The Secret Life of the Trust: the Trust As an Instrument of Commerce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc

February 22, 2019 Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc. SIMPLIFIED PROSPECTUS Offering Series A, Series AT5, Series T5, Series T8, Series D, Series F, Series F5, Series F8, Series FT5, Series I and Series O securities as indicated. Sun Life Granite Conservative Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Moderate Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Balanced Portfolio (Series A, T5, D, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Balanced Growth Portfolio (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Growth Portfolio (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Income Portfolio (Series A, T5, F, F5, I, O securities) Sun Life Granite Enhanced Income Portfolio (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Sentry Value Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Infrastructure Fund† (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Schroder Global Mid Cap Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic American Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I, O securities) Sun Life Templeton Global Bond Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic Equity Income Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life Dynamic Strategic Yield Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life NWQ Flexible Income Fund (Series A, F, I, O securities) Sun Life BlackRock Canadian Equity Fund (Series A, T5, T8, F, F5, F8, I and O securities) Sun Life BlackRock Canadian Balanced Fund (Series A, T5, F, F5, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Canadian Bond Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Canadian Equity Growth Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS Dividend Income Fund (Series A, D, F, I and O securities) Sun Life MFS U.S. -

2020 Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) and Widely Held Fixed Investment Trust (WHFIT) Guide

Disclosure 2020 Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) and Widely Held Fixed Investment Trust (WHFIT) Guide Investor’s guide to tax reporting for REMIC/WHFIT regular interests and other CDOs Highlights − This guide helps you understand the tax reporting information related to investments in a collateralized debt obligation (CDO), a debt instrument that is secured by a pool of other debt instruments. − CDOs that are secured by mortgage obligations take the form of a regular interest in a real estate mortgage investment conduit (REMIC). − Widely held fixed investment trusts (WHFITs) whose assets are mortgages, amounts received on mortgages and reasonably required reserve funds as measured by value are considered widely held mortgage trusts (WHMTs). − Taxable interest is calculated using the accrual method of accounting; therefore, the amount reported on Form 1099-INT may not equal the sum of cash payments you actually received during the year. − Original issue discount (OID) and interest accrual amounts for a REMIC regular interest or CDO are already calculated by the issuer or issuer’s agent and provided on your Consolidated Form 1099. − You may be required to use a portion of the acquisition premium to reduce OID included in income during the current year, but only with respect to the same REMIC regular interest or CDO. − If you bought your REMIC regular interest or CDO in the secondary market, you may be required to report market discount income. − If a debt instrument issued with OID was purchased with bond premium, you may eliminate the OID included in current taxable income. − The sale of a REMIC regular interest or CDO that has OID or market discount is subject to special treatment, which may decrease any capital gain or increase any capital loss. -

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (Gifs)

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (GIFs) ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SUN LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY OF CANADA December 31, 2015 Life’s brighter under the sun Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada is a member of the Sun Life Financial group of companies. © Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 2016. 36D-0092-02-16 Table of Contents Independent Auditors' Report 3 Sun MFS Dividend Income 196 Sun Beutel Goodman Canadian Bond 5 Sun MFS Global Growth 200 Sun BlackRock Canadian Balanced 10 Sun MFS Global Total Return 204 Sun BlackRock Canadian Composite Equity 15 Sun MFS Global Value 209 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity 20 Sun MFS Global Value Bundle 214 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity Bundle 25 Sun MFS International Growth 218 Sun BlackRock Cdn Composite Eq Bundle 29 Sun MFS International Growth Bundle 222 Sun BlackRock Cdn Universe Bond 33 Sun MFS International Value 226 Sun Canadian Balanced Bundle 38 Sun MFS International Value Bundle 230 Sun CI Cambridge Canadian Equity 42 Sun MFS Monthly Income 234 Sun CI Cambridge Cdn Asset Allocation 46 Sun MFS US Equity 238 Sun CI Cambridge Global Equity 50 Sun MFS US Equity Bundle 242 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Canadian Bundle 54 Sun MFS US Growth 246 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Global Bundle 58 Sun MFS US Value 250 Sun CI Signature Diversified Yield II 62 Sun MFS US Value Bundle 255 Sun CI Signature High Income 66 Sun Money Market 259 Sun CI Signature Income & Growth 70 Sun NWQ Flexible Income 264 Sun Daily Interest 74 Sun PH&N Short Term Bond and Mortgage 268 Sun Dollar Cost Average Daily Interest 78 Sun RBC Global High -

Instructions for Completing the Investment Information Summary (Form 8)

