra finches: a focused description of pair vocal activity Dissertation Fakultät für Biologie Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München durchgeführt am Max-Planck-Institut für Ornithologie Seewiesen vorgelegt von Pietro Bruno D’Amelio München, 2018 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Manfred Gahr Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Niels Dingemanse Eingereicht am: 06.03.2018 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.05.2018 Diese Dissertation wurde unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. Manfred Gahr und Dr. Andries ter Maat angefertigt. i ii Table of Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... iv General Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Vocal communication ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodological challenges and how they were approached .................................................................... 8 Vocal individual recognition ................................................................................................................... 10 Pair communication ................................................................................................................................ 11 References .................................................................................................................................................. -

Download Complete

HISTORICAL AND SEASONAL CHANGES IN THE COMMUNITY OF FOREST BIRDS AT LONGNECK LAGOON NATURE RESERVE, SCHEYVILLE, NEW SOUTH WALES K. H. EGAN,1 J. R. FARRELL2 and D. L. PEPPER-EDWARDS3 11 Bowman Street, Mortdale, New South Wales 2223 273 Ellison Road, Springwood, New South Wales 2777 321 Arthur Street, Hornsby, New South Wales 2077 Received: 12 October, 1995 Observations dating back to 1937, banding data accumulated from 1965 to 1994 and census data collected from 1992 to 1995 have been used to show the changes in a community of forest birds at Longneck Lagoon Nature Reserve on an historical and seasonal level. Many resident species have disappeared from the site. These include Diamond Firetail, Zebra Finch, Hooded Robin, Red-capped Robin, Scarlet Robin, Flame Robin and Black-eared Cuckoo. Other species have declined markedly (Speckled Warbler, Weebill, Brown Treecreeper, Black-chinned Honeyeater, Jacky Winter and Fuscous Honeyeater) while some species have increased in numbers (Brown Thornbill, Superb Fairy- wren and Red-browed Finch). New additions to the community include Spotted Turtle-Dove, Red- whiskered Bulbul, Common Blackbird, Common Myna, Common Starling and House Sparrow, but these have not as yet made an observable impact on the proportions of native species within the community. Seasonal fluctuations in the community are quite marked with up to 34 non-resident species visiting the site with the Rose Robin being the only exclusively winter visitor. The only recorded movement greater than 2 km from the site, was that of a Sacred Kingfisher that travelled to central eastern Queensland. Interaction between the Brown and White-throated Treecreepers as well as the three species of finch (Red-browed Finch, Diamond Firetail and Double-barred Finch) is examined in light of their proportional representation of the resident community. -

Colour Vision and Background Adaptation in a Passerine Bird, the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia Guttata)

Colour vision and background adaptation in a passerine bird, the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Lind, Olle Published in: Royal Society Open Science DOI: 10.1098/rsos.160383 2016 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Lind, O. (2016). Colour vision and background adaptation in a passerine bird, the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Royal Society Open Science, 3(9), [160383]. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160383 Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Downloaded from http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on September 14, 2016 Colour vision and background adaptation in a rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org passerine bird, the zebra Research finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Cite this article: Lind O. -

NSW Native Animal Keepers' Species List 2014

NSW Native Animal Keepers’ Species List 2014 The NSW Native Animal Keepers’ Species List 2014 (also available at www.environment.nsw.gov.au) contains the names of all species that may be kept under licence. If the animal species you want to keep isn’t listed, you generally cannot keep it, although the Department might consider requests to keep unlisted species of reptile, bird or amphibian. If you are applying for a licence for an unlisted species, you will need to supply details of the species and numbers you are proposing to keep, the legal availability of the species and its husbandry requirements in captivity. A new species list is produced by the Department each year. You can only hold an animal that is applicable to class as listed in the current year’s species list. Some animals are listed as exempt and a licence is not required to hold or trade those species (see exempt species list at the back of this document). Some hybridised animals are recorded in this list. The Department does not support native animal keepers who breed between animals of different species. Regulations prohibit the breeding of native waterfowl with domestic waterfowl. Your licence must be endorsed with the class under which the species is applicable. Holding requirements for venomous reptiles must be in accordance with the requirements contained in the class criteria for advanced reptile venomous category 1,2 or 3 as contained in the “Application for an Advanced Class- Native Animal Keepers’ Licence.” If you acquire or dispose of a native species of Cockatoo listed as applicable to class B1, or any species of animal listed under A2,B2,B3,R2,R3,R4 or R5 you must notify the Director General by email or in writing of the details of the transaction within fourteen days of the transaction taking place. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

