Impact of Three Microfinance Programs in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resume: NKUGWA FRED

Resume: NKUGWA FRED Personal Information Application Title IT Professional First Name NKUGWA Middle Name N/A Last Name FRED Email Address [email protected] Cell 0700470333 Nationality Uganda Gender Male Category Computer/ IT Sub Category Computer Installations Services Job Type Full-Time Highest Education University Total Experience 1 Year Date of Birth 23-02-1996 Work Phone 0778728752 Home Phone 0700470333 Date you can start 01-01-1970 Driving License Yes License No. Searchable Yes I am Available Yes Address Address Address Kimaanya Masaka City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Institutes Institute Uganda Martyrs University City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Address Nkozi village- Kayabwe Kampala road Certificate Name Bachelor of Science in Information Technology Study Area Information Technology Employers Employer Employer Hirt IT Solutions Position Web developer Responsibilities Web design and programming ,computer repair, installation and trouble shooting ,database designing. Pay Upon Leaving N/A Supervisor Fr. Emmanuel From Date 18-06-2019 To Date 18-06-2021 Leave Reason Iam still working with the company City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Phone +256783494405 Address Kilumba-Masaka Employer Employer Masaka Regional Referral Hospital Position Data Clerk Responsibilities • Database design and development • Hardware and Software Installation. • Data backup • Server room management • Network configuration. • Files and folder sharing. • Troubleshooting computers. • Website design and development Pay Upon Leaving N/A Supervisor Mr.Ssemakadde Mathew From Date 01-05-2019 To Date 01-08-2019 Leave Reason Industrial training period ended City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Phone +256701717271 Address Masaka Uganda Skills Skills • Information security skills with a certificate from IBM skills academy USA. -

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

Absa Bank 22

Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 2020 Promoting Partnerships Transforming Banking Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 3 Content About Uganda 6 Bankers' Association UBA Structure and 9 Governance UBA Member 10 Bank CEOs 15 UBA Executive Committee 2020 16 UBA Secretariat Management Team UBA Committee 17 Representatives 2020 Content Message from the 20 UBA Chairman Message from the 40 Executive Director UBA Activities 42 2020 CSR & UBA Member 62 Bank Activities Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 70 December 2020 5 About Uganda Bankers' Association Commercial 25 banks Development 02 Banks Tier 2 & 3 Financial 09 Institutions ganda Bankers’ Association (UBA) is a membership based organization for financial institutions licensed and supervised by Bank of Uganda. Established in 1981, UBA is currently made up of 25 commercial banks, 2 development Banks (Uganda Development Bank and East African Development Bank) and 9 Tier 2 & Tier 3 Financial Institutions (FINCA, Pride Microfinance Limited, Post Bank, Top Finance , Yako Microfinance, UGAFODE, UEFC, Brac Uganda Bank and Mercantile Credit Bank). 6 • Promote and represent the interests of the The UBA’s member banks, • Develop and maintain a code of ethics and best banking practices among its mandate membership. • Encourage & undertake high quality policy is to; development initiatives and research on the banking sector, including trends, key issues & drivers impacting on or influencing the industry and national development processes therein through partnerships in banking & finance, in collaboration with other agencies (local, regional, international including academia) and research networks to generate new and original policy insights. • Develop and deliver advocacy strategies to influence relevant stakeholders and achieve policy changes at industry and national level. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized RP1030 v1 KAWANDA – MASAKA TRANSMISSION LINE Project Name: ELECTRICITY SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Number: P119737 Report for: RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) PREPARATION, REVIEW AND AUTHORISATION Revision # Date Prepared by Reviewed by Approved for Issue by ISSUE REGISTER Distribution List Date Issued Number of Copies : April 2011 SMEC staff: Associates: Office Library (SMEC office location): SMEC Project File: SMEC COMPANY DETAILS Tel: Fax: Email: www.smec.com Review and Update Kawanda Masaka 220kV, 137km T Line 5116008 | June 13, 2011 Page | i We certify that this Resettlement Action Plan was conducted under our direct supervision and based on the Terms of Reference provided to us by Uganda Electricity Transmission Company Ltd. We hereby certify that the particulars given in this report are correct and true to the best of our knowledge. Table 1: RAP Review Team Resource Designation Signature Social-Economist/RAP M/s Elizabeth Aisu Specialist/Team leader Mr. Orena John Charles Registered Surveyor Mr. Ssali Nicholas Registered Valuer Mr. Yorokamu Nuwahambasa Sociologist Mr. Lyadda Nathan Social Worker M/s Julliet Musanyana Social Worker ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SMEC International wishes to express their gratitude to The Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) team, AFRICAN TECHNOLOGIES (U) Ltd and to all the persons who were consulted for their useful contributions that made the assessment successful. In this regard, Mr. Ian Kyeyune , LC5 Chairman Wakiso, M/s Joan Kironde, the then District Environment Officer Wakiso, M/s. Muniya Fiona, Sector Manager Mpigi, and to all the Local Council Leaders in all the affected Districts and the PAPs M/s Ziria Tibalwa Principal Planning Officer, Mr. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( E Nzara Il ILEMI TRIANGLE N N