Financial Services 5160 Yonge Street Commission Box 85 of Ontario Toronto ON M2N 6L9 Instructions for Completing the Investment Information Summary (Form 8) General Information Who Must File Where a pension plan registered with the Financial Services Commission of Ontario (FSCO) provides defined benefits, the plan administrator must file an Investment Information Summary (IIS) each year concurrently with the financial statements for the pension plan filed with FSCO. Where to Obtain the IIS Form The blank IIS form is available from the FSCO website at www.fsco.gov.on.ca, by clicking the “Forms” link at the top of the main page and then selecting “Pension Forms”. Relevant Statutes and Regulations The following statutes and their related regulations are referred to in the IIS and these instructions: • the Ontario Pension Benefits Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.8, as amended (the PBA) − Regulation 909, R.R.O. 1990, as amended (the Regulation 909) • the federal Pension Benefits Standards Act, 1985, R.S.C. 1985, c. 32 (2nd supp.), as amended (the PBSA) − the Pension Benefits Standards Regulations, 1985, SOR/87-19, as amended (the Pension Benefits Standards Regulations, 1985) • the federal Income Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 1 (5th supp.), as amended (the ITA) − the Income Tax Regulations, C.R.C., c. 945, as amended (the Income Tax Regulations) These statutes and regulations can be found on the internet either at http://www.canlii.org or at http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca and http://laws.justice.gc.ca. Hybrid DB/DC Plans Where a pension plan contains both a defined benefit (DB) component and a defined contribution (DC) component, the IIS should contain the information for the DB component only. -

Permanent University Fund Detail Schedules of Investment Securities and Independent Auditors’ Report

PERMANENT UNIVERSITY FUND DETAIL SCHEDULES OF INVESTMENT SECURITIES AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT August 31, 2014 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT ON SUPPLEMENTAL SCHEDULES The Board of Regents of The University of Texas System The Board of Directors of The University of Texas Investment Management Company We have audited the financial statements of the Permanent University Fund (the “PUF”) as of and for the years ended August 31, 2014 and 2013, and have issued our report thereon dated October 31, 2014, which contained an unmodified opinion on those financial statements. Our audits were conducted for the purpose of forming an opinion on the financial statements as a whole. The supplemental schedules consisting of the PUF’s equity securities (Schedule A), preferred stocks (Schedule B), purchased options (Schedule C), debt securities (Schedule D), investment funds (Schedule E), physical commodities (Schedule F), cash and cash equivalents (Schedule G), hedge fund investment funds (Schedule H), and private investment funds (Schedule I) as of August 31, 2014 are presented for the purposes of additional analysis and are not a required part of the financial statements. These schedules are the responsibility of The University of Texas Investment Management Company and were derived from and relate directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements. Such schedules have been subjected to the auditing procedures applied in our audits of the financial statements and certain additional procedures, including comparing and reconciling such information directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements or to the financial statements themselves, and other additional procedures in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

Summary Prospectus| March 2, 2020

DCM/INNOVA HIGH DIVIDEND INCOME INNOVATION FUND TICKER SYMBOL: TILDX Summary Prospectus | March 2, 2020 Before you invest, you may want to review the Fund’s Prospectus and 1 “Total Annual Fund Operating Expenses” and “Total Annual Statement of Additional Information, which contain more information Fund Operating Expenses After Fee Reductions and/or Expense about the Fund and its risks. You can find the Fund’s Prospectus, Reimbursements” will not correlate to the ratios of expenses to Statement of Additional Information and other information about the the average net assets in the DCM/INNOVA Fund’s Financial Fund online at http://www.DCMmutualfunds.com. You can also get Highlights, which reflect the operating expenses of the DCM/ INNOVA Fund and do not include “Acquired Fund Fees and this information at no cost by calling 1-888-484-5766 or by sending an Expenses.” e-mail request to [email protected]. The Fund’s 2 DCM Advisors, LLC (the “Advisor”) entered into an Expense Prospectus and Statement of Additional Information, dated March 2, Limitation Agreement with the DCM/INNOVA Fund under which 2020, are incorporated by reference into this Summary Prospectus. it has contractually agreed to reduce the amount of the investment advisory fees to be paid to the Advisor by the DCM/INNOVA Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted Fund and to assume other expenses of the DCM/INNOVA Fund, by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of the if necessary, in an amount that limits the DCM/INNOVA Fund’s Fund’s shareholder reports will no longer be sent by mail, unless annual operating expenses (exclusive of interest, taxes, brokerage you specifically request paper copies of the reports from the Fund commissions, other expenditures which are capitalized in or from your financial intermediary such as a broker-dealer or bank. -

