Income Trusts: a Challenge for Regulators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc

February 22, 2019 Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc. SIMPLIFIED PROSPECTUS Offering Series A, Series AT5, Series T5, Series T8, Series D, Series F, Series F5, Series F8, Series FT5, Series I and Series O securities as indicated. Sun Life Granite Conservative Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Moderate Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Balanced Portfolio (Series A, T5, D, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Balanced Growth Portfolio (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Growth Portfolio (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Income Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Enhanced Income Portfolio (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Sentry Value Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Infrastructure Fund† (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Schroder Global Mid Cap Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic American Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Templeton Global Bond Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic Equity Income Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic Strategic Yield Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life NWQ Flexible Income Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life BlackRock Canadian Equity Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I and O securities) Sun Life BlackRock Canadian Balanced Fund (Series A, T5, F, F5, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Canadian Bond Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Canadian Equity Growth Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Dividend Income Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS U.S. -

Franklin Limited Duration Income Trust Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT FRANKLIN LIMITED DURATION INCOME TRUST December 31, 2020 Contents Annual Report Franklin Limited Duration Income Trust ���������������������������������2 Performance Summary����������������������������������������������������������5 Financial Highlights and Statement of Investments���������������7 Financial Statements �����������������������������������������������������������29 Notes to Financial Statements���������������������������������������������33 Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm ��������������������������������������������������������45 Tax Information ��������������������������������������������������������������������46 Important Information to Shareholders ��������������������������������47 Annual Meeting of Shareholders �����������������������������������������54 Dividend Reinvestment and Cash Purchase Plan ���������������55 Board Members and Officers�����������������������������������������������57 Shareholder Information ������������������������������������������������������62 Visit franklintempleton.com/investor/ investments-and-solutions/investment- options/closed-end-funds/ for fund updates, to access your account, or to find helpful financial planning tools. Not FDIC Insured May Lose Value No Bank Guarantee franklintempleton.com Annual Report 1 ANNUAL REPORT Franklin Limited Duration Income Trust Dear Shareholder: Economic and Market Overview This annual report for Franklin Limited Duration Income Trust Financial markets ended 2019 amid an accommodative U�S� covers the fiscal year -

2020 Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) and Widely Held Fixed Investment Trust (WHFIT) Guide

Disclosure 2020 Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) and Widely Held Fixed Investment Trust (WHFIT) Guide Investor’s guide to tax reporting for REMIC/WHFIT regular interests and other CDOs Highlights − This guide helps you understand the tax reporting information related to investments in a collateralized debt obligation (CDO), a debt instrument that is secured by a pool of other debt instruments. − CDOs that are secured by mortgage obligations take the form of a regular interest in a real estate mortgage investment conduit (REMIC). − Widely held fixed investment trusts (WHFITs) whose assets are mortgages, amounts received on mortgages and reasonably required reserve funds as measured by value are considered widely held mortgage trusts (WHMTs). − Taxable interest is calculated using the accrual method of accounting; therefore, the amount reported on Form 1099-INT may not equal the sum of cash payments you actually received during the year. − Original issue discount (OID) and interest accrual amounts for a REMIC regular interest or CDO are already calculated by the issuer or issuer’s agent and provided on your Consolidated Form 1099. − You may be required to use a portion of the acquisition premium to reduce OID included in income during the current year, but only with respect to the same REMIC regular interest or CDO. − If you bought your REMIC regular interest or CDO in the secondary market, you may be required to report market discount income. − If a debt instrument issued with OID was purchased with bond premium, you may eliminate the OID included in current taxable income. − The sale of a REMIC regular interest or CDO that has OID or market discount is subject to special treatment, which may decrease any capital gain or increase any capital loss. -

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (Gifs)

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (GIFs) ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SUN LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY OF CANADA December 31, 2015 Life’s brighter under the sun Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada is a member of the Sun Life Financial group of companies. © Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 2016. 36D-0092-02-16 Table of Contents Independent Auditors' Report 3 Sun MFS Dividend Income 196 Sun Beutel Goodman Canadian Bond 5 Sun MFS Global Growth 200 Sun BlackRock Canadian Balanced 10 Sun MFS Global Total Return 204 Sun BlackRock Canadian Composite Equity 15 Sun MFS Global Value 209 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity 20 Sun MFS Global Value Bundle 214 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity Bundle 25 Sun MFS International Growth 218 Sun BlackRock Cdn Composite Eq Bundle 29 Sun MFS International Growth Bundle 222 Sun BlackRock Cdn Universe Bond 33 Sun MFS International Value 226 Sun Canadian Balanced Bundle 38 Sun MFS International Value Bundle 230 Sun CI Cambridge Canadian Equity 42 Sun MFS Monthly Income 234 Sun CI Cambridge Cdn Asset Allocation 46 Sun MFS US Equity 238 Sun CI Cambridge Global Equity 50 Sun MFS US Equity Bundle 242 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Canadian Bundle 54 Sun MFS US Growth 246 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Global Bundle 58 Sun MFS US Value 250 Sun CI Signature Diversified Yield II 62 Sun MFS US Value Bundle 255 Sun CI Signature High Income 66 Sun Money Market 259 Sun CI Signature Income & Growth 70 Sun NWQ Flexible Income 264 Sun Daily Interest 74 Sun PH&N Short Term Bond and Mortgage 268 Sun Dollar Cost Average Daily Interest 78 Sun RBC Global High -