!( !( !( )"" !( ! Omo AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( e Nzara il ILEMI TRIANGLE N n Banzali Asa Yambio i ! ! !( a t n u ETHIOPIA o !( !( SNNP M Camp 15 WESTERN ( l !( EQUATORIA e !( b e Torit Keyala Lobira Digba J !( !( Nadapal ! l !( ± e r Lainya h a ! !Yakuluku !( Diagbe B Malingindu Bangoie ! !( ! Duru EASTERN ! Chukudum Lokitaung EQUATORIA !( Napopo Ukwa Lokichokio ! ! !( Banda ! Kpelememe SOUTH SUDAN ! Bili Bangadi ! ! Magwi Yei !( Tikadzi ! CENTRAL Ikotos EQUATORIA !( Ango !( Bwendi !( Moli Dakwa ! ! ! Nambili Epi ! ! ! Kumbo Longo !( !Mangombo !Ngilima ! Kajo Keji Magombo !( Kurukwata ! Manzi ! ! Aba Lake Roa !( ! Wando Turkana Uda ! ! Bendele Manziga ! ! ! Djabir Kakuma Apoka !( !( Uele !( MARSABIT Faradje Niangara Gangara Morobo Kapedo !( ! !( !( Dikumba Dramba ! Dingila Bambili Guma ! Moyo !( !( ! Ali !( Dungu ! Wando ! Mokombo Gata Okondo ! ! ! !( Nimule !( Madi-Opel Bandia Amadi !( ! ! Makilimbo Denge Karenga ! ! Laropi !( !( !( LEGEND Mbuma Malengoya Ndoa !( Kalokol ! ! Angodia Mangada ! Duku ile Nimule Kaabong !( ! ! ! ! Kaya N Dembia ert !( Po Kumuka Alb Padibe ! Gubeli ! Tadu Yumbe !( Bambesa ! Wauwa Bumva !( !( Locations Bima !( ! Tapili ! Monietu ! !( ! Dili Lodonga " ! Koboko " Capital city Dingba Bibi Adi !( !( Orom ) ! Midi-midi ! ! !( Bima Ganga Likandi Digili ! Adjumani ! ! ! ! Gabu Todro Namokora Loyoro TURKANA Major city ! Tora Nzoro ! !( !( ! ! !( Lagbo Oleba Kitgum Other city Mabangana Tibo Wamba-moke Okodongwe ! Oria !( !( ! ! ! ! ! Omugo Kitgum-Matidi Kana Omiya Anyima !( ! !( Atiak Agameto Makongo -

Olweny Key Note.Pdf

Third RUFORUM Biennial Meeting 24 - 28 September 2012, Entebbe, Uganda Research Application Summary Providing opportunities to African youths and other disadvantaged groups: The Uganda Martyrs University approach/ strategy Olweny, C.L.M. MD, FRACP Uganda Martyrs University, P. O. Box 5498, Kampala, Uganda Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Youth is a period of building “self concept” often influenced by parents, peers, gender and culture. The United Nations (UN) youth agenda is guided by the World Programme of Action for Youths (WPAY) adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1995. WPAY has 15 priority areas. Africa is often regarded as the “youngest continent” because of the large number of young persons, and in Uganda, 49% of the population is under 15 years. Uganda Martyrs University (UMU) is a faith-based, private, not-for-profit institution founded in 1993 to address the perceived moral decay in business and professions. At UMU, ethics is a compulsory subject irrespective of one’s field of study. UMU obtained its civil charter in April 2005 and is one of only six out of 29 private universities in Uganda with this status. UMU places research and scholarship on top of its role agenda, followed by community engagement and finally teaching. UMU is located in a rural setting, and believes a university must not exist in isolation and that a university must be owned by the community where it is located. UMU’s focus areas include, inter-alia, HIV/AIDS, poverty alleviation, peace and justice and food security. UMU’s outreach project at Nnindye is to help the community lift itself out of poverty and all faculties are strongly encouraged to mainstream outreach in their curricula. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, and the International Business Commons Recommended Citation Cowans, Aaron, "Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1226. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1226 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Uganda: Microfinance and Entrepreneurship Academic Advisor: Godfrey Byekwaso Academic Director: Martha Wandera Fall 2011 Dedication This work is dedicated to my family in America and the amazing people I have met here in Uganda, who have all helped me throughout my journey. 2 Acknowledgements While so many people helped me along my way, I want to acknowledge the following people in particular who were instrumental to my experience here. Martha Wandera, Helen Lwemamu and the rest of the SIT staff for putting together such a fantastic program. I have learned so much here and made memories which will last a lifetime. This was all possible because of your constant hard work and dedication. All of the staff at FINCA Uganda and FINCA International who so graciously hosted me as an intern and supported me through the duration of my internship. -

Population by Parish

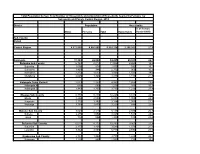

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Draft Outline

COMMUNICATION FOR HEALTHY COMMUNITIES (CHC) YEAR SEVEN Quarter One Report October 1st, 2019 to December 31st, 2019 Submission Date: 31st January 2020 Agreement Number: AID-617-A-13-00003 Activity Start Date and End Date: June 21st, 2013 to June 20th, 2020 AOR Name: Kathleen Frank Submitted by: Sheila Marunga Coutinho, Chief of Party Communication for Healthy Communities Plot 15 Kitante Close, Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256-312-266-406 Email: [email protected] Submitted to: Agreement Officer’s Representative (AOR) Copied to: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Uganda Mission (USAID/Uganda). 1 ACTIVITY INFORMATION Activity Name: Communication for Healthy Communities (CHC) Project Communication for Healthy Communities (CHC) Activity Start Date and End Date 21st June 2013 to 20th June 2020 Name of Prime Implementing FHI360 Partner Agreement Number: AID-617-A-13-00003 Name of Subcontractors/Sub- None awardees and Dollar Amounts: Major Counterpart Organizations: The Government of Uganda and USG Implementing Partners Geographic Coverage National Reporting Period: 1st October 2019 to 31st December 2019 i ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavior Change Communication CHC Communication for Healthy Communities CLA Collaboration, Learning, and Adaptation CPR Contraceptive Prevalence Rate DHE District Health Educator DHMT District Health Management Committee DHO District Health Officer DHT District Health Team DQA Data Quality Assessment