The Experience of Village Enterprise Agent Model in Greater Masaka Area, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Annex C: Schedule for the In-Uganda Data Collection (Organisations & Persons Met With)

Annex C: Schedule for the In-Uganda Data Collection (Organisations & Persons Met With) Date & day Time Organisation/ Key Informant Friday 10.00 – 15.30 Team Planning Meeting 17/05/13 16.00 – 18.00 Straight Talk Foundation Executive Director, Ms Susan Ajok Saturday 09.00 – 17.00 Team Planning Meeting 18/05/13 Sunday 09.00 – 17.00 Team Planning Meeting 19/05/13 Monday 09.00 – 11.00 National Forum of People Living with HIV & AIDS 20/05/13 Networks in Uganda (NAFOPHANU) Executive Director, Ms Stella Kentutsi Finance Manager, Mr Geoffrey Twine Accountant, Mr Sentongo Steven Project Manager, Ms Peace Bahuma Uganda Young Positives Representative, Ms Jacqueline Alessie 15:00 – 16:30 The AIDS Support Organisation (TASO) Team-Leader Psychosocial Services, Mr Teddy Chimulwa Resource Mobilisation & Liaison Officer, Ms Sarah Khanakwa Bwayo Director Programmes, Dr Bernard Etukoit Programme Officer – Psychosocial, Ms Sophie Nanfume Team Leader Programmes, Mr Richard Wanyama Tuesday 08.00 – 17.00 Civil Society Fund Annual Review Meeting 21/05/13 Metropole Hotel 08:00 – 09:45 Uganda AIDS Commission Chair Partnership Committee, Dr Edward Katongole-Mbidde Wednesday 09:30 – 10:30 Embassy of Denmark 22/05/13 Counsellor Development, Ms Sanne Frost Helt Senior Programme Adviser – Health/HIV & AIDS, Mr Peter Ogwang Ogwal 10.00 Ambassador, H.E. Dan E Frederiksen 15:30 –17.00 Joint Donor Meeting Danida, Irish Aid and USAID Thursday 11:00 – 13:00 Technical Management Agent 23/05/13 Civil Society Fund Chief of Party, Mrs Sheila Marunga Coutinho Deputy Chief of Party, Dr Lillian Sekabembe M & E Adviser, Dr Denis Bwayo Chemonics International Inc. -

Are Our Children Learning? Annual Learning Assessment Report Uganda 2010

Are Our Children Learning? Annual Learning Assessment Report Uganda 2010 ANNU A L LE A RNING ASSESSMENT REPORT - UGANDA 2010 1 ii ANNU A L LE A RNING ASSESSMENT REPORT - UGANDA 2010 Are Our Children Learning? Annual Learning Assessment Report Uganda 2010 ANNU A L LE A RNING ASSESSMENT REPORT - UGANDA 2010 iii FOREWORD Over the last two decades, improving access to and quality of primary education has been the focus of Government, development partners and citizens in Uganda across East Africa. Significant investments have been made towards inputs in the areas of; curricula, teaching/learning processes, school inspection and support supervision, teachers’ accommodation, absenteeism, school facilities and infrastructure. These have paid off with an increase in enrollment figures over time. The challenge however that still stands is whether the millions of children in school for whom these investments have been made are learning. Uwezo, meaning “capability” in Kiswahili, is a four year initiative to improve competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged 6-16 years in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda through an innovative, civic-driven and public accountability approach to social change. Uwezo will enable policy makers as well as ordinary citizens – i.e. parents, students, local communities and public at large – to become aware of actual levels of children’s literacy and numeracy, and build on that awareness to stimulate practical and policy change across East Africa. In Uganda the initiative is hosted by the Uganda National NGO Forum. Uwezo involves a wide range of people – from local civil society organizations to ordinary citizens and local leaders. -