Native Animal Species List

Native animal species list Native animals in South Australia are categorised into one of four groups: • Unprotected • Exempt • Basic • Specialist. To find out the category your animal is in, please check the list below. However, Specialist animals are not listed. There are thousands of them, so we don’t carry a list. A Specialist animal is simply any native animal not listed in this document. Mammals Common name Zoological name Species code Category Dunnart Fat-tailed dunnart Sminthopsis crassicaudata A01072 Basic Dingo Wild dog Canis familiaris Not applicable Unprotected Gliders Squirrel glider Petaurus norfolcensis E04226 Basic Sugar glider Petaurus breviceps E01138 Basic Possum Common brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula K01113 Basic Potoroo and bettongs Brush-tailed bettong (Woylie) Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi M21002 Basic Long-nosed potoroo Potorous tridactylus Z01175 Basic Rufous bettong Aepyprymnus rufescens W01187 Basic Rodents Mitchell's hopping-mouse Notomys mitchellii Y01480 Basic Plains mouse (Rat) Pseudomys australis S01469 Basic Spinifex hopping-mouse Notomys alexis K01481 Exempt Wallabies Parma wallaby Macropus parma K01245 Basic Red-necked pademelon Thylogale thetis Y01236 Basic Red-necked wallaby Macropus rufogriseus K01261 Basic Swamp wallaby Wallabia bicolor E01242 Basic Tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii eugenii C05889 Basic Tasmanian pademelon Thylogale billardierii G01235 Basic 1 Amphibians Common name Zoological name Species code Category Southern bell frog Litoria raniformis G03207 Basic Smooth frog Geocrinia laevis -

The Differential Effects of Stress on the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia Guttata) Brain and Behavior

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Neuroscience Institute Dissertations Neuroscience Institute 8-7-2018 The Differential Effects of Stress on the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Brain and Behavior Shauna C. Cheesman Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/neurosci_diss Recommended Citation Cheesman, Shauna C., "The Differential Effects of Stress on the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Brain and Behavior." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/neurosci_diss/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Neuroscience Institute at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Neuroscience Institute Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS OF STRESS ON THE ZEBRA FINCH (TAENIOPYGIA GUTTATA) BRAIN AND BEHAVIOR by SHAUNA CHIVON CHEESMAN Under the Direction of Laura L. Carruth, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The detrimental effects of early life stress on brain development and behavior in adulthood are well known, but the effects of acute stressors experienced later in life on brain activation and adult behaviors, such as mate preference, are less understood. It is generally thought that acute stress, unlike chronic stress, leads to adaptive responses like encouraging reproduction over survival. The reverse, promoting survival over reproduction, occurs under chronic stress conditions. Physiological responses to stress are mediated by glucocorticoids receptors (GRs) and DNA methylation has been proposed as a mechanism by which stress, at any point in life, can lead to adaptive and maladaptive changes in the brain and in behavior. -