Instructions for Completing the Investment Information Summary (Form 8)

Financial Services 5160 Yonge Street Commission Box 85 of Ontario Toronto ON M2N 6L9 Instructions for Completing the Investment Information Summary (Form 8) General Information Who Must File Where a pension plan registered with the Financial Services Commission of Ontario (FSCO) provides defined benefits, the plan administrator must file an Investment Information Summary (IIS) each year concurrently with the financial statements for the pension plan filed with FSCO. Where to Obtain the IIS Form The blank IIS form is available from the FSCO website at www.fsco.gov.on.ca, by clicking the “Forms” link at the top of the main page and then selecting “Pension Forms”. Relevant Statutes and Regulations The following statutes and their related regulations are referred to in the IIS and these instructions: • the Ontario Pension Benefits Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.8, as amended (the PBA) − Regulation 909, R.R.O. 1990, as amended (the Regulation 909) • the federal Pension Benefits Standards Act, 1985, R.S.C. 1985, c. 32 (2nd supp.), as amended (the PBSA) − the Pension Benefits Standards Regulations, 1985, SOR/87-19, as amended (the Pension Benefits Standards Regulations, 1985) • the federal Income Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 1 (5th supp.), as amended (the ITA) − the Income Tax Regulations, C.R.C., c. 945, as amended (the Income Tax Regulations) These statutes and regulations can be found on the internet either at http://www.canlii.org or at http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca and http://laws.justice.gc.ca. Hybrid DB/DC Plans Where a pension plan contains both a defined benefit (DB) component and a defined contribution (DC) component, the IIS should contain the information for the DB component only. -

Reserve Royalty Income Trust

January 2021 RESERVE ROYALTY SUMMARY Pure Play Royalty: Quality long duration assets High margins at zero cost with multi-year upside Sustainable production through third party drilling Royalty interests have no capital commitments, at no cost to Reserve Royalty. operating costs, abandonment obligation or 2019: 12 wells drilled reclamation charges associated with working 2020: 12 wells drilled interest ownership assets. 2021E: 19 wells drilled* Returns to Unitholders & Clean Balance Sheet Global Alignment Sustainable target of funds flow paid to unitholders Debt free with positive working capital and an of 60 – 70%. undrawn credit facility ($8 million). No capital Management and Directors own 13.9% of the commitments or operating cash costs. outstanding 107.1 Million trust units to ensure alignment with unit holders. * As evaluated by third party engineers CORPORATE PROFILE 2021E Royalty Revenue • ~$4.0 million Annual Dividend (1) • $0.02 / unit Reserve Value (2) • $31.7 million Net Asset Value (2) • $0.31 / unit Net Debt Outstanding • Nil (1) Dividend subject to realized commodity prices and board approval (2) Based on estimated Total Proved reserves at Gilbert, Launsten & Jung (GLJ) price forecasts. LEADERSHIP TEAM Management Team Board of Directors Rick F. (Buck) Braund, CEO & Chairman (1) (3) Rick F. (Buck) Braund, CEO & Chairman Previously, Co-Founder and Chairman of Peyto Exploration Extensive strategic experience in the oil and gas industry as Michael Culbert (1) (2) (3) a director of Peyto Exploration, Gear Energy Corporation Former President and CEO of Petronas Energy Canada Ltd. formerly Progress Energy and Petrus Resources. Canada Ltd. and appointed Vice Chairman on the Board of Directors. -

Permanent University Fund Detail Schedules of Investment Securities and Independent Auditors’ Report