Word Template for Creating Internal Use Only Pdfs in Portrait Mode

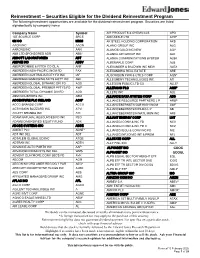

Reinvestment – Securities Eligible for the Dividend Reinvestment Program The following investment opportunities are available for the dividend reinvestment program. Securities are listed alphabetically by company name Company Name Symbol AIR PRODUCTS & CHEMICALS APD 1ST SOURCE CORP SRCE AIRCASTLE LTD AYR* 3M CO MMM AK STEEL HOLDING CORPORATION AKS AAON INC AAON ALAMO GROUP INC ALG AARONS INC AAN ALAMOS GOLD INC NEW AGI* ABB LTD SPONSORED ADR ABB* ALASKA AIR GROUP INC ALK ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABT ALASKA COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEM ALSK ABBVIE INC ABBV ALBEMARLE CORP ALB ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO CL A ANF ALEXANDER & BALDWIN INC NEW ALEX ABERDEEN ASIA-PACIFIC INCM FD FAX ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE ARE ABERDEEN AUSTRALIA EQTY FD INC IAF ALGONQUIN PWR & UTILS CORP AQN* ABERDEEN EMERGING MKTS EQTY INC AEF ALLEGHENY TECHNOLOGIES INC ATI ABERDEEN GLOBAL DYNAMIC DIV FD AGD ALLEGION PUBLIC LTD CO ALLE* ABERDEEN GLOBAL PREMIER PPTYS FD AWP ALLERGAN PLC AGN* ABERDEEN TOTAL DYNAMIC DIV FD AOD ALLETE INC ALE ABM INDUSTRIES INC ABM ALLIANCE DATA SYSTEM CORP ADS ACCENTURE PLC IRELAND ACN* ALLIANCE RESOURCE PARTNERS L P ARLP ACCO BRANDS CORP ACCO ALLIANCEBERNSTN GLB HIGH INCM AWF ACTIVISION BLIZZARD INC ATVI ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN HLDG L P AB ACUITY BRANDS INC AYI ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN NATL MUN INC AFB ADAM NATURAL RESOURCES FD INC PEO ALLIANT ENERGY CORP LNT ADAMS DIVERSIFIED EQUITY FUND ADX ALLIANZGI CONV & INC FD NCV ADOBE SYSTEMS INC ADBE ALLIANZGI CONV & INC FD II NCZ ADIENT PLC ADNT* ALLIANZGI EQU & CONV INC FD NIE ADT INC DEL ADT ALLIANZGI NFJ DIVID INT & PREM NFJ ADTALEM -

SEC Rule 15C2-11Restricted Securities

SEC Rule 15c2-11Restricted Securities On September 28, 2021, new amendments to Rule 15c-211 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 go into effect to enhance investor protection and improve issuer transparency. These amendments restrict the ability of market makers to publish quotations for those companies that have not made required current financial and company information available to regulators and investors. Ahead of the regulatory enforcement date, TD Ameritrade will only accept orders to liquidate positions - (i.e. no new buy orders) starting on or after September 3, 2021. Please note: After the amendment officially goes into effect on September 28, 2021, it may be more difficult to liquidate these securities. Quoting and market liquidity may also be very limited. The list is below as of September 20, 2021 and is subject to change at any time. Symbol Cusip Company Name AACS 025199100 American Commerce Solutions, Inc. AAIIQ 01023E100 Alabama Aircraft Industries, Inc. AASL 03063J205 America's Suppliers, Inc. ABBY 00287T308 Abby, Inc. ABDR 022909204 Ambassador Food Services Corp. ABKB 02451T106 American Basketball Association, Inc. ABPR 00927Q102 Airborne Security & Protective Services, Inc. ABVN 00083Q102 ABV Consulting Inc. ABWN 00928L300 Airborne Wireless Network ACBCQ 013288105 Albina Community Bancorp ACCA 00389L104 Acacia Diversified Holdings, Inc. ACFL 001642107 AMC Financial Holdings, Inc. ACGI 022624100 Amacore Group, Inc. (The) ACLD 004901104 Acquire Ltd. ACNE 016096109 Alice Consolidated Mines, Inc. ACNV 00434W105 Accelera Innovations, Inc. ACRB 04521A109 Asia Carbon Industries, Inc. ACTL 04300F105 Artec Global Media, Inc. ACUS 00511R854 Acusphere, Inc. ADCV 00512R200 AD Capital U.S., Inc. ADDC 006698203 Addmaster Corp. ADFS 025351107 American Defense Systems, Inc. -