Aboriginal Bird Names- South Australia

October, 1955 THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 91 ABORIGINAL BIRD NAMES - SOUTH AUSTRALIA Part Two By H. T. CONDON, S.A. Museum WELCOME SWALLOW thindriethindrie, Dieri (Gason) Hirundo neoxena titjeritjera, Aranda (C. Strehlow) . ioisjililki, Ngadj uri (Berndt & Vogels.) duioara, Narangga (Tindale) yerrellyerra, Aranda (Willshire) Ooon-gilga, "Central Australia" (Bates) Most of these names are onomatopaeic. koolgeelga, Kokata (Sullivan) menmenengkuri, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) RESTLESS FLYCATCHER mulya mulyayapunie, Dieri (Cason) warrakka, Pangkala (Schurmann) Seisura inquieta worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) didideilja (or) ditidilja, Narangga (Tindale) The following -names probably refer to this djirba, Wirangu (Bates) species: khinter-khinter, Kokata/Wirangu (Sullivan) mannmanninya, Kaurna (Teich. & Schur.) miduga, Narangga (Howitt) SCARLET ROBIN Petroica multicolor WHITE·BACKED SWALLOW jupi, Ngadjuri (Berndt & Vogels.) Cheramoeca leucosterna tat-kana, Buanditj (Campbell et alia) kaldaldake, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) turon go, Warki (Moorhouse) worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) tuta, "Encounter Bay" (Wyatt) tuttaipitti, Kaurna (Teich. & Schur.) TREE MARTIN Hylochelidon nigricans RED·CAPPED ROBIN wireldutulduti, Wailpi (Hale & Tindale) Petroica goodenovii worraga, KokatajWirangu (Sullivan) choonda, Dieri (Gason) yukourolconi, Wailpi (Hale & Tindale) eeningee-lab-lab, Aranda '(Chewings) eeninjeelabbab (Willshire) MARTIN kummeracheeta, Wirangu (Sullivan) . Hylochelidon sp, -literally 'uncle bird' menmeneng-kuri, 'Narrinyeri' (Taplin) .malitelita, Wailpi -

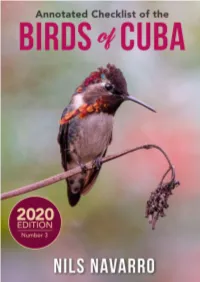

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Drinking Mechanisms in the Zebra Finch and the Bengalese Finch’

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY I_\! Volume 92 Number 1 February 1990 MAROh WI0 The Condor 92: 1-28 Q The Cooper Ornithological Society 1990 WVERSITY OF ~[4br-fJ- DRINKING MECHANISMS IN THE ZEBRA FINCH AND THE BENGALESE FINCH’ J. HEIDWEILLER AND G. A. ZWEERS~ Department of NeurobehavioralMorphology, Zoological Laboratory, Universityof Leiden, The Netherlands Abstract. Two kinds of drinking behavior were studied by film and radiogram analysis of tip down drinking Zebra Finches (Poephilaguttata) and tip up drinking BengaleseFinches (Lonchurastriata) which use similar scoopingtongue motions to carry water into the mouth. Water transport through the pharynx differs: the Zebra Finch usesa scoopingmotion of the larynx that reoccurs in every motion cycle, while the beak is kept down. The Bengalese Finch elevates the head allowing water to flow downward due to gravity and pharyngeal properistalsis.Extensive analysesshow the anatomy of the speciesto be highly similar. The Zebra Finch is able to drink by a double scoop mechanism, because-unlike the Bengalese Finch-reflexes for glottis closure and esophagealperistalsis are used. Integration of these reflexesand a shift in timing of the larynx-scoophas modified tip up into tip down drinking. Thus, tip down is more complex than tip up drinking, since here actions from different cyclesand patterns are integrated in one motion cycle. Increased kinematic complexity is, apart from any historical scenario,an argumentthat tip down is derived from tip up drinking in Estrildidae. An evolutionary scenario is presented in which developments of scooping anatomical elements are seen as preadaptations.These developed by selectionon elements serving the highly specialized kind of feeding on seedsof Gramineae under high predator pressurein open fields, and allowed a wide secondaryextension of the feeding area.