Adivasi Claims Over Sabarimala Highlight the Importance of Counter-Narratives of Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

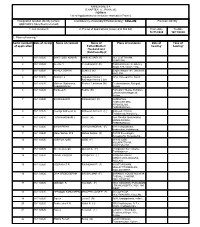

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KOLLAM Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 SANTHOSH KUMAR MANI ACHARI (F) 163, CHITTAYAM, PANAYAM, , 2 16/11/2020 Geethu Y Yesodharan N (F) Padickal Rohini, Residency Nagar 129, Kollam East, , 3 16/11/2020 AKHILA GOPAN SUMA S (M) Sagara Nagar-161, Uliyakovil, KOLLAM, , 4 16/11/2020 Akshay r s Rajeswari Amma L 1655, Kureepuzha, kollam, , Rajeswari Amma L (M) 5 16/11/2020 Mahesh Vijayamma Reshmi S krishnan (W) Devanandanam, Mangad, Gopalakrishnan Kollam, , 6 16/11/2020 Sandeep S Rekha (M) Pothedath Thekke Kettidam, Lekshamana Nagar 29, Kollam, , 7 16/11/2020 SIVADASAN R RAGHAVAN (F) KANDATHIL THIRUVATHIRA, PRAKKULAM, THRIKKARUVA, , 8 16/11/2020 Neeraja Satheesh G Satheesh Kumar K (F) Satheesh Bhavan, Thrikkaruva, Kanjavely, , 9 16/11/2020 LATHIKAKUMARI J SHAJI (H) 184/ THARA BHAVANAM, MANALIKKADA, THRIKKARUVA, , 10 16/11/2020 SHIVA PRIYA JAYACHANDRAN (F) 6/113 valiyazhikam, thekkecheri, thrikkaruva, , 11 16/11/2020 Manu Sankar M S Mohan Sankar (F) 7/2199 Sreerangam, Kureepuzha, Kureepuzha, , 12 16/11/2020 JOSHILA JOSE JOSE (F) 21/832 JOSE VILLAKATTUVIA, -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Environmental Impact of Sand Mining: a Cas the River Catchments of Vembanad La Southwest India

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CAS THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LA SOUTHWEST INDIA Thesis submitted to the COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT UNDER THE FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES BY SREEBHAS (Reg. No. 290 I) CENTRE FOR EARTH SCIENCE STUDIES THlRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695031 DECEMBER 200R Dedicated to my fBe[0 1/ea’ Tatfier Be still like a mountain and flow like a great river. Lao Tse DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled “ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CASE STUDY IN THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LAKE, SOUTHWEST INDIA” is an authentic record of the research work carried out by me under the guidance of Dr. D Padmalal, Scientist, Environmental Sciences Division, Centre for Earth Science Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Management under the faculty of Environmental Studies of the Cochin University of Science and Technology. No part of it has been previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or any other similar title or recognition of this or of any other University. ,4,/~=&P"9 SREEBHA S Thiruvananthapuram November, 2008 CENTRE FOR EARTH SCIENCE STUDIES Kerala State Council for Science, Technology & Environment P.B.No. 7250, Akkulam, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 031 , India CERTIFICATE This is to certify that this thesis entitled "ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF SAND MINING: A CASE STUDY IN THE RIVER CATCHMENTS OF VEMBANAD LAKE, SOUTHWEST INDIA" is an authentic record of the research work carried out by SREEBHA S under my scientific supervision and guidance, in Environmental Sciences Division, Centre for Earth Science Studies. -