Amplify Etf Trust Investment Company Act File No

STATEMENT OF ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AMPLIFY ETF TRUST INVESTMENT COMPANY ACT FILE NO. 811-23108 Amplify High Income ETF YYY Amplify Online Retail ETF IBUY Amplify CWP Enhanced Dividend Income ETF DIVO Amplify Transformational Data Sharing ETF BLOK Amplify Lithium & Battery Technology ETF (formerly Amplify Advanced Battery Metals and Materials ETF) BATT Amplify BlackSwan Growth & Treasury Core ETF SWAN Amplify International Online Retail ETF XBUY Amplify CrowdBureau® Online Lending and Digital Banking ETF (formerly Amplify CrowdBureau® Peer-to-Peer Lending & Crowdfunding ETF) LEND Amplify Seymour Cannabis ETF CNBS DATED MARCH 1, 2021 This Statement of Additional Information (“SAI”) describes shares of each of the funds set forth above (each a “Fund”, and collectively, the “Funds”), each a series of Amplify ETF Trust (the “Trust”). The SAI is not a prospectus and it should be read in conjunction with each Fund’s prospectus, dated March 1, 2021, as may be revised from time to time (each a “Prospectus”). The SAI is incorporated by reference into each Fund’s Prospectus. Capitalized terms used herein that are not defined have the same meanings as in the applicable Prospectus, unless otherwise noted. A copy of each Prospectus may be obtained without charge by writing to the Trust’s distributor, Foreside Fund Services, LLC, Three Canal Plaza, Suite 100, Portland, ME 04101, or by calling toll free at 1-855-267-3837. Each Fund’s shares are principally listed for trading on NYSE Arca, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE TRUST AND THE -

Item 1 – Cover Page

Investment Adviser Brochure Item 1 – Cover Page Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. 200 Crescent Court Suite 1200 Dallas, Texas 75201 (214) 756-6900 www.westwoodgroup.com www.westwoodfunds.com www.westwoodwealthcoach.com August 17, 2021 This brochure provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. If you have any questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at (214) 756-6900 or [email protected]. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or by any state securities authority. Additional information about Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. also is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. is an SEC registered investment adviser. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. Investment Adviser Brochure Item 2 - Material Changes The following material changes have been made to this brochure since the last annual update dated March 31, 2021. Those changes include: Advisory Business: • Updated to include new private investment fund offerings, including those provided through the Blackstone Group. Fees and Compensation: • Updated to include fees and compensation associated with private investment fund offerings. Methods of Analysis, Investment Strategies and Risk of Loss: • Updated to include the objectives and risks related to private investment funds. General Updates: • Updated language throughout the brochure for technical and clarifying purposes. - ii - Westwood Advisors, L.L.C. Investment Adviser Brochure Item 3 - Table of Contents Item 1 – Cover Page ......................................................................................................................... i Item 2 - Material Changes.............................................................................................................. -

A Guide to Your 2018 Consolidated IRS Form1099 Important Information About Tax Reporting for 2018

Disclosure A guide to your 2018 Consolidated IRS Form1099 Important information about tax reporting for 2018 About this guide This comprehensive reference guide is designed to help you in filing your federal income tax return. It provides detailed explanations and examples of the tax reporting statement you may receive, depending on the type of reportable income you have in your account. The Consolidated Form 1099 reflects information that is reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). In most situations, you must report the income shown on Form 1099 when filing your federal income tax return. Please note: – Your Consolidated Form 1099 (rather than your December statement) is the official document for tax reporting purposes. – Various issuers may provide additional information after year-end; therefore, amounts shown on your monthly statement may be different from your Consolidated Form 1099. – Attempting to reconcile the December statement against your Consolidated Form 1099 may be difficult, as the amounts will likely be different. Disclosure This guide is not intended to be used or relied upon for the purposes of tax advice. As tax laws are complex and subject to interpretation, please consult your tax advisor with any tax questions you may have regarding the preparation and filing of your federal income tax return(s). 1 of 39 Table of contents Important dates and deadlines __________________________________________________________________________ 3 What is included on your Consolidated Form 1099 _________________________________________________________ -

Semi-Annual Report

Semi-Annual Report INNOVATOR IBD® 50 ETF (FFTY) INNOVATOR IBD® ETF LEADERS ETF (LDRS) INNOVATOR IBD® BREAKOUT OPPORTUNITIES ETF (BOUT) INNOVATOR LOUP FRONTIER TECH ETF (LOUP) April 30, 2021 Innovator ETFs Trust TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter to Shareholders ......................................................................................... 3 Fund Performance ............................................................................................... 6 Expense Example ................................................................................................. 14 Schedules of Investments ................................................................................... 16 Statements of Assets and Liabilities .................................................................. 28 Statements of Operations ................................................................................... 29 Statements of Changes in Net Assets ................................................................ 30 Financial Highlights ............................................................................................. 32 Notes to Financial Statements ............................................................................ 34 Trustees and Officers .......................................................................................... 50 Additional Information ......................................................................................... 52 INNOVATOR ETFs TRUST Letter to Shareholders (Unaudited) Dear Valued Shareholders, The following