Gender, Tenure and Community Forests in Uganda

WORKING PAPER Gender, tenure and community forests in Uganda Abwoli Y. Banana Mohamed Bukenya Eusobio Arinaitwe Betty Birabwa Silvester Ssekindi Working Paper 87 Gender, tenure and community forests in Uganda Abwoli Y. Banana Mohamed Bukenya Eusobio Arinaitwe Betty Birabwa Silvester Ssekindi Working Paper 87 © 2012 Center for International Forestry Research All rights reserved Banana, A. Y., Bukenya, M., Arinaitwe, E., Birabwa, B. and Ssekindi, S. 2012 Gender, tenure and community forests in Uganda. Working Paper 87. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia. Cover photo by Neil Palmer/CIAT Faces of southwestern Uganda CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] www.cifor.org Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the authors’ institutions or the financial sponsors of this publication. Table of contents Abbreviations v Acknowledgements vi Executive summary vii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Management of forestry resources in Uganda 1 1.2 The role of women in forest management in Uganda 1 1.3 Factors that influence participation of women in sustainable forest management 2 2 Description of the study and extent of involvement of external actors 4 2.1 Description of study area 4 2.2 Criteria for selecting study districts and sites 5 3 Methodology 6 3.1 Assessing the extent to which gender features in projects and programmes 6 3.2 Assessing the extent to which gender features in forest use and management in forest-adjacent -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. Nabajjuzi Wetland System Ramsar Information Sheet 1. Name and address of the RIS compiler: Achilles Byaruhanga and Stephen Kigoolo NatureUganda Plot 83 Tufnel Drive, Kamwokya, P. O Box 27034, Kampala, Uganda. Tel: 256 41 540719 Fax no: 256 41 533 528 E-mail: [email protected] 2. Date: 20 September 2005. 3. Country: The Republic of Uganda 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Nabajjuzi Wetland System 5. Map of the Ramsar Site: Hard copy: attached Digital (electronic) format: yes 6. Geographical coordinates: 31o33’ – 31o49” E and 00o27” S – 00o05” N. 7. General Location: Nabajjuzi wetland system lies south west of central Uganda in Masaka district (Lwabenge, Kyamulibwa, Kalungu, Mukungwe, Nyendo, Kimanya, Katwe, Kingo, Kibinge, Butenga and Bigasa sub-counties), Sembabule district (Mijwala sub-county) and Mpigi district (Kabulasoke sub-county). It stretches up to the Kagera River basin area to the north and past the periphery of Masaka Town Municipal Council along Masaka – Mbarara highway to the south. 8. -

Vol. XCV1 No. 1 3Rd January, 2003 Price: Shs

The 1 no *J rt at K*<« uiAxiiK Published by ^Uganda Gazette Authority Vol. XCV1 No. 1 3rd January, 2003 Price: Shs. 1000 CONTENTS Page General Notice No. 3 of 2003. The Uganda NationalExaminations Board—Notice 1 THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION ACT, 1997. The Electoral Commission—Notices ............. 1-2 Act No. 3 of 1997. Advertisements ....................................................... 2 Section 30. General Notice No. 1 of 2003. NOTICE. THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS ACT, 2001. APPOINTMENT OF RETURNING OFFICER FOR MUKONO ELECTORAL DISTRICT. Section 5(4). In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Electoral NOTICE OP COMPLETION OF FORMAL EDUCATION Commission by section 30(1) of the Electoral Commission OF ADVANCED LEVEL STANDARD EQUIVALENT Act, No. 3 of 1997, Mr Charles Willy Ochola. Returning Notice is hereby given that by virtue of the powers Officer, Bushenyi Electoral District has been appointed conferred upon the Uganda National Examinations Board Returning Officer. Mukono Electoral District and degazetted under section 5(4) of the Parliamentary Elections Act, 2001. Returning Officer, Bushenyi Electoral District. JOSEPH K. WASSWA By this Notice the persons in the Schedule to this Notice are is said to have completed formal education of Advanced hereby degazetted Assistant Returning Officer and Returning level standard. Officers of the respective Electoral Districts. Issued at Kampala this 24th day of December, 2002. SCHEDULE. DAN N. ODONGO, 1. Mr. Mudoi Isaac Returning Officer. Mubcnde for Acting Secretary. 2. Mr. Biretwa J.A Returning Officer. Mpigi Uganda National Examinations Hoard. 3. Mr. Nyendc Juma Returning Officer. Bugiri 4. Mrs. Marion Tukahurirwa Returning Officer, Wakiso 5. Mr. Kisense Sam Returning Officer, Mukono; and General Notice No. -