Krishna Sukhtas

B¿j ktµiw ARSHA SANDESAM B¿j ktµiw Vol. 19 Issue: 11 November 2019 CONTENTS apJ°pdn∏v .. ..........................................4 {ioaZv`mKhXw ...............................................17 hnhÀ¯\w: Fw. BÀ. BÀ. hmcnbÀ Divinising Emotions ............................5 Swami Tejomayananda abqÀ¡mhne½ ............................................... 19 cma¦ï¯p \µIpamc³ Krishna Sukhtas .......................................7 Adv. P. Ramachandran D]\nj¯ vþefnXhymJym\w .................. 20 F.sI._n. \mbÀ Today is "Chathayam" .............................9 Swami Adhyatmananda Saraswathi `mKhXkmcw ........................................... 23 kzman Atijm\µ t{]amZc in£W Nn´IÄ ................. 10 kzman A²ymßm\µ kckzXn ]qX\mtam£w ......................................... 24 ISembnð `hZmk³ \¼qXncn¸mSv Mandala Pooja Programme .................. 13 t£{X hmÀ¯IÄ ................................. 26 Fsâ taml§Ä ....................................... 16 cmPn Fkv. hmcnbÀ aÞeþaIc hnf¡v BtLmj§Ä aÞe ]qP 17þ11þ2019 apXð 27þ12þ2019 hsc KpcphmbqÀ GImZin aIc hnf¡v A¿¸³ hnf¡v imkvXm{]oXn 8þ12þ2019 15þ1þ2020 23þ11þ2019 14þ12þ2019 Editorial Board V.N.N. Pillai, (Chief Editor) Prof. Omcheri N.N. Pillai, C.M. Nagarajan, M.V. Haridas, G. Balakrishnan Nair, Varathra Sreekumar E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.uttaraguruvayurappan.org Tel: 22710305, 22711029 November 2019 3 B¿j ktµiw apJ¡pdn¸v SCIENCE AND SPIRITUALITY Most often we see debates around Science versus Spirituality. In fact, such debates are mostly based on Western concept of spirituality, where only organized religions are predominant in imbibing spirituality. In ancient India, Science and Spirituality were perfectly in unison so that it was difficult to distinguish a Rishi/Yogi from a Shastrakara/Meemamsaka. Vyasa, Patanjali, Bharatamuni, Kanada, Janaka, Ashtravakra, Sushruta were all Rishis (sages) as well as shastrakaras (experts in various sciences). Mathematics is the base of Science. The fact that India was rich in mathematical knowledge underscores the confluence of mathematical principles and spiritual thoughts. -

Gotmar Festival 105

editorial note INDEPENDENCE DAY AND THE FREEDOM THAT WE LONG FOR Anniversaries are occasions for remembrance and renewal. constructive and inclusive idea of nation yet, social On this note, let us understand the true meaning and empowerment still remains a distant dream for millions. substance in the celebration of Independence Day beyond the glib chest-thumping of social media cheer and the glitz For many Indians, talk of freedom rings hollow: large of orchestrated functions. population is still struggling with deprivation, poverty and discrimination; grim oppression is reserved for those whom According to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar- “By independence, we M.K. Gandhi called God's children; hypocrisy of appeasing have lost the excuse of blaming the British for anything the physically disabled by attributing divinity to their going wrong. If hereafter things go wrong, we will have physique; the original settlers of the subcontinent in their nobody to blame except ourselves. There is great danger of sparse habitations in and around forests, suppressed by things going wrong.” their pretended liberators and extractive industries that covet their land; and people in the disturbed regions where In his last speech in the Constituent Assembly, Dr. democratic processes are getting weakened. Yes, there is Ambedkar had also said, “Castes are anti-national. The much that is less than free and fair in Independent India. sooner we realise that we are not yet a nation in the social and psychological sense of the word, the better for us. For But that is not the point. The point is that we have the then only we shall realise the necessity of becoming a freedom and power to remove the ugliness in our lives, to nation and think of ways and means of realising that goal. -

The Shrine of Lord Ayyappa Or Dharma Sastha on the Sabari Hills on Western Ghats Attracts Lakhs of Devotees

Sabarimala The shrine of Lord Ayyappa or Dharma Sastha on the Sabari hills on Western Ghats attracts lakhs of devotees. According to Puranas, Lord Vishnu once appeared as Mohini and Siva succumbed to Her beauty. Since Ayyappa was born of their union, He is known as Harihara Putra. His other name is Manikantan as he had a golden bell round his neck when he was found by the King of Pandalam on the banks of Pampa. This divine boy is said to have vanquished demoness Mahishi in the Sabari hills. Parasurama had installed five Devi deities along the seashore and five Sastha images along the hilly tracts. Sastha is depicted in different stages of life in these five temples. At Kulathupuzha, He is represented as a child, at Ariyankavu as a Brahmachari, at Achancoil as a Grihastha with His consorts Poorna and Pushkala, at Sabarimala as Vanaprastha and at Ponnambalamedu or Kantamalai, as yogi. Pilgrim season: The main pilgrimage takes place during Vishu (April), Mandala Puja (Dec) and Makara Sankranti (Jan). Pilgrims trekking long distances reach the shrine after negotiating Karimala and Neelimala. Vehicles can go up to the banks of Pampa river. From here it is a five-km trek to reach the hill shrine. The presiding deity is enshrined in a neat little sanctum on a raised ground. Only those who carry Irumudi are allowed to climb the 18 sacred steps leading to the sanctum. Others follow a side entrance. On the evening of Makara Sankranti pilgrims witness a magnificent flash of a light known as Makara Vilakku or Jyothi on the eastern side, called Ponnambalamedu. -

