TIST UG PD-VCS-Ex 20 Dist Enviro Profile Kabale.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gorilla Adventure in Uganda 2021

The Gorilla Adventure in Uganda 2021 Join us for a once in a lifetime trek in ‘The Impenetrable Forest’ of Bwindi and see Uganda’s mountain gorilla in their natural habitat. 29 September - 8 October 2021 For more information and to register online: www.dream-challenges.com 01590 646410 or email: [email protected] The Gorilla Adventure in Uganda 2021 Trek through the rainforests of the Virunga Mountain Range and encounter endangered species on this once-in-a-lifetime gorilla tracking adventure. Together, we’ll climb the awesome Mount Sabinyo, with panoramas across three different countries: Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo! Then we’ll trek through valleys, lush vegetation and local communities, with chances to see golden monkeys and elephants. After a breath-taking boat ride across the volcanic Lake Mutanda in wooden canoes, it’s time to go ape! We venture into Bwindi Impenetrable Forest to track the amazing Nkuringo Gorilla Family Group! Encountering these magnificent and sadly, critically endangered, animals in their natural habitat is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that few will ever get to experience. Left with an unforgettable sense of awe, we end our adventure by getting involved with a variety of eco activities for the local community at the Singing Gorilla Project. Giving back to the planet We’re dedicated to practising responsible tourism and we’ve designed this amazing itinerary especially to give back to the places we visit. We have picked fantastic suppliers local to the area; plus we get involved with local eco work at Singing Gorilla Projects in Nkuringo. -

"A Revision of the Freshwater Crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa."

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons Journal Articles FacWorks 2011 "A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa." Neil Cumberlidge Northern Michigan University Kirstin S. Meyer Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cumberlidge, Neil and Meyer, Kirstin S., " "A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa." " (2011). Journal Articles. 30. https://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles/30 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the FacWorks at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. This article was downloaded by: [Cumberlidge, Neil] On: 16 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 938476138] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Natural History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713192031 The freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamonautidae) Neil Cumberlidgea; Kirstin S. Meyera a Department of Biology, Northern Michigan University, Marquette, Michigan, USA Online publication date: 08 June 2011 To cite this Article Cumberlidge, Neil and Meyer, Kirstin S.(2011) 'The freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamonautidae)', Journal of Natural History, 45: 29, 1835 — 1857 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2011.562618 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2011.562618 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

Departm~N • for The

Annual Report of the Game Department for the year ended 31st December, 1935 Item Type monograph Publisher Game Department, Uganda Protectorate Download date 23/09/2021 21:05:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35596 .. UqANDA PROTECTO ATE. I ANNUAL REPO T o THE • GAME DEPARTM~N • FOR THE . Year ended 31st December, 1935. I· ~nhli£heb hll ®ommanb of ll.li£ Ot.n:ellcncrr the Q301mnor. ENTEBBE: PRINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER,. UGANDA• 1936 { .-r ~... .. , LIST OF CONTENTS. SECTION I.-ADMINISTRATION. PAGK. StaJr 3 Financial-Expenditure and Revenue 3 FOR THE DJegal Ki)ling of Game and Breaches of .Bame La"'s ... 5 Game Ordinance, 1926 5 Game Reserves. ... ... ... ... ... 5 Game Trophies, 'including Table of ,,·eight. of "hcence" ivory i SECTION Il.-ELEPHANT CO~TROL. Game Warden Game Ranger8 General Remarks 8 Return of Elephant. Destroyed ... ... •.. 8 Table d Control Ivory. based on tUok weight; and Notes 9 Clerk ... .•. J Table "(11 ,"'onnd Ivory from Uncon[,rolled are:>. ' .. 9 Tabld\'ot Faun.!! Ivory from Controlled sreas; and Notes - 9 Distritt Oont~t ... 10 1. Figures for-I General No~ r-Fatalities 18 Expenditure Elephant Speared 19 Visit to lYlasindi 'Township 19 Revenue Sex R.atio ... 19 Balanc'e 0" Curio,us Injury due to Fighting 19 Elephant Swimming 19 Nalive Tales 20 The revenue was Ri!!es ' 20 t(a) Sale of (b) Sale (c) Gam SECTION IlL-NOTES ON THE FAUNA. Receipts frolIl f\., (A) M'M~I'LS- (i) Primates 21 1934 figures; and from (il) Oarnivora 22 (iii) Ungulates 25 2; The result (8) BIRDS 30 November were quite (0) REPI'ILES 34 mately Shs. -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