PERMANENT UNIVERSITY FUND DETAIL SCHEDULES OF INVESTMENT SECURITIES AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT August 31, 2014 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT ON SUPPLEMENTAL SCHEDULES The Board of Regents of The University of Texas System The Board of Directors of The University of Texas Investment Management Company We have audited the financial statements of the Permanent University Fund (the “PUF”) as of and for the years ended August 31, 2014 and 2013, and have issued our report thereon dated October 31, 2014, which contained an unmodified opinion on those financial statements. Our audits were conducted for the purpose of forming an opinion on the financial statements as a whole. The supplemental schedules consisting of the PUF’s equity securities (Schedule A), preferred stocks (Schedule B), purchased options (Schedule C), debt securities (Schedule D), investment funds (Schedule E), physical commodities (Schedule F), cash and cash equivalents (Schedule G), hedge fund investment funds (Schedule H), and private investment funds (Schedule I) as of August 31, 2014 are presented for the purposes of additional analysis and are not a required part of the financial statements. These schedules are the responsibility of The University of Texas Investment Management Company and were derived from and relate directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements. Such schedules have been subjected to the auditing procedures applied in our audits of the financial statements and certain additional procedures, including comparing and reconciling such information directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements or to the financial statements themselves, and other additional procedures in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

The Secret Life of the Trust: the Trust As an Instrument of Commerce

Essay The Secret Life of the Trust: The Trust as an Instrument of Commerce John H. Langbein' In the culture of Anglo-American law, we think of the trust as a branch of the law of gratuitous transfers. That is where we teach trusts in the law school curriculum,' that is where we locate trusts in the statute books,- and that is where American lawyers typically encounter the trust in their practice. The trust originated at the end of the Middle Ages as a means of transferring wealth within the family,' and the trust remains our characteristic device for organizing intergenerational wealth transmission when the transferor has substantial assets or complex family affairs. In the succinct formulation of Bernard Rudden, Anglo-American lawyers regard the trust as "essentially a gift, projected on the plane of time and so subjected to a management regime."4 t Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University I acknowledge with gratitude the able research assistance of Marie DeFalco. I have discussed the subject of this Essay in lectures at the University of Tennessee College of Law (Knoxville, September 1996) and at the Trust Companies Association of Japan (Tokyo, October 1996). 1 am grateful for references and suggestions from those learned audiences and from Anne Alstot. Mark Ascher. Ian Ayres. Robert Ellickson. Tamar Frankel. Henry Hansmann, John Harvey. Howell E. Jackson, Kent H. McMahan, Thomas E Plank. Robcrta Romano. Steven A. Sass, Steven L. Schwarcz. John Simon, Gregory M Stein. Liwrence W Waggoner. and Robert J.Zutz. Many trust and investment industry professionals have helped me to learn about commercial practice, and some are acknowledged in the notes. -

PAAC E-News, February • 2006

Public Affairs: Your Online Newsletter February • 2006 Public Affairs: Your Online Newsletter February • 2006 • President's Message: I am woman; hear me more • Conference 2006: Accountability in public service • Event report: Darrell Bricker and the poisoned chalice • The Book Man: A high probability of enlightenment • The web editor: All the dirt on the Kyoto protocol President's message I am woman; hear me more by Elaine Flis PAAC President In the recent general election, as in elections past, advocates for women in politics talked a great deal about the scarcity of women candidates. And once again the focus was on the need to increase the number of candidates running for political parties by breaking down barriers to their participation. Yet we rarely look beyond that, to assess what happens to recruit, motivate and engage women in the political process between elections. Like now. If democracy is to be truly representative, women must be at the decision-making table, and in significant roles rather than minor ones. But before that can happen at the government level it must happen in the political parties themselves. A look at party leaders' offices across the country shows a depressing lack of top-level involvement by women. Most female political staff are in supporting roles or are, at best, in middle management positions. An embarrassingly small number are appointed chief of staff to a leader or welcomed into the leader's inner circle. Now, with our new Prime Minister's cabinet unveiled, that lack is once again seen at the top. Why is lack of women at the top bad for the country? Because it means less innovation in thinking. -

Summary Prospectus| March 2, 2020

DCM/INNOVA HIGH DIVIDEND INCOME INNOVATION FUND TICKER SYMBOL: TILDX Summary Prospectus | March 2, 2020 Before you invest, you may want to review the Fund’s Prospectus and 1 “Total Annual Fund Operating Expenses” and “Total Annual Statement of Additional Information, which contain more information Fund Operating Expenses After Fee Reductions and/or Expense about the Fund and its risks. You can find the Fund’s Prospectus, Reimbursements” will not correlate to the ratios of expenses to Statement of Additional Information and other information about the the average net assets in the DCM/INNOVA Fund’s Financial Fund online at http://www.DCMmutualfunds.com. You can also get Highlights, which reflect the operating expenses of the DCM/ INNOVA Fund and do not include “Acquired Fund Fees and this information at no cost by calling 1-888-484-5766 or by sending an Expenses.” e-mail request to [email protected]. The Fund’s 2 DCM Advisors, LLC (the “Advisor”) entered into an Expense Prospectus and Statement of Additional Information, dated March 2, Limitation Agreement with the DCM/INNOVA Fund under which 2020, are incorporated by reference into this Summary Prospectus. it has contractually agreed to reduce the amount of the investment advisory fees to be paid to the Advisor by the DCM/INNOVA Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted Fund and to assume other expenses of the DCM/INNOVA Fund, by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of the if necessary, in an amount that limits the DCM/INNOVA Fund’s Fund’s shareholder reports will no longer be sent by mail, unless annual operating expenses (exclusive of interest, taxes, brokerage you specifically request paper copies of the reports from the Fund commissions, other expenditures which are capitalized in or from your financial intermediary such as a broker-dealer or bank. -