A Study on the Problems and Prospects of Heritage Tourism with Special Reference to Pandalam Palace”

“A STUDY ON THE PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS OF HERITAGE TOURISM WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO PANDALAM PALACE” PROJECT REPORT By Ms. Parvathy R. Nair MCom, PG Dept. of Commerce NSS College Pandalam AUGUST 2016 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 2 INTRODUCTION Tourism is one of the World's largest and fastest growing industries. The world Tourism organizations (WTO) statistics indicate that tourism industry will continue to expand over years. According to WTO, international tourists arrivals worldwide will reach 105 billion by 2020. It was felt that both international and domestic tourism can contribute towards regional development within a country. The most visible economic benefit of tourism is employment. Most sectors of this tourism industry are labour intensive and require relatively short training for most jobs. Employment can be created with relatively low investment in fixed assets per employees. It employs a large number of people and provides a wide range of jobs which extends from unskilled to heavy specialised.WTO has recognised the potential of tourism sector for the purpose of poverty alleviation by increased job creation in the developing countries. In Kerala the total employment generated in the sector both direct and indirect is about seven lakhs. With the accelerated investment in tourism sector there should be direct employment opportunities for over ten thousand persons every year. In India, one state that performed remarkably well in tourism is Kerala. Kerala, 'Gods own country', has emerged as the most acclaimed tourist destinations in the country. During 90's the state achieved growth in tourism than the national average. Tourism industry is one of the few industries in which Kerala has a lot of potential to develop. -

Sabarimala Temple Verdict: a Critical Analysis

1 Sabarimala Temple Verdict: A Critical Analysis Mohit Rana* *LL.B 3rd Semester Department of Laws Panjab University 1. Introduction: The legend of Sabarimala Sri Ayyappan is engraved in the tradition and culture of Malayalee and the powerful God, Sri Ayyappan, also known as Sri Shasthav is profoundly revered as “Brahmachari” by devotees spread all over the south Indian States. Few customs of Sabarimala devotees are fierce. One such custom prohibits the entry of women inside the temple during her menstrual years of life i.e. from 10 to 50 years of age. The ban is due to the belief of devotees who consider Lord Ayyappa, the presiding deity of temple, to be celibate.1 One such custom applicable on male devotees who aspire for a darshan of Lord Ayyapppan has to pure themselves physically and mentally and for this they are required to keep 41 days of “vritham”2 during which male devotees have to refrain themselves from eating non vegetarian food, liquor and from making any contact with women. Further devotees wear black clothes and remain unshaven in order to be identified as devotees of Sri Ayyapan during such 41 days of “vritham” who are commonly called as “KanniAyyapppan.” The sabarimalasannidhanam (temple) is open to devotees only during mandalapooja (November to January), makaravilakku , vishu and the beginning of every month in the malayalam calendar.3 The Ayyappa temple at Sabarimala is one of the few Hindu temples in India that is open to all faiths. Here, the emphasis is on secularism and communal harmony. Sabarimala upholds the values of equality, fraternity and also the oneness of the human soul; all men, irrespective of *Mohit Rana, Student, LL.B 1st Year, Department of Laws, Panjab University Chandigarh. -

Master Plan Module – Landscape Module

Master Plan for Sabarimala Landscape Module MASTER PLAN MODULES LANDSCAPE MODULE 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction and Relevance................................................................................................1 1.2 Aims and Objectives............................................................................................................2 1.3 Methodology.........................................................................................................................2 1.4 Scope of the Study ...............................................................................................................3 1.5 Structure of the Report .......................................................................................................3 2. PLANNING REGION FOR LANDSCAPE MICRO PLAN ...............................................5 2.1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................5 2.2 Planning Region...................................................................................................................5 2.3 Need for Planning Guidelines.............................................................................................6 2.4 Planning Time Frames / Horizon.......................................................................................7 3. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL SCENARIO OF THE HOST REGION..................8 -