MGAHINGA GORILLA NATIONAL PARK Lives on the Virungas and Half in Nearby Bwindi Hotel/Lodge 1 Boundary Trail Impenetrable NP

half of the total population (780) of this endangered ape MGAHINGA GORILLA NATIONAL PARK lives on the Virungas and half in nearby Bwindi Hotel/lodge 1 Boundary Trail Impenetrable NP. The bamboo zone in Mgahinga is also gazetted the portion of the range in present day Congo home to another endangered primate, the golden PARK AT A GLANCE and Rwanda as a national park to protect mountain 2 Border Trail monkey which occurs only in the bamboo forests of the Volcano climbing Uganda’s smallest park (33.7km²) protects mountain gorillas. The British administration declared the Virungas. Other large mammals include elephant, gorillas and other fauna on the Ugandan slopes of the 3 Sabinyo Gorge buffalo, leopard and giant forest hog though these are Virunga volcanoes. Culture/history rarely encountered in the dense forest. 4 Sabinyo Climb Though small in size, Mgahinga contains a dramatic, Primate tracking Though the park’s birdlist currently stands at just 115 panoramic backdrop formed by three volcanoes 5 Batwa Trail species, this includes many localized forest birds and Albertine Rift endemics, including the striking Rwenzori Mgahinga has one habituated gorilla group. Scenic highlight 6 Mgahinga Climb turaco. Mgahinga Gorilla National Park covers the slopes of Birding highlight 7 Muhuvura Climb LOCAL PEOPLE Historically, the forests of Mgahinga were home to Batwa Pygmies whose hunter-gatherer lifestyle predates all other human activities in the region. In recent centuries, the area has been cleared and settled by Bafumbira farmers who cultivate up to the edge of the remnant forest protected within the national park. ACCESS Roads Mgahinga Gorilla National Park is 524km from Kampala. -

Speech to Parliament by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of The

Speech to Parliament By H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda Parliamentary Buildings - 13th December, 2012 1 Rt. Hon. Speaker, I have decided to use the rights of the President, under Article 101 (2) of the 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, to address Parliament. I am exercising this right in order to counter the nefarious and mendacious campaign of the foreign interests, using NGOs and some Members of Parliament, to try and cripple or disorient the development of the Oil sector. If the Ugandans may remember, this is not the first time these interests try to distort the development of our history. When we were fighting the Sudanese-sponsored terrorism of Kony or when we were fighting the armed cattle- rustlers in Karamoja, you remember, there were groups, including some religious leaders, Opposition Members of Parliament as well as NGOs, which would spend all the 2 time denouncing us, the Freedom Fighters. They were denouncing those who were fighting to defend the lives and properties of the people, rather than denouncing the terrorists, the cattle-rustlers and their external-backers (in the case of Kony) as well as their internal collaborators. It would appear as if the wrong-doer was the Government, the NRM, rather than the criminals. We, patiently, put up with that malignment at the same time as we fought, got injured or killed, against the enemy until we achieved victory. Eventually, we won, supported by the ordinary people and the different people’s militias. There is total peace in the whole country and yet the misleaders of those years have not apologized to the Ugandans for their mendacity. -

Vulnerable and Marginalized Groups Framework (Vmgf)