Word Template for Creating Internal Use Only Pdfs in Portrait Mode

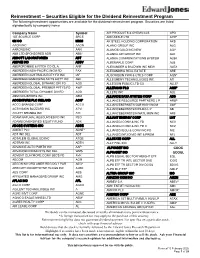

Reinvestment – Securities Eligible for the Dividend Reinvestment Program The following investment opportunities are available for the dividend reinvestment program. Securities are listed alphabetically by company name Company Name Symbol AIR PRODUCTS & CHEMICALS APD 1ST SOURCE CORP SRCE AIRCASTLE LTD AYR* 3M CO MMM AK STEEL HOLDING CORPORATION AKS AAON INC AAON ALAMO GROUP INC ALG AARONS INC AAN ALAMOS GOLD INC NEW AGI* ABB LTD SPONSORED ADR ABB* ALASKA AIR GROUP INC ALK ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABT ALASKA COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEM ALSK ABBVIE INC ABBV ALBEMARLE CORP ALB ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO CL A ANF ALEXANDER & BALDWIN INC NEW ALEX ABERDEEN ASIA-PACIFIC INCM FD FAX ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE ARE ABERDEEN AUSTRALIA EQTY FD INC IAF ALGONQUIN PWR & UTILS CORP AQN* ABERDEEN EMERGING MKTS EQTY INC AEF ALLEGHENY TECHNOLOGIES INC ATI ABERDEEN GLOBAL DYNAMIC DIV FD AGD ALLEGION PUBLIC LTD CO ALLE* ABERDEEN GLOBAL PREMIER PPTYS FD AWP ALLERGAN PLC AGN* ABERDEEN TOTAL DYNAMIC DIV FD AOD ALLETE INC ALE ABM INDUSTRIES INC ABM ALLIANCE DATA SYSTEM CORP ADS ACCENTURE PLC IRELAND ACN* ALLIANCE RESOURCE PARTNERS L P ARLP ACCO BRANDS CORP ACCO ALLIANCEBERNSTN GLB HIGH INCM AWF ACTIVISION BLIZZARD INC ATVI ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN HLDG L P AB ACUITY BRANDS INC AYI ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN NATL MUN INC AFB ADAM NATURAL RESOURCES FD INC PEO ALLIANT ENERGY CORP LNT ADAMS DIVERSIFIED EQUITY FUND ADX ALLIANZGI CONV & INC FD NCV ADOBE SYSTEMS INC ADBE ALLIANZGI CONV & INC FD II NCZ ADIENT PLC ADNT* ALLIANZGI EQU & CONV INC FD NIE ADT INC DEL ADT ALLIANZGI NFJ DIVID INT & PREM NFJ ADTALEM -

Client Guide to 2019 Tax Reporting

HNW_NRG_C_Bleed_Transp Client guide to 2019 tax reporting This guide summarizes the important dates and required tax information to prepare your annual tax return. It also includes a handy list of potential tax slips you may receive from The Royal Trust Company and Royal Trust Corporation of Canada (Royal Trust) depending on your investment Please contact holdings and account activity. us if you have any questions about your tax package. Important dates T5 tax package – March 02, 2020 – last day for outstanding tax documents 2019 RRSP contributions. We issue several tax slips and April 30, 2020 – last day to file your supporting documents to assist you 2019 tax return without penalty. in preparing your tax return. It is important to ensure that you have all June 15, 2020 – last day to file your of your slips before you file your tax 2019 tax return without penalty if return. Please review the two handy you are self-employed. checklists within the cover letter of your T5 tax package: “Outstanding Access your tax slips online tax documents you may receive To help make tax time easier for from our firm” and “Outstanding tax you, your 2019 tax slips are available documents you may receive from electronically via WM Online. third parties.” This year, even more tax slips will be available online, including Multiple account holders/estates mutual fund tax slips issued by Joint accounts: Although tax slips for ® RBC (tax slips issued by other joint accounts are issued in the name issuers outside of RBC will continue of two (or more) individuals, Canada to be sent by regular mail).