Sabarimala Pilgrimage

MANAGING RELIGIOUS CROWD SAFELY CRISIS MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR SABARIMALA PILGRIMAGE PROJECT REPORT Institute of Land and Disaster Management Department of Revenue and Disaster Management Government of Kerala PROJECT TEAM Faisel T Illiyas Assistant Professor & Project In Charge Institute of Land and Disaster Management Government of Kerala & Naveen Babu Project Fellow Sabarimala Crisis Management Project Institute of Land and Disaster Management CONTENTS Preface Sabarimala Pilgrimage Sabarimala Crisis Management Plan I. Purpose II. Definition of “Crisis” III Objectives IV. Authority V Familiarization VI Hazard Analysis Sector I: Sannidanam Sector Ii: Trekking Paths Sector Iii: Pamba VII Crisis Management Plan for Sannidanam VIII. Incident Control and Crisis Communication IX. Evacuation X. Medical Emergencies and Mass Casualty Management Triage Process Emergency Medical Transportation from Sannidanam Arrangements Required at Pamba XI. Disaster Specific Response XII. Documenting a Crisis or Emergency XIII. What Marks the End of a Crisis? ANNEXURE I. Recommendations ANNEXURE II. Makaravilakku disaster preparedness ANNEXURE III: Safety Guideline for Disaster Mitigation ANNEXURE IV: Establishment and Function of Emergency Operation Centre (EOC) ANNEXURE V: Emergency Contact Numbers PREFACE Mass gathering in remote locations under limited infrastructural facilities often pose serious threat to human stampedes and other disasters. Hundreds of people die every year due to human stampedes occurring in religious festivals in India. Most of the crowded religious events involve simultaneous movement of very large groups of people in various directions. Sabarimala pilgrimage season which attracts lakhs of people from South India is one of the hotspots of human stampede due to various reasons. Various Departments of Government of Kerala work together in Sabarimala for the safe conduct of pilgrimage season. -

Infrastructure Module:Other Amenities and Services

Master Plan for Sabarimala Infrastructure Module:Other Amenities and Services MASTER PLAN MODULES INFRASTRUCTURE MODULE Other Amenities and Services 1. BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ...................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction and Relevance................................................................................................1 1.2 Aims and Objectives ............................................................................................................1 1.3 Methodology.........................................................................................................................1 1.4 Scope of the Study................................................................................................................2 1.5 Structure of the Report .......................................................................................................2 2. EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE AND PROJECTED DEMAND .....................................3 2.1 Health Care ..........................................................................................................................3 2.1.1 General Description ...................................................................................................................3 2.1.2 Infrastructure Available in the Region .......................................................................................4 2.1.3 Infrastructure Available at Sabarimala......................................................................................5 -

Fairs and Festivals of Kerala-Statements, Part VII B (Ii

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME VII KERALA PART VII B (ii) FAIRS AND FESTIVALS OF KERALA-STATEMENTS M. K. DEVASSY~ B. A., B. L. OF TbE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent ql Census Operations, KeTola and the Union Territory of Laccadive, Minicoy and Amindivi Islands PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS. DELHI-8 PRINTED AT THB C. M. S. PRESS. KOTfAYAM 1968 PRICE: Delux.e Rs. 20.00 or 46 sh. 8 d. or $ 7.20 cents Ordinary Rs.8.75 or 20 sh. 5 d. or $ 3.15 cents PREFACE It is one of the unique features of the 1961 Cell3us that a comprehensive survey was conducted about the fairs and festivals of the country. Apart from the fact that it is the first systematic attempt as far as Kerala is concerned, its particular value lay in presenting a record of these rapidly vanishing cultural heritage. The Census report on fairs and festivals consists of two publications, Part VII B (i), Fairs and Festivals of Kerala containing the descriptive portion and Part VII B (ii), Fairs and Festivals of Kerala-Statements giving the tables relating to the fairs and festivals. The first part has already been published in 1966. It is the second part that is presented in this book. This publication is entirely a compilation of the statements furnished by various agencies like the Departments of Health Services, Police, Local Bodies, Revenue and the Devaswom Boards of Travancore and Cochin. This is something like a directory of fairs and festivals in the State arranged according to di'>tricts and taluks, which might excite the curiosity of the scholars who are interested in investigating the religiou, centres and festivals.