VULNERABLE AND MARGINALIZED GROUPS FRAMEWORK (VMGF) FOR THE UGANDA DIGITAL ACCELERATION PROGRAM [UDAP] FPIC with The Tepeth Community in Tapac FPIC with the Batwa Community in Bundibugyo MARCH 2021 Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK Action Parties Designation Signature Prepared Chris OPESEN & Derrick Social Scientist & Environmental KYATEREKERA Specialist Reviewed Flavia OPIO Business Analyst Approved Vivian DDAMBYA Director Technical Services DOCUMENT NUMBER: NITA-U/2021/PLN THE NATIONAL INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY, UGANDA (NITA-U) Palm Courts; Plot 7A Rotary Avenue (Former Lugogo Bypass). P.O. Box 33151, Kampala- Uganda Tel: +256-417-801041/2, Fax: +256-417-801050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nita.go.ug The Uganda Digital Acceleration Program [UDAP) Page iii Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS........................................................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Background................................................................................................................................................. -

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

Land Use Change and Soil Degradation in the Southwestern Highlands of Uganda

LAND USE CHANGE AND SOIL DEGRADATION IN THE SOUTHWESTERN HIGHLANDS OF UGANDA Simon Bolwig A Contribution to the Strategic Criteria for Rural Investments in Productivity (SCRIP) Program of the USAID Uganda Mission The International Food Policy Research Institute 2033 K Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 September 2002 Strategic Criteria for Rural Investments in Productivity (SCRIP) is a USAID-funded program in Uganda implemented by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in collaboration with Makerere University Faculty of Agriculture and Institute for Environment and Natural Resources. The key objective is to provide spatially-explicit strategic assessments of sustainable rural livelihood and land use options for Uganda, taking account of geographical and household factors such as asset endowments, human capacity, institutions, infrastructure, technology, markets & trade, and natural resources (ecosystem goods and services). It is the hope that this information will help improve the quality of policies and investment programs for the sustainable development of rural areas in Uganda. SCRIP builds in part on the IFPRI project Policies for Improved Land Management in Uganda (1999-2002). SCRIP started in March 2001 and is scheduled to run until 2006. The origin of SCRIP lies in a challenge that the USAID Uganda Mission set itself in designing a new strategic objective (SO) targeted at increasing rural incomes. The Expanded Sustainable Economic Opportunities for Rural Sector Growth strategic objective will be implemented over the period 2002-2007. This new SO is a combination of previously separate strategies and country programs on enhancing agricultural productivity, market and trade development, and improved environmental management. Contact in Kampala Contact in Washington, D.C. -

Kabale District HRV Profile.Pdf

Kabale District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 KABALE DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgement On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparednes Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred- Early Warning system Database programmer. My appreciation also goes to Kabale District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees KABALE DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment was a combination of spatial modeling using socio-ecological spatial layers (i.e. DEM, Slope, Aspect, Flow Accumulation, Land use, vegetation cover, hydrology, soil types and soil moisture content, population, socio-economic, health facilities, accessibility, and meteorological data) and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

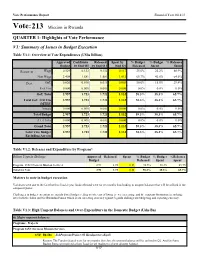

Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:213 Mission in Rwanda QUARTER 1: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q1 by End Q 1 End Q1 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 0.529 0.132 0.132 0.117 25.0% 22.2% 88.9% Non Wage 2.408 1.581 1.581 1.012 65.7% 42.0% 64.0% Devt. GoU 0.020 0.010 0.010 0.003 50.0% 15.0% 29.4% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total GoU+Ext Fin 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% (MTEF) Arrears 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total Vote Budget 2.957 1.723 1.723 1.132 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1652 Overseas Mission Services 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Total for Vote 2.96 1.72 1.13 58.3% 38.3% 65.7% Matters to note in budget execution Variances were due to the fact that this finacial year funds released were for six months thus leading to unspent balances that will be utilised in the subquent Quater.