The Haddon Matrix, Amechanism for Examining Severe Car Accidents on Masaka Road in Central Uganda

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 10 (2018) pp.: 42-50 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper The Haddon Matrix, Amechanism For Examining Severe Car Accidents On Masaka Road In Central Uganda. Nabukeera Madinah* Lecturer Kyambogo University Faculty of Arts and Social Science Department of History and Political Science ABSTRACT :The aim of the study was to use the Haddon matrix to investigate accident crashes on Masaka road and the causes of the many severe car crashes, to examine if a safety belt would have reduced injuries. A face to face in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with five male truck drivers who survived accidents while driving and still served as truck drivers on Masaka Road. The sample was identified with purposive and snowball sampling techniques. Ethical considerations were observed during data collection through bracketing and transcription.A phenomenological analysis (PA) was employed to each participant’s discernment of the specific and general accounts of the causes of accidents on the same road to enable the generation of themes that make “sense” of their lived worlds as truck drivers and accident involvement. Interesting themes enlightening accidents emerged out of the data: human error, police, UNRA1, technical errors, environmental factors and socio-cultural context affect the typical routines. As a result, a lot has been accomplished such as vehicle inspection centers, controls put in place, physical works have been suggested, round table discussion among stake holders. In addition, substantial call for change of behavior as means to reduce accidents has been made.Considering the study results, the above mentioned causes and more together leave truck drivers in accident involvement inescapable. -

2020 List of Chief Administrative Officers in Uganda.Pdf

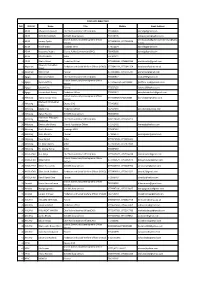

CONTACTS DIRECTORY NO District Name Title Mobile Email Address 2 ABIM Ofwono Emmanuel Chief Administrative Officer(CAO) 772446803 [email protected] 3 ABIM OCHERO ALIDOUS OVCMIS focal person 772975445 [email protected] District Community Development Officer [email protected]/lammyo@yaho 4 ABIM Lammy Oyollo 0772858609 , 0757118504 (DCDO) o.com 5 ABIM Akech Grace In charge CFPU 774551194 [email protected] 6 ABIM Katuramu Robert District Police Commander (DPC) 781405168 [email protected] 7 ABIM OYUGI DAVID Other 786101311 8 ABIM Okello Alfred Probation Officer 0774451446 , 0784419765 [email protected] Mawadri Ramadhan 9 Adjumani Probation and Social Welfare Officer (PSWO) 0772841354 , 0772841354 [email protected] Drami 10 Adjumani Moini Fred Planner 0772370866 , 0791755787 [email protected] 11 Agago Mulondo Robert Chief Administrative Officer(CAO) 774383827 [email protected] District Community Development Officer 12 Agago Ojok Geoffrey 0773436511/0758491898 [email protected] (DCDO) 13 Agago Lakony Lino Planner 772527150 [email protected] 14 Agago Lakomekech Nancy Probation Officer 774383827 [email protected] District Community Development Officer 15 Alebtong Auma Dorcas Vicky 0773535685/0751535685 [email protected] (DCDO) Oketayot Christopher 16 Alebtong Deputy CAO 772461866 James 17 Alebtong Okabo Pius Probation Officer 782561639 [email protected] 18 Alebtong Ogwal Paulino OVCMIS focal person 783933703 Abdulnoor Mbaagwa 19 Alebtong Chief Administrative Officer(CAO) 0392178347 , 0772663215 Muwonge 20 Alebtong Owera John Bosco District Population Officer 772751402 [email protected] 21 Alebtong Akullo Beatrice In charge CFPU 771687426 22 Alebtong Ocan Morrish Planner 774006073 [email protected] 23 Alebtong Kissa Denish Other 0772673509 , 0772331941 24 Alebtong Dr. Noki Charles Other 0772673509 , 0772673509 25 Alebtong Dr. -

The Soils and Land/Use of , Buganda

The soils and land/use of , Buganda f Dy L S.A.Radwanski F, L1960 ,J "f ISRIC LIBRARY KE - 1960.03 Hageningen The Setherlands 'Vflgcnlngen, The Netherléfnds ii Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use' Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact soil.isrictawur.nl indicating the item reference number concerned. KSS Library 631.47 U G A N' D A P R O T E C T O R A T Ê DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE MEMOIRS OF THE RESEARCH DIViSJOM SERIES I: SOILS Number 4 A Reconnaissance Survey S. A. Radv/anskî M.A. {Cantab.) W UGANDA PROTECTORAT DEPARTMENT OP AGRICULTURE MEMOIRS OF THE RESEARCH DIVISION SERIES 1 - SOILS Number 4 THE SOILS AND LAND-USE OF BUGANDA A Reconnaissance Survey by ià. A. Radwanski, M.A. (Cantab.) Kawanda Research Station P.O. Box 265 Kampala 1st March i960 COOTEtTTS ••'•' ,.:...-.::..:•... Page ' General Introduction -.. -..-.. '. .. 1 Climate v. .. ;. *.. ,. ".-. 2 Vegetation- .. ;. '.. ',. 'V. ".. 6 Geology '..-.. 9 Geomorphology ' .. ••'. •;1--»-i--'•'•-.-.-•"-;". "";.'" V. .. .... .. 12 Soils (introductory account) .. '.'. .... .. .. .. 20 Soil-Mat>T>ing Units Introduction .. .. , .. .. 23 Kas oio Catena .. :ii- -••.-.•--•• •.•;" ., 32 Koki-Catena' .". .'. .*. .. .. ?. 33 Tolefo Series ; ; .. ". ". '. .... .. .. ....... 37 Bugânda Catena . w . : ,. ... 37; Kyebe Catena .. .. .. .. .. ....:..-.. :.,. .. .. 4.2 Bowà'"Catena . ; .. .. .. .. .. 43 'd~ Kabira, Mirambi and Mawogola Catenas .. ... .. .;••<.• '.44 • Makole Series ... ... .. "50 Mityana Catena ., . -

The Political Economy of Violence in Uganda's Masaka

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 11 (2018) pp.: 01-18 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Insecurty In Maska District –Publication Astate Of Insecurity(delete): The Political Economy Of Violence In Uganda’s Masaka District Nabukeera Madinah (Phd) Senior Lecturer Islamic University in Uganda Females’ CampusFaculty of Management Studies Department of Public Administration ABSTRACT:This article examines the problem of insecurity in Uganda in areas of Masaka district in the western part of the country. It provides a typology of the insecurity incidents which occurred in areas of Bukomansimbi, Lwengo, Rakai, Sembabule, Kalungu, Nyendo, Lyantonde districts and Kingo sub-county and examines the steps which government and other stakeholders have taken to address the problem. Using a qualitative approach, interviews were conducted in the affected areas with LCI chairpersons, locals and area members of parliament together with library research to explain why these measures have failed to reduce the high level of crime that takes place in and around the country. The article focuses on three related issues: the political economy of the Uganda state;catalysts for insecurity and the manner in which the government and other actors have sought to manage the country's insecurity situation. Received 17 October, 2018; Accepted 03 Novenber, 2018 © The author(s) 2018. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. OVER VIEW Colonial Economy The mid-19th Century was a period of Scramble and Partition of Africa. Whether African societies resisted or collaborated, by 1914 the whole of African continent had been put under colonial administration with exception of Ethiopia and Liberia. -

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement .................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context ....................................................................... 7 2.1 Summary Statistics, Disease Burden and Country Profile ................................................. 7 2.2 Investment Profile ............................................................................................................................. 19 2.3 National Sustainability Profile Update .............................................................................................. 24 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR Investments Geographically to Disease Burden ............................................ 28 2.5 Stakeholder Engagement .................................................................................................................. 29 3.0 Geographic and Population Prioritization ...................................................................... 32 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-Up Locations and Populations .. 33 4.1 Finding the missing, getting them on treatment, and retaining them ensuring viral suppression .. 34 4.2 Prevention, specifically detailing programs for priority programming: ........................................... 52 4.2.a. OVC and Child-Focused COP19 Interventions ..........